Published online Aug 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i32.4342

Revised: July 23, 2012

Accepted: July 28, 2012

Published online: August 28, 2012

AIM: To investigate national trends in distal pancreatectomy (DP) through query of three national patient care databases.

METHODS: From the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS, 2003-2009), the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP, 2005-2010), and the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER, 2003-2009) databases using appropriate diagnostic and procedural codes we identified all patients with a diagnosis of a benign or malignant lesion of the body and/or tail of the pancreas that had undergone a partial or distal pancreatectomy. Utilization of laparoscopy was defined in NIS by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision correspondent procedure code; and in NSQIP by the exploratory laparoscopy or unlisted procedure current procedural terminology codes. In SEER, patients were identified by the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition diagnosis codes and the SEER Program Code Manual, third edition procedure codes. We analyzed the databases with respect to trends of inpatient outcome metrics, oncologic outcomes, and hospital volumes in patients with lesions of the neck and body of the pancreas that underwent operative resection.

RESULTS: NIS, NSQIP and SEER identified 4242, 2681 and 11 082 DP resections, respectively. Overall, laparoscopy was utilized in 15% (NIS) and 27% (NSQIP). No significant increase was seen over the course of the study. Resection was performed for malignancy in 59% (NIS) and 66% (NSQIP). Neither patient Body mass index nor comorbidities were associated with operative approach (P = 0.95 and P = 0.96, respectively). Mortality (3% vs 2%, P = 0.05) and reoperation (4% vs 4%, P = 1.0) was not different between laparoscopy and open groups. Overall complications (10% vs 15%, P < 0.001), hospital costs [44 741 dollars, interquartile range (IQR) 28 347-74 114 dollars vs 49 792 dollars, IQR 13 299-73 463, P = 0.02] and hospital length of stay (7 d, IQR 4-11 d vs 7 d, IQR 6-10, P < 0.001) were less when laparoscopy was utilized. One and two year survival after resection for malignancy were unchanged over the course of the study (ductal adenocarinoma 1-year 63.6% and 2-year 35.1%, P = 0.53; intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm and nueroendocrine 1-year 90% and 2-year 84%, P = 0.25). The majority of resections were performed in teaching hospitals (77% NIS and 85% NSQIP), but minimally invasive surgery (MIS) was not more likely to be used in teaching hospitals (15% vs 14%, P = 0.26). Hospitals in the top decile for volume were more likely to be teaching hospitals than lower volume deciles (88% vs 43%, P < 0.001), but were no more likely to utilize MIS at resection. Complication rate in teaching and the top decile hospitals was not significantly decreased when compared to non-teaching (15% vs 14%, P = 0.72) and lower volume hospitals (14% vs 15%, P = 0.99). No difference was seen in the median number of lymph nodes and lymph node ratio in N1 disease when compared by year (P = 0.17 and P = 0.96, respectively).

CONCLUSION: There appears to be an overall underutilization of laparoscopy for DP. Centralization does not appear to be occurring. Survival and lymph node harvest have not changed.

- Citation: Rosales-Velderrain A, Bowers SP, Goldberg RF, Clarke TM, Buchanan MA, Stauffer JA, Asbun HJ. National trends in resection of the distal pancreas. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(32): 4342-4349

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i32/4342.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i32.4342

The first open distal pancreatectomy was reported by Billroth in 1884[1,2]. In the early 1900s, Finney[1] and Mayo[3] reported the first open case series and description of their respective techniques. The laparoscopic approach was first introduced to general surgery in the 1980s for gallbladder resection, and quickly adopted as an operative approach for resection of other solid organs. This adoption of laparoscopy has been slower in pancreatic surgery due to the complexity of the procedure, low number of cases, the level of technical skills required by the surgeon in manipulating the important vascular structures, and the lower acceptance of this approach in the resection of malignant lesions.

The use of laparoscopy in distal pancreatectomy was first described in a porcine model by Soper et al[4] in 1994. Soon after this reports of laparoscopy in human patients were reported[5], though for many years laparoscopy was used principally for staging of malignancy. Multiple reports have shown that laparoscopic pancreatic resection is safe and feasible for benign and malignant pancreas lesions[6-9]. The known benefits of laparoscopic approach such as lower intraoperative blood loss, less pain and analgesic requirements, earlier return of bowel function, shorter recovery and hospital stay have also been shown in pancreas surgery, including high quality clinical trials[9-13]. Importantly, it has been reported that complication rates are lower after laparoscopic resection[9,14].

There has been recent interest in improving the oncologic aspects of distal pancreas resection with attention to margins and lymph node harvest, oncological surrogate markers for oncological resection. During open or laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy in patients with peripancreatic and retropancreatic invasion, negative surgical margins and appropriate lymph node harvest can be accomplished if wider and deeper dissection techniques are used[15,16]. It is unclear if this attention to a more radical resection has affected the practice of oncological surgical resection. Strasberg et al[16] reported that after open radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy procedure for patients with adenocarcionoma of the body and tail of the pancreas outside the capsule, a negative tangential margin was accomplished in 91% of the patients.

Recent reports have not shown any difference between open and laparoscopic operations in regards to these oncological surrogate markers[8,10,11,15,16].

Due to the association of higher hospital procedure volumes and improved clinical outcomes in complex oncologic operations, there has been interest in centralizing pancreas resections to high-volume hospitals. Current reports have documented the trend towards centralization of pancreatic procedures in the last decade, and report an improvement in perioperative mortality when these procedures are performed in high-volume hospitals[17-20]. It has not been determined whether this centralization has occurred with distal pancreas resection.

We sought to determine whether these concepts have gained any traction and are reflected in the trends of distal pancreas resections in the United States. Therefore we analyzed three major national databases with respect to inpatient outcome metrics, oncologic outcomes, and volume trends of patients with lesions of the neck and body of the pancreas that underwent a surgical resection.

From the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS, 2003-2009) and the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP, 2005-2010) databases we identified all patients with a diagnosis of a benign or malignant lesion of the body and/or tail of the pancreas that had undergone a partial or distal pancreatectomy. From the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER, 2003-2009) database we identified patients with diagnosis of a malignant lesion in the body and tail of the pancreas that underwent an operative resection. Patients from the NIS database were identified by the correspondent International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9) diagnosis and procedure codes (Table 1). In the NSQIP database patients were identified by a combination of ICD-9 diagnosis codes and current procedural terminology (CPT) codes. Utilization of laparoscopy was defined in NIS by the ICD-9 correspondent procedure code; and in NSQIP by the exploratory laparoscopy or unlisted procedure CPT codes. In SEER patients were identified by the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3) diagnosis codes and the SEER Program Code Manual, Third Edition procedure codes. Diagnoses and procedures codes are summarized in Table 1. Neither database enabled differentiation of whether laparoscopy was utilized for resection or diagnosis, and if diagnostic laparoscopy was followed by an open resection.

| ICD-9 codes | Description |

| Diagnosis | |

| Malignant neoplasms | |

| 157.1 | Body of pancreas |

| 157.2 | Tail of pancreas |

| 157.3 | Pancreas duct (Santorini and Wirsung) |

| 157.4 | Islets of Langerhans |

| 157.8 | Other specified sites of the pancreas (ectopic pancreatic tissue, malignant neoplasms of contiguous or overlapping sites of pancreas) |

| 157.9 | Pancreas, part unspecified |

| Benign neoplasms | |

| 211.6 | Benign neoplasms of pancreas except Langerhans |

| 211.7 | Benign neoplasm of islets of Langerhans |

| Procedure | |

| 52.5 | Partial pancreatectomy |

| 52.52 | Distal pancreatectomy |

| 52.53 | Radical subtotal pancreatectomy |

| 52.59 | Other partial pancreatectomy |

| 54.21 | Laparoscopy utilization |

| CPT codes | |

| 48140 | Pancreatectomy, distal subtotal, with or without splenectomy; without pancreaticojejunostomy |

| 48145 | Pancreatectomy, distal subtotal, with or without splenectomy; with pancreaticojejunostomy |

| 48999 | Unlisted procedure |

| 49320 | Exploratory laparoscopy |

| ICD-O-3 codes | |

| 25.1 | Body of the pancreas |

| 25.2 | Tail of the pancreas |

| SEER codes | |

| 30 | Partial pancreatectomy, NOS (distal pancreatectomy) |

| 80 | Pancreatectomy, NOS |

| 90 | Surgery, NOS |

Patients’ demographic characteristics included age, gender and body mass index. The comorbidities considered in NIS were acquired immune deficiency, alcohol abuse, iron deficiency anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, collagen vascular diseases, chronic blood loss anemia, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, coagulopathy, uncomplicated diabetes, diabetes with chronic complications, hypertension, liver disease, fluid and electrolyte disorders, obesity, peripheral vascular disorders, renal failure and cardiac valve disease. Postoperative complications of interest in NSQIP were superficial surgical site infection, deep incisional surgical site infection, organ space surgical site infection, pneumonia, unplanned intubation, pulmonary embolism, renal insufficiency, stroke with neurological deficit, coma, peripheral nerve injury, cardiac arrest requiring CPR, myocardial infarction, intraoperative or postoperative transfusions, deep vein thrombosis requiring therapy, sepsis and septic shock. The type of hospital (teaching or non-teaching) was assessed by a specific variable in the NIS database. We defined high volume hospitals as the top decile for volume (with ≥ 11 cases per year) over the course of this study (NIS).

In SEER, patient identification was performed using the Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER Stat software (seer.cancer.gov/seerstat) version 7.0.5.

In NIS and NSQIP patient identification and data analysis were performed with SAS software version 9.2. Statistical analysis of categorical variables was done with Fischer’s exact test. Continuous variables were analyzed with Wilcoxon test as data distribution for non-parametric data. Kendall correlation was done to assess for significance between body mass index (BMI) and year of operation. Linear regression was used to analyze for correlation between mortality and morbidity with operation approach. Logistic regression was used to analyze for trend significance of laparoscopy utilization and pancreas procedures performed in high volume hospitals or teaching hospitals during the course of the study. Survival was analyzed through Kaplan-Meier method.

From the NIS database 4242 patients were identified of which 2618 (62%) were female and 1612 (38%) were male; from NSQIP 2681 total patients were identified, 1581 (62%) female and 1093 (41%) male, and from SEER 1090 were identified, 599 (55%) female and 491 (45%) male. The mean age was 60.8 ± 15.1 years in NIS, 61.9 ± 13.8 years in NSQIP and 63.4 ± 13.3 years in SEER (mean ± SD). In NSQIP the BMI was 28 ± 6.6 kg/m2 (mean ± SD), and 335 (13%) of the patients had a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2. The overall BMI increased significantly during the course of the study (NSQIP, P = 0.04). There were 72% patients in NIS that had one or more comorbidities.

In NIS there were 2486 (59%) malignant lesions and 1756 (41%) benign lesions, whereas in NSQIP 1759 (66%) were malignant and 922 (34%) benign. In SEER, when compared by year of operation, no difference was seen in the median number of lymph nodes resected and the lymph node ratio in N1 disease (P = 0.17 and P = 0.96, respectively). Results by year are summarized in Table 2. Overall, when grouped by lymph node ratio, 45% were > 0-0.20 LNR, 28% were > 0.20-0.40 LNR and 27% with LNR > 0.40. The most common neoplasm types in patients that underwent an operation were adenocarcinoma in 52%, neuroendocrine (NE) in 27% and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) in 12% (SEER). Survival at 1 and 2 years was unchanged for resected patients with ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (1-year 63.6% and 2-year 35.1%, P = 0.53 and P = 0.21, SEER). Over the time covered in the study neither the IPMN nor NE 1 and 2 year survival changed (1-year 90%, and 2-year 84%, P = 0.15 and P = 0.25, SEER).

| Year | Number of lymph nodes resected | Lymph node ratio in N1 disease | ||||||

| n | Median | 1QR | 3QR | n | Median | 1QR | 3QR | |

| 2003 | 88 | 8 | 2 | 14 | 31 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.50 |

| 2004 | 133 | 7 | 4 | 13 | 66 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.50 |

| 2005 | 133 | 7 | 3 | 14 | 62 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.50 |

| 2006 | 160 | 8 | 5 | 13 | 71 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.45 |

| 2007 | 179 | 8 | 4 | 15 | 85 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.36 |

| 2008 | 315 | 9 | 5 | 16 | 94 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.40 |

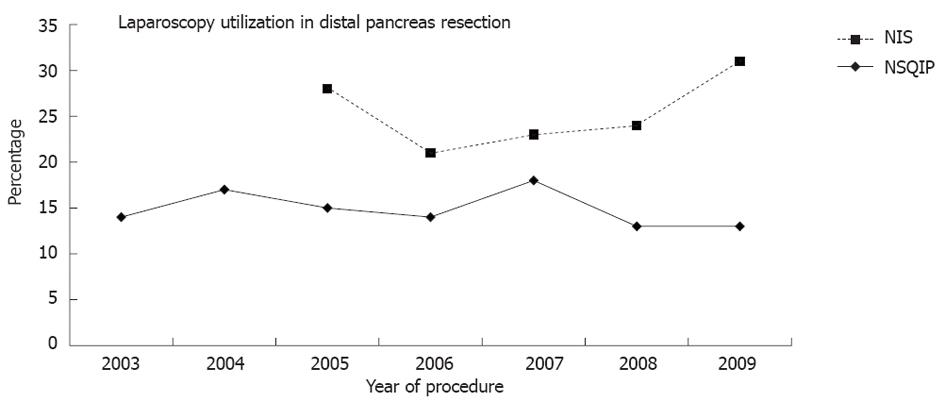

Overall, laparoscopy was utilized in 15% (NIS) and 27% (NSQIP) patients and 85% NIS and 73% NSQIP patients were performed through an open approach. During the course of the study the overall use of laparoscopy did not increase in either NIS (P = 0.51) or NSQIP (P = 0.54) datasets (Figure 1).

In patients with a comorbidity there was no difference in the utilization of laparoscopy (15%) in comparison to patients without any medical comorbidities (NIS, P = 0.96). Patients’ BMI was not associated with an operative approach (NSQIP, P = 0.95). Laparoscopy was utilized significantly more frequently in malignant lesions (21%) in comparison to benign lesions (8%; NIS, P < 0.001). In patients with malignant lesions spleen resection was performed more commonly (75%) in comparison to spleen preservation (25%; NIS, P < 0.001).

Utilization of laparoscopy did not correlate with type of hospital; utilization of laparoscopy occurs in 15% of resection in teaching hospitals and 14% were performed in non-teaching hospitals (NIS, P = 0.26).

The rate of reoperation was not different between laparoscopy utilization (4%) and open approach (4%, NIS, P = 1.0).

Overall, postoperative complications were less frequent after laparoscopy utilization (10%) in comparison to open approach (15%, NIS, P < 0.001). Postoperative complications occurred more commonly after resection of malignant lesions (12% vs 8%, NIS, P < 0.001). After resection of a malignant lesion complications were less frequent after laparoscopy utilization when compared to open approach (9% vs 18%, NIS, P < 0.001). Overall, the most frequent complications were intra-abdominal infection in 9%, sepsis in 7% and superficial site infection in 4% (NSQIP).

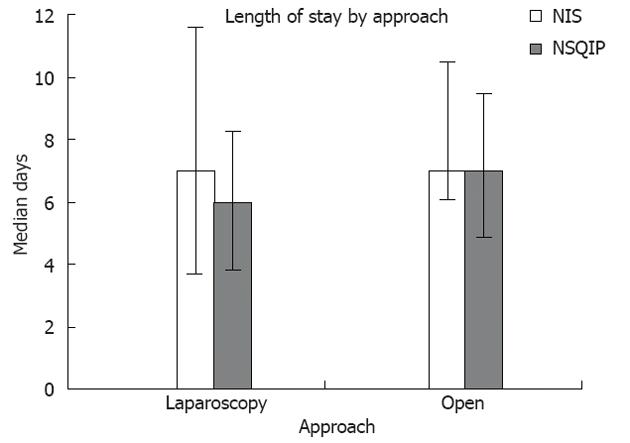

The overall length of stay was shorter when laparoscopy was utilized in comparison to open approach both in NIS [laparoscopy: 7 d, interquartile range (IQR) 4-11 vs open: 7 d, IQR 6-10, P < 0.001] and NSQIP (laparoscopy: 6 d, IQR 4-8 vs open: 7 d, IQR 5-9, P < 0.001; Figure 2). In both NIS and NSQIP the overall median length of stay was shorter after resection of a benign lesions (NIS, 7 d, IQR 5-9 vs NSQIP, 6 d, IQR 5-8) in comparison to malignant lesion (NIS, 8 d, IQR 6-11 vs NSQIP, 7 d, IQR 5-9, P <0.001), irrespective of approach.

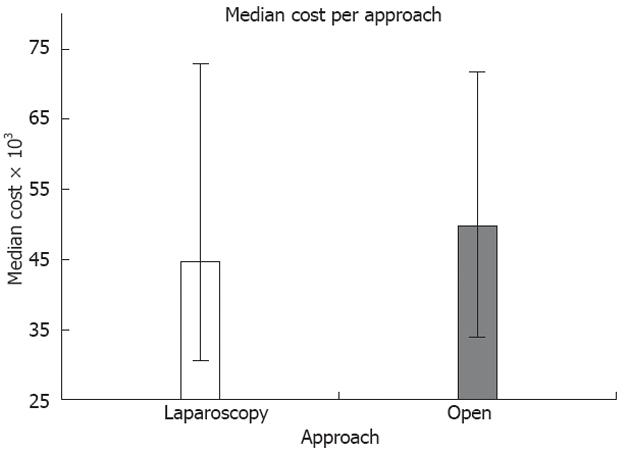

Regarding cost of care, there was a significantly lower total charge with laparoscopy utilization (median cost was 44 741 dollars, IQR 28 347-74 114 dollars) when compared to open approach (median cost was 49 792 dollars, IQR 13 299-73 463, NIS, P = 0.02) (Figure 3).

The hospital mortality rate was not different between laparoscopy utilization and open approach respectively (3% vs 2%, NIS, P = 0.05).

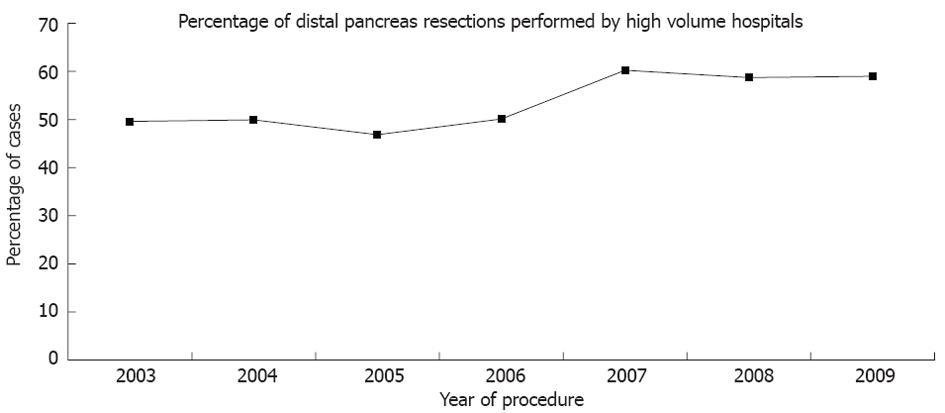

Of the 903 hospitals included in NIS, the top decile for volume included hospitals that performed greater than 11 cases per year. Overall, the fraction of total procedures of the distal pancreas performed by high volume hospitals did not increase significantly during the course of the study (NIS, P = 0.43) (Figure 4). A significant majority of the teaching hospitals (88%) were in the top decile of hospitals for volume (NIS, P < 0.001).

No significant difference was seen in the frequency of postoperative complications when analyzed by deciles of hospital volume; the complication rate for resection in the top decile hospitals was 14% and 15% in the lower decile hospitals (NIS, P = 0.99). Neither was a significant difference seen when analyzed by type of hospital; teaching hospitals and non-teaching hospitals had similar complication rate (15% vs 14% respectively, NIS, P = 0.72).

The NIS database is directed to determine health care utilization, access, charges, quality and outcomes[21]. NSQIP focuses on perioperative complications, with a mandate to determine the quality of surgical care[22] and SEER focuses on the incidence, prevalence and survival of cancer[23]. Taking into consideration the goal of each database, we amalgamated the available information from these respected datasets to obtain an integrated and broad nationwide analysis of distal pancreas resection. Specifically we found NIS useful to assess laparoscopy utilization and comorbidities, comparison of costs and analysis by hospital type (teaching and non-teaching). On the other hand, the NSQIP database is more appropriate for detailed analysis of perioperative complications and patient risk factors. Oncological metrics and outcomes are best assessed by the SEER database. All of these have limitations, but we believe that the nationwide databases are complementary to each other and it is helpful to present an analysis of them together. The limiting factor we encounter in both NIS and NSQIP is that procedures are grouped in broad categories, limiting the ability to distinguish the role of laparoscopy in each procedure. Though using the current coding system allowed for a general procedure analysis, an improvement in coding system that further categorizes procedures will facilitate a more detailed analysis.

Overall, we found that in patients where laparoscopy was utilized, the median length of stay was shorter. This reinforces the findings of single center studies[8,12,15,24]. Recently, Venkat et al[9] in a meta-analysis reported that patients that underwent a laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy had not just a lower blood loss and hospital length of stay, but also had fewer complications and surgical site infections. Importantly, no difference was found in operative time, margin positivity, incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula or mortality. Additionally, we found that utilization of laparoscopy reduced overall expenses; this finding is likely secondary to the shorter length of stay and lower complication rate.

Other recent reports have confirmed the advantages of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy over open approach, in terms of lower intraoperative blood loss, pain and analgesic requirements, earlier return of bowel function, shorter recovery and hospital stay[9,10,14,25,26]. Therefore, the subset of patients with medical comorbidities could potentially benefit more than healthier patients, but we did not find that patient morbidity was associated with use of minimally invasive surgery.

Despite the known and reported benefits, overall laparoscopy was utilized in 15% (NIS) and 27% (NSQIP) of the distal pancreas resection cases. This represents all patients that had laparoscopy performed for diagnosis, staging, resection or a combination of these procedures. The rate of utilization of laparoscopy has remained stable over most of the past decade, although we could not determine in each case the specific technique of laparoscopy used. The finding of no increase in utilization of laparoscopy could be explained by the low number of pancreas surgeons that perform laparoscopic pancreatic resection. Also, another potential explanation for this stable rate could be that more laparoscopic resections and fewer diagnostic staging procedures are being performed over the study course, but these changes could not be detected by our analysis.

In our analysis, we showed that laparoscopy was utilized more frequently in malignant lesions, which could be due to utilization of laparoscopy for diagnosis and/or staging purposes. Interestingly, we did not find that laparoscopy was utilized and performed more frequently in teaching or high volume hospitals, though we expected that teaching hospitals and specialized medical centers would perform more MIS resection cases. It is not surprising that NSQIP hospitals have a higher rate of laparoscopy utilization than NIS hospitals, because NSQIP hospitals have volunteered for the program in an effort to improve quality. But it would not be appropriate to further compare data across different databases.

No consensus exists for or against the use of laparoscopic approach for distal pancreatectomy in malignant lesions, though recent publications support this approach in selected patients[7]. It has also been reported that after laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy in patients with invasion, a resection to negative margins and adequate lymph node harvest can be accomplished[15]. We also found that postoperative complications were more common after resection of malignant lesions, but even in malignant lesions use of laparoscopy was associated with a decrease in complications. The reported laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy morbidity ranges from 20% to 47% and the reported mortality rate ranges from 3% to 5%[14,27,28]. Our study shows that nationwide mortality is at or below the benchmark reported data. The most common reported complications after laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy are pancreatic fistula, intra-abdominal abscesses, wound infection, sepsis, malabsortion, electrolyte disturbance and hemorrhage[14,27,28]. The rate of intra-abdominal infection we report (9%) is also at or below reported benchmarks. This may reflect inaccuracy of coding.

Regarding oncological outcomes, no increase was seen in the number of lymph nodes harvested and lymph node ratio in N1 disease. More importantly the 1-year and 2-year survival did not increase during the course of this study.

The oncological surrogate markers associated with survival in pancreas cancer such as tumor size, tumor differentiation, surgical margins, lymph node status and lymph node ratio have been well documented[8,10,11,15,29]. We speculate that surgeons might opt for open operation to enable a more radical oncologic resection. This however, does not appear to be the case, as survival and oncologic surrogate markers were unchanged over the course of the study. We believe that published data support using MIS to perform a more radical oncologic resection, but these data show this is not a common practice across the country[8,15,16,30].

Multiple reports support centralization of oncological pancreas procedures towards high-volume hospitals, and as a result of this, a decrease in mortality has also been reported[17-20]. Stitzenberg et al[18] analyzed the NIS database to assess cancer surgery centralization for pancreas, esophagus and colon cancer. Interestingly, during the course of the study there was a decrease in total number of hospitals performing pancreas procedures, but a statistical significant increase in the number of high-volume hospitals and a decrease in low-volume hospitals performing pancreatectomy procedures. All the high-volume centers were teaching hospitals. A total of 8.3% patients with a diagnosis of pancreas malignancy were admitted through an emergency room, and were more likely to have surgery done in a low-volume hospital.

Forces opposing the trend for centralization include the technological advances in imaging, resulting in diagnosis of pancreas lesions at earlier stages. Smaller lesions could potentially be managed in a non-specialized hospital, and only complicated cases referred to specialized hospitals. On the other hand, recent reports and guidelines support the use of endoscopic ultrasound with guided fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis and staging of body and tail pancreatic neoplasms[31,32]. This procedure is usually performed in specialized medical centers, which would support the concept of centralization. In our analysis, centralization of distal pancreas procedures over the last decade has not occurred.

Even though the definition of utilization of laparoscopy in our analysis was broad, it appears that at a nationwide level, laparoscopy is underutilized for distal pancreas resection despite sufficient evidence of its benefit. Centralization of distal pancreas resections to high volume centers does not appear to be occurring in the United States, but this does not appear to affect overall quality. During the course of this study survival and extent of lymph node harvest has not changed.

We can conclude that there is room for improvement in distal pancreas resection in the United States.

Laparoscopy utilization in pancreas operations has progressed at a slower pace when compared to procedures for other solid organs. Current reports have documented the trend towards centralization of proximal pancreatic procedures in the last decade, and improvement in perioperative mortality when performed in high-volume hospitals.

Database analysis allows assessment of trends across the spectrum of surgical practice in a country. Trends of distal pancreas resections in the United States were studied with respect to concepts of centralization of care, surgical technique, and clinical and oncological outcome metrics.

In patients where laparoscopy was utilized, there were fewer complications and surgical site infections, and decreased length of stay. Additionally, utilization of laparoscopy reduced overall expenses. The rate of utilization of laparoscopy has remained stable over most of the past decade. Interestingly, they did not find that laparoscopy was utilized and performed more frequently in teaching or high volume hospitals. Postoperative complications were more common after resection of malignant lesions. Regarding oncological outcomes, no increase was seen in the number of lymph nodes harvested and lymph node ratio in N1 disease. More importantly, the 1-year and 2-year survival did not increase during the course of this study. There was no trend for centralization of care for resection of lesions of the distal pancreas.

Utilization of laparoscopy during distal pancreas resection is associated with improved outcomes at a national level, when compared to open resection. These findings confirm results of recent multi-center studies.

From the Health Care Cost and Utilization Project, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database is directed to determine health care utilization, access, charges, quality and outcomes. The National Surgical Quality Improvement Project is a database from the American College of Surgery that focuses on perioperative complications, with a mandate to determine the quality of surgical care. The Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results by the National Cancer Institute focuses on the incidence, prevalence and survival of cancer.

Each database shows unique aspects of the trends in distal pancreatectomy, demonstrating their individual advantages and weaknesses. There appears to be an overall underutilization of laparoscopy for distal pancreatectomy across the United States despite the benefits demonstrated on multiple published series.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Thiruvengadam Muniraj, MD, PhD, MRCP, MBBS, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, 11123 Avalon Gates, Trumbull, CT 06611, United States

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 2. | Lillemoe KD, Kaushal S, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Distal pancreatectomy: indications and outcomes in 235 patients. Ann Surg. 1999;229:693-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 428] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mayo WJ. I. The Surgery of the Pancreas: I. Injuries to the Pancreas in the Course of Operations on the Stomach. II. Injuries to the Pancreas in the Course of Operations on the Spleen. III. Resection of Half the Pancreas for Tumor. Ann Surg. 1913;58:145-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Soper NJ, Brunt LM, Dunnegan DL, Meininger TA. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy in the porcine model. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:57-60; discussion 60-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: Is it worthwhile? J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:20-25; discussion 25-26. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Borja-Cacho D, Al-Refaie WB, Vickers SM, Tuttle TM, Jensen EH. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:758-765; quiz 800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gumbs AA, Chouillard EK. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy for malignant tumors. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:83-86. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Mabrut JY, Fernandez-Cruz L, Azagra JS, Bassi C, Delvaux G, Weerts J, Fabre JM, Boulez J, Baulieux J, Peix JL. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: results of a multicenter European study of 127 patients. Surgery. 2005;137:597-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Venkat R, Edil BH, Schulick RD, Lidor AO, Makary MA, Wolfgang CL. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is associated with significantly less overall morbidity compared to the open technique: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2012;255:1048-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 429] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kooby DA, Gillespie T, Bentrem D, Nakeeb A, Schmidt MC, Merchant NB, Parikh AA, Martin RC, Scoggins CR, Ahmad S. Left-sided pancreatectomy: a multicenter comparison of laparoscopic and open approaches. Ann Surg. 2008;248:438-446. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Rodríguez JR, Germes SS, Pandharipande PV, Gazelle GS, Thayer SP, Warshaw AL, Fernández-del Castillo C. Implications and cost of pancreatic leak following distal pancreatic resection. Arch Surg. 2006;141:361-365; discussion 366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Edwin B, Mala T, Mathisen Ø, Gladhaug I, Buanes T, Lunde OC, Søreide O, Bergan A, Fosse E. Laparoscopic resection of the pancreas: a feasibility study of the short-term outcome. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:407-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Patterson EJ, Gagner M, Salky B, Inabnet WB, Brower S, Edye M, Gurland B, Reiner M, Pertsemlides D. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: single-institution experience of 19 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jayaraman S, Gonen M, Brennan MF, D'Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, Allen PJ. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: evolution of a technique at a single institution. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:503-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Asbun HJ, Stauffer JA. Laparoscopic approach to distal and subtotal pancreatectomy: a clockwise technique. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2643-2649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Strasberg SM, Drebin JA, Linehan D. Radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy. Surgery. 2003;133:521-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, Brennan MF. Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. JAMA. 1998;280:1747-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1241] [Cited by in RCA: 1275] [Article Influence: 47.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Stitzenberg KB, Meropol NJ. Trends in centralization of cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2824-2831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Riall TS, Eschbach KA, Townsend CM, Nealon WH, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Trends and disparities in regionalization of pancreatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1242-1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stitzenberg KB, Sigurdson ER, Egleston BL, Starkey RB, Meropol NJ. Centralization of cancer surgery: implications for patient access to optimal care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4671-4678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Health Care Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2003-2009. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. |

| 22. | American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP). 2005-2010. Available from: http: //site.acsnsqip.org/. |

| 23. | National Cancer Institute Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER). 2003-2009. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/. |

| 24. | End Results (SEER). 2003-2009. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/. |

| 25. | Cuschieri A, Jakimowicz JJ, van Spreeuwel J. Laparoscopic distal 70% pancreatectomy and splenectomy for chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1996;223:280-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fernández-Cruz L, Cosa R, Blanco L, Levi S, López-Boado MA, Navarro S. Curative laparoscopic resection for pancreatic neoplasms: a critical analysis from a single institution. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1607-121; discussion 1607-1621;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jusoh AC, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy: a systematic review of comparative studies. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:904-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, Cheow PC, Ong HS, Chan WH, Chow PK, Soo KC, Wong WK, Ooi LL. Critical appraisal of 232 consecutive distal pancreatectomies with emphasis on risk factors, outcome, and management of the postoperative pancreatic fistula: a 21-year experience at a single institution. Arch Surg. 2008;143:956-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kleeff J, Diener MK, Z'graggen K, Hinz U, Wagner M, Bachmann J, Zehetner J, Müller MW, Friess H, Büchler MW. Distal pancreatectomy: risk factors for surgical failure in 302 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2007;245:573-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kooby DA, Hawkins WG, Schmidt CM, Weber SM, Bentrem DJ, Gillespie TW, Sellers JB, Merchant NB, Scoggins CR, Martin RC. A multicenter analysis of distal pancreatectomy for adenocarcinoma: is laparoscopic resection appropriate? J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:779-85, 786-7. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Shoup M, Conlon KC, Klimstra D, Brennan MF. Is extended resection for adenocarcinoma of the body or tail of the pancreas justified? J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:946-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dumonceau JM, Polkowski M, Larghi A, Vilmann P, Giovannini M, Frossard JL, Heresbach D, Pujol B, Fernández-Esparrach G, Vazquez-Sequeiros E. Indications, results, and clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2011;43:897-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |