Published online May 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2145

Revised: February 7, 2012

Accepted: March 9, 2012

Published online: May 7, 2012

Small intestinal hemolymphangioma is a very rare benign tumor. There was only one report of a hemolymphangioma of the pancreas invading to the duodenum until March 2011. Here we describe the first case of small intestinal hemolymphangioma with bleeding in a 57-year-old woman. She presented with persistent gastrointestinal bleeding and endoscopy revealed a small intestinal tumor. Partial resection of the small intestine was thus performed and the final pathological diagnosis was hemolymphangioma. We also highlight the difficultly in making an accurate preoperative diagnosis in spite of modern imaging techniques. To arrive at a definitive diagnosis and exclude malignancy, partial resection of the small intestine was considered to be the required treatment.

- Citation: Fang YF, Qiu LF, Du Y, Jiang ZN, Gao M. Small intestinal hemolymphangioma with bleeding: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(17): 2145-2146

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i17/2145.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2145

Hemolymphangiomas are rare benign tumors that appear to arise from congenital malformations of the vascular system. The formation of these tumors may be explained by obstruction of venolymphatic communication, dysembrioplastic vascular tissue and systemic circulation[1]. Hemolymphangiomas most commonly present as cystic or cavernous lesions.

Herein, we report a case of hemolymphangioma of the small intestine with bleeding.

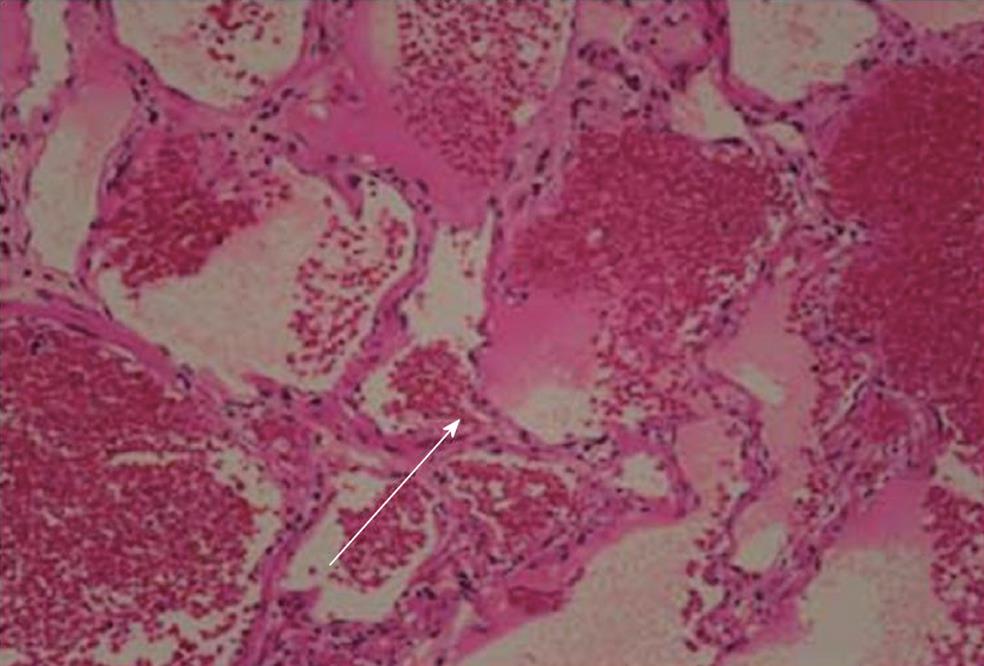

The patient was a 57-year-old woman who complained of recurrent melena for more than 2 mo. The complete blood count showed severe anemia, and stool occult blood (OB) was positive. Gastroscopy showed chronic superficial gastritis with erosion and duodenal erosion. Enteroscopy showed a gray mass with ulcers and erosion in the small intestine 30 cm distal to the flexor tendon. The mass was ill-defined, and the size was approximately 5.0 cm × 4.0 cm (Figure 1). Pathological analysis showed an intrinsic layer of dilated lymphatic vessels, a small amount of interstitial neutrophil, eosinophil, plasma cell infiltration. After admission, the stool OB continued to be positive, and the anemia was not corrected. Partial resection of the small intestine was thus performed. The small intestinal tumor was soft, and the final pathological diagnosis was a hemolymphangioma (Figure 2). The patient was discharged 7 d after the successful surgical resection of the tumor. At the annual follow-up, no recurrence was observed, and the patient is currently enjoying normal life.

Lymphangiomas are a heterogeneous group of vascular malformations that are composed of cystically dilated lymphatics. These malformations can occur at any age and may involve any part of the body; however, 90% occur in children who are less than 2 years of age and involve the head and neck. These lesions are rarely found in adult patients. Those benign malformations are classified into four categories[2]: Capillary lymphangioma, cavernous lymphangioma, cystic lymphangioma (hygroma) and hemolymphangioma (a combination of hemangioma and lymphangioma).

The incidence of hemolymphangiomas varies from 1.2 to 2.8 per 1000 newborns[3], and both genders are equally affected. The diagnosis in most cases (90%) is made before the age of two[4], 60% of those patients display symptoms at the time of birth. Hemolymphangioma of the small intestine is an uncommon and benign tumor. In a literature review of studies published until March, 2011 (PubMed), there was only one report of a hemolymphangioma of the pancreas invading to the duodenum[4]. However, there are no reports that describe small intestinal hemolymphangioma with bleeding.

The clinical onset of hemolymphangiomas can vary from a slowly growing cyst over a period of years to an aggressively enlarging but non-invasive tumor. Their size varies based on the anatomical location and relationship to the neighboring tissues. Small tumors are usually superficial, whereas the larger ones are located in deeper layers and have a cystic texture. The most common complications are spontaneous or traumatic hemorrhage, rupture and infection. On physical examination, the tumors are usually palpated as soft and compressible masses. Histologically, hemolymphangiomas consist of blood vessels and lymphatic channels.

Surgical resection appears to be the most effective treatment for hemolymphangioma, especially when the tumor increases in size and applies pressure on the surrounding tissues. Surgeons usually perform complete removal of the tumor with the surrounding organs that may be potentially invaded, because there is a possibility of recurrence and invasion of surrounding organs[5]. The recurrence rates vary depending on the complexity of the tumors, the anatomical location and the adequacy of the excision. However, lesions that have been completely excised present 10%-27% recurrence, while 50%-100% of partially resected tumors may recur. Partial or incomplete tumor removal may also be associated with complications such as infection, fistula, and hemorrhage[6].

In conclusion, our report describes on a patient with gastrointestinal bleeding due to hemolymphangioma. Surgical resection is the most effective treatment, and the case was associated with a good prognosis. Despite its low frequency, this disease should be considered when gastrointestinal bleeding is observed.

Peer reviewers: Seng-Kee Chuah, Department of Gastro-enterology, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung University College of Medicine, 123, Ta-Pei road, Niao-Sung Hsiang, Kaohsiung 833, Taiwan, China; Fook Hong Ng, Department of Medicine, Ruttonjee Hospital, 9A Heng Sang Causeway Bay Buildling, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong, China

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Balderramo DC, Di Tada C, de Ditter AB, Mondino JC. Hemolymphangioma of the pancreas: case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 2003;27:197-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kosmidis I, Vlachou M, Koutroufinis A, Filiopoulos K. Hemolymphangioma of the lower extremities in children: two case reports. J Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Filston HC. Hemangiomas, cystic hygromas, and teratomas of the head and neck. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1994;3:147-159. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Toyoki Y, Hakamada K, Narumi S, Nara M, Kudoh D, Ishido K, Sasaki M. A case of invasive hemolymphangioma of the pancreas. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2932-2934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hancock BJ, St-Vil D, Luks FI, Di Lorenzo M, Blanchard H. Complications of lymphangiomas in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:220-224; discussion 220-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hebra A, Brown MF, McGeehin KM, Ross AJ. Mesenteric, omental, and retroperitoneal cysts in children: a clinical study of 22 cases. South Med J. 1993;86:173-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |