INTRODUCTION

There is longstanding clinical knowledge that chronic alcohol misuse may cause severe liver damage. Hepatic steatosis is regarded as the early stage of alcohol-induced liver damage, and steatohepatitis may follow if alcohol misuse is continued. Liver cirrhosis as an end-stage of liver damage is accompanied by potentially life-threatening conditions including esophageal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, increased susceptibility to infections and impaired hemostasis.

It has been recognized for many decades that, apart from alcohol, other factors may induce complications, which resemble alcohol-related liver disorders in many ways[1]. In particular, obesity and metabolic syndrome, both with an increasing prevalence in developed communities, have been brought into scientific and clinical focus as risk factors for hepatic steatosis. Ludwig et al[2] described the potential role of obesity and metabolic syndrome in hepatic steatosis in their paper on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis as a hitherto unnamed disease, which was published in 1980. From that work, the term “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease has been established and is now commonly used to distinguish between obesity-related and alcohol-related hepatic steatosis.

Fatty liver disease is common in populations and has potential consequences for individual health. In Southern Italy, it was estimated from a population-based study[3] that alcohol misuse accounted for 46.5% of all cases diagnosed with impaired liver function, and a further 24.0% of cases were attributed to “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease. In Northeast Germany, where alcohol misuse, obesity and metabolic syndrome are highly prevalent[4-6], 29.9% of adults aged between 20 and 79 years had a hyperechogenic pattern in their liver ultrasound. Given the expected increase in the global burden of overweight and obesity[7], the prevalence of “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease will continue to rise over the next years. The potential impact of fatty liver disease for societies is reflected by the fact that, over the following five years, subjects with current hepatic steatosis will cause 26% higher health care costs compared to subjects without hepatic steatosis[8].

Currently, a large amount of research is being performed to explore risk factors, histopathological features, pathogenesis, clinical symptoms and options for the prevention and treatment of “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease. At this moment in time, it is common in research and clinical practice to distinguish between alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease. The rationale for this distinction, however, has not yet been the issue of thorough analyses.

This review uses the clinical-epidemiological perspective to critically assess whether it is necessary and useful to differentiate between alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease. The general aim of this review is to summarize the evidence that alcohol and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver diseases represent one and the same disorder with an underlying multicausal origin.

RESULTS

Definitions and risk factors

The term alcoholic fatty liver disease refers to hepatic steatosis and its liver-related sequelae, which are related to alcohol misuse, whereas the term “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease comprises the same liver disorders attributed to obesity and metabolic syndrome[12]. At a first glance, these definitions sound clear and intuitive, but there are at least five drawbacks for applying these definitions in clinical practice and research. These drawbacks are the main reason why the term “non-alcoholic” is put in quotation marks throughout this review.

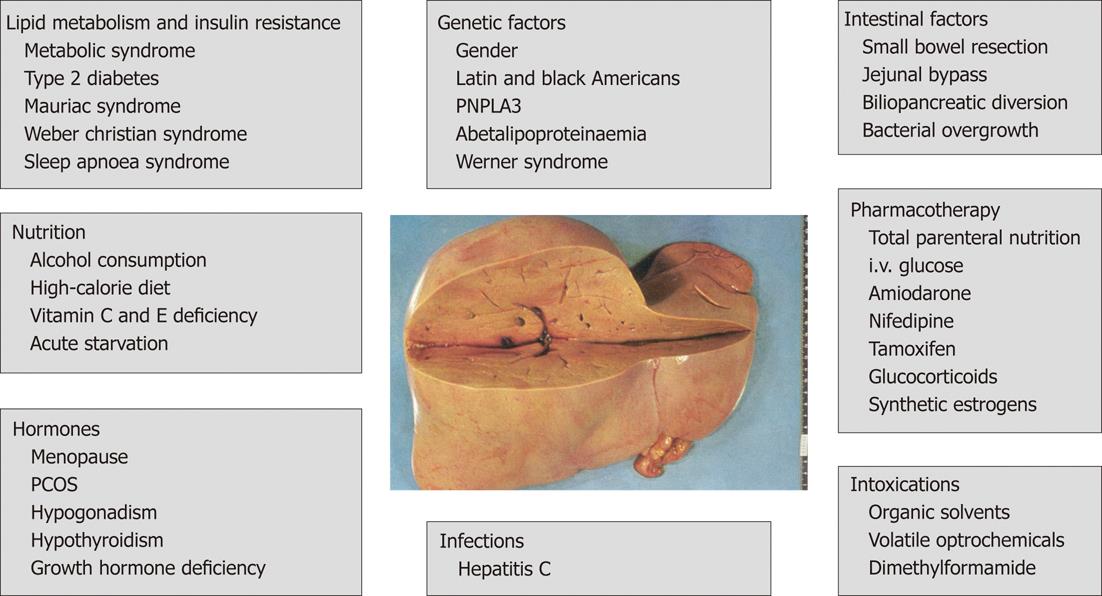

Firstly, the term “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease is imprecise. It implies that all risk factors for hepatic steatosis are summarized under this name. This, however, is not the case, because the term rather refers to the obesity-related causes that underlie the fatty liver disease. In addition to obesity and metabolic syndrome, other causes of fatty liver disease exist including other metabolic and hormonal disorders, acute starvation and abdominal surgery, as well as pharmacotherapeutic, toxic and genetic factors, which actually would have been also summarized under the term “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Risk factors for fatty liver disease[17,32,72,82-87].

PNPLA3: Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3; PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome.

Secondly, with regard to hepatic steatosis, there is no consistent definition of alcohol misuse. For example, some scientists[13,14] consider alcoholic fatty liver disease when men consume at least 80 g alcohol and define “non-alcoholic” liver disease by excluding patients who report a daily alcohol consumption of less than 20 g[15,16]. Unfortunately, subjects with alcohol consumption of between 20 g and < 80 g are not assigned to a specific group. The resulting practical problem is illustrated by SHIP data. In fact, 26.7% of all male participants aged 20 to 79 years had reported a daily alcohol consumption in the range of 20 g to < 80 g during the past 7 d.

Thirdly, the term “non-alcoholic” implies that alcohol plays no role in the development of fatty liver disease in affected patients. Certain amounts of alcohol consumption, however, are usually tolerated in the definition of “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease. Contrary to this, chronic daily alcohol consumption of e.g., 20 g may well increase the risk of liver damage in a considerable proportion of susceptible individuals. Thus, female sex, dietary habits, alcohol dehydrogenase deficiency and other genetic factors are major predictors of such increased susceptibility[17,18].

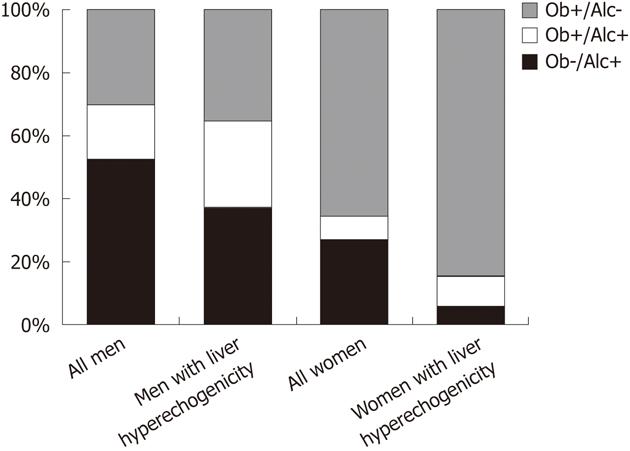

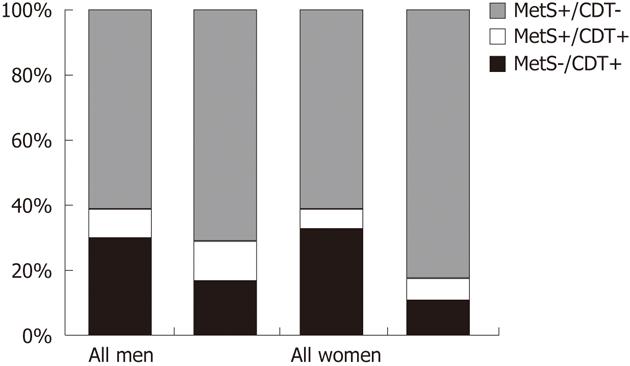

Fourthly, many cases cannot be clearly assigned to either the alcoholic or the “non-alcoholic” category, because an overlap between alcohol consumption and metabolic disorders exists within many individuals. SHIP data exemplify this issue (Figure 2). In the general adult population of Northeast Germany, obesity and harmful alcohol consumption are not mutually exclusive characteristics. Rather, a broad overlap between both characteristics exists, particularly in men. Among men who are either obese or report a daily alcohol consumption of > 30 g, 17.5% fulfill both criteria. In men with hyperechogenicity on liver ultrasound, this proportion is even as high as 27.3%. In women, for whom harmful alcohol consumption of > 20 g per day is much less prevalent than in men, the overlap is smaller and reaches a proportion of 7.3% in the whole female population and 9.4% in women with hyperechogenic findings on liver ultrasound. After applying stricter definitions for risk factors, metabolic syndrome[19] and increased serum carbohydrate-deficient transferrin levels are co-existent in 9.0% of men with at least one of both risk factors in the whole study population and in 11.7% in men with risk factors and liver hyperechogenicity, respectively (Figure 3). In women, these proportions are 5.8% and 7.3%. Similar findings were found in Finish adults[20], where subjects with alcoholic fatty liver disease were as often obese as subjects with “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease, and the metabolic syndrome was even more common in alcoholic than in “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease.

Figure 2 Obesity and alcohol consumption in the general population of Northeast Germany.

Data are taken from the population-based Study of Health in Pomerania. The columns indicate the proportions of obesity (Ob; body mass index > 30 kg/m²), harmful alcohol consumption (Alc; daily alcohol consumption > 20 g in women and > 30 g in men), the combined presence of both risk factors in all subjects (1122 men, 781 women) and subjects with a hyperechogenic pattern on liver ultrasound (535 men, 276 women), in whom at least one of both risk factors was present.

Figure 3 Metabolic syndrome and increased serum carbohydrate-deficient transferrin in the general population of Northeast Germany.

Data are taken from the population-based Study of Health in Pomerania. The columns indicate the proportions of metabolic syndrome (MetS), increased serum carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT > 6%), the combined presence of both risk factors in all subjects (970 men, 685 women) and subjects with a hyperechogenic pattern on liver ultrasound (486 men, 288 women), in whom at least one of both risk factors was present.

Current definitions of alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease disregard the common presence of risk factors for hepatic steatosis. What is the correct diagnosis for obese patients with hepatic steatosis who consume too much alcohol? Do they have alcoholic fatty liver disease, “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease or both? And how do we name fatty liver disease if one or more additional risk factors listed in Figure 1 are present? Furthermore, it has been convincingly demonstrated that metabolic factors contribute to the risk of pure steatosis in alcoholic patients. Apolipoprotein A1 levels, body mass index, waist circumference and blood pressure are closely associated with the risk of fatty liver in these patients[21]. On the other hand, especially in obese women, low amounts of alcohol may provoke the risk of “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease[22]. These data suggest that interactions among alcohol use, metabolic characteristics and other factors (Figure 1) do exist, and that the complexity of risk factor interplay is much greater than the simple distinction between alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease indicates.

Finally, misclassification due to information bias represents a serious problem in correctly distinguishing between alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” forms of fatty liver disease. Given the potential stigmatization through alcohol use among patients and study participants, the under-reporting of alcohol consumption is a common problem in clinical practice and research. Thus, it can be expected that a significant alcoholic component contributes to the development of “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease in a certain proportion of patients. Misclassification also arises from the fact that a history of alcohol consumption is usually evaluated in the present or for the very recent past. The Dionysos study[23,24] demonstrated, however, that life-time history of alcohol consumption is more valid to define a threshold for liver cirrhosis than is the current information. Studies performed in patients with “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease confirmed that misclassification was present in up to 10% of all cases[22].

Misclassification of alcohol consumption may also have biased studies[25-28], which suggested that low-to-moderate alcohol consumption is inversely associated with the risk of fatty liver diseases. The challenge in such studies is to correctly define the reference group. If this definition is only based on current self-reported denial of alcohol consumption, the reference group might not only include lifelong teetotallers, but also sick quitters with high alcohol-related morbidity[29]. This phenomenon may also have led to oversimplified interpretation of J-shaped associations between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular mortality[30,31] and should be considered in future studies on associations between alcohol consumption and fatty liver disease.

Taken together, the definitions of alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease are not very practical for clinical applications. The current concept of “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease does not sufficiently take into account risk factors for fatty liver disease other than obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Histopathology

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of fatty liver disease. The general stages of both alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease are as follows: (1) simple steatosis; (2) steatohepatitis; and (3) cirrhosis. Macrovesicular, microvesicular or mixed patterns of simple steatosis are the first step of both alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease[32,33]. The diagnostic criteria for steatohepatitis are steatosis accompanied by liver cell injury, inflammatory changes and fibrosis[32,34]. Common histopathological features of liver cell injury are ballooning of hepatocytes, vacuolated nuclei, Mallory bodies and megamitochondria. Inflammatory changes usually follow a lobular pattern. Perisinusoidal fibrosis typically occurs in acinar zone 3[32,34]. Cirrhosis, as an end stage of multiple liver disorders, is characterized by progressive perivenular fibrosis, which may form septa between terminal hepatic venulae. Regenerative nodules or diffuse pericellular fibrosis throughout the acini may develop if risk factors persist[32].

Several studies[34-36] have investigated the differences in the histopathological picture between alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease. In one study[35], patients with alcoholic fatty liver disease had a more diminished regional blood flow and hepatic oxygen consumption relative to patients with “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease, suggesting that a more impaired hepatic circulation exists in the former than in the latter. Although in this small study[35] both of the patient groups had an otherwise similar picture of hepatic steatosis, major differences existed in the extent of risk factors. Whereas the six patients with alcoholic fatty liver disease consumed a heavy amount of at least 180 g alcohol daily, the relatively moderate inclusion criterion for the “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease group was to be “at least 30% overweight in terms of ideal standards for height”[35]. Unfortunately, no further details on the distribution of metabolic risk factors were given in that study[35].

Regarding steatohepatitis, a previous review[34] has summarized current evidence by stating that the “non-alcoholic” form of steatohepatitis has greater amounts of steatosis and nuclear vacuolization, but less necroinflammatory activity, canalicular cholestasis, Mallory hyaline and periportal fibrosis than the alcoholic form. Although these differences probably exist, the limited comparability between patients with and without alcoholic steatohepatitis may limit the conclusions of many studies.

One example illustrates this notion. To investigate the histopathological disparities between patients with and without alcoholic hepatitis, Pinto et al[13] compared the histopathological characteristics of patients with “non-alcoholic” and alcoholic steatohepatitis, whereby the latter group was divided into ambulatory and hospitalized patients. In relation to hospitalized alcoholic patients, those with “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis had less severe histopathological signs of steatohepatitis, whereas ambulatory patients with alcoholic steatohepatitis displayed an intermediate histopathological picture.

Without a doubt, the study of Pinto et al[13] confirmed the expectation that the clinical presentation of patients with alcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with the histopathological severity of the disease. It still remains to be determined, however, whether it is also possible to conclude that “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis has a less severe histopathological pattern than the alcoholic form, because additional information on the clinical status of the patients would be necessary. Unfortunately, it is unclear from that study[13], whether the “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis patients were ambulatory or hospitalized. It has also not been stated what the indication of liver biopsy was in the “non-alcoholic” patients. Thus, it does seem likely that, for example, asymptomatic hepatomegaly in patients with known heavy alcohol consumption may be tolerated, since this finding is well explained by alcoholism; whereas the same constellation in patients who deny alcohol abuse gives rise to greater clinical efforts to find reasons for hepatomegaly. Hence, it is unclear whether the less severe clinical status in “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis patients and the earlier liver biopsy account for the lower severity of histopathological findings compared to patients with alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Furthermore, although Pinto et al[13] provide data on medication taken by the study patients, they leave uncertainty whether liver-related side effects of these drugs were suspected by treating physicians. Hence, it is not clear whether patients were correctly assigned to “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis as a metabolic liver disorder.

Taken together, although histopathological differences between alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease exist, the general pattern of findings is very similar. Therefore, pathologists are not able to distinguish between both entities by themselves without information on risk factors provided by clinicians[32,37,38].

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease has specific as well as common components. The relatively specific components of alcoholic fatty liver disease include the toxic effects of acetaldehyde and an increase in NADH[18,39] leading to acidosis, hypoglycemia and, as important factors for the development of hepatic steatosis, an increased activity of lipogenic pathways and a reduced export of triglycerides from the liver[18]. In “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease, insulin resistance activates the breakdown of peripheral adipose tissue with the consequence of increased hepatic absorption of free fatty acids, de novo synthesis of fatty acids and accumulation of triglycerides in the liver[18]. Furthermore, high serum insulin levels stimulate fatty acid synthesis and inhibit the conversion of triglycerides to very low density lipoproteins[18].

At least five common mechanisms exist that are important for the development and progression of both alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease. Firstly, inadequately high energy uptake may not only induce key mechanisms in “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease, but may also contribute to the alcoholic form of the disease. Alcoholic beverages are calorically dense, and in the absence of severe malnutrition in affected patients, this may result in an impaired energy balance in chronic alcoholism[36]. Secondly, triglycerides are synthesized from fatty acids in both forms of fatty liver disease. Fatty acids are mainly derived from lipolysis of adipose tissue, but may also be generated by de novo lipogenesis[36]. Thirdly, oxidative stress is highly relevant to the progression from hepatic steatosis to steatohepatitis and cirrhosis in both forms of fatty liver disease. In alcoholic fatty liver disease, ethanol generates free radicals, and the activation of CYP2E1 and mitochondrial activities release reactive oxygen species[18,40]. Free fatty acids and mitochondrial dysfunction seem to be key mediators for the inflammatory processes induced in “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease[41,42]. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are the major contributors to the progression from pure steatosis to steatohepatitis in both alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease[43-45]. Also, in both disease forms, inflammatory cytokines reduce insulin sensitivity and thereby increase the risk of fatty liver disease[45-47]. Fourthly, endotoxin, a toxic lipopolysaccharide located in the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria, enhances complications of fatty liver disease by stimulating inflammatory processes. In alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease, the release of endotoxin is triggered by increased gut permeability[18,48,49]. Finally, intestinal bacteria may add an alcoholic component to the pathogenesis of “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease. It has been demonstrated in mice studies that intestinal bacteria produce alcohol, and that the amount of alcohol production is higher in obese than in lean animals[50]. In line with these findings from animals, hepatocytes from young human patients with “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis and without any history alcohol consumption demonstrated expression of genes encoding all known pathways of alcohol degradation, which was much stronger than in hepatocytes from age-matched controls[51]. These findings support the notion that alcohol may play a central role in the development of “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis.

Taken together, there are, particularly in the early stages of fatty liver disease, some pathways that are specific for the underlying cause of the disease. In other important aspects, pathomechanisms leading to alcoholic as well as “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease share many similarities.

Clinical presentation

Upon investigation of the clinical status of patients with “non-alcoholic” compared to alcoholic fatty liver disease, studies usually find that the former patients are less symptomatic with nausea, abdominal pain, jaundice and gastrointestinal bleeding, than are the latter[37,52]. To interpret these findings correctly, the time of recruitment of patients for the studies during the course of the disease has to be taken into account. These studies[37,52] are commonly histology-based. Thus, the time of recruitment is the day the biopsy was performed. As already suggested above, invasive diagnostic procedures may be performed much later in the time course of the disease in patients with clear alcohol misuse than in those with no or less alcohol consumption. Thus, the longer exposure and, consequently, larger cumulative dose of risk factors may have significantly influenced the outcomes of studies comparing the clinical features between patients with and without alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Taken together, current research suggests that “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease is accompanied by relatively mild symptoms compared to alcoholic fatty liver disease, but studies generally lack a well-balanced standardization with respect to the extent of underlying risk factors.

Outcome

Hepatic complications: Pure hepatic steatosis is commonly regarded as a benign disorder. However, in both alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease, hepatic steatosis may progress to steatohepatitis. Fibrosis is regarded to be the result of wound healing following inflammatory changes. The final stage of alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease is liver cirrhosis. Hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis are also associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, and alcohol misuse and obesity are the most common risk factors for this malignant tumor in developed countries[53,54].

One study[37] has compared the histopathological patterns between consecutive patients with alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” hepatic steatosis, demonstrating an increased risk of steatohepatitis and fibrosis in patients with alcoholic relative to “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease. The conclusions from that study[37] are, however, hampered by the limited comparability between the exposure groups with respect to the extent of risk factors. The prevalence of liver fibrosis in patients who admittedly consumed at least 80 g alcohol daily was compared to that in “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease patients, of whom 77% had a body weight of > 10% above their ideal body weight. The higher grades of lobular inflammation, fibrosis and cirrhosis might well be explained by unbalanced risk factors in that study[37]. Another study[55] supports this notion. Histopathological findings were investigated in 160 patients with morbid obesity who underwent gastric bypass or gastric banding surgery. The proportion of “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis was 33.8% and thus reached higher percentages than have been previously described in heavy alcoholic drinkers[23].

Similar to the risk of pure steatosis, there is also a possible overlap of risk factors for steatosis-related sequelae. After investigating risk factors for steatohepatitis and liver cirrhosis in patients with alcoholic fatty liver disease, it was demonstrated that the co-existence of alcohol misuse with obesity and metabolic syndrome increases the risk of complications of alcoholic fatty liver disease[56]. Conversely, in patients with “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease, moderate and, particularly, heavy episodic alcohol consumption increases the risk of hepatic fibrosis[57].

A Danish register study[58] demonstrated that, after excluding patients with liver cirrhosis, both alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease was associated with an increased risk of primary liver cancer, and that this risk was higher in the alcoholic (standardized incidence ratio 9.5; 95% CI: 5.7-14.8) than in the “non-alcoholic” group (standardized incidence ratio 4.4; 95% CI: 1.2-11.8). Unfortunately, as is commonly inherent to register studies, only a limited amount of baseline data was available. Hence, uncertainty exists as to whether “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease was mainly due to obesity and metabolic syndrome or whether other causes were also present.

Taken together, given individual susceptibility, which cannot be fully defined by the current knowledge, hepatic steatosis may progress to steatohepatitits, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The major determinant for this progression is the persistence of risk factors, which has led to hepatic steatosis.

Extrahepatic complications: The association between hepatic steatosis and extrahepatic sequelae has become an important issue of current research. Since “non-alcoholic” hepatic steatosis is regarded to be closely related to metabolic syndrome, multiple studies have investigated its associations with atherosclerotic diseases[59-61] and diabetes mellitus[62-65]. Most of these studies[59,61-63,65], however, used the relatively unspecific serum transaminase levels to define the exposure variables and commonly did not compare the risks of the outcomes between subjects with “non-alcoholic” and alcohol-related fatty liver disease.

In SHIP, we extensively studied the associations between metabolic disorders and hepatic steatosis as defined by the combined presence of ultrasound and laboratory findings. We identified strong inverse relations of hepatic steatosis with the anabolic hormones testosterone in men[66] and insulin-like growth factor-1 in both genders[67]. All of these relations were independent of alcohol consumption. Moreover, stratified analyses in subjects who consume more or less alcohol did not reveal any significant difference between both groups. A recent case-control study confirmed that carotid intima-media thickness was higher in all patients with fatty liver disease compared to healthy controls, but there was no difference in intima-media thickness between patients with alcoholic or “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease[68].

Using the longitudinal data, we demonstrated that subjects with hyperechogenicity on liver ultrasound and increased serum alanine aminotransferase levels at baseline more commonly used health care services over the following five years[8]. Consequently, hepatic steatosis was also related to increased health care costs. Another analysis showed that increased serum γ-glutamyl transpeptidase levels were predictive of mortality if a hyperechogenic liver echo pattern was also present[69]. All of these associations of hepatic steatosis with mortality as well as future health care utilization and costs were independent of alcohol consumption. Also, stratification of the study population according to more or less alcohol consumption did not reveal any difference in the subgroups with respect to the outcomes.

In good agreement with the hypothesis that not only the risk of fatty liver disease itself but also its outcome is determined by multiple risk factors, the NHANES III study demonstrated that the components of the metabolic syndrome are associated with overall mortality in both “non-alcoholic” and alcoholic fatty liver disease[70]. In line with our findings, an extension of the aforementioned study by Cortez-Pinto et al[13,71] demonstrated that the clinical status of patients, but not the major cause of fatty liver disease, is predictive of the outcome. Patients with “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis as well as ambulatory and hospitalized patients with alcoholic hepatitis were followed up over a mean time of six years. Survival was similar between patients with alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis. Only the subgroup of hospitalized alcoholics had a shorter survival than patients with “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis[71]. As mentioned earlier, this finding might be explained by the more advanced disease stage of hospitalized alcoholics, when compared to patients with “non-alcoholic” steatohepatitis at the time of recruitment.

Taken together, it is still not clear whether extrahepatic complications of “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease are specific for the metabolic origin. Rather, it seems likely that fatty liver disease confers this risk, independent of its causes.

Prevention and therapy

The question arises as to whether specific strategies for primary and secondary prevention and treatment represent the major difference between alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease. In the former, abstinence from alcohol is the major goal, while in the latter the major challenge is improvement of insulin resistance. The most efficient risk factor reduction can be achieved by lifestyle changes. In patients with alcoholic fatty liver disease the major treatment target is total abstinence from alcohol, while in patients with “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease the central goal is weight reduction by calorie reduction and optimized food quality[18]. Treatment can be pharmacologically supported by drugs, which improve the insulin resistance[72].

From a more general perspective, risk factor reduction is the major principle of prevention and treatment in both forms of fatty liver disease. This more general perspective is particularly necessary, given the overlap between risk factors and their potential interactions.

Risk factor reduction is not only important to prevent the natural course of the disease from benign hepatic steatosis to steatohepatitis and cirrhosis, but it is also required to avoid recurrent fatty liver disease in allografts following liver transplantation[72]. This general statement is appropriate for both alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease and also holds true for alcoholic fatty liver disease with a “non-alcoholic” component and vice versa.

Beyond risk factor reduction and liver transplantation in end stage liver failure, no specific therapies for alcoholic fatty liver disease are currently accepted in clinical medicine, and none have proven to be exclusively sufficient in patients with “non-alcoholic” or alcoholic fatty liver disease. Thus, several therapeutic strategies that aim at, for instance, supporting the antioxidative system or reducing inflammation have been tested only in specific forms of fatty liver disease[18,72,73].

Taken together, risk factor reduction is the major goal of prevention and the basic principle of treating fatty liver disease.

CONCLUSION

This review followed the hypothesis that fatty liver disease is a multifactorial disease with alcohol consumption and metabolic factors being the most common risk factors. For many aspects, studies were found that directly confirmed the hypothesis. Other studies, which apparently did not support this notion, were critically assessed from the epidemiological perspective. Following the line of evidence presented herein, the hypothesis underlying the strict separation of alcoholic from “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease may be less justified than taking fatty liver disease as it probably is-a multifactorial disorder.

The current concept to distinguish between alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease is mainly based on the presence of alcohol misuse and obesity-related metabolic disorders as common risk factors and, at least evident for the early phase of the disease, specific pathogenetic mechanisms. This concept has, however, several limitations. These limitations include the clear distinction between both entities in the common presence of alcohol misuse and obesity-related metabolic disorders and the non-consideration of other causal factors listed in Figure 1. Both entities share similar histopathological patterns and pathways. Studies demonstrating differences in clinical presentation and outcome are sometimes biased by selection. Risk factor reduction is the main principle of prevention and treatment of both forms of the disease.

Fatty liver disease parallels other multicausal diseases in many aspects. For example, various risk factors for atherosclerosis have been established including tobacco consumption, obesity and metabolic syndrome. For all of these risk factors, specific pathways have been described[74,75]; the outcome following acute coronary syndrome or stroke differs depending on the type and amount of risk factors accumulated[76-78] and, beyond basic therapeutic principles, the choice of pharmaceutical drugs depends on the pattern of individual risk factor profiles. However, the presence of underlying risk factors is not mutually exclusive, the histopathological findings are not risk factor specific, and risk factor reduction is the main goal of primary and secondary prevention. In cardiovascular medicine, however, there is no concept to distinguish between tobacco and non-tobacco-related atherosclerosis.

The distinction between alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease is arbitrary and artificial. It should be replaced by a concept which regards fatty liver disease as a multicausal disorder. Such a concept opens up multiple questions, which are potentially of high clinical relevance. Examples of these questions are: Are there cumulative thresholds for the effect of risk factors for fatty liver disease and related complications, and how are those hypothetical thresholds decreased by the additional presence of other risk factors? As expected, the association between risk factors and alcoholic fatty liver disease follows a dose-response pattern[23]. Similar findings have been documented for “non-alcoholic” fatty liver disease. In the Dionysos study[79], the prevalence of hepatic steatosis was estimated to be 91% in obese, 67% in overweight and 24% in normal weight individuals. However, it still remains to be determined whether these risk factors interact with other factors listed in Figure 1. The multicausal approach could also be applied to investigation of the factors defining individual susceptibility for this multicausal disorder and its complications. From the clinical perspective, it would be highly valuable to explore risk scores similar to those scores established for coronary artery disease[80] or diabetes mellitus[81], for instance. Finally, complex therapeutic strategies, in addition to risk factor reduction, could be found.

In conclusion, alcoholic and “non-alcoholic” fatty liver diseases are one and the same disease caused by different risk factors. A shift from artificial categories to a more general approach to fatty liver disease as a multicausal disorder may optimize preventive strategies and help clinicians more effectively treat patients at the individual level.