Published online Jun 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i23.2966

Revised: February 15, 2012

Accepted: February 26, 2012

Published online: June 21, 2012

AIM: To study the efficacy and factors associated with a sustained virological response (SVR) in chronic hepatitis C (CHC) relapsing patients.

METHODS: Out of 1228 CHC patients treated with pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV), 165 (13%) had a relapse. Among these, 62 patients were retreated with PEG-IFN-α2a or -α2b and RBV. Clinical, biological, virological and histological data were collected. Initial doses and treatment modifications were recorded. The efficacy of retreatment and predictive factors for SVR were analyzed.

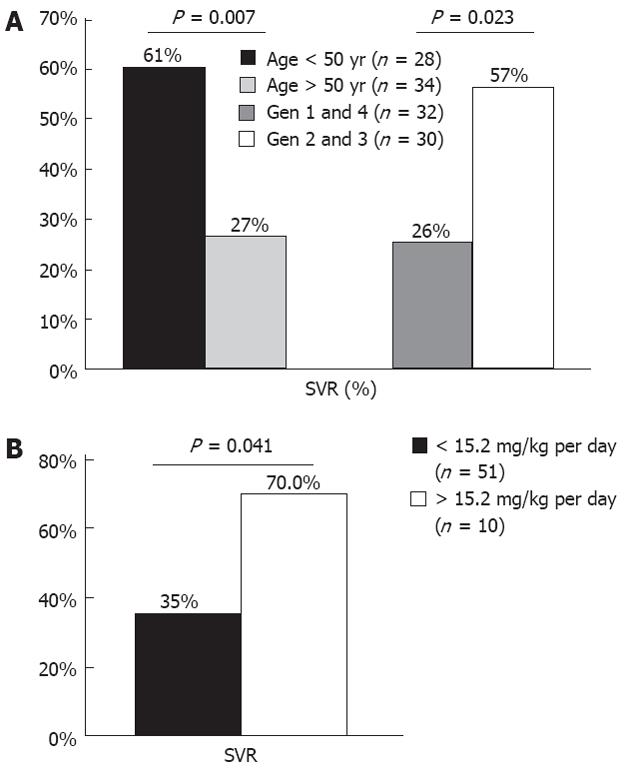

RESULTS: An SVR was achieved in 42% of patients. SVR was higher in young (< 50 years) (61%) than old patients (27%) (P = 0.007), and in genotype 2 or 3 (57%) than in genotype 1 or 4 (28%) patients (P = 0.023). Prolonging therapy for at least 24 wk more than the previous course was associated with higher SVR rates (53% vs 28%, P = 0.04). Also, a better SVR rate was observed with RBV dose/body weight > 15.2 mg/kg per day (70% vs 35%, P = 0.04). In logistic regression, predictors of a response were age (P = 0.018), genotype (P = 0.048) and initial RBV dose/body weight (P = 0.022). None of the patients without a complete early virological response achieved an SVR (negative predictive value = 100%).

CONCLUSION: Retreatment with PEG-IFN/RBV is eff-ective in genotype 2 or 3 relapsers, especially in young patients. A high dose of RBV seems to be important for the retreatment response.

- Citation: Stern C, Martinot-Peignoux M, Ripault MP, Boyer N, Castelnau C, Valla D, Marcellin P. Impact of ribavirin dose on retreatment of chronic hepatitis C patients. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(23): 2966-2972

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i23/2966.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i23.2966

Major advances have been made in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C (CHC) over the last decade. However, only 50% of patients will achieve a sustained virological response (SVR) with the combination of pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN)-α and ribavirin (RBV), the reference standard of care[1,2]. Hence, non-response and relapse are major issues. Approximately 30% of CHC patients with undetectable hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA at the end of therapy (EOT) will experience relapse[3].

Although its mode of action is not completely understood, RBV is clearly needed to improve SVR rates when combination therapy with PEG-IFN is prescribed[4]. The optimal dose of RBV to maintain the highest SVR rates differs according to genotype. The recommended RBV dose is 1000/1200 mg/d and 800 mg/d in HCV genotype-1 and genotype-2 or -3 infected patients, respectively[2,5]. Controversial studies showed that RBV dose, as well as RBV reduction and/or discontinuation during the first 12-24 wk of treatment could have an impact on the treatment response[6-12].

In addition to RBV dose and cumulative exposure, viral and host factors associated with a virological response were identified in naïve patients. The likelihood of a response is higher when patients have an early and long period of undetectable HCV RNA[13]. Patients who attain a rapid virological response and early virological response (EVR) have lower rates of relapse[14]. Also, older age, advanced liver fibrosis, high baseline viral load, infection with HCV genotype 1 and co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are known factors associated with treatment failure[2,13,15,16]. Recent data suggests that the type of PEG-IFN also has an impact on the outcome of HCV treatment. In the IDEAL trial, PEG-IFN-α2a and PEG-IFN-α2b in combination with RBV were compared. Although the EOT response was lower with PEG-IFN-α2b, higher relapse rates were observed with PEG-IFN-α2a. Therefore, the rates of SVR did not differ between the two types of PEG-IFN[13].

In contrast to the well-defined management of new HCV patients, relapsers are a challenge nowadays. There are no proven guidelines for retreatment of relapsers. Retreatment studies have been made based on heterogeneous groups. The majority of reports included both non-responders and relapsers and different previous therapies: IFN monotherapy, IFN plus RBV or PEG-IFN monotherapy. Overall SVR rates of 13%-50% were obtained in retreatment of patients who failed previous IFN-based therapy, with a higher SVR in former relapsers than in non-responders[17-21].

Thus, retreatment of relapsers with PEG-IFN plus RBV has not been well studied. The aim of this study was to evaluate, outside of trials, the efficacy of retreatment, and predictors of response, in a population of CHC relapsers after a previous course of PEG-IFN and RBV.

Patients with CHC who relapsed after a previous course of PEG-IFN-α2a or PEG-IFN-α2b in combination with RBV were eligible. Patients previously treated for at least 12 wk, with undetectable HCV RNA at the end of treatment and recurrence of viremia during 24-wk post-treatment follow-up were included in this retrospective cohort study. Exclusion criteria were co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus or HBV, the presence of any other cause of liver disease, decompensated liver disease and a history of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Patients were treated with PEG-IFN-α2a at a dose of 180 μg per week, plus weight-based oral RBV as previously described or PEG-IFN-α2b at the standard dose of 1.5 μg/kg body weight per week, in combination with oral RBV at a dose of 800-1200 mg per day, according to genotype and body weight[2,22]. The duration of therapy was determined according to genotype, duration of previous therapy, initial virological response and tolerability. Treatment prolongation and high RBV dose administration were decided case by case according to the physicians’ discretion. All patients had a post-treatment follow-up of at least 24 wk.

Serum HCV RNA level was measured at treatment initiation, treatment week 4, every 12 wk during the treatment period; and during post-treatment follow-up at weeks 4, 12 and 24. HCV RNA was detected qualitatively with the use of transcription-mediated assay (VERSANT HCV RNA Qualitative Assay; Siemens Medical Solution Diagnosis), which has a sensitivity of 9.6 IU/mL. A rapid virological response (RVR) was defined as undetectable HCV RNA at week 4 of treatment. An EVR was defined according to HCV viral load at week 12 and categorized as: no EVR (reduction of less than 2 log in HCV viral load compared with the baseline level); partial EVR (pEVR): reduction greater than 2 log; and complete EVR (cEVR): undetectable HCV RNA. Response to treatment was based on HCV RNA measurement at the end of therapy and at week 24 of follow-up. Non-responders were defined as detectable HCV RNA at EOT. Relapsers were defined as HCV RNA undectable at EOT but detectable within the 24-wk follow-up period. An SVR was defined as negative HCV RNA 24 wk after cessation of therapy. Pretreatment liver biopsies were analyzed by a single pathologist using the METAVIR scoring system.

Patients were evaluated for tolerability and safety by physical examination and laboratory evaluation, including hematological and biochemical analyses. Dose reductions or discontinuation of PEG-IFN or RBV (or both) were performed when appropriate, in accordance with guideline recommendations.

Univariate analysis was performed to evaluate treatment response and baseline characteristics. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 or F tests. Continuous variables were analyzed with the Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate. Predictors of response were identified and entered in a stepwise logistic regression in order to assess their association with SVR. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 and all comparisons were two-tailed. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chigago, IL).

Of 1228 CHC patients treated with a combination of PEG-IFN-α plus RBV in the Hepatology Department of Hôpital Beaujon, 165 (13%) patients were identified as relapsers and were eligible for this study. Retreatment was proposed for 75 patients. Among these, 62 consecutive patients were retreated between April 2003 and June 2008 and finished their follow-up period. Retreatment was prescribed with the same type of PEG-IFN-α used in the prior PEG-IFN combination treatment in 53% of patients. Median duration of therapy was 48 wk (16-72 wk). Retreatment was at least 24 wk longer than previous therapy in 51% of patients. Initial dose of RBV was >13.3 mg/kg per day in 54%. A high dose of RBV (daily doses > 15.2 mg/kg[22]) was prescribed in 16% of patients.

Baseline demographic, clinical, biochemical, virological and histological characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 52 years, and approximately 73% were male; 57% had a body mass index (BMI) > 25 kg/m2. Serum alanine aminotransferase and γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels were abnormal in 90% and 67% of patients, respectively. Forty-eight patients were infected with HCV genotype 1. High viral load (> 600 000 IU/mL) was observed in 28%. Necro-inflammatory activity was mild (A1) in 51% of patients, 34% had F2 fibrosis, 19% had advanced fibrosis (F3) and 39% had cirrhosis (F4). Steatosis was absent (< 5%) in 21%, mild (5%-30%) in 37%, and moderate or severe (> 30%) in 42% of patients.

| All patients (n = 62) | |

| Male gender | 45 (72.6) |

| Mean age, yr ± SD | 52 ± 9 |

| Mean weight, kg ± SD | 76 ± 14 |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2± SD | 26 ± 4 |

| Abnormal ALT | 54 (90) |

| Abnormal GGT | 36 (67) |

| Mean hemoglobin, g/dL ± SD | 14.8 ± 1.5 |

| HCV RNA | |

| > 600 000 IU/mL | 11 (28) |

| METAVIR fibrosis score | |

| F2 | 20 (34) |

| F3 | 11 (19) |

| F4 | 23 (39) |

| Steatosis | |

| < 5% | 13 (21) |

| 5%-30% | 23 (37) |

| > 30% | 26 (42) |

After retreatment with PEG-IFN and RBV, the overall SVR rate was 42%. An EOT response was achieved by 77% of patients (48/62); among them, 46% (22/48) again experienced a relapse. Patients < 50 years achieved a higher SVR rate (61%) when compared to older patients (27%) (P = 0.007). Female and male patients had SVR rates of 53% and 38%, respectively, but with no significant difference (P = 0.28). There was a trend for higher SVR rates in patients with normal baseline GGT (61% vs 36%, P = 0.081) and lower BMI (mean BMI 24.6 in SVR vs 26.5 in non responder, P = 0.071). In addition, patients infected with genotype 2 or 3 had higher SVR than those with genotype 1 or 4 (57% vs 28%, P = 0.023) (Figure 1A). SVR rates were similar regarding low and high viral load (41% vs 36%, P = 0.77). Necro-inflammatory activity, fibrosis and steatosis did not influence SVR rates.

Treatment responses according to dose and duration are summarized in Table 2. There was no difference between retreatment response with PEG-IFN-α2a or PEG-IFN-α2b regarding EOT (74% vs 84%, P = 0.52) and SVR rate (40% vs 47%, P = 0.56). Relapse rates were similar between groups (35% vs 37%, P = 0.68). In patients retreated with a different type of PEG-IFN-α from prior therapy, SVR was achieved in 36%, similar to that in patients retreated with the same PEG-IFN, who attained an SVR rate of 46% (P = 0.39). Retreatment for at least 24 wk longer than the previous therapy was associated with a higher SVR rate (53% vs 28%, P = 0.044). A high initial dose of RBV was associated with a higher likelihood of SVR. Although EOT response rates were not statistically different between groups (90% vs 75%, P = 0.43), patients who received > 15.2 mg/kg per day had a superior SVR rate when compared to patients receiving lower doses (70% vs 35%, P = 0.041) (Figure 1B). These results were related to a lower rate of relapse among patients with a high dose of RBV (20% vs 39%). Regarding RBV dose reduction, no impact on SVR rates was observed (43% among those patients without a reduction vs 33% with a dose reduction, P = 0.75).

| No. of patients, n (%) | SVR (%) | |

| Overall population | 62 (100) | 42 |

| Type of PEG-IFN (retreatment) | ||

| PEG-IFN-α2a | 43 (69) | 40 |

| PEG-IFN-α2b | 19 (31) | 47 |

| RBV ≥ 13.3 mg/kg per day | 34 (54) | 35 |

| RBV ≥ 15.2 mg/kg per day | 10 (16) | 70 |

| Treatment duration 24 wk longer than previous course | 31 (51) | 53 |

| Patients with RBV ≥ 15.2 mg/kg per day and 24 wk longer duration | 6 (10) | 67 |

Retreatment with combination therapy was well tolerated. Seventy-nine percent of patients did not reduce their initial dose of PEG-IFN and/or RBV. Only 4 patients (6.6%) had a reduction in PEG-IFN dose, 3 of whom had clinical intolerance with asthenia, and one had marked neutropenia. The reduction in RBV dose was necessary in 12 patients (19.7%), with anemia being the major reason (58%). Among all patients, only 2 had cumulative RBV doses lower than 80% of the predicted dose. High initial doses of RBV did not seem to influence RBV reduction. In patients with an initial dose of RBV > 13.3 mg/kg per day and in those with > 15.2 mg/kg per day, 26% and 30% of patients needed RBV dose reduction. The treatment was stopped earlier than the proposed therapy duration in 11 patients (18%). Among these, 10% did not achieve a virological response at week 24, and treatment was discontinued.

The factors identified in bivariate analysis as possibly associated with SVR and entered in a logistic regression model were: age, genotype, and high dose RBV. In the stepwise logistic regression analysis, the predictors of SVR were age [< 50 years vs≥ 50 years; odds ratio (OR), 4.26; 95% CI: 1.28-14.19], genotype (G2/3 vs G1/4; OR, 3.55; 95% CI: 1.01-12.46), and high dose RBV (> 15.2 mg/kg per day vs <15.2 mg/kg per day; OR, 6.99; 95% CI: 1.32-36.97). Younger patients with genotype 2 or 3 can attain an SVR of 59%, while older patients, infected with genotype 1 or 4 only had an SVR of 10%. None of the patients of older age, genotype 1 or 4, and RBV initial dose < 15.2 mg/kg per day achieved an SVR.

RVR was assessed in 39 patients; 18% (7/39) achieved an RVR, and 5 of these achieved an SVR [positive predictive value (PPV) = 71%]. In addition, RVR had a negative predictive value (NPV) for SVR of 88% (P = 0.007).

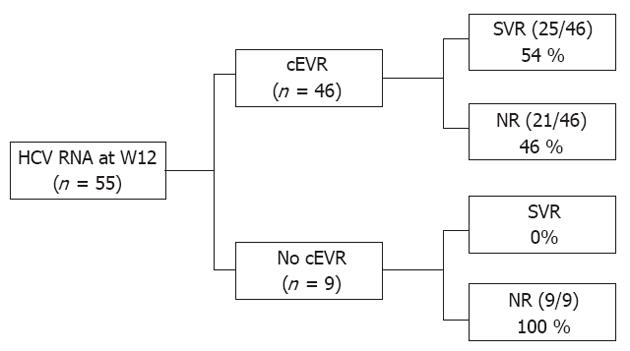

At week 12, 55 patients were classified according to the 3 categories of EVR described earlier. pEVR and cEVR were observed in 11% and 84% of patients. Patients with no EVR (3/55) or pEVR (6/55) did not attain an SVR (NPV = 100%). Among the 46 patients with cEVR, 4 (9%) were non-responders, 17 (37%) were relapsers and 25 (54%) had an SVR. cEVR had a PPV and a NPV for SVR of 54% and 100%, respectively (P = 0.003) (Figure 2).

Retreatment of CHC patients who have failed prior antiviral therapy is an important clinical issue. Our study evaluated the efficacy of retreatment of CHC patients who relapsed after combination therapy with PEG-IFN plus RBV. The overall SVR rate achieved was 42%. An important point of our study is the inclusion of a homogeneous population of prior relapsers to the PEG-IFN-α plus RBV combination therapy. Most previous studies analyzed the efficacy of retreatment with PEG-IFN plus RBV based on groups composed mainly of patients who failed conventional IFN-based therapy without distinguishing between non-responders and relapsers, or between monotherapy and combination therapy. Jacobson et al[21] demonstrated that SVR rates decreased according to previous conventional IFN-based therapy status: 42% in conventional IFN (cIFN) plus RBV relapsers, 21% in cIFN monotherapy non-responders, and 8% in cIFN plus RBV non-responders. These data were also confirmed by several other studies: retreatment of previous relapsers to cIFN plus RBV could achieve SVR rates of 41%-58%, while for patients who were non-responders, only 4%-26% achieved an SVR[17-21]. The same relationship was observed in previous failures to PEG-IFN and RBV: 33% in prior relapsers and 14% in prior non-responders, with an overall SVR of 22%[23].

The SVR rate of 42% observed in our study was slightly higher than that described in the EPIC3 clinical trial, where prior PEG-IFN plus RBV relapsers attained an SVR of 33%[23]. In our study, HCV genotype was an important predictor for SVR. Patients infected with genotype 2 or 3 attained the highest rates of SVR (60% in genotype 2 and 56% in genotype 3). Thus, a higher proportion of genotype non-1 infected patients in the current study (52% vs 20% in EPIC3 trial) could account for this difference. In addition, the EPIC trial used less sensitive qualitative assays that could result in misclassification of EOT responders, increasing the number of relapsers that were in fact non-responders, with a lower probability of SVR.

Young age and genotype 2 or 3 were factors associated with treatment response as previously reported[2,13,15]. We did not find a relationship between low baseline viral load or low fibrosis stage and better response to therapy. These factors have been described in controversial studies with the treatment of naïve and IFN-experienced patients, and their impact on the response in relapsers could have less strength[7,13,19,23,24].

Retreatment with only PEG-IFN-α in patients who failed to respond to the other PEG-IFN-α has been described as an alternative strategy. However, in our study no gain was observed in patients who received a different type of PEG-IFN-α. This finding is consistent with the REPEAT trial, where prior non-responders to PEG-IFN-α2b were retreated with PEG-IFN-α2a. Only 9% of SVR was observed in the regimen of 48 wk retreatment[25]. Besides, this trial demonstrated higher SVR rates in the group retreated for 72 wk (14%)[26]. In the current study, the SVR rate was also improved with longer duration of therapy. Thus, retreatment for at least 24 wk longer than the previous course is important to increase the probability of SVR in relapsers and non-responders.

Some controversial studies have suggested that exposure to RBV is critical for attaining an SVR. At first, adherence to therapy was considered extremely important. McHutchison et al[8] demonstrated that at least 80% adherence to therapy enhanced SVR. They found a continuous, increasing relationship between adherence and SVR in genotype 1. These findings were also observed in another study with genotype 1-naïve patients, where a linear relationship between exposure and the SVR rate was observed at the first 12 wk of treatment[7]. Also, a study with RBV discontinuation in a subset of HCV RNA-negative patients at week 24 showed an increase in the rate of virological breakthrough and relapse[9]. In contrast, in our study no relation was found between dose reduction of RBV and SVR. However, the rate of RBV reduction was 20% and only 2 patients did not have at least 80% of the predicted RBV doses.

Recent studies suggested that high-dose RBV schedules reduced relapse rates and increased SVR in difficult-to-treat selected patients[10-12]. In a pilot study with 10 genotype 1 patients, higher RBV doses were associated with more frequent and serious adverse events, but the SVR rate was 90%[11]. Also, Fried et al[10] reported a study with 188 treatment-naïve, genotype 1 and high viral load patients. Patients who received an RBV dose of 1600 mg/d had superior SVR rates when compared with standard doses (1200 mg/d). Our data demonstrated a clear relation between high initial dose of RBV[22] and SVR rates. Patients with RBV dose >15.2 mg/kg per day achieved an SVR rate of 70%, while only 26% of patients with lower doses attained an SVR.

Our study demonstrates that an RVR in a relapser retreatment population is attained by 18%, of whom 71% achieved an SVR. Prediction of non response on treatment was more marked with EVR analyses. If the patient did not achieve a cEVR, no SVR was observed (NPV = 100%). Hence, the presence of detectable HCV RNA at week 12 is a good indication to stop treatment in relapsers and it is as relevant as for naïve or non-responding patients[3,19,25].

Specifically targeted antiviral therapies for hepatitis C are currently under evaluation in clinical trials. These new drugs are mostly effective and have been studied in genotype 1 patients[27-29]. Telaprevir, an antiprotease NS3-NS4A, increases SVR rates in genotype 1 naïve and non-responding patients, but it has limited activity against genotype 2 and 3[30]. Besides, even when these medications will be available outside trials, they will not be accessible worldwide. For these reasons, PEG-IFN and RBV still have a role on hepatitis C retreatment, in particular in young patients infected with non genotype 1.

In conclusion, our study shows that retreatment of prior relapsers after treatment with a combination of PEG-IFN plus RBV may be effective. As observed with naïve patients, genotype is crucial for a treatment response. Better results of retreatment are obtained in patients with genotype 2 or 3 and of younger age. In addition, in this subset of patients, higher SVR rates are achieved with increased doses of RBV, without a marked increase in adverse events or dose reductions. Thus, a high dose schedule of RBV is recommended if retreatment is proposed. Also, prolonging therapy for at least 24 wk more than the previous course enhances SVR rates. Finally, the absence of a cEVR as defined by detectable HCV RNA at week 12 should be considered a stopping rule in the retreatment of relapsers.

Only 50% of chronic hepatitis C (CHC) patients treated with the combination of pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN)-α and ribavirin (RBV), the standard treatment, will achieve a sustained virological response (SVR). Therefore, patients with no response or relapse after PEG-IFN and RBV treatment are a major issue. Approximately 30% of CHC patients with undetectable hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA at end of therapy (EOT) will experience relapse.

Retreatment of CHC patients with relapse to antiviral therapy is a current clinical issue. There are no specific recommendations about type, dose and duration of retreatment in this particular situation. In this research area, different dose schedules and duration of PEG-IFN and RBV therapy have been evaluated in order to increase the SVR in patients with a previous relapse to this antiviral therapy.

This study shows in a real life cohort that retreatment of relapsers after prior treatment with a combination of PEG-IFN plus RBV may be effective. Better results of retreatment are obtained in patients with genotype 2 or 3 and of younger age as is observed in naïve patients. Moreover, in this subset of patients, higher SVR rates are achieved with increased doses of RBV (> 15.2 mg/kg per day), without a marked increase in adverse events or dose reductions. Also, lengthening therapy for at least 24 wk more than the previous course enhances SVR rates.

The study suggests that retreatment of patients with a relapse after treatment with PEG-IFN and RBV may be effective, especially in patients with genotype 2 or 3 who are of younger age. In order to increase SVR in this particular situation, high dose RBV and longer duration of therapy should be proposed.

In CHC patients, treatment responses to the combination of PEG-IFN and RBV are defined by a virological parameter (HCV RNA analysis) rather than a clinical endpoint. The most important definitions are: SVR if HCV RNA remains undetectable 24 wk after EOT, non response if HCV RNA is positive at EOT, and relapse if HCV RNA is undetectable at EOT but detectable within 24-wk follow-up period.

The authors revealed that SVR was achieved in 42% of the retreated patients, and that initial dose/weight of RBV was an important predictor of SVR.

Peer reviewers: Eric R Kallwitz, Assistant Professor, Univer-sity of Illinois, 840 S Wood Street MC 787, Chicago, IL 60612, United States; Satoshi Yamagiwa, MD, PhD, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, 757 Asahimachi-dori 1, Chuo-ku, Niigata 951-8510, Japan

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Marcellin P. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C in 2009. Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2320] [Cited by in RCA: 2241] [Article Influence: 140.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Martinot-Peignoux M, Stern C, Maylin S, Ripault MP, Boyer N, Leclere L, Castelnau C, Giuily N, El Ray A, Cardoso AC. Twelve weeks posttreatment follow-up is as relevant as 24 weeks to determine the sustained virologic response in patients with hepatitis C virus receiving pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Hepatology. 2010;51:1122-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dusheiko G, Nelson D, Reddy KR. Ribavirin considerations in treatment optimization. Antivir Ther. 2008;13 Suppl 1:23-30. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, Ramadori G, Bodenheimer H, Bernstein D, Rizzetto M. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346-355. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Shiffman ML, Ghany MG, Morgan TR, Wright EC, Everson GT, Lindsay KL, Lok AS, Bonkovsky HL, Di Bisceglie AM, Lee WM. Impact of reducing peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin dose during retreatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:103-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bain VG, Lee SS, Peltekian K, Yoshida EM, Deschênes M, Sherman M, Bailey R, Witt-Sullivan H, Balshaw R, Krajden M. Clinical trial: exposure to ribavirin predicts EVR and SVR in patients with HCV genotype 1 infection treated with peginterferon alpha-2a plus ribavirin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | McHutchison JG, Manns M, Patel K, Poynard T, Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Dienstag J, Lee WM, Mak C, Garaud JJ. Adherence to combination therapy enhances sustained response in genotype-1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1061-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 750] [Cited by in RCA: 736] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bronowicki JP, Ouzan D, Asselah T, Desmorat H, Zarski JP, Foucher J, Bourlière M, Renou C, Tran A, Melin P. Effect of ribavirin in genotype 1 patients with hepatitis C responding to pegylated interferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1040-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fried MW, Jensen DM, Rodriguez-Torres M, Nyberg LM, Di Bisceglie AM, Morgan TR, Pockros PJ, Lin A, Cupelli L, Duff F. Improved outcomes in patients with hepatitis C with difficult-to-treat characteristics: randomized study of higher doses of peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin. Hepatology. 2008;48:1033-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lindahl K, Stahle L, Bruchfeld A, Schvarcz R. High-dose ribavirin in combination with standard dose peginterferon for treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:275-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Snoeck E, Wade JR, Duff F, Lamb M, Jorga K. Predicting sustained virological response and anaemia in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus ribavirin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:699-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McHutchison JG, Lawitz EJ, Shiffman ML, Muir AJ, Galler GW, McCone J, Nyberg LM, Lee WM, Ghalib RH, Schiff ER. Peginterferon alfa-2b or alfa-2a with ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:580-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 894] [Cited by in RCA: 886] [Article Influence: 55.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Farnik H, Mihm U, Zeuzem S. Optimal therapy in genotype 1 patients. Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Heathcote J. Retreatment of chronic hepatitis C: who and how? Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:49-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Martinot-Peignoux M, Boyer N, Pouteau M, Castelnau C, Giuily N, Duchatelle V, Aupérin A, Degott C, Benhamou JP, Erlinger S. Predictors of sustained response to alpha interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1998;29:214-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Parise E, Cheinquer H, Crespo D, Meirelles A, Martinelli A, Sette H, Gallizi J, Silva R, Lacet C, Correa E. Peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) (PEGASYS) plus ribavirin (COPEGUS) in retreatment of chronic hepatitis C patients, nonresponders and relapsers to previous conventional interferon plus ribavirin therapy. Braz J Infect Dis. 2006;10:11-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Basso M, Torre F, Grasso A, Percario G, Azzola E, Artioli S, Blanchi S, Pelli N, Picciotto A. Pegylated interferon and ribavirin in re-treatment of responder-relapser HCV patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:47-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Moucari R, Ripault MP, Oulès V, Martinot-Peignoux M, Asselah T, Boyer N, El Ray A, Cazals-Hatem D, Vidaud D, Valla D. High predictive value of early viral kinetics in retreatment with peginterferon and ribavirin of chronic hepatitis C patients non-responders to standard combination therapy. J Hepatol. 2007;46:596-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sagir A, Heintges T, Akyazi Z, Oette M, Erhardt A, Häussinger D. Relapse to prior therapy is the most important factor for the retreatment response in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Liver Int. 2007;27:954-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jacobson IM, Gonzalez SA, Ahmed F, Lebovics E, Min AD, Bodenheimer HC, Esposito SP, Brown RS, Bräu N, Klion FM. A randomized trial of pegylated interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin in the retreatment of chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2453-2462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shiffman ML, Salvatore J, Hubbard S, Price A, Sterling RK, Stravitz RT, Luketic VA, Sanyal AJ. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 with peginterferon, ribavirin, and epoetin alpha. Hepatology. 2007;46:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Poynard T, Colombo M, Bruix J, Schiff E, Terg R, Flamm S, Moreno-Otero R, Carrilho F, Schmidt W, Berg T. Peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin: effective in patients with hepatitis C who failed interferon alfa/ribavirin therapy. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1618-1628.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4847] [Cited by in RCA: 4748] [Article Influence: 206.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jensen DM, Freilich B, Andreone P, Adrian DiBisceglie, Carlos E. Brandao-Mello, K. Rajender Reddy, Antonio Craxi, Antonio Olveira Martin, Gerlinde Teuber, Diethelm Messinger, Greg Hooper, Matei Popescu and Patrick Marcellin. Pegylated interferon alfa-2a (40kD) plus ribavirin (RBV) in prior non-responders to pegylated interferon alfa-2b (12kD)/RBV: final efficacy and safety outcomes of the REPEAT study. Hepatology. 2007;46 Suppl 1:291A-292A. |

| 26. | Jensen DM, Marcellin P, Freilich B, Andreone P, Di Bisceglie A, Brandão-Mello CE, Reddy KR, Craxi A, Martin AO, Teuber G. Re-treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C who do not respond to peginterferon-alpha2b: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:528-540. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Mchutchison JG, Everson GT, Gordon SC, Jacobson I, Kauffman R, McNair L, Muir A. Prove1: results from a phase 2 study of Telaprevir with peginterfeon alfa-2a and ribavirin in treatment-naive subjects with hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2008;48 Suppl 2:S4. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Asselah T, Benhamou Y, Marcellin P. Protease and polymerase inhibitors for the treatment of hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:57-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hézode C, Forestier N, Dusheiko G, Ferenci P, Pol S, Goeser T, Bronowicki JP, Bourlière M, Gharakhanian S, Bengtsson L. Telaprevir and peginterferon with or without ribavirin for chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1839-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 849] [Cited by in RCA: 794] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Foster GR, Hezode C, Bronowicki JP, Carosi G, Weiland O, Verlinden L, van Heeswijk R, Van Baelen B, Picchio G, Beumont-Mauviel M. Activity of telaprevir alone or in combination with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in treatment-naive genotype 2 and 3 hepatitis-c patients: final results of study C209. J Hepatol. 2010;52 Suppl 1:S27. [DOI] [Full Text] |