Published online May 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2076

Revised: January 4, 2012

Accepted: February 26, 2012

Published online: May 7, 2012

AIM: To assess the role of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), age, smoking and body weight on the development of intestinal metaplasia of the gastric cardia (IMC).

METHODS: Two hundred and seventeen patients scheduled for esophagogastroduodenoscopy were enrolled in this study. Endoscopic biopsies from the esophagus, gastroesophageal junction and stomach were evaluated for inflammation, the presence of H. pylori and intestinal metaplasia. The correlation of these factors with the presence of IMC was assessed using logistic regression.

RESULTS: IMC was observed in 42% of the patients. Patient age, smoking habit and body mass index (BMI) were found as potential contributors to IMC. The risk of developing IMC can be predicted in theory by combining these factors according to the following formula: Risk of IMC = a + s - 2B where a = 2,…6 decade of age, s = 0 for non-smokers or ex-smokers, 1 for < 10 cigarettes/d, 2 for > 10 cigarettes/d and B = 0 for BMI < 25 kg/m2 (BMI < 27 kg/m2 in females), 1 for BMI > 25 kg/m2 (BMI > 27 kg/m2 in females). Among potential factors associated with IMC, H. pylori had borderline significance (P = 0.07), while GERD showed no significance.

CONCLUSION: Age, smoking and BMI are potential factors associated with IMC, while H. pylori and GERD show no significant association. IMC can be predicted in theory by logistic regression analysis.

- Citation: Felley C, Bouzourene H, VanMelle MBG, Hadengue A, Michetti P, Dorta G, Spahr L, Giostra E, Frossard JL. Age, smoking and overweight contribute to the development of intestinal metaplasia of the cardia. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(17): 2076-2083

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i17/2076.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2076

The development of gastric cancer involves an interplay of bacterial, host, and environmental facts, including dietary factors, lifestyle factors and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)[1-3]. The worldwide incidence of gastric cancer has declined over the recent decades[4]. Part of this decline is due to the recognition of risk factors such as H. pylori infection and other environmental risk factors[3,5]. Despite the overall decline in gastric cancer, there has been a significant increase in the incidence of cancer of the gastric cardia[6]. The shift from distal to proximal stomach may be due to the decrease in the distal cancers.

However, it has also been proposed that adenocarcinomas at the cardia represent a different entity of antral gastric adenocarcinomas[7]. Indeed, environmental factors or chemical carcinogens may be more strongly associated with cardia carcinomas compared with more distal gastric carcinoma[8]. On the other hand, the proximal gastric carcinomas differ from distal gastric carcinomas as they are not associated with a severe form of gastritis characterized by atrophy and/or intestinal metaplasia[9,10].

Carcinomas of the gastric cardia appear to be similar to those associated with Barrett’s esophagus, with which they share some demographic features[9]. Several studies indicated that obesity satisfies several criteria for a causal association with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and some of its complications, including erosive esophagitis, and esophageal adenocarcinoma[11-13]. Therefore, obesity could represent an important factor in the development of cardia carcinoma.

The development of cardia carcinoma seems to be preceded by intestinal metaplasia, which is secondary to chronic inflammation[1,14-16]. However, the etiology of intestinal metaplasia of the gastric cardia (IMC) remains controversial. To our knowledge, no study has evaluated the effects of age, smoking and body weight on IMC. Thus, our aim was to set up a cross-sectional study to examine these the role of these factors, and also H. pylori and GERD. To evaluate the incidence of IMC and the respective role of these factors on the development of IMC at a particular point in time, we enrolled a population of outpatients with upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy scheduled for various reasons.

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki regarding investigation in humans and was approved by our institutional Ethics committee (Commission Centrale d’Ethique) (Controlled-trials.com, Number ISRCTN15324190, http://www.controlled-trials.com). This was an investigator-initiated study with no involvement of industry.

All outpatients scheduled for an elective upper GI endoscopy were eligible for inclusion in the study. Exclusion criteria were: age < 18 years, pregnancy, patients unable to give their own consent, a previous history of upper GI surgery, severe bleeding diathesis (platelet count < 50 000/mm3, prothrombin rate < 50%), psychiatric diseases, allergy to lidocaine. All patients signed an informed consent form.

For this study, 250 consecutive patients scheduled for upper GI endoscopy for a variety of conditions were recruited over a 2.5-year period. Among them, 217 accepted the study protocol (acceptance rate of 86%). Endoscopy was performed in the left lateral position after local anesthesia using a 10% xylocaine spray with the patient under conscious sedation using midazolam as reported previously[17]. A standard endoscopy was performed, including retroflexion in the stomach (Table 1).

| Total | Men | Women | P value | OR (95% CI) | |

| No. of patients (%) | 217 | 97 (45) | 120 (55) | ||

| Age (yr) | 45.3 ± 15.3 | 49.9 ± 16.5 | 43.3 ± 13.5 | ||

| Reason for endoscopy1 | |||||

| Epigastric pain | 62 (29) | 31 | 31 | NS | |

| Barrett’s esophagus | 26 (12) | 20 | 6 | 0.01 | 4.94 (1.9-12.8) |

| Reflux grade 1 | 17 (8) | 6 | 11 | NS | |

| Reflux grade 2 | 141 (65) | 69 | 72 | NS | |

| Dyspepsia | 9 (4) | 3 | 6 | NS | |

| Dysphagia | 2 (1) | 2 | 0 | NS | |

| Gastric bypass | 48 (22) | 7 | 41 | 0.01 | 0.15 (0.06-0.35) |

| Anemia | 5 (2) | 2 | 3 | NS | |

| Celiac disease suspicion | 7 (3) | 4 | 3 | NS | |

| Ulcer follow-up | 8 (4) | 6 | 2 | NS | |

| Helicobacter antibiogram | 4 (2) | 1 | 3 | NS | |

| Personal history of reflux | 141 (65) | 69 | 72 | NS | |

| Tobacco use | |||||

| Non smoker | 119 (55) | 46 | 73 | NS | |

| Past smoker | 11 (5) | 5 | 6 | NS | |

| Current smoker all | 87 (40) | 46 | 41 | NS | |

| Current smoker 0.5 p/d | 48 (22) | 27 | 21 | NS | |

| Current smoker > 1.0 p/d | 39 (18) | 19 | 20 | NS | |

| BMI | 29.8 ± 10.6 | 32.4 ± 11.5 | 27.7 ± 7.7 | ||

| PPI users | 96 (44) | 52 | 44 | NS | |

| NSAID users | 37 (17) | 20 | 17 | NS |

Each patient had 2 biopsies performed in the esophagus 2 cm above the Z-line, 4 biopsies at the esophagogastric junction, 2 biopsies in the cardia located within 10 mm below the Z-line, 2 biopsies in the fundus (greater and lesser curvature), 2 biopsies in the antrum (greater and lesser curvature), and one biopsy in the angulus. In the case of Barrett’s esophagus, 4 biopsies were performed every cm in the Barrett’s segment. All biopsy specimens were fixed in 0.5% formaldehyde solution and stained with haematoxylin eosin, Giemsa, and Gomori-aldehyde-fuschin. Two experienced GI pathologists (BH, MB), who were blinded to the clinical diagnosis, analyzed the biopsies. The diagnosis of IMC was reserved for patients with intestinal metaplasia detected in biopsy specimens sampled from the macroscopically normal-appearing gastroesophageal junction.

As previously defined by Vakil et al[18], clinically significant GERD was diagnosed when reflux of the gastric contents caused troublesome symptoms and/or complications. It was considered negative if there were no such symptoms (Score 0), positive if the patient presented symptoms once a month (Score 1) or more than once a month (Score 2).

The presence of a hiatus hernia was defined as widening of the muscular hiatal tunnel and circumferential laxity of the phrenoesophageal membrane[19], allowing a portion of the stomach to slide into the thorax.

Smoking habit (never smoking: score 0; past smoker: score 1; current smoker < 1 pack per day: score 2; current smoker > 1 pack per day: score 3), body mass index (BMI) and age were recorded.

Endoscopic biopsies from the esophagus, the Z-line, the cardia, the fundus and the antrum were histologically evaluated for the following criteria: (1) Acute and chronic inflammation using a visual analogue scale from 0 to 3 as proposed by Dixon et al[20] in an updated Sydney system, 0 being none and 3 being marked; (2) Absence or presence of incomplete (types I, II) or complete (type III) intestinal metaplasia as defined by Filipe et al[21]; and (3) Absence or presence of H. pylori.

Barrett’s esophagus was defined as “a change in the distal esophageal epithelium of any length that can be recognized as metaplastic mucosa at endoscopy and confirmed to have intestinal metaplasia by biopsy of the tubular esophagus”[22]. Short segment Barrett’s esophagus was considered if metaplasia extended < 3 cm into the tubular esophagus or long segment Barrett’s esophagus if metaplasia extended > 3 cm into the tubular esophagus. Patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or proton pump inhibitors (PPI) during the last month before inclusion and continuously for more than 6 mo were defined as regular non steroidal antiinflammatory drug or PPI users.

The analysis of group variables was studied primarily using cross-tabulation analysis (Fischer’s exact test). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to test equality of the population. Multivariate analysis of predictors of IMC was performed by linear logistic regression. To accomplish this goal, a model was created that included all predictor variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to develop an equation to predict a logit transformation of the probability of IMC based on risk factors that included in the equation: age (years), BMI (kg/m2), smoking habit, sex, reflux disease and hiatal hernia. Age and BMI, were modeled as continuous variables, and sex was modeled as a categorical variable (0 = male and 1 = female). The final mathematical equation provided an estimate of a subject’s likelihood of having IMC. P values < 0.05 were interpreted as statistically significant. P values > 0.05 were taken as non significant (NS). SPSS advanced models 10.0 was used for statistical analysis.

A total of 217 patients were enrolled in the current study. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the group according to the sex distribution. There were no significant differences among the two groups except a higher frequency of Barrett’s esophagus in men and a higher rate of gastric bypass in women. BMI exceeded 25 kg/m2 in 54 males (56%) and 27 kg/m2 in 61 females (51%). Because our surgical team has a long lasting program of bariatric surgery[23], a substantial number of patients evaluated for gastric bypass (22%) was included but the mean BMI in the overall cohort was < 30 kg/m2. Epigastric pain and gastroesophageal reflux were the major causes for endoscopy. Of note, almost half of the patients was taking a PPI and 45% of the patients were past or current tobacco users.

Endoscopy was normal in 36% of the patients whereas erosive esophagitis and hiatus hernia were the main endoscopic findings in our population (Table 2). Barrett’s esophagus was histologically confirmed in 13% of the patients. H. pylori was present in the gastric biopsies of 70 patients (32%).

| Total | Men | Women | P value | |

| No. of patients | 217 | 97 | 120 | |

| Normal | 79 (36) | 43 | 36 | NS |

| Esophagitis1 | 26 (12) | 14 | 12 | NS |

| Hiatus hernia1 | 60 (28) | 36 | 24 | NS |

| Short segment Barrett’s | 9 (4) | 6 | 3 | NS |

| Long segment Barrett’s | 19 (9) | 11 | 8 | NS |

| Esophageal tumor | 4 (2) | 3 | 1 | NS |

| Gastric ulcer | 4 (2) | 3 | 1 | NS |

| Gastric tumor | 1 (0.5) | 1 | 0 | NS |

| Gastritis | 9 (4) | 5 | 4 | NS |

| Duodenal ulcer | 3 (1) | 2 | 1 | NS |

| Duodenal atrophy | 2 (1) | 1 | 1 | NS |

| Other | 1 (0.5) | 1 | 0 | NS |

| H. pylori | ||||

| Positive | 70 (32) | 33 | 37 | NS |

| Negative | 147 (68) | 64 | 83 | NS |

We analyzed the potential relationship between the presence of H. pylori and various factors including GERD, Barrett’s esophagus, hiatus hernia, tobacco use, sex and BMI (Table 3). There were statistically more patients infected by H. pylori with a normal esophagogastric junction (45%) than with long (16%) or short segment Barrett’s esophagus (11%) (P < 0.05). Patients with a hiatus hernia were less frequently infected by H. pylori than patients without (P < 0.05). Current tobacco users were more frequently infected by H. pylori than non or past smokers (P < 0.05).

| Total | H. pylori negative | H. pylori positive | P value | OR (95% CI) | |

| H. pylori | 217 | 147 | 70 | ||

| Reflux = 0 | 59 (27) | 36 (61) | 23 (39) | NS | |

| Reflux = 1 | 17 (8) | 11 (65) | 6 (35) | NS | |

| Reflux = 2 | 141 (65) | 100 (71) | 41 (29) | NS | |

| Short segment Barrett’s | 9 (4) | 8 (89) | 1 (11) | NS | |

| Long segment Barrett’s | 19 (9) | 16 (84) | 3 (16) | NS | |

| Normal gastroesophageal junction | 189 (87) | 122 (65) | 67 (45) | 0.01 | 4.58 (1.33-15.73) |

| Hiatus hernia | |||||

| Absent | 157 (72) | 100 (64) | 57 (36) | 0.04 | 2.06 (1.03-4.13) |

| Present | 60 (28) | 47 (78) | 13 (22) | 0.03 | 0.49 (0.24-0.98) |

| Tobacco | |||||

| Non smoker | 119 (55) | 85 (71) | 34 (29) | NS | |

| Past smoker | 11 (5) | 9 (82) | 2 (18) | NS | |

| Current smoker (all) | 87 (40) | 53 (61) | 36 (39) | 0.03 | 1.88 (1.08-3.35) |

| Current smoker 0.5 p/d | 48 (22) | 26 (54) | 22 (46) | 0.03 | 5.2 (1.1-4.12) |

| Current smoker > 1.0 p/d | 39 (18) | 27 (69) | 12 (31) | NS | |

| Age | |||||

| Mean age | 45.3 | 46.57 | 42.78 | 0.06 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 97 (45) | 64 (66) | 33 (34) | NS | |

| Female | 120 (55) | 83 (69) | 37 (31) | NS | |

| Body Mass Index | |||||

| Mean BMI | 29.8 | 30.6 | 28.1 | NS |

The correlation between the presence of reflux symptoms, and Barrett’s esophagus, hiatus hernia, tobacco use, sex, age and BMI was shown in Table 4. All patients with short segment Barrett’s esophagus and 90% of patients with long segment Barrett’s esophagus had significant reflux (P < 0.01). The presence of reflux was not statistically significantly associated with the presence of hiatus hernia or increased BMI.

| Total | Reflux | P value | |||

| Grade 0 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | |||

| No. of patients | 217 | 59 | 17 | 141 | |

| Short segment Barrett’s | 9 (4) | 1 (11) | 0 | 8 (89) | 0.010 |

| Long segment Barrett’s | 19 (9) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 17 (90) | 0.010 |

| Normal gastroesophageal junction | 189 (87) | 59 (31) | 16 (9) | 114 (60) | 0.002 |

| Hiatus hernia | |||||

| Absent | 157 (72) | 49 (31) | 13 (8) | 94 (61) | 0.060 |

| Present | 60 (28) | 10 (17) | 4 (7) | 46 (76) | NS |

| Tobacco | |||||

| Non smoker | 119 (55) | 32 (27) | 13 (11) | 74 (62) | NS |

| Past smoker | 11 (5) | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | 9 (80) | NS |

| Current smoker all | 87 (40) | 26 (29) | 11 (13) | 51 (48) | NS |

| Current smoker 0.5 p/d | 48 (22) | 14 (29) | 7 (15) | 27 (56) | NS |

| Current smoker > 1.0 p/d | 39 (18) | 12 (30) | 3 (8) | 24 (62) | NS |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 97 (45) | 22 (23) | 6 (6) | 69 (71) | NS |

| Female | 120 (55) | 37 (31) | 11 (9) | 72 (60) | NS |

| Age | |||||

| Mean age | 45.3 | 42 | 45.2 | 46.8 | 0.080 |

| Body Mass Index | |||||

| Mean BMI | 29.8 | 27.9 | 33.1 | 30.2 | 0.080 |

IMC was observed in 92 patients (42%), 48 were men and 44 were female, and the mean age was 27.3 years. IMC was not statistically associated (although there was a tendency) with the presence of H. pylori (P > 0.05), whereas H. pylori was strongly associated with the presence of inflammation of the cardia (carditis) since 82% of patients infected with H. pylori had carditis compared with 30% in the group without H. pylori infection (P < 0.001). Furthermore, there was a strong relationship between IMC and metaplasia found in other gastric areas, including the antrum and the corpus of the stomach. This relationship was not present in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. BMI was found to be significantly lower and age significantly greater in patients with IMC than in patients with normal cardia mucosa. H. pylori played a pivotal role in the development of metaplasia of the antrum and the fundus, with an odds ratio reaching 7.4 and 11.2 respectively compared with patients not infected with H. pylori (Table 5).

| Total | Intestinal metaplasia | P value | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Absent | Present | ||||

| No. of patients (%) | 217 | 125 (58) | 92 (42) | ||

| Indications for endoscopy | |||||

| GERD1 | 141 (65) | 106 (75) | 35 (25) | NS | |

| Epigastric pain1 | 62 (29) | 41 (66) | 21 (34) | NS | |

| Gastric bypass | 48 (22) | 30 (63) | 18 (37) | NS | |

| Results of endoscopy | |||||

| Normal | 79 (36) | 41 (52) | 38 (48) | NS | |

| GERD | 26 (12) | 10 (38) | 16 (62) | 0.060 | |

| Hiatus hernia | 60 (28) | 26 (43) | 34 (57) | NS | |

| Barrett's esophagus | 28 (13) | 13 (46) | 15 (54) | NS | |

| Other | 29 (13) | 17 (59) | 12 (41) | NS | |

| H. pylori | |||||

| Positive | 70 (32) | 34 (49) | 36 (51) | ||

| Negative | 147 (68) | 91 (62) | 56 (28) | 0.060 | |

| Reflux = 0 | 59 (27) | 33 (56) | 26 (44) | ||

| Reflux = 1 | 17 (8) | 15 (88) | 2 (12) | ||

| Reflux = 22 | 141 (65) | 77 (55) | 64 (45) | 0.060 | |

| BMI | 29.8 ± 10.6 | 31.61 | 27.33 | ||

| Age | 45.3 ± 15.3 | 43.29 | 50.68 | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 97 (45) | 55 (57) | 42 (43) | NS | |

| Female | 120 (55) | 70 (58) | 50 (42) | NS | |

| Tobacco use | |||||

| Non smoker | 119 | 89 | 30 | ||

| Past smoker | 11 | 8 | 3 | 0.500 | 0.6 (0.13-1.9) |

| Current smoker all | 87 | 28 | 59 | 0.001 | 6.19 (3.4-11.2) |

| Current smoker 0.5 p/d | 48 | 14 | 32 | 0.001 | 4.23 (2.1-8.5) |

| Current smoker > 1.0 p/d | 39 | 12 | 27 | 0.010 | 4.33 (2.1-9.1) |

| Antrum metaplasia | 19 | 5 | 14 | 0.010 | 4.31 (1.49-12.4) |

| Fundus metaplasia | 9 | 1 | 8 | 0.001 | 11.8 (1.45-96.1) |

GERD was not significantly associated with acute and chronic inflammation of the gastroesophageal junction, and it was not associated with the presence of IMC (borderline significance 0.06) (Table 5). Compared with patients with either short or long segment Barrett’s esophagus, patients with IMC had significantly fewer GERD symptoms.

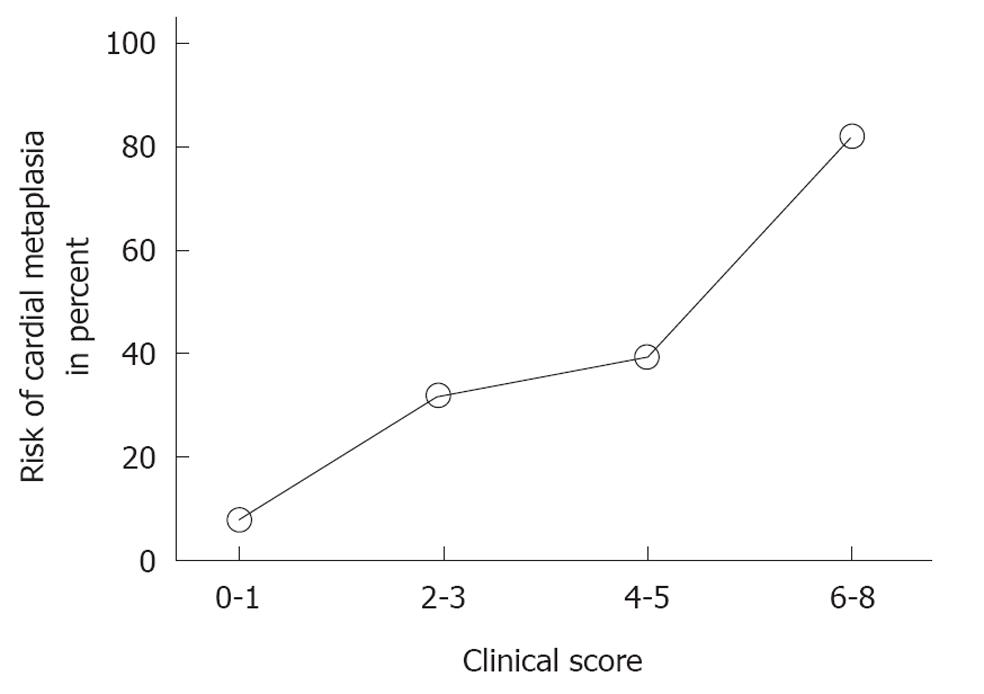

In univariate analysis, age, BMI and tobacco use were statistically significantly associated with IMC (Table 5). Using logistic regression analysis, the presence of IMC could be predicted by the patient’s age, smoking habit and the absence of overweight according to the following formula: Risk score of IMC = a + s - 2B where a = 2,…6 decade of age, s = 0 for non-smokers or ex-smokers, 1 for < 10 cigarettes per day, 2 for > 10 cigarettes per day, and B = 0 for BMI < 25 kg/m2 (BMI < 27 kg/m2), 1 for BMI > 25 kg/m2 (BMI > 27 kg/m2) for males (females), respectively. In the presence of these factors, H. pylori had only a borderline significance (P = 0.07) and would contribute only 1 point on the above scale which ranges from 0 to 8. Therefore, for a 50-year-old patient smoking 15 cigarettes per day and with a BMI of 26 kg/m2, the theoretical risk of having IMC is 5. The data of 82 patients with IMC were analyzed to obtain the actual frequency in percent of IMC as a function of the calculated risk score for a given patient using the above equation (Figure 1). Finally, the presence of H. pylori was associated with severe acute and chronic inflammation in the antrum (P < 0.01), corpus (P < 0.01) and in the Z-line area (P < 0.01).

During the last few decades there has been a marked increase in the incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction in Western countries in contrast to the reduction in incidence of distal gastric cancer. Most observers believe that this is the consequence of an increased rate of adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and a decreased incidence of distal gastric cancer related to H. pylori eradication. If the above-mentioned epidemiologic relationships are correct, this could indicate that the so-called cardia adenocarcinomas are not related to H. pylori infection but to other factors, and eventually may not be considered to be “gastric” cancers.

Because of the debated roles of different clinical factors in the emergence of malignant neoplasia of the gastric cardia, and because many reports have stated that IMC precedes the development of cardiac cancer, our study was aimed at assessing the respective roles of H. pylori, GERD, age, smoking habit and body weight on the development of IMC in a large group of patients. To this end our cross-sectional study enrolled outpatients scheduled for upper GI endoscopy for various reasons and specifically searched for the presence of IMC. The study then examined all the above mentioned variables to evaluate their respective role on the development of IMC at a particular point in time. For this purpose, each patient had endoscopic gastric and esophageal biopsies. We paid specific attention to the cardia area because the location and extent of the gastric cardia are controversial. Today, the vast majority of the data available on the cardia and cardia cancer are not comparable because of variations in the diagnostic criteria. Thus, to avoid any problem in “cardia” definition, we followed rigorous anatomist and endoscopist recommendations that defined the cardia as being the part of the stomach that lies around the orifice of the tubular esophagus, and which corresponds to the point at which the tubular esophagus joins the saccular stomach[24-26].

In our study, IMC was histologically found in 92 patients (42%). Whereas H. pylori was present in 70 patients (32%), the distribution of H. pylori was similar in patients with or without IMC, suggesting that no significant relationship between H. pylori and IMC exists. We found that H. pylori was strongly associated with the presence of carditis without IMC, as previously reported. Indeed, Sotoudeh et al[3] found a significant relationship between carditis and H. pylori infection in an Iranian cohort of patients in which the infection rate was as high as 85% whereas our infection rate was close to 32%. In contrast to our study, Goldblum et al[10] found that not only was H. pylori associated with carditis but also with IMC. In our series there was a strong correlation between the presence of H. pylori and acute or chronic inflammation in biopsies taken at different sites of the stomach. This finding is consistent with several other eastern observations showing that carditis is more associated with H. pylori infection than with GERD. In our study, GERD was present in 141 patients (65%) and was not found to be significantly associated with IMC, whereas GERD was strongly associated with acute and chronic inflammation of the gastroesophageal junction, a feature already reported by others[27,28]. Voutilainen et al[14] reported that there are two dissimilar types of chronic inflammation of the gastric cardiac mucosa that seem to occur: one existing in conjunction with chronic H. pylori infection and the other with normal stomach and erosive GERD. Patients with IMC also had significantly higher rates of metaplasia of other gastric areas. Therefore finding antral or corporeal metaplasia should alert the gastroenterologist to redo a biopsy of the cardia in a subsequent endoscopy. The absence of any correlation between the presence of IMC and Barrett’s esophagus might indicate that IMC is a distinct entity from Barrett’s esophagus as proposed by Golblum[16]. Similar inflammation and mucosal alteration in the antrum and the corpus should be regarded as a potential sign of predisposition to IMC. We found that the risk of having IMC was associated with increasing age since 70.5% of patients with IMC were > 40 years old, a feature also reported by McNamara et al[29] in a cohort of 36 patients with IMC. Among other factors associated with IMC, tobacco use was found to be strongly associated with the development of IMC and 68% of patients with IMC were smokers, data never reported before, to our knowledge. Indeed, Koizumi et al[5] reported an increased risk of IMC of 1.84 (1.39-2.43 95% CI) only for antral cancer in current smokers compared with subjects who had never smoked. BMI was surprisingly found to be a protective factor: the greater the BMI the less it contributed to the risk of IMC. This specific point should be balanced by the fact that the majority of our population was under the threshold of obesity. This finding could seem controversial against the current literature that suggests a link between obesity, GERD and carcinoma[30].

Although a real prospective study design is needed to assess a prediction, our statistician has tried to find the best fitting model to describe the relationship between the presence of IMC and various predisposing factors. The final mathematical equation provided an evaluation (and not the risk) of a subject’s likelihood of having IMC. In the current study, the presence of IMC could be predicted by age, smoking habit and low or normal BMI. The evaluation showed no association with GERD. H. pylori had only a borderline significance (P = 0.07) if any. Nevertheless, this point must be emphasized because recent studies have found two types of cardia cancer, one linked to H. pylori-associated atrophic gastritis, and the other associated with nonatrophic gastritis, resembling esophageal adenocarcinoma[7].

Although our study was not prospective, it gives results at a particular point in time, and points out the greater need for endoscopic surveillance of gastric cardia mucosal changes in individuals aged 40 and over. Regarding the epidemiology of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction, the patterns of each disease are sufficiently alike to implicate shared risk factors or even to represent a single neoplastic entity. Although studies at the molecular level have produced conflicting results, many have demonstrated the similarity between adenocarcinomas of the cardia and esophagus. Most important is the evidence that the overall survival is similar in patients with gastroesophageal junction and esophageal adenocarcinoma.

In summary, this study indicates that chronically inflamed gastric mucosa in the cardia area can be replaced by intestinal metaplasia, a finding which has been shown to precede the development of cardia cancer. Whereas esophageal adenocarcinomas are strongly associated with GERD and obesity and are inversely associated with

H. pylori, we suggest that IMC is not convincingly associated with GERD, is inversely correlated with BMI and has a dubious association with the presence of H. pylori, but is associated with increased age and a smoking habit. A prospective study aimed at evaluating the true incidence and natural history of IMC is therefore clearly needed.

Development of carcinoma of the cardia seems to be preceded by intestinal metaplasia. Gastroesophageal reflux and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection are together believed to cause intestinal metaplasia of the cardia (IMC).

Despite the overall decline in gastric cancer, there has been a significant increase in the incidence of cancer of the gastric cardia. Because the roles of different clinical factors in the emergence of cardia malignancy are still debated, there is a need to carry out further studies aiming at defining the risk factors for developing IMC.

This cross-sectional study indicated that IMC is associated with increased age and smoking, but is not strongly associated with H. pylori infection and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

The study indicates there is a greater need for endoscopic surveillance of gastric cardia mucosal changes in individuals aged 40 and over.

Intestinal metaplasia of the cardia represents a mucosal change of the gastric cardia that is secondary to chronic inflammation and that can be considered as a potential precursor of cancer.

The paper is a well-written manuscript with an important topic in clinical epidemiology. The authors tried to study the risk factors for intestinal metaplasia of the cardia. In addition they compared these factors with the epidemiological criteria of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. The results show that Barrett mucosa and IMC differed according their etiological factors.

Peer reviewer: Cesare Tosetti, Department of Primary Care, Health Care Agency of Bologna, via Rosselli 21, Porretta Terme (BO) 40046, Italy

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Conio M, Filiberti R, Blanchi S, Giacosa A. Carditis, intestinal metaplasia and adenocarcinoma of oesophagogastric junction. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2001;10:483-487. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Fuchs F, Poirier B, Leparc-Goffart I, Buchheit KH. Collaborative study for the establishment of the Ph. Eur. BRP batch 1 for anti-vaccinia immunoglobulin. Pharmeuropa Bio. 2005;2005:13-18. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Sotoudeh M, Derakhshan MH, Abedi-Ardakani B, Nouraie M, Yazdanbod A, Tavangar SM, Mikaeli J, Merat S, Malekzadeh R. Critical role of Helicobacter pylori in the pattern of gastritis and carditis in residents of an area with high prevalence of gastric cardia cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:27-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fitzsimmons D, Osmond C, George S, Johnson CD. Trends in stomach and pancreatic cancer incidence and mortality in England and Wales, 1951-2000. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1162-1171. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Koizumi Y, Tsubono Y, Nakaya N, Kuriyama S, Shibuya D, Matsuoka H, Tsuji I. Cigarette smoking and the risk of gastric cancer: a pooled analysis of two prospective studies in Japan. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:1049-1055. [PubMed] |

| 6. | McColl KE. Cancer of the gastric cardia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:687-696. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Hansen S, Vollset SE, Derakhshan MH, Fyfe V, Melby KK, Aase S, Jellum E, McColl KE. Two distinct aetiologies of cardia cancer; evidence from premorbid serological markers of gastric atrophy and Helicobacter pylori status. Gut. 2007;56:918-925. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ladeiras-Lopes R, Pereira AK, Nogueira A, Pinheiro-Torres T, Pinto I, Santos-Pereira R, Lunet N. Smoking and gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:689-701. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Axon AT. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori gastritis, gastric cancer and gastric acid secretion. Adv Med Sci. 2007;52:55-60. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Goldblum JR. Inflammation and intestinal metaplasia of the gastric cardia: Helicobacter pylori, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or both. Dig Dis. 2000;18:14-19. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hjartåker A, Langseth H, Weiderpass E. Obesity and diabetes epidemics: cancer repercussions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;630:72-93. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Festi D, Scaioli E, Baldi F, Vestito A, Pasqui F, Di Biase AR, Colecchia A. Body weight, lifestyle, dietary habits and gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1690-1701. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Corley DA, Kubo A, Zhao W. Abdominal obesity and the risk of esophageal and gastric cardia carcinomas. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:352-358. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Voutilainen M, Färkkilä M, Mecklin JP, Juhola M, Sipponen P. Chronic inflammation at the gastroesophageal junction (carditis) appears to be a specific finding related to Helicobacter pylori infection and gastroesophageal reflux disease. The Central Finland Endoscopy Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3175-3180. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Voutilainen M, Sipponen P. Inflammation in the cardia. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2001;3:215-218. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Goldblum JR, Vicari JJ, Falk GW, Rice TW, Peek RM, Easley K, Richter JE. Inflammation and intestinal metaplasia of the gastric cardia: the role of gastroesophageal reflux and H. pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:633-639. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Felley C, Perneger TV, Goulet I, Rouillard C, Azar-Pey N, Dorta G, Hadengue A, Frossard JL. Combined written and oral information prior to gastrointestinal endoscopy compared with oral information alone: a randomized trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:22. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kahrilas PJ, Kim HC, Pandolfino JE. Approaches to the diagnosis and grading of hiatal hernia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:601-616. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161-1181. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Filipe MI, Muñoz N, Matko I, Kato I, Pompe-Kirn V, Jutersek A, Teuchmann S, Benz M, Prijon T. Intestinal metaplasia types and the risk of gastric cancer: a cohort study in Slovenia. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:324-329. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Wang KK, Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:788-797. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Bobbioni-Harsch E, Huber O, Morel P, Chassot G, Lehmann T, Volery M, Chliamovitch E, Muggler C, Golay A. Factors influencing energy intake and body weight loss after gastric bypass. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:551-556. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Odze RD. Pathology of the gastroesophageal junction. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2005;22:256-265. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Riddell RH. The biopsy diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease, "carditis," and Barrett's esophagus, and sequelae of therapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20 Suppl 1:S31-S50. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Petersson F, Franzén LE, Borch K. Characterization of the gastric cardia in volunteers from the general population. Type of mucosa, Helicobacter pylori infection, inflammation, mucosal proliferative activity, p53 and p21 expression, and relations to gastritis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:46-53. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Pieramico O, Zanetti MV. Relationship between intestinal metaplasia of the gastro-oesophageal junction, Helicobacter pylori infection and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:567-572. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Csendes A, Smok G, Quiroz J, Burdiles P, Rojas J, Castro C, Henríquez A. Clinical, endoscopic, and functional studies in 408 patients with Barrett's esophagus, compared to 174 cases of intestinal metaplasia of the cardia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:554-560. [PubMed] |

| 29. | McNamara D, Buckley M, Crotty P, Hall W, O'Sullivan M, O'Morain C. Carditis: all Helicobacter pylori or is there a role for gastro-oesophageal reflux? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:772-777. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Balbuena L, Casson AG. Physical activity, obesity and risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Future Oncol. 2009;5:1051-1063. [PubMed] |