Published online May 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2092

Revised: August 14, 2011

Accepted: September 28, 2011

Published online: May 7, 2012

AIM: To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed bowel preparation method for colon capsule endoscopy.

METHODS: A pilot, multicenter, randomized controlled trial compared our proposed “reduced volume method” (group A) with the “conventional volume method” (group B) preparation regimens. Group A did not drink polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution (PEG-ELS) the day before the capsule procedure, while group B drank 2 L. During the procedure day, groups A and B drank 2 L and 1 L of PEG-ELS, respectively, and swallowed the colon capsule (PillCam COLON® capsule). Two hours later the first booster of 100 g magnesium citrate mixed with 900 mL water was administered to both groups, and the second booster was administered six hours post capsule ingestion as long as the capsule had not been excreted by that time. Capsule videos were reviewed for grading of cleansing level.

RESULTS: Sixty-four subjects were enrolled, with results from 60 analyzed. Groups A and B included 31 and 29 subjects, respectively. Twenty-nine (94%) subjects in group A and 25 (86%) subjects in group B had adequate bowel preparation (ns). Twenty-two (71%) of the 31 subjects in group A excreted the capsule within its battery life compared to 16 (55%) of the 29 subjects in group B (ns). Of the remaining 22 subjects whose capsules were not excreted within the battery life, all of the capsules reached the left side colon before they stopped functioning. A single adverse event was reported in one subject who had mild symptoms of nausea and vomiting one hour after starting to drink PEG-ELS, due to ingesting the PEG-ELS faster than recommended.

CONCLUSION: Our proposed reduced volume bowel preparation method for colon capsule without PEG-ELS during the days before the procedure was as effective as the conventional volume method.

- Citation: Kakugawa Y, Saito Y, Saito S, Watanabe K, Ohmiya N, Murano M, Oka S, Arakawa T, Goto H, Higuchi K, Tanaka S, Ishikawa H, Tajiri H. New reduced volume preparation regimen in colon capsule endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(17): 2092-2098

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i17/2092.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2092

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer mortality in developed countries[1,2]. In recent years, colon capsule endoscopy has received widespread attention as an emerging minimally invasive endoscopic technique that is likely to impact on colorectal examination[3-10]. It is gradually being accepted as a useful diagnostic technique, particularly in Europe. Van Gossum et al[6] evaluated the first generation PillCam colon capsule and reported that the sensitivity for detecting patients with advanced polyps was 73% regardless of colon cleansing level, increasing to 88% in the subgroup of patients having adequate bowel preparation. These results have clearly shown that colon cleanliness plays an important role in providing optimal colon visualization when using colon capsule endoscopy.

However, the most commonly used preparation method may require as much as 6 L of fluid intake over two days. Reducing the volume of fluid intake is an important consideration in increasing patient acceptance of colon capsule endoscopy. Regarding traditional colonoscopy, there have been efforts to reduce patient stress by limiting fluid intake for bowel preparation to the day of examination which has resulted in better cleansing quality compared with the conventional volume method[11,12]. With respect to colon capsule endoscopy, there is no presently published report on bowel preparation during the day of examination only.

We intended to simplify the bowel preparation method by eliminating polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution (PEG-ELS) on the day before the examination and to increase acceptance for colon capsule endoscopy. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed reduced bowel preparation method for colon capsule endoscopy in terms of colon cleanliness and colon capsule excretion rates within the capsule’s battery life.

The study was a pilot, multicenter (six medical facilities), prospective, randomized controlled trial comparing our proposed “reduced volume method” with the “conventional volume method” of bowel preparation used with colon capsule endoscopy. The subjects were recruited between October 2009 and March 2010, and included men and women between 18 and 79 years of age who were either asymptomatic healthy volunteers or symptomatic patients. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at each of the six participating medical facilities. This study was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (registration ID number: UMIN000002562). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to enrollment in the study.

Subjects were stratified according to their specific medical facility, gender, age (≥ 40 years or < 40 years), and whether they were asymptomatic or symptomatic. Subjects were randomly assigned to one of the two study groups with different PEG-ELS (Muben®; Nihon Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) administration protocols: Group A (reduced volume method) received 2 L PEG-ELS during the procedure day, before capsule ingestion; Group B (conventional volume method) received 2 L PEG-ELS on the night before the procedure day and an additional 1 L during procedure day, before capsule ingestion.

Exclusion criteria included presence of dysphagia, constipation, congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency, diabetes, digestive tract diverticulum, a history of radiotherapy, accompanying cancerous peritonitis, Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, familial adenomatous polyposis or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer; individuals taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, morphine hydrochloride or tranquilizers or having a history of allergic reaction to any of the medications planned for use in this study, a cardiac pacemaker or other implanted electromedical devices; as well as anyone currently pregnant, having had abdominal surgery, suspected of symptoms or having a history of intestinal obstruction or stenosis; and any other cases in which a doctor considered it inappropriate.

According to a four-point scale grading system assessing colon cleanliness[5], based on an assumption that the average cleansing score of groups A and B are 3.5 and 3.0 with a standard deviation of 0.70 within each group, and α error of 0.05 and β error of 0.20, the required sample size is 27 subjects per group, with a total of 54 subjects.

The bowel preparation procedure is shown in Table 1. On the day before examination, all subjects had three meals consisting of a low fiber diet using ENIMACLIN® (Glico, Osaka, Japan) and 24 mg oral sennoside prior to bedtime. Group A did not receive any PEG-ELS the night before examination, while group B received 2 L PEG-ELS at 7 p.m.

| Group A | Group B | |

| Day 1 | ||

| Three regular meals | Low fiber diet | Low fiber diet |

| Evening (7-9 pm) | - | 2 L PEG-ELS |

| Bedtime | 24 mg sennoside | 24 mg sennoside |

| Day 01 | ||

| 1st Step | 100 mL water including 1 g pronase and 2.5 g sodium bicarbonate | 100 mL water including 1 g pronase and 2.5 g sodium bicarbonate |

| 2nd Step | 15 mg mosapride | 15 mg mosapride |

| 3rd Step | 2 L PEG-ELS with 400 mg dimethicone | 1 L PEG-ELS with 400 mg dimethicone |

| 4th Step2 | Additional 300 mL PEG-ELS | Additional 300 mL PEG-ELS |

| Maximum, administered twice: Maximum dosage 600 mL | Maximum, administered twice: Maximum dosage 600 mL | |

| 0 h | Colon capsule ingestion | Colon capsule ingestion |

| 2 h (BoosterI3 ) | 50 g magnesium citrate/900 mL water | 50 g magnesium citrate/900 mL water |

| 6 h (Booster II) | 50 g magnesium citrate/900 mL water | 50 g magnesium citrate/900 mL water |

| 7 h | 5 mg mosapride | 5 mg mosapride |

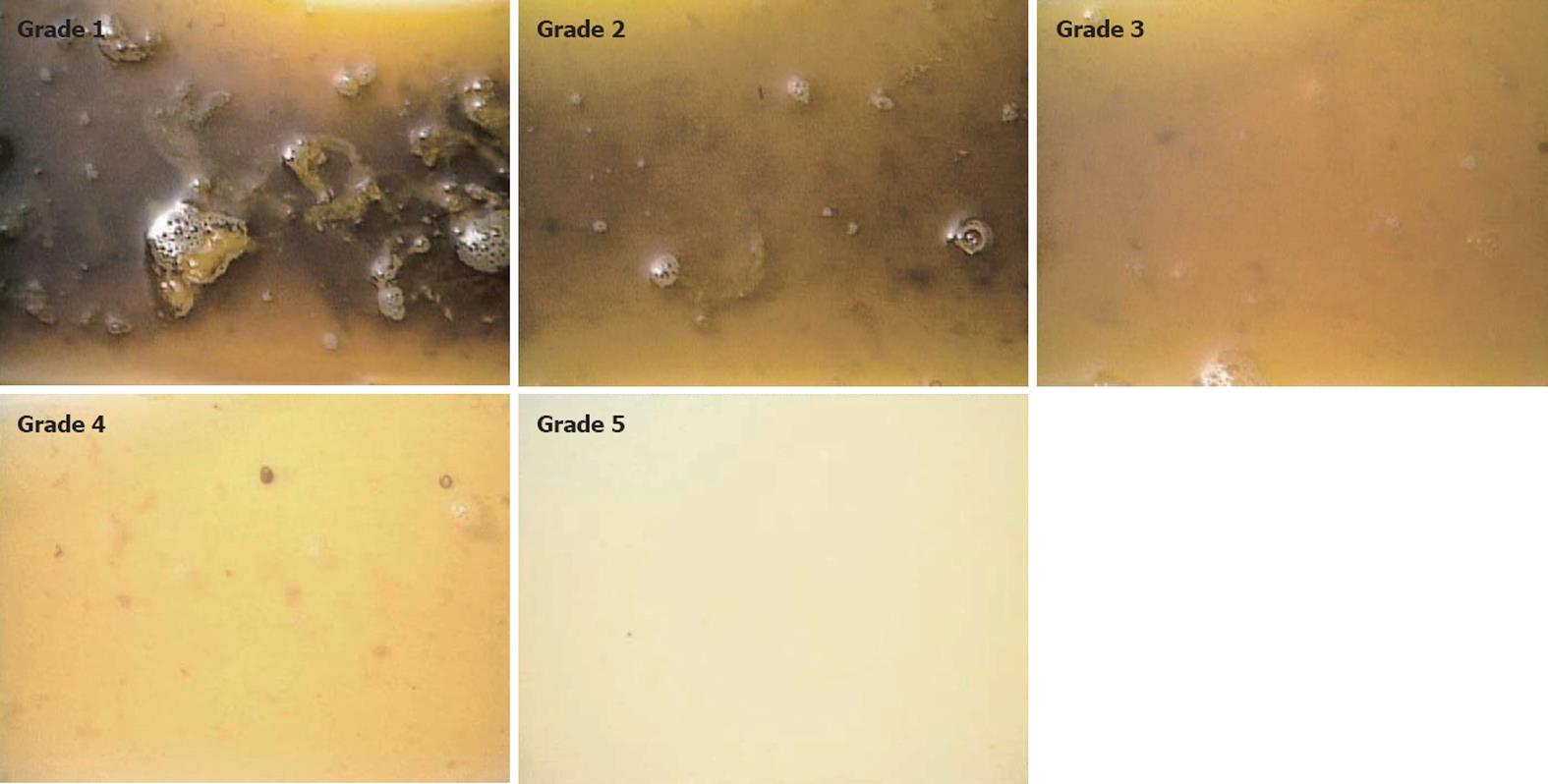

On the day of examination, all subjects drank 100 mL water which contained 1 g pronase and 2.5 g sodium bicarbonate followed by 15 mg mosapride. Then, group A subjects drank 2 L PEG-ELS with 400 mg dimethicone over 2 h, while group B subjects drank 1 L PEG-ELS with 400 mg dimethicone over 1 h. Experienced medical staff assessed the quality of the bowel preparation by checking the clarity of subjects’ evacuation before the subjects were given the colon capsule. A reference which we use to evaluate the quality of bowel preparation as a standard procedure of total colonoscopic examination in our facilities is outlined in Figure 1. Using this reference, we define that the capsule is ready to be ingested when a grade 5 quality is achieved.

In cases of unsatisfactory preparation, additional amounts of PEG-ELS (maximum total dosage, 0.6 L) were administered prior to capsule ingestion (Table 1).

When bowel preparation was judged to be complete, each subject ingested the first generation colon capsule (PillCam colon capsule, Given Imaging Inc., Yoqneam, Israel). Two hours later, the capsule location was checked with a real-time viewing monitor (RAPID® Access Real Time Tablet PC; Given Imaging). If the capsule had passed through the stomach, the subject received the first booster consisting of 50 g magnesium citrate (Magcorol P®, Horii Pharmacological Co. Ltd, Osaka, Japan) in 900 mL water in which 200 mg dimethicone was dissolved. If the capsule was in the stomach, the subjects received 5 mg mosapride as a prokinetic agent every 15 min until the capsule passed through the stomach or up to a maximum mosapride dosage of 15 mg. If the capsule was not excreted by 6 h after ingestion, subjects received a second booster similar to the first booster.

If the capsule was not excreted by 7 h after ingestion, subjects ingested 5 mg mosapride and were then permitted to eat dinner. Defecation should have been completed within eight hours so a suppository of 10 mg bisacodyl was administered to those subjects who had not excreted the colon capsule within that timeframe.

The study employed a first generation PillCam COLON capsule, and the examinations were conducted without colon intubation and insufflations or sedation. The capsule enabled recording of images for 3 min after activation, then became inactive for 1 h 45 min (sleep mode) to save battery energy. After the capsule reactivated (“woke up”), its normal operational time was approximately 6-8 h depending on the capsule’s actual battery life.

Overall colon cleanliness was determined in accordance with a four-point grading scale consisting of excellent (no more than small bits of adherent feces), good (small amount of feces or dark fluid not interfering with the examination), fair (enough feces or dark fluid present to prevent a reliable examination) and poor (large amount of fecal residue precluding a complete examination) based on previously published reports[3,4,6]. Excellent or good grades were categorized as adequate cleansing, and fair or poor as inadequate. We also scored colon cleanliness using a four-point scale grading system from 1 to 4 (excellent, good, fair and poor)[5].

Excretion of the capsule was defined as occurring when the capsule was either expelled from the subject’s body or had reached and visualized the hemorrhoidal plexus within the capsule’s battery life. Location within the colon was determined using both colorectal images and the rapid localization system.

Before commencing this study, the 20 principal investigators received two half-days of training on managing the colon capsule endoscopy examination with particular emphasis on estimation of colon cleanliness levels and procedure completion. Three selected clinicians (Kakugawa Y, Saito S and Watanabe K) who were blinded to the study groups graded the cleanliness levels. An additional independent physician (Saito Y) supervised the blinding process.

All subjects were interviewed for any associated adverse symptoms at the outpatient clinic following the colon capsule endoscopy. Adverse events were recorded as mild, moderate or severe by the physicians who performed the colon capsule procedures. A condition not requiring treatment was defined as mild, a condition needing any kind of treatment was regarded as moderate, and a condition that required any emergency treatment was considered severe.

Univariate analysis using Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare differences in colon cleansing level and capsule excretion rate between the two groups. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Sixty-four subjects enrolled in this study. Thirty-three subjects were randomly assigned to group A and 31 to group B. The colon capsules failed to “wake up” in 2 subjects of group A and 2 subjects in group B. As a result, 31 subjects in group A and 29 subjects in group B were included in our analysis (Table 2). All subjects consumed the specified initial amount of PEG-ELS. In four subjects, the quality of the bowel preparation by checking the clarity of subjects’ evacuation was not adequate prior to capsule ingestion, so an additional 0.3 L of PEG-ELS was prescribed prior to capsule ingestion for one subject in group A and 3 subjects in group B. Median fluid solution intake including boosts was 3.8 L (range, 2.9-4.1 L) in group A, while it was 4.8 L (range, 3.9-5.1 L) in group B.

| Group A (n = 31) | Group B (n = 29) | ||

| Median age | yr (range) | 39 (28-70) | 39 (29-78) |

| Gender | Male/female | 19/12 | 20/9 |

| Reason for referral | Symptomatic/asymptomatic | 4/27 | 4/25 |

| Standard PEG-ELS preparation before capsule ingestion | Without/with additional PEG-ELS prescription | 30/1 | 26/3 |

| Total volume amount of intake for 2 d | Median, liter (range) | 3.8 (2.9-4.1) | 4.8 (3.9-5.1) |

The colon capsule was located in the stomach of six subjects, the small bowel of 44 subjects, and the colon of 10 subjects when it “woke up” at 1 h 45 min post-ingestion. Of the latter 10 subjects, capsules were located in either the cecum (n = 9) or the ascending colon (n = 1).

Colon cleanliness is shown in Table 3. Colon cleanliness was evaluated as adequate in 29 subjects (94%) in group A, compared to 25 subjects (86%) in group B. The average scores of groups A and B were 3.60 ± 0.61 and 3.50 ± 0.72, respectively (ns). The level of colon cleanliness was evaluated to be excellent in all 4 of those subjects who were prescribed additional PEG-ELS just prior to colon capsule endoscopy.

| Group A (n = 31) | Group B (n = 29) | ||

| Colon cleansing level | |||

| Adequate | 29 (94%) | 25 (86%) | |

| Excellent | 13 | 14 | |

| Good | 16 | 11 | |

| Inadequate | 2 (6%) | 4 (14%) | |

| Fair | 2 | 4 | |

| Poor | 0 | 0 | |

In 25% of subjects (15/60) the capsule was excreted from the body within 6 h post-ingestion, in 53% (32/60) within 8 h, in 58% (35/60) within 10 h, and in 63% (38/60) within the capsule’s battery life. Twenty-two (71%) of the 31 subjects in group A excreted the capsule compared to 16 (55%) of the 29 subjects in group B (ns) (Table 4). Of the remaining 9 subjects in group A and 13 subjects in group B whose capsules were not excreted, all of the capsules were located in the left side colon when they stopped functioning.

| Group A (n = 31) | Group B (n = 29) | Total | ||

| Capsule excretion within battery life | 22/31 (71) | 16/29 (55) | 38/60 (63) | |

| According to colon cleansing level | Adequate | 21/29 (72) | 15/25 (60) | 36/54 (67) |

| Inadequate | 1/2 (50) | 1/4 (25) | 2/6 (33) | |

| According to location when capsule woke up | Stomach | 2/3 (67) | 0/3 (0) | 2/6 (33) |

| Small bowel | 16/24 (66) | 11/20 (55) | 27/44 (61) | |

| Colon | 4/4 (100) | 5/6 (83) | 9/10 (90) |

Only one subject, a 70-year-old female in group A, experienced mild symptoms of nausea and vomiting 1 h after starting to drink PEG-ELS, due to ingesting the PEG-ELS faster than recommended. She was advised to slow down the rate of ingestion for the remaining PEG-ELS and was able to continue with the colon capsule procedure. After capsule examination, the colon cleansing level was evaluated as being excellent.

This is the first study aimed at reducing the total amount of bowel preparation intake for colon capsule endoscopy procedures. While colon cleanliness is essential for optimal visualization during colon capsule endoscopy, fluid intake during bowel preparation can be as high as a total of 6 L over two days[4,6,7,9,10], an amount considered excessive for some patients. Reducing the volume of fluid intake is an important consideration in increasing patient acceptance of colon capsule endoscopy. We propose reducing the total amount of bowel preparation fluid by eliminating PEG-ELS intake on the day before the examination. Therefore, we conducted a multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled trial, comparing our proposed “reduced volume method” with the “conventional volume method” of bowel preparation for colon capsule endoscopy.

In this study, the level of cleansing was defined as adequate in 94% of group A subjects (reduced volume method), despite the elimination of drinking any PEG-ELS on the day before the examination. This result was higher than that of previous studies (52%-88%)[3-7,9]. We successfully reduced median fluid intake to 3.8 L (range, 2.9-4.1 L) using the reduced volume method compared to total fluid intake ranging from 4.5 to 6 L using the conventional volume method in previously reported studies[3-10]. These results indicate that the intake of PEG-ELS on the day of the examination promotes colon cleansing, whereas intake on the day before the examination may have very limited, if any, impact on the cleansing. A possible reason for this is that after ingesting and evacuating 2 L PEG-ELS on the day before the examination, biliary and intestinal secretion occurs (processes necessary for stool production) and the ingestion of only 1 L PEG-ELS on the day of the examination is then insufficient to clean the whole colon. Regarding total colonoscopy, in most Japanese facilities patients take 2 L PEG-ELS in the endoscopy waiting room on the day of the examination and the examination then starts when the fecal matter becomes liquid and transparent. In this way, we usually obtain an adequate preparation for performing total colonoscopy. The Japanese preparation method for total colonoscopy has evidence of achieving an adequate cleansing level[11,12]. Therefore, we believe that our proposed reduced volume method for colon capsule endoscopy is also adequate.

There has been no previously published report on the use of experienced medical staff in this respect. In this study, we established a method in which experienced medical staff assessed the quality of the bowel preparation by checking the clarity of subjects’ evacuation before the subjects were given the colon capsule (Figure 1). In cases of unsatisfactory preparation, an additional PEG-ELS was prescribed, with additional PEG-ELS required for one subject in group A and three subjects in group B. Following this additional PEG-ELS, colon cleanliness was judged as adequate in all four subjects. In most Japanese institutes, experienced medical staff assess the quality of the bowel preparation by checking the clarity of subjects’ evacuation before starting total colonoscopy. This may be one of the key points why we achieved a high cleansing level. Experienced medical endoscopy staff could also be utilized to help achieve a high level of colon cleanliness when performing colon capsule endoscopy.

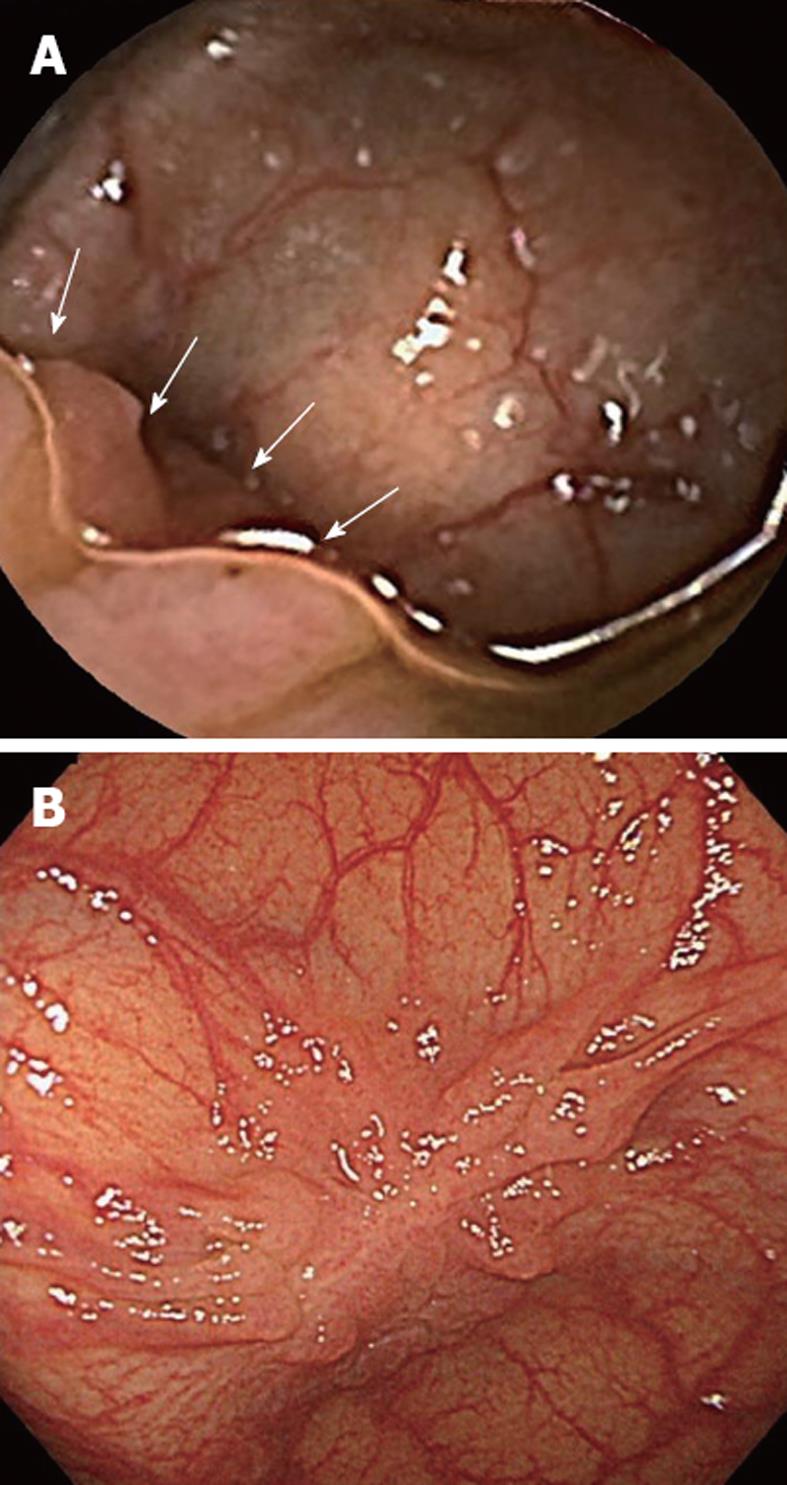

It is also important to note that small changes in technique can make significant differences in achieving a high quality of colon cleansing. The difference between this study and previous reports[3-7,9,10] is that we used pronase and dimethicone as adjuncts, and isotonic magnesium citrate as a booster. It has previously been reported that pronase was effective as a mucolytic agent[13] and dimethicone was useful in dissolving intraluminal air bubbles[14,15]. Accordingly, we used pronase dissolved into 100 mL of water as the first step on the day of examination, and dimethicone was added to the solution of PEG-ELS and magnesium citrate. We believe that dimethicone worked to join numerous microbubbles to form groups of large bubbles, resulting in better mucosal visualization, and that pronase and dimethicone should be used routinely as adjuncts to bowel preparation (Figure 2).

It is possible to conclude that our method is superior in terms of safety. Sodium phosphate has served as a booster in a number of studies[3-10], and PEG-ELS in one published report[16], but the use of magnesium citrate as a booster has not been reported. In this study, we used isotonic magnesium citrate instead of sodium phosphate as a booster, principally because it is very easy to drink since it has a similar taste to sports drinks. Japan is the only country in the world as far as we know in which isotonic magnesium citrate is available as a laxative. Secondly, isotonic magnesium citrate might reduce the level of electrolytic imbalance, while sodium phosphate has been reported as causing major problems including acute phosphate nephropathy[17,18]. Therefore, both patient acceptance and safety are increased using isotonic magnesium citrate instead of sodium phosphate as a booster.

Van Gossum et al[6] reported 6.7% adverse events related to the bowel preparation; however, in our study, a mild adverse event related to the bowel preparation was observed in only one case (3%). Moreover, this single case was then able to continue with the procedure, and the subject’s colon cleanliness level was subsequently rated as excellent. These results may indicate the higher degree of acceptance and improved safety of the reduced volume method.

Our results do not deny the cleansing ability of the conventional volume method (group B) which achieved an adequate cleansing level of 86%. There is no statistically significant difference between the two groups. However, in terms of a better quality of life and improved acceptability for patients, the reduced volume method (group A) is a preferred option for colon cleansing associated with colon capsule endoscopy.

Our proposed reduced volume method had a lower rate of capsule excretion before the battery life ended. The excretion rate was 71%, which was lower in comparison with the 64%-94% reported in previous studies[3-7,9,10]. Those reports and the present study differed in the use of bisacodyl suppository. Such use was mandatory in the earlier studies, but it was left to each individual subject in this study, with a bisacodyl suppository requested in only one case. Considering the fact that the capsule was located in the left descending colon in all cases where the capsule was not excreted within the capsule’s battery life, the use of bisacodyl suppository could have increased the excretion rate to be much higher. There may be a possibility that some subjects feel unwilling to use the suppository because of embarrassment; therefore, it may be an effective option to administer a third oral booster in order to achieve a higher excretion rate.

The size of this study was small because it was a pilot study and the median age of 39 years for all participating subjects was relatively young. Further studies are necessary to clarify the efficiency of the reduced volume method, especially in terms of increasing the excretion rate of the colon capsule. PillCam COLON2 capsule, the second generation of colon capsule, has no sleep mode and has a small bowel detection function to indicate the presence of the capsule in the small bowel[8,19]. This should allow more appropriate timing for administering the first booster, which can be expected to shorten the procedure time and improve the capsule excretion rate.

In this study, we clarified that our newly proposed regimen with a reduced volume of bowel preparation when conducting colon capsule endoscopy was as effective as the commonly used higher volume method. An important advantage of the reduced volume method is that subjects do not need to drink any PEG-ELS and can eat three low fiber meals on the day before the examination. Our proposed reduced volume bowel preparation method could be useful in encouraging subjects who have not undergone colorectal screening to undertake colon capsule endoscopy in the future.

Adequate colon cleanliness is essential for optimal visualization during colon capsule endoscopy, but the widely used preparation method may require as much as 6 L of fluid intake over two days.

The authors propose a reduced volume method without polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution intake in the days before the capsule procedure.

In this study, the authors demonstrate that a new preparation method for colon capsule endoscopy was as effective as the conventional method.

In terms of a better quality of life and improved acceptability for patients, the reduced volume method is a useful option for colon cleansing when undertaking colon capsule endoscopy.

A well conducted study on a very important issue, even if as stated by the authors "the size of this study was small because it was a pilot study".

Peer reviewer: Antonio Basoli, Professor, General Surgery “Paride Stefanini”, Università di Roma-Sapienza, Viale del Policlinico 155, 00161 Roma, Italy

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Byers T, Levin B, Rothenberger D, Dodd GD, Smith RA. American Cancer Society guidelines for screening and surveillance for early detection of colorectal polyps and cancer: update 1997. American Cancer Society Detection and Treatment Advisory Group on Colorectal Cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 1997;47:154-160. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, Godlee F, Stolar MH, Mulrow CD, Woolf SH, Glick SN, Ganiats TG, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594-642. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Eliakim R, Fireman Z, Gralnek IM, Yassin K, Waterman M, Kopelman Y, Lachter J, Koslowsky B, Adler SN. Evaluation of the PillCam Colon capsule in the detection of colonic pathology: results of the first multicenter, prospective, comparative study. Endoscopy. 2006;38:963-970. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Schoofs N, Devière J, Van Gossum A. PillCam colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy for colorectal tumor diagnosis: a prospective pilot study. Endoscopy. 2006;38:971-977. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sieg A, Friedrich K, Sieg U. Is PillCam COLON capsule endoscopy ready for colorectal cancer screening? A prospective feasibility study in a community gastroenterology practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:848-854. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Van Gossum A, Munoz-Navas M, Fernandez-Urien I, Carretero C, Gay G, Delvaux M, Lapalus MG, Ponchon T, Neuhaus H, Philipper M. Capsule endoscopy versus colonoscopy for the detection of polyps and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:264-270. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Gay G, Delvaux M, Frederic M, Fassler I. Could the colonic capsule PillCam Colon be clinically useful for selecting patients who deserve a complete colonoscopy?: results of clinical comparison with colonoscopy in the perspective of colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1076-1086. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Eliakim R, Yassin K, Niv Y, Metzger Y, Lachter J, Gal E, Sapoznikov B, Konikoff F, Leichtmann G, Fireman Z. Prospective multicenter performance evaluation of the second-generation colon capsule compared with colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1026-1031. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Sacher-Huvelin S, Coron E, Gaudric M, Planche L, Benamouzig R, Maunoury V, Filoche B, Frédéric M, Saurin JC, Subtil C. Colon capsule endoscopy vs. colonoscopy in patients at average or increased risk of colorectal cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1145-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pilz JB, Portmann S, Peter S, Beglinger C, Degen L. Colon Capsule Endoscopy compared to Conventional Colonoscopy under routine screening conditions. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chiu HM, Lin JT, Wang HP, Lee YC, Wu MS. The impact of colon preparation timing on colonoscopic detection of colorectal neoplasms--a prospective endoscopist-blinded randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2719-2725. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Parra-Blanco A, Nicolas-Perez D, Gimeno-Garcia A, Grosso B, Jimenez A, Ortega J, Quintero E. The timing of bowel preparation before colonoscopy determines the quality of cleansing, and is a significant factor contributing to the detection of flat lesions: a randomized study. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6161-6166. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Fujii T, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Hirasawa R, Uedo N, Hifumi K, Omori M. Effectiveness of premedication with pronase for improving visibility during gastroendoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:382-387. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Nouda S, Morita E, Murano M, Imoto A, Kuramoto T, Inoue T, Murano N, Toshina K, Umegaki E, Higuchi K. Usefulness of polyethylene glycol solution with dimethylpolysiloxanes for bowel preparation before capsule endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:70-74. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Bhandari P, Green S, Hamanaka H, Nakajima T, Matsuda T, Saito Y, Oda I, Gotoda T. Use of Gascon and Pronase either as a pre-endoscopic drink or as targeted endoscopic flushes to improve visibility during gastroscopy: a prospective, randomized, controlled, blinded trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:357-361. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Spada C, Riccioni ME, Hassan C, Petruzziello L, Cesaro P, Costamagna G. PillCam colon capsule endoscopy: a prospective, randomized trial comparing two regimens of preparation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, Radhakrishnan J, D'Agati VD. Acute phosphate nephropathy following oral sodium phosphate bowel purgative: an underrecognized cause of chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3389-3396. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894-909. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Spada C, Hassan C, Munoz-Navas M, Neuhaus H, Deviere J, Fockens P, Coron E, Gay G, Toth E, Riccioni ME. Second-generation colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:581-589.e1. [PubMed] |