INTRODUCTION

Glycerin enemas (GEs) are widely performed, but rectal perforations secondary to GEs are only occasionally reported[1]. These perforations usually occur when patients are in a seated or lordotic standing position. Once they lead to peritonitis, death is usually inevitable[2]. We successfully performed direct endoscopic abscess lavage and fistula closure using a double over-the-scope-clip (OTSC) technique (Ovesco Endoscopy GmbH, Tuebingen, Germany)[3,4] in two patients with rectal perforation and fistula caused by a GE. These procedures resulted in a dramatic improvement in each patient’s condition. Direct endoscopic lavage with a saline solution and double OTSC closure are very useful for pararectal abscesses and large fistulae closure (greater than 20 mm), respectively, in elderly patients in poor general condition who cannot undergo surgery[5-9].

CASE REPORT

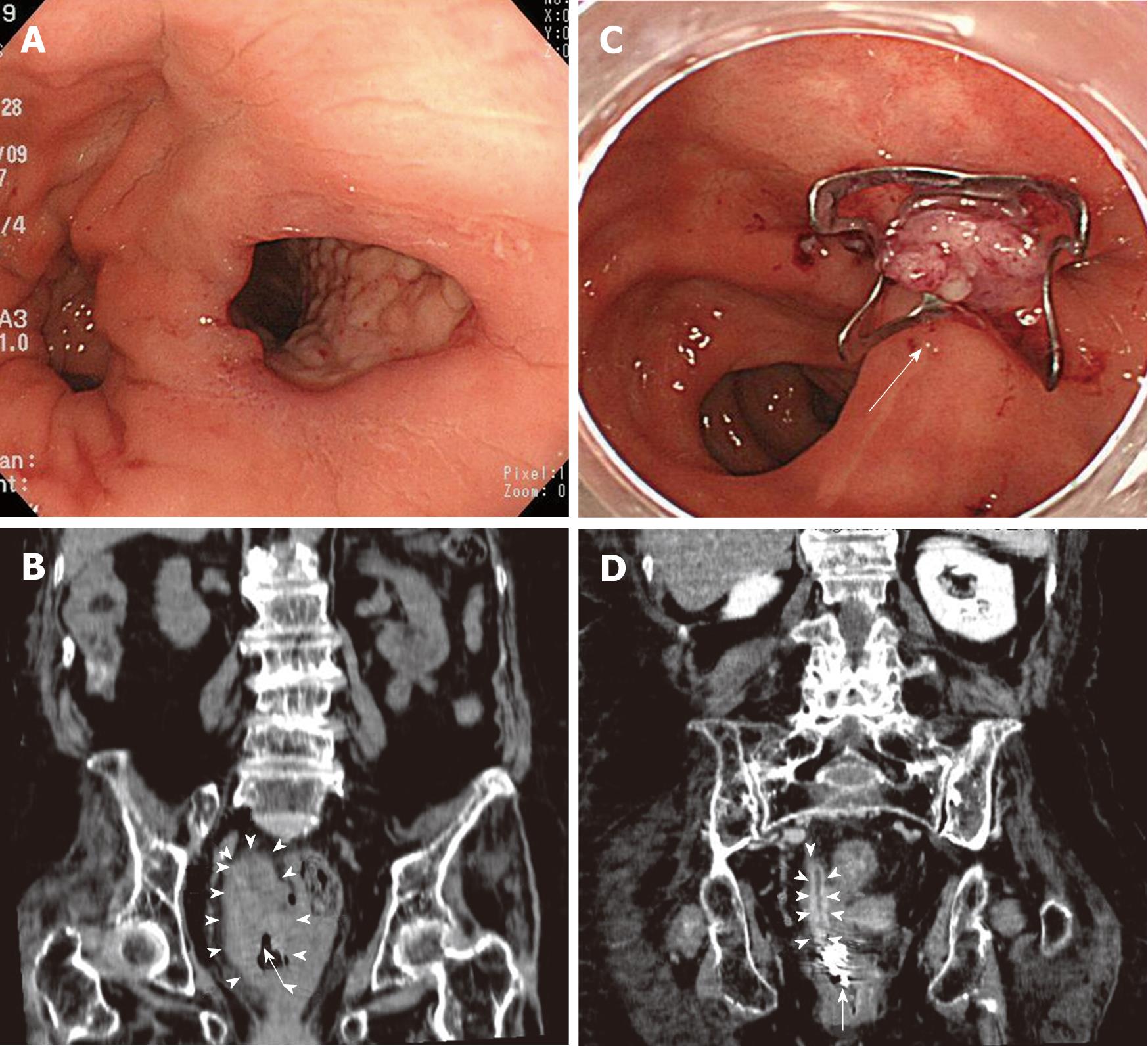

An 88-year-old bedridden woman experienced an acute onset of abdominal pain, high fever and melena. The laboratory examination revealed severe inflammation and anemia [white blood cell (WBC) 23 000/μL, hemoglobin (Hb) 6.6 g/dL, C-reactive protein (CRP) 23 mg/dL]. Three days later, a colonoscopy was performed, revealing a large fistula (20 mm) in the right rectal wall (Figure 1A). Computed tomography also revealed a large abscess in the right rectal wall (6 cm × 3 cm × 3 cm) (Figure 1B). Surgical closure was indicated but was impossible to perform given the patient’s poor overall condition. We informed her family that direct endoscopic abscess lavage and fistula closure with an OTSC would thus be required, and written informed consent was obtained from the family. The rectum was thoroughly washed with saline, and an endoscope with a water jet function was inserted into the abscess cavity that resulted from the fistula to wash out and lavage the pus and debris associated with the abscess. The abscess cavity was undercoated with pararectal fat tissue, which bled readily (Figure 2). The fistula was lavaged with 2 L of saline and then closed completely using the OTSC technique (Figure 1C). Five days later, the patient’s laboratory parameters had significantly improved (WBC 7800/μL, Hb 8.3 g/dL, CRP 7 mg/dL), and computed tomography revealed the disappearance of the abscess (Figure 1D). The overall time was 10 min, and there were no procedure-related complications. We administered an intravenous drip infusion of cefazolin (2 g/d) for two days following the closure of the fistula.

Figure 1 Colonoscopy and computed tomography of case 1.

A: Colonoscopy revealed a large fistula in the right side wall of the rectum; B: Computed tomography revealed a large abscess in the right rectal wall (6 cm × 3 cm × 3 cm in diameter) (arrowheads) and a fistula (arrow); C: After the lavage with 2 liters of saline, a colonoscopy was performed, and the fistula was completely closed using the over-the-scope-clip (OTSC) technique (arrow); D: Computed tomography revealed a remarkable disappearance of the abscess (arrowheads) and showed the OTSC (arrow).

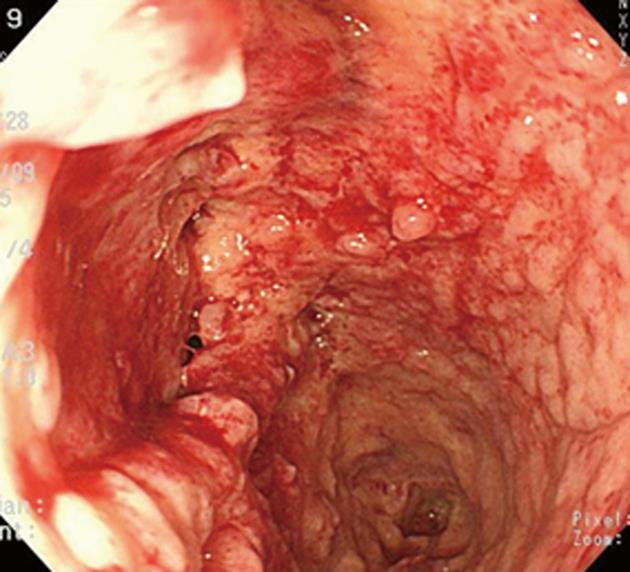

Figure 2 The abscess cavity lumen of case 1.

The abscess cavity was undercoated by pararectal fat tissue, which bled easily.

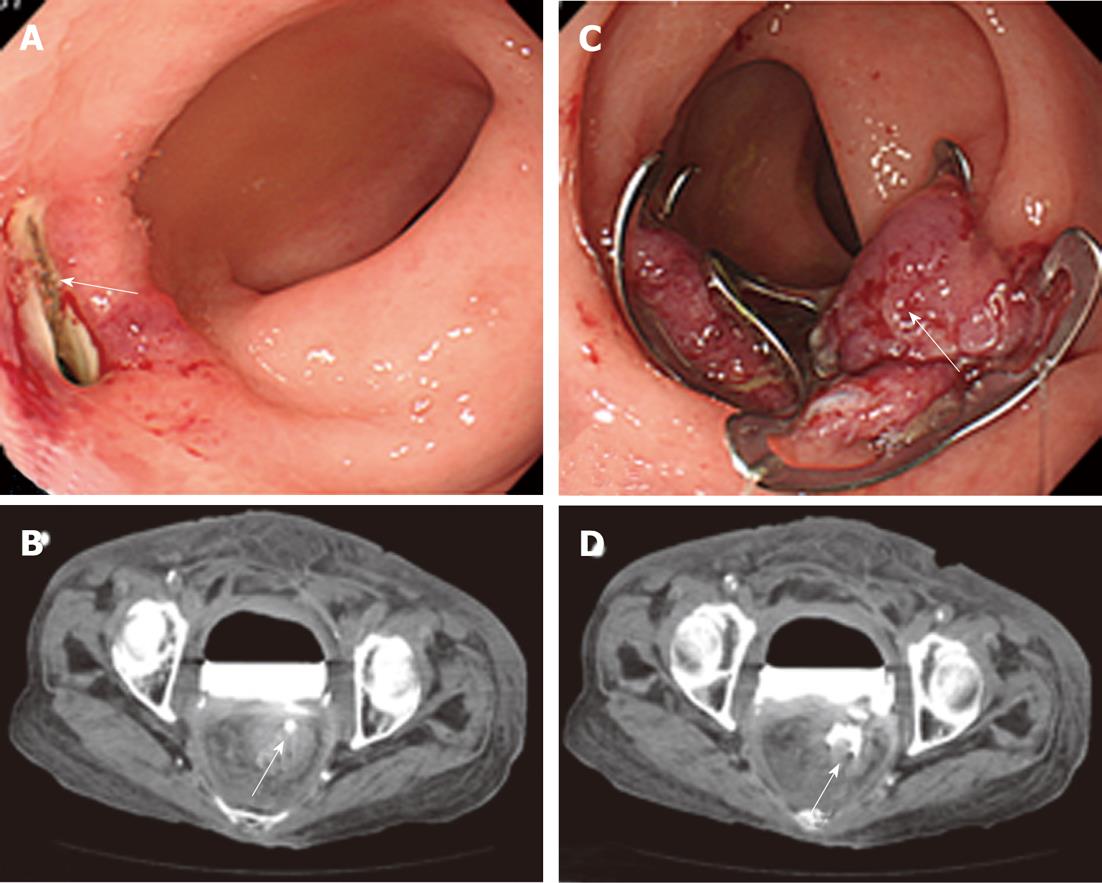

The second patient was a 78-year-old woman suffering from constipation. After receiving a GE, she experienced sudden, severe and sharp lower abdominal pain, a high fever and melena. Immediately after the onset of this sudden abdominal pain, an emergency colonoscopy revealed a large fistula (25 mm) in the ventral wall of the rectum (Figure 3A). After contrast radiography was used in the colonoscopy, computed tomography revealed the pooling of the radiocontrast agent in the urinary bladder and fistula (Figure 3B). We completely closed the fistula with a series of OTSCs (double OTSCs) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3 Colonoscopy and computed tomography of case 2.

A: Colonoscopy revealed a large fistula (25 mm) (arrow) in the ventral wall of the rectum; B: Following contrast radiography with a colonoscopy, computed tomography revealed the pooling of the radiocontrast agent in the urinary bladder and fistula (arrow); C: Complete closure of the fistula with a series of over-the-scope-clips (OTSCs) (double OTSCs) was performed (arrow); D: Computed tomography revealed the pooling of the radiocontrast agent in the urinary bladder and the complete closure of the fistula with double OTSCs (arrow).

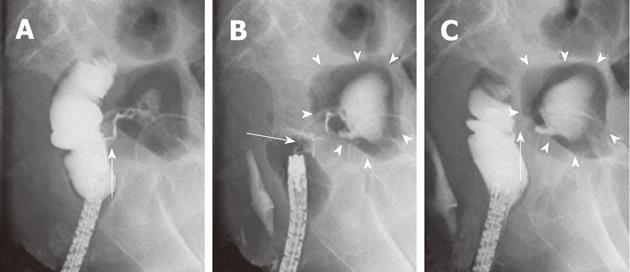

Computed tomography revealed the pooling of the radiocontrast agent in the urinary bladder and the complete closure of the fistula with double OTSCs (Figure 3D). The lateral view of the contrast radiography with the colonoscopy revealed a fistula leading to the urinary bladder, with inflowing and pooling of the radiocontrast agent in the urinary bladder (Figure 4A). Given the onset of the patient’s symptoms and these findings, we diagnosed a rectovesical fistula secondary to the tip of the GE. Because the fistula was a little larger than the OTSC, the single OTSC closure resulted in 1/3 of the fistula remaining (Figure 4B). We decided to close the fistula using double OTSCs. We succeeded in immediately closing the fistula with two OTSCs (Figure 4C). The overall procedure time was 20 min, and there were no procedure-related complications. After this series of OTSC closures, the patient’s laboratory data improved significantly, and computed tomography revealed the disappearance of the fistula.

Figure 4 The contrast radiography of case 2.

A: The lateral view of the contrast radiography and the colonoscopy revealed a fistula communicating with the urinary bladder and the inflowing and pooling of the radiocontrast agent in the urinary bladder (arrow); B: The fistula was slightly larger than the single over-the-scope-clip (OTSC). Single OTSC closure (arrow) resulted in 1/3 of the fistula remaining. Again, the contrast radiography revealed a residual fistula leading to the urinary bladder (arrowheads); C: The remaining fistula was completely closed with double OTSCs. The contrast radiography revealed no fistula leading to the urinary bladder (arrowheads). Tests revealed the successful closure of the fistula without any inflowing of the radiocontrast agent (arrow).

DISCUSSION

In the first case, rectal perforation led to a pararectal abscess. In the second case, the rectal fistula was caused by rectal perforation. Rectal perforation has been reported after GE when patients are in a seated or lordotic standing position[1,2]. We diagnosed the rectal perforation secondary to a GE partly based on the presentation of sudden abdominal pain, melena and a high fever. The perforation rate after a double-contrast barium enema is between 0.02% and 0.24%. Perforation remains an infrequent and almost certainly under-reported complication[3-5]. An iatrogenic perforation caused by a barium or GE as in our cases leads to serious conditions and adverse outcomes in elderly patients who are already in poor general condition.

Although perforation is a severe endoscopic complication, the OTSC procedure is reportedly very useful for the closure of the perforation site[6,7]. The OTSC is an endoscopic tool that allows for the application of a large claw-like clip for the endoscopic closure of full thickness wall defects within the gastrointestinal tract. It is a novel tool that can be safely and successfully employed to endoscopically close a fistula of the intestinal tract[8,9]. Studies report that the best indications for the use of OTSC are related to post-surgical fistulae and perforations due to colonoscopy. Defects ranging from 5 to 20 mm in the stomach and from 10 to 30 mm in the colon can be closed with a single OTSC, but tissue defects larger than 20-30 mm may require more than one OTSC to achieve adequate closure[10-15]. We successfully closed a perforation larger than 20 mm using a single OTSC and assessed the healing of the fistula by endoscopic or radiological means. Direct endoscopic lavage with a saline solution and double OTSC closures are very useful for the management of pararectal abscesses. In case 2, we closed a fistula larger than 25 mm with a series of OTSCs (double OTSCs) in an elderly patient in poor overall condition who could not undergo surgery. We did not experience any OTSC-related complications. The endoscopic closure of perforations and fistulae with OTSC is a simple and minimally invasive technique. Given the complete closure and healing of large fistulae with OTSC in our two cases, this approach may be less expensive and more advantageous than a surgical closure.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Benjamin Perakath, Professor, Department of Surgery Unit 5, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu 632004, India; Damian Casadesus Rodriguez, MD, PhD, Calixto Garcia University Hospital, J and University, Vedado, Havana City, Cuba; Kevin Cheng-Wen Hsiao, MD, Assistant Professor, Colon and rectal surgery, Tri-Service General Hospital, Taipei 114, Taiwan, China

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L