Published online May 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i19.2396

Revised: March 2, 2012

Accepted: March 20, 2012

Published online: May 21, 2012

AIM: To describe characteristics of a poorly expandable (PE) common bile duct (CBD) with stones on endoscopic retrograde cholangiography.

METHODS: A PE bile duct was characterized by a rigid and relatively narrowed distal CBD with retrograde dilatation of the non-PE segment. Between 2003 and 2006, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) images and chart reviews of 1213 patients with newly diagnosed CBD stones were obtained from the computer database of Therapeutic Endoscopic Center in Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. Patients with characteristic PE bile duct on ERC were identified from the database. Data of the patients as well as the safety and technical success of therapeutic ERC were collected and analyzed retrospectively.

RESULTS: A total of 30 patients with CBD stones and characteristic PE segments were enrolled in this study. The median patient age was 45 years (range, 20 to 92 years); 66.7% of the patients were men. The diameters of the widest non-PE CBD segment, the PE segment, and the largest stone were 14.3 ± 4.9 mm, 5.8 ± 1.6 mm, and 11.2 ± 4.7 mm, respectively. The length of the PE segment was 39.7 ± 15.4 mm (range, 12.3 mm to 70.9 mm). To remove the CBD stone(s) completely, mechanical lithotripsy was required in 25 (83.3%) patients even though the stone size was not as large as were the difficult stones that have been described in the literature. The stone size and stone/PE segment diameter ratio were associated with the need for lithotripsy. Post-ERC complications occurred in 4 cases: pancreatitis in 1, cholangitis in 2, and an impacted Dormia basket with cholangitis in 1. Two (6.7%) of the 28 patients developed recurrent CBD stones at follow-up (50 ± 14 mo) and were successfully managed with therapeutic ERC.

CONCLUSION: Patients with a PE duct frequently require mechanical lithotripsy for stones extraction. To retrieve stones successfully and avoid complications, these patients should be identified during ERC.

- Citation: Cheng CL, Tsou YK, Lin CH, Tang JH, Hung CF, Sung KF, Lee CS, Liu NJ. Poorly expandable common bile duct with stones on endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(19): 2396-2401

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i19/2396.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i19.2396

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) with endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) and stone extraction are considered standard therapies for the treatment of common bile duct (CBD) stones[1-3]. After ES, 85% to 90% of CBD stones can be removed with a Dormia basket or balloon catheter[4,5]. However, removal of CBD stones can be challenging in certain cases, such as those involving large stones (> 15 mm), stones above strictures, and impacted stones[6]. In cases involving such difficult stones, fragmentation using mechanical lithotripsy or shock wave lithotripsy is required to facilitate stone extraction[6-8]. However, mechanical lithotripsy for extraction of CBD stones can be unsuccessful in the presence of bile duct stricture, when the size of the stone is large, and when the ratio of stone size to bile duct diameter is greater than 1[9-11]. Impaction of an extraction basket and an entrapped stone in the distal CBD may complicate stone clearance in some cases[12-14].

In contrast, anatomic abnormality of the CBD has been considered to be a contributing factor to difficult stones[15]. Kim et al[16] recently reported that complete clearance of CBD stones was technically difficult in patients with acute distal CBD angulation (≤ 135 degrees) and a short distal CBD arm (≤ 36 mm). However, the current definition of large (or difficult) CBD stone does not include the factor of distal CBD diameter[17]. In our clinical experience, we have encountered a subgroup of patients whose CBD stones were particularly difficult to extract. Further, in some cases, the extraction basket containing the entrapped stone was impacted in the bile duct if mechanical lithotripsy was not applied. The common characteristic feature of these patients was a relatively narrowed distal CBD on ERC: the distal CBD was almost normal in diameter, but it was poorly expandable (PE), as the upstream CBD was disproportionately dilated. The aim of this study was to describe the clinical and imaging features and to examine the safety and technical success of ERC in patients with both CBD stones and a PE bile duct.

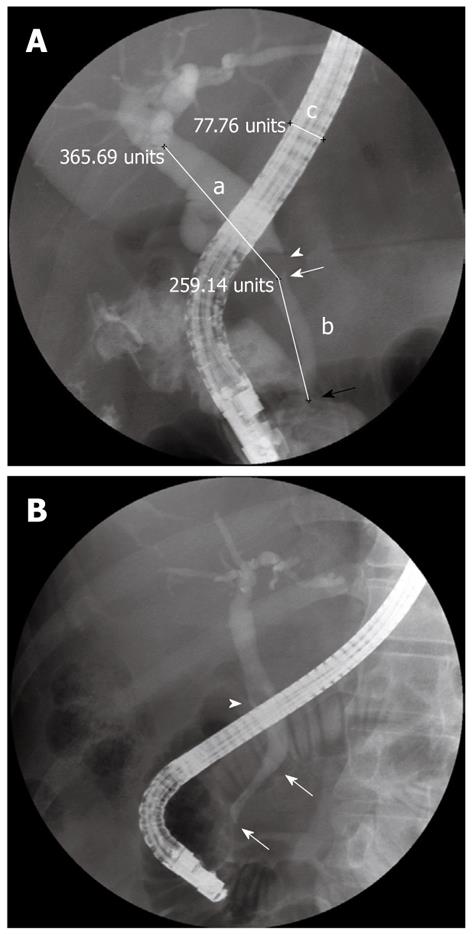

A PE bile duct was characterized by a rigid distal CBD with an almost normal diameter on ERC. The non-PE segment of CBD was often more dilated than the PE segment (Figure 1). The rigid characteristic of the PE segment was usually confirmed by increased resistance when the balloon or basket catheter with the stone was pulled from the non-PE segment across the PE segment.

During the 4-year period between 2003 and 2006, we retrospectively collected data from 1213 patients with CBD stones from the endoscopic computer database of Change Gung Memorial Hospital, Taipei (China). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) images of patients with newly diagnosed CBD stones were reviewed, and 30 (2.5%) of the patients with the characteristics of a PE bile duct were enrolled in this study. The subjects included 20 men and 10 women. The median patient age was 45 years (range, 20 to 92 years). Chart records and the safety and technical success of ERC in these patients were reviewed. None of the patients had a medical history of chronic pancreatitis or biliary stricture prior to ERCP. The clinical diagnoses were obstructive jaundice in 13 cases, acute cholangitis in 10 cases, acute cholecystitis in 3 cases, acute pancreatitis in 1 case, and others in 3 cases. The gallbladder status of the patients was as follows: previously resected in 6 (20%) cases, intact with stone(s) in 23 (76.7%) cases, and intact without stones in 1 (3.3%) case. There were 2 (6.7%) patients with low insertion of the cystic duct and 6 (20%) patients with juxtapapillary diverticulum.

Endoscopic procedures were performed by endoscopists with an ERCP case volume of at least 2 per week, using a duodenoscope (JF-240 or TJF-240; Olympus). The ES procedure was performed as mentioned in our previous study[18]. After ES, a retrieval balloon catheter (n = 9), Dormia basket (n = 5), or lithotripter (BML-202Q.B or BML-203Q.B, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan, n = 16) was used to extract the CBD stone(s). When the balloon catheter or Dormia basket failed to retrieve the stone(s), a lithotripter was used to crush and extract the stones. After stone removal, a contrast medium was injected, and the inflated balloon catheter was withdrawn along the CBD to the duodenum to confirm bile duct clearance.

The maximum transverse diameter of the PE segment, non-PE CBD, and largest stones as well as the length of PE segment and the distal CBD angle were assessed on the cholangiography. The length of the PE segment was defined as the length between the duodenal wall and the tapering end of the non-PE CBD (Figure 1). The distal CBD angle was defined as the angle between the axis of the non-PE CBD and the PE segment (Figure 1A). These factors were measured from the ERC scan, which was obtained under the condition of full contrast injection with the patient in a prone position and the duodenoscope in a shortened configuration. The parameters were measured after correction for the magnification using the known diameter of the duodenoscope on the ERC.

Data in the text and tables are expressed as the mean ± SD values. The difference in the ratio of the diameters of the non-PE segment to the PE segment and the stone size to the PE segment were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Further, the difference was compared with the two-sample t test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The analyses were performed with SPSS version 17.0 statistical software for Windows. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 30 patients with PE bile ducts who underwent a combined total of 52 ERC procedures were analyzed. The baseline characteristics of these patients are listed in Table 1. The serum total bilirubin level before ERC was 6.5 ± 3.6 mg/dL (range, 0.6 to 15 mg/dL). The maximal diameter of the non-PE CBD was 14.3 ± 4.9 mm (range, 7 mm to 26 mm). The diameter and the length of the PE segment were 5.8 ± 1.6 mm (range, 4 mm to 10 mm) and 39.7 ± 15.4 mm (range, 12.3 mm to 70.9 mm), respectively. The distal CBD angle was 159.3 ± 13.9 degree (range, 130 degree to 175 degree). The number of stones was one in 18 cases, two in 4 cases, three in 7 cases, and five in 1 case. The average diameter of the largest stone from each case was 11.3 ± 4.7 mm (range, 6 mm to 24 mm). Five patients had stones > 15 mm in diameter. Cholesterol stones were found in 16 cases, black stones in 11 cases, and brown stones in 3 cases. The ratio of the maximal diameter of the non-PE CBD to the PE segment was 2.4 (range, 1.4 to 3.5). The ratio of the diameter of the largest stone to the PE segment was 1.8 (range, 0.9 to 4).

| Parameters | Overall (n = 30) | Need lithotripsy (n = 25) | Without lithotripsy (n = 5) | 1P value |

| Age (yr) | 47.4 ± 19.4 (20-92) | 45.0 ± 19.3 (20-92) | 59.0 ± 19.4 (29-76) | 0.15 |

| Gender (men) n (%) | 20 (66.7) | 17 (68) | 3 (60) | 1 |

| Serum total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 6.5 ± 3.6 (0.6-15) | 6.7 ± 3.8 (1.1-15) | 5.5 ± 3.6 (0.6-10.1) | 0.55 |

| History of cholecystectomy n (%) | 6 (20) | 5 (20) | 1 (20) | 1 |

| Juxtapapillary diverticulum n (%) | 7 (23.3) | 5 (20) | 2 (40) | 0.57 |

| CBD stones | ||||

| Size of the largest stone (mm) | 11.3 ± 4.7 (6-24) | 12.0 ± 4.8 (6-24) | 7.2 ± 1.6 (6-10) | 0.04 |

| Characteristic (cholesterol/black/brown) | 16/11/3 | 13/9/3 | 3/2/0 | 0.72 |

| Number (≥ 2) n (%) | 12 (40) | 11 (44) | 1 (20) | 0.62 |

| Bile duct diameter (mm) | ||||

| Non-PE CBD | 14.3 ± 4.9 (7-26) | 14.8 ± 4.9 (7-26) | 11.4 ± 5.0 (7-20) | 0.17 |

| PE segment | 5.8 ± 1.6 (4-10) | 5.9 ± 1.6 (4-10) | 5.6 ± 1.8 (4-8) | 0.73 |

| Length of the PE segment (mm) | 39.7 ± 15.4 (12.3-70.9) | 38.0 ± 14.8 (12.3-70.9) | 45.1 ± 17.5 (22.5-70.2) | 0.44 |

| Distal CBD angle (degree) | 159.3 ± 13.9 (130-175) | 160 ± 12.1 (135-175) | 157 ± 18.9 (130-175) | 0.75 |

| Diameter ratio of non-PE segment to PE segment | 2.4 ± 0.6 (1.4-3.5) | 2.5 ± 0.6 (1.5-3.5) | 2.2 ± 0.4 (1.4-2.5) | 0.05 |

| Stone to PE segment | 1.8 ± 0.7 (0.9-4) | 2.1 ± 0.7 (1.2-4) | 1.4 ± 0.4 (0.9-1.8) | 0.02 |

In all patients, the CBD stones were eventually retrieved successfully. The number of ERC procedures needed to completely remove the CBD stone(s) was one in 16 (53.3%) cases, two in 8 (26.7%) cases, three in 5 (16.7%) cases, and five in 1 (3.3%) case. The reasons for performing more than one ERC procedure to completely extract the CBD stones were as follows: incomplete clearance of the CBD stones during the first ERC procedure (n = 8), referral from other institutions due to failure to extract the CBD stones (n = 3), recurrent CBD stones due to migration of the cystic duct stones (n = 2), and occurrence of Mirizzi syndrome (n = 1).

Overall, mechanical lithotripsy was performed in 25 (83.3%) patients, including 12 out of the 16 patients undergoing a single session of ERC and 13 out of the 14 patients undergoing multiple (≥ 2) sessions of ERC (4 of the 13 patients did not undergo lithotripsy during the first ERC procedure). Five patients did not require mechanical lithotripsy. Comparative data for the patients with and without lithotripsy for CBD stone clearance are given in Table 1. The factors used for analysis were age; gender; total serum level of bilirubin; stone size, number, and characteristics; history of cholecystectomy; presence of juxtapapillary diverticulum; diameter of the non-PE segment and the PE segment; length of the PE segment; distal CBD angle; and the diameter ratio of the non-PE segment to the PE segment and of the stone to the PE segment. Of the various factors analyzed, the stone size and the ratio of the diameter of the stone to the PE segment were significantly greater in patients who needed lithotripsy (P = 0.04 and 0.02, respectively).

Post-ERC complications occurred in 4 (13.3%) cases, including pancreatitis in 1 (3.3%), cholangitis in 2 (6.7%), and impacted Dormia basket with cholangitis in 1 (3.3%). One patient died of acute myocardial infarction 2 d after ERCP. Twenty-eight patients had long-term follow-up with a mean period of 50 ± 14 mo (range, 29 mo to 80 mo). Two (6.7%) patients developed recurrent CBD stones and were successfully managed with therapeutic ERC.

In this study, we describe the ERC findings of patients with concomitant CBD stones and a PE bile duct and the impact of these findings on the retrieval of the stones. This series showed that 2.5% of patients with CBD stones had PE bile ducts. The mean diameter and length of the PE duct were 5.8 mm and 39.7 mm, respectively. The non-PE CBD was more dilated than the PE segment, with a mean diameter ratio of 2.4. Post-ERC complications occurred in 4 (13.3%) of the patients.

After ES, CBD stones up to 15 mm in diameter can usually be completely extracted with a basket or a retrieval balloon catheter[8,15]. In this study, the average diameter of the largest CBD stones was 11.3 mm, and there were only five patients (16.7%) with stones > 15 mm in diameter. However, mechanical lithotripsy was frequently performed (overall, 83.3%) to clean the CBD stones for patients with a PE bile duct. This rate was much higher compared with the rate reported in the literature (9.4% to 21.7%) for patients with CBD stones who needed lithotripsy[9,10]. In the subsequent analysis, we found that stone size or the ratio of stone size to the PE segment diameter were associated with the need of lithotripsy. Since the stones were relatively small, the major factor associated with the need of lithotripsy was the ratio of stone size to the PE segment diameter. Sharma and Jain reported that 6 of 304 patients (2%) with small CBD stones (7-9 mm) had stones extraction with mechanical lithotripsy due to a narrowed distal CBD (3-4 mm)[19]. These 6 patients might also have the PE bile duct.

The endoscopists frequently chose a lithotripter as the first tool to extract the CBD stones (16/30 or 53.3%), which might be one of the reasons for the high rate of lithotripsy in this study. This practice was adopted because of several cases in our early experience that featured an impaction of the extraction basket and an entrapped stone in the PE segment. Since then, we have often used a lithotripter rather than a Dormia basket to entrap the stone, even when the stone was small. Hence, the authors had only 1 case of biliary-basket impaction in this study. Biliary-basket impaction often occurred upstream of the PE segment. Therefore, we suggest using Conquest through the channel lithotriptor cable for emergency lithotripsy when this complication occurs. In our experience, the Soehendra lithotripter cable is more difficult to pass through the relatively narrowed PE segment.

An impacted CBD stone or a large stone (≥ 30 mm) poses a high risk of mechanical lithotripsy failure[11]. In this series, CBD stones were successfully removed in all patients for whom mechanical lithotripsy was indicated, although some patients needed more than one endoscopic session. This high success rate was probably due to the small stone size, and there was no case in which the stone was impacted in the bile duct. The non-PE segment was dilated to a greater extent than the PE segment, providing the space for the opening of the lithotripter to capture the stone(s).

Eight (26.7%) of the 30 patients had incomplete clearance of the CBD stones during the first procedure of ERC; therefore, they needed multiple sessions of ERC to clean the stones completely. There might be 2 possible reasons for performing multiple sessions. First, a high proportion of patients underwent mechanical lithotripsy. After lithotripsy, small stone fragments may be left undetected after completion of the ERC procedure with bile duct clearance[20-22]. Second, the distal end of the non-PE segment tapered abruptly at its point of attachment to the PE segment. Similar to the bile duct stricture, some stone fragments might be left in the junction of the non-PE segment and the PE segment during extraction[11].

The cause of PE bile duct remains unknown. Physiologically, the intrapancreatic CBD can be entirely free within the pancreatic capsule, or less commonly, it is partially or completely enclosed by a strip of pancreatic tissue up to 20 mm wide and 3 to 5 mm thick, i.e., the lingula pancreatic[23]. The diameter of the PE segment was 5.8 ± 1.6 mm (range, 4 mm to 10 mm), which was compatible with the reported duct widths for an intrapancreatic portion of CBD[24]. Therefore, the PE bile duct may result from an intrapancreatic CBD that is entirely enclosed by the lingula pancreatis, resulting in the rigid characteristic. However, the length of PE segment had a wide range in this study (12.3 mm to 70.9 mm; mean 39.7 mm), which was not compatible with the length of the lingula pancreatis (range, 10 mm to 25 mm)[23]. Further study may be needed to investigate the nature of the PE bile duct.

The PE bile duct might not increase the risk of the recurrence of CBD stones. Tsuchiya et al[20] reported a recurrence rate of 13.2% in patients with CBD stones during a 3-year follow-up study. In a study conducted in Taiwan, the recurrence rate of CBD stones was 18%[25]. In the present series, CBD stone recurred in 7.8% of the patients during the 3-year follow-up period. This rate is no higher than that reported in the literature.

In conclusion, PE bile duct occurred in a small proportion of patients with CBD stones. Lithotripsy or multiple ERC procedures were frequently needed in patients with a PE bile duct. To avoid the complication of biliary-basket impaction, we suggest the use of a lithotripter rather than a Dormia basket to entrap and extract the stone when a PE bile duct is noted on ERC during the initial procedure.

There were several cases in early experience that featured an impaction of the extraction basket and an entrapped stone in the distal common bile duct (CBD) rather than in the papillary orifice after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Since then, the authors found that the common characteristic of these patients was a poorly expandable (PE) distal CBD on endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC). Therefore, the authors conducted this study to describe the ERC findings of patients with CBD stones and a PE bile duct and evaluate the impact of these findings on the retrieval of the stones.

CBD stones in the PE bile duct have not been reported in the literature. To the knowledge, this is the first study to describe the clinical and imaging features and to examine the safety and technical success of ERC in patients with both CBD stones and a PE bile duct.

The study showed that the diameters of the PE segment and the widest non-PE CBD segment were 5.8 ± 1.6 mm and 14.3 ± 4.9 mm, respectively. The length of the PE segment was 39.7 ± 15.4 mm (range, 12.3 mm to 70.9 mm). To remove the CBD stone(s) completely, mechanical lithotripsy was required in 83.3% of the patients, even though the stone size was not as large (11.2 ± 4.7 mm). The stone size and stone/PE segment diameter ratio were associated with the need for lithotripsy.

Patients with CBD stones and a PE duct frequently require mechanical lithotripsy during therapeutic ERC, especially when the ratio of the stone diameter to the PE segment diameter is high. To achieve successful stone retrieval and avoid complications, the authors suggest the use of a lithotripter rather than a Dormia basket to entrap and extract the stone when a PE bile duct is noted on ERC during the initial procedure.

A PE bile duct was characterized by a rigid distal CBD with an almost normal diameter on ERC. The non-PE segment of CBD was often more dilated than the PE segment. The rigid characteristic of the PE segment was usually confirmed by increased resistance when the balloon or basket catheter with the stone was pulled from the non-PE segment across the PE segment.

The authors have performed a study in which they identified all patients with CBD stones and a poorly expandable bile duct by means of a retrospective search in a computerized database. A total of 30 patients were found and the authors attempted to describe their characteristics. They concluded that the majority of these patients needed mechanical lithotripsy, especially those with a high ratio of stone diameter to the poorly-expandable CBD segment diameter. This a well-written paper and an interesting contribution to the understanding of factors related to difficult CBD stone extraction.

Peer reviewers: Evangelos Kalaitzakis, Associate professor, Institue of Internal Medicine, Sahgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, MagTarm lab, Bla straket 3, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, 41345 Gothenburg, Sweden; Jon Arne Soreide, Professor, Department of Surgery, Stavanger University Hospital, N-4068 Stavanger, Norway; Thiruvengadam Muniraj, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, 11123 Avalon Gates, Trumbull, CT 06611, United States

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Williams EJ, Green J, Beckingham I, Parks R, Martin D, Lombard M. Guidelines on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2008;57:1004-1021. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Cash BD, Fisher L, Harrison ME, Fanelli RD, Fukami N. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1-9. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Kawai K, Akasaka Y, Murakami K, Tada M, Koli Y. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1974;20:148-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cotton PB. Non-operative removal of bile duct stones by duodenoscopic sphincterotomy. Br J Surg. 1980;67:1-5. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Yoo KS, Lehman GA. Endoscopic management of biliary ductal stones. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:209-227. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Binmoeller KF, Schafer TW. Endoscopic management of bile duct stones. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:106-118. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Adler DG, Conway JD, Farraye FA, Kantsevoy SV, Kaul V, Kethu SR, Kwon RS, Mamula P, Pedrosa MC, Rodriguez SA. Biliary and pancreatic stone extraction devices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:603-609. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Muratori R, Azzaroli F, Buonfiglioli F, Alessandrelli F, Cecinato P, Mazzella G, Roda E. ESWL for difficult bile duct stones: a 15-year single centre experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4159-4163. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Garg PK, Tandon RK, Ahuja V, Makharia GK, Batra Y. Predictors of unsuccessful mechanical lithotripsy and endoscopic clearance of large bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:601-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cipolletta L, Costamagna G, Bianco MA, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Mutignani M, Marmo R. Endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy of difficult common bile duct stones. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1407-1409. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lee SH, Park JK, Yoon WJ, Lee JK, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Yoon YB. How to predict the outcome of endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy in patients with difficult bile duct stones? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1006-1010. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Attila T, May GR, Kortan P. Nonsurgical management of an impacted mechanical lithotriptor with fractured traction wires: endoscopic intracorporeal electrohydraulic shock wave lithotripsy followed by extra-endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:699-702. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Schreurs WH, Juttmann JR, Stuifbergen WN, Oostvogel HJ, van Vroonhoven TJ. Management of common bile duct stones: selective endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and endoscopic sphincterotomy: short- and long-term results. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1068-1072. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sauter G, Sackmann M, Holl J, Pauletzki J, Sauerbruch T, Paumgartner G. Dormia baskets impacted in the bile duct: release by extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1995;27:384-387. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Lauri A, Horton RC, Davidson BR, Burroughs AK, Dooley JS. Endoscopic extraction of bile duct stones: management related to stone size. Gut. 1993;34:1718-1721. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kim HJ, Choi HS, Park JH, Park DI, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI, Choi SH. Factors influencing the technical difficulty of endoscopic clearance of bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1154-1160. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Maple JT, Ikenberry SO, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Decker GA, Early D, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, Fisher D, Fisher L. The role of endoscopy in the management of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:731-744. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Tsou YK, Lin CH, Liu NJ, Tang JH, Sung KF, Cheng CL, Lee CS. Treating delayed endoscopic sphincterotomy-induced bleeding: epinephrine injection with or without thermotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4823-4828. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Sharma SS, Jain P. Should we redefine large common bile duct stone? World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:651-652. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tsuchiya S, Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y, Sugiyama H, Miyagawa K, Fukuda Y, Ando T, Saisho H, Yokosuka O. Clinical utility of intraductal US to decrease early recurrence rate of common bile duct stones after endoscopic papillotomy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1590-1595. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Ando T, Tsuyuguchi T, Okugawa T, Saito M, Ishihara T, Yamaguchi T, Saisho H. Risk factors for recurrent bile duct stones after endoscopic papillotomy. Gut. 2003;52:116-121. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Saito M, Tsuyuguchi T, Yamaguchi T, Ishihara T, Saisho H. Long-term outcome of endoscopic papillotomy for choledocholithiasis with cholecystolithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:540-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gallbladder and Bile ducts. In: Kremer K, Lierse W, Platzer W, Schreiber HW, Weller S, Steichen FM, editors. Atlas of Operative Surgery. Stuttgart, New York: Georg Thieme Verlag 1992; 44. |

| 24. | Lasser RB, Silvis SE, Vennes JA. The normal cholangiogram. Am J Dig Dis. 1978;23:586-590. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Lai KH, Lo GH, Lin CK, Hsu PI, Chan HH, Cheng JS, Wang EM. Do patients with recurrent choledocholithiasis after endoscopic sphincterotomy benefit from regular follow-up? Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:523-526. [PubMed] |