Published online Apr 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i16.1926

Revised: February 22, 2012

Accepted: February 26, 2012

Published online: April 28, 2012

AIM: To identify the factors associated with overall survival of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

METHODS: A total of 286 patients with HCC (male/female: 178/108, age: 46-100 years), who were diagnosed and treated by appropriate therapeutic procedures between January 2000 and December 2010, were enrolled in this study. Patients were stratified into two groups on the basis of age: Elderly (≥ 75 years old) and non-elderly (< 75 years old). Baseline clinical characteristics as well as cumulative survival rates were then compared between the two groups. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify the factors associated with prolonged overall survival of patients in each group. Cumulative survival rates in the two groups were calculated separately for each modified Japan Integrated Stage score (mJIS score) category by the Kaplan-Meier method. In addition, we compared the cumulative survival rates of elderly and non-elderly patients with good hepatic reserve capacity (≤ 2 points as per mJIS).

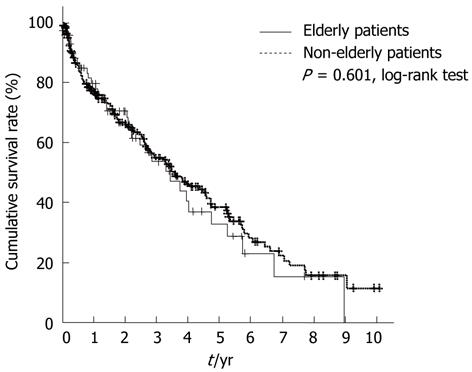

RESULTS: In the elderly group, the proportion of female patients, patients with absence of hepatitis B or hepatitis C viral infection, and patients with coexisting extrahepatic comorbid illness was higher (56.8% vs 31.1%, P < 0.001; 27.0% vs 16.0%, P = 0.038; 33.8% vs 22.2%, P = 0.047; respectively) than that in the non-elderly group. In the non-elderly group, the proportion of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected patients was higher than that in the elderly group (9.4% vs 0%, P = 0.006). The cumulative survival rates in the elderly group were 53.7% at 3 years and 32.9% at 5 years, which were equivalent to those in the non-elderly group (55.9% and 39.4%, respectively), as shown by a log-rank test (P = 0.601). In multivariate analysis, prolonged survival was significantly associated with the extent of liver damage and stage (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively), but was not associated with patient age. However, on individual evaluation of factors in both groups, stage was significantly (P < 0.001) associated with prolonged survival. Regarding mJIS scores of ≤ 2, the rate of female patients with this score was higher in the elderly group when compared to that in the non-elderly group (P = 0.012) and patients ≥ 80 years of age tended to demonstrate shortened survival.

CONCLUSION: Survival of elderly HCC patients was associated with liver damage and stage, but not age, except for patients ≥ 80 years with mJIS score ≤ 2.

- Citation: Fujii H, Itoh Y, Ohnishi N, Sakamoto M, Ohkawara T, Sawa Y, Nishida K, Ohkawara Y, Yamaguchi K, Minami M, Okanoue T. Factors associated with the overall survival of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(16): 1926-1932

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i16/1926.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i16.1926

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), one of the most common causes of mortality worldwide, usually occurs in a cirrhotic liver[1-3]. Moreover, the number of elderly HCC patients is increasing, and the average age of patients with hepatitis C is increasing in Japan[4-8]. This trend indicates the need to investigate and identify the optimal treatment of HCC in elderly patients. Elderly patients have a high incidence of comorbid illnesses and the risks of major surgery are usually higher in these patients when compared to those in younger patients. Therefore, radical surgical resection of HCC is less feasible in elderly patients than in younger patients.

Some studies have indicated that treatment outcomes in elderly patients are essentially similar to those in non-elderly patients; moreover, there are several studies comparing different treatment procedures[9-16]. However, the prognostic factors for survival in elderly patients remain obscure. This article aims to review a retrospective cohort of elderly (≥ 75 years) and non-elderly (< 75 years) patients in order to clarify the characteristics of elderly HCC patients and reveal the factors associated with prolonged survival of these patients.

A total of 286 patients with HCC treated at AiseikaiYamashinaHospital between January 2000 and December 2010 were enrolled in this study. A follow up study of patient survival was performed until the end of December 2010. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We explained our therapeutic strategy and other regimens to each patient prior to every treatment procedure and obtained written informed consent from all patients.

The 286 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were categorized into two groups as elderly (≥ 75 years) and non-elderly (< 75 years old). The breakpoint of 75 years old was chosen because it enabled comparison with other relevant reports. Moreover, in Japan, patients ≥ 75 years of age are covered by a health insurance system which is different from that of patients < 75 years.

The etiology of liver disease was classified as follows: (1) hepatitis B virus (HBV), if patients were hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive; (2) HCV, if patients were anti-HCV positive; (3) HCV and HBV, if patients were both HBsAg and anti-HCV positive; and (4) non-B non-C, if patients were negative for both HBsAg and anti-HCV.

The severity of liver damage was scored according to the Liver Damage Classification scheme proposed by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan (LCSGJ)[17].

The diagnosis of HCC was based on histopathology and/or imaging studies such as ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT) scans, angiography, CT angiography, and magnetic resonance imaging. The final diagnosis was confirmed when at least two diagnostic modalities identified the presence of HCC. The tumor stage was defined on the basis of the LCSGJ. To compare treatment outcomes with those of other institutions, the modified Japan Integrated Stage score (mJIS score) was selected as the integrated staging system for HCC[17].

After diagnosis of HCC, the most appropriate therapeutic procedure was selected according to the tumor status and underlying hepatic reserve capacity of each patient. As a general rule, we treated all patients except for those with uncontrollable ascites or hepatic encephalopathy and those who rejected any treatment. Hepatic resection (HR) was particularly considered in patients with localized HCC and preserved hepatic reserve capacity. Nonsurgical treatments, such as transcatheterarterial chemoembolization (TACE), transcatheterarterial infusionchemotherapy (TAI),percutaneous ethanol injection therapy (PEIT), radiofrequency ablation therapy (RFA), and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) were considered when the patients refused surgical treatment or HR was not feasible. TACE was performed using doxorubicin hydrochloride or cisplatin with iodized oil (Lipiodol Ultra Fluide; LaboratoireGuerbet, Roissy, France) and gelatin sponge particles. TAI was performed using doxorubicin hydrochloride or cisplatin. Locoregional ablative therapies such as PEIT and RFA were considered in patients with one to three tumor nodules that were devoid of vascular invasion and not associated with extrahepatic metastases. All locoregional ablative therapies were CT- or US-assisted. HAIC was performed using intra-arterial hepatic injections with low-dose 5-fluorouracil/cisplatin[18]. In many cases, patients were treated by a combination of several procedures. These therapies were repeated when HCC relapsed until patients reached maximum tolerability. The best supportive care was considered when the patient had compromised hepatic reserve capacity or when he/she refused any treatment for HCC.

The presence of malignant tumors other than HCC, cardiovascular diseases, renal diseases, pulmonary diseases, and neurological diseases, all of which could have potential impact on the prognosis, were recorded.

To evaluate the differences in clinical features of the patients and tumor characteristics, the Mann-Whitney U and Pearson χ2 tests were used for continuous and discrete data, respectively. The analytical data were first collected on the day of initial HCC diagnosis. The patients were followed-up as long as they lived or, in some cases, until their last visit to the hospital. The primary outcome was overall survival. Cumulative survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the logrank test. Patient survival was followed up to 31 December, 2010. For the analysis of predictors of survival, a Cox proportional hazards model was used, in which the following parameters were evaluated: age (≥ 75 years or < 75 years), gender, presence of comorbid illnesses, HCV positivity, serum alfa-fetoprotein ≥ 200 ng/mL, serum des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin ≥ 200 mAU/mL, and liver damage classification and stage. A P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 19.0 statistical package (SPSS Incorporated, Chicago, Illinois, United States).

The clinical profiles of 286 patients, divided into elderly (≥ 75 years) and non-elderly (< 75 years) groups, are shown in Table 1. In the elderly group, the number of female patients, patients with comorbid illness, and patients with absence of HBV and HCV infection (non-B non-C) were significantly higher (P < 0.001, P = 0.047, P = 0.038, respectively) than those in the non-elderly group. In the non-elderly group, the proportion of patients with HBV infection was significantly (P = 0.006) higher than that in the elderly group.

| Elderly patients (n = 74 ) | Non-elderly patients (n = 212 ) | Pvalue | |

| Age (yr) (range) | 80.5 (75.4-100.0) | 65.8 (46.0-74.8) | - |

| Male/female (%) | 32/42 (43.2/56.8) | 146/66 (68.9/31.1) | P < 0.001 |

| Extrahepaticcomorbidity (%) | 25 (33.8) | 47 (22.2) | P < 0.05 |

| Malignant tumors except HCC | 6 | 12 | |

| Cardiovascular | 10 | 15 | |

| Renal | 3 | 7 | |

| Pulmonary | 3 | 4 | |

| Neurological | 3 | 9 | |

| Cause of liver dysfunction | |||

| HBV (%) | 0 | 20 (9.4) | P < 0.01 |

| HCV (%) | 54 (73.0) | 155 (73.2) | NS |

| HBV HCV (%) | 0 | 3 (1.4) | NS |

| Non-B Non-C (%) | 20 (27.0) | 34 (16.0) | P < 0.05 |

| Liver damage A/B/C | 39/31/4 | 97/86/29 | NS |

| Stage I/II/III/IV | 13/24/23/14 | 45/71/51/45 | NS |

| mJIS score 0/1/2/3/4/5 | 9/16/22/18/8/1 | 24/53/59/36/27/13 | NS |

| Death except hepatic disease/total death | 10/35 | 18/113 | NS |

Over a median follow-up of 1.8 years, 148 patients died, of whom 35 were elderly and 113 were non-elderly patients. The median survival period was comparable in the two groups [elderly: 3.46 years, 95% confidence interval (CI), 2.26-4.66; non-elderly: 3.56 years, 95% CI, 2.58-4.55; P = 0.167] (Figure 1). The survival rates at one, three, five, and 10 years were 79.7%, 53.7%, 32.9%, and 0.0% in the elderly group, and 77.9%, 55.9%, 39.4%, and 12.4% in the non-elderly group, respectively. There were no significant differences in survival rates between the two groups (P = 0.601).

With regard to the cause of mortality, 10 patients (28.6%) in the elderly group and 18 patients (16.8%) in the non-elderly group died from causes other than hepatic diseases (tumor progression, hepatic failure, variceal bleeding, or other complications of cirrhosis), and there were no significant differences between the two groups (P = 0.095, Table 1). In addition, we performed an analysis of survival rates after excluding patients who died from causes other than hepatic diseases. As a result, the survival rates at one, three, five, and 10 years were 86.8%, 64.0%, 42.3%, and 0.0% in the elderly group, and 80.8%, 60.7%, 44.9%, and 18.6% in the non-elderly group, respectively. There were no significant differences in survival rates between the two groups (P = 0.779, data not shown).

The factors affecting survival in all patients were calculated by multivariate analysis, and liver damage and stage were selected as the significant factors (Table 2). In elderly patients, multivariate analysis demonstrated that stage was independently associated with survival. In non-elderly patients, multivariate analysis demonstrated that liver damage and stage were independently associated with survival (Table 3). Gender, comorbid illness, HCV positivity, and tumor markers were not associated with survival in both groups.

| Univariate analysis relative risk | Pvalue | Multivariate analysis relative risk | Pvalue | |

| Age ≥ 75 yr | 1.107 | NS | 1.161 | NS |

| Gender (male) | 1.155 | NS | 1.135 | NS |

| Comorbid illness | 1.335 | NS | 1.144 | NS |

| HCV+ | 0.636 | < 0.05 | 1.036 | NS |

| AFP (ng/mL) ≥ 200 | 2.098 | < 0.001 | 1.229 | NS |

| DCP (mAU/mL) ≥ 200 | 1.763 | < 0.05 | 1.229 | NS |

| Liver damage | ||||

| A/B | 2.345 | < 0.001 | 2.506 | < 0.001 |

| B/C | 7.674 | < 0.001 | 10.463 | < 0.001 |

| Stage | ||||

| I/II | 3.168 | < 0.001 | 3.126 | < 0.001 |

| II/III | 3.818 | < 0.001 | 6.323 | < 0.001 |

| III/IV | 20.064 | < 0.001 | 35.498 | < 0.001 |

| Elderly | Non-Elderly | |||

| Univariate analysisPvalue | Multivariate analysisPvalue | Univariate analysisPvalue | Multivariate analysisPvalue | |

| Gender (male) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Comorbid illness | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| HCV+ | NS | NS | < 0.05 | NS |

| AFP (ng/mL) ≥ 200 | NS | NS | < 0.001 | NS |

| DCP (mAU/mL) ≥ 200 | NS | NS | < 0.05 | NS |

| Liver damage | ||||

| A/B | NS | NS | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| B/C | < 0.001 | NS | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Stage | ||||

| I/II | NS | < 0.001 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| II/III | NS | < 0.001 | < 0.05 | < 0.001 |

| III/IV | NS | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

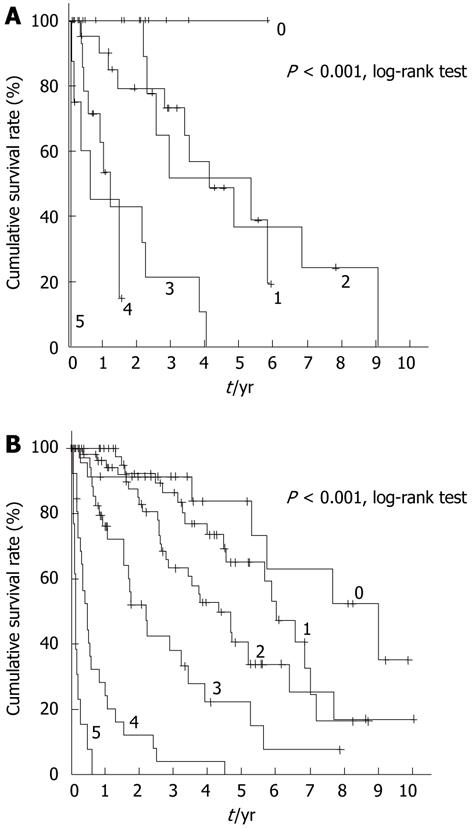

Because survival was influenced by both liver damage and stage, we applied mJIS scores to both patient groups, and reached the conclusion that there was no clear association between these scores and survival in elderly patients (Figure 2A), whereas there was a clear association between the two in non-elderly patients (Figure 2B).

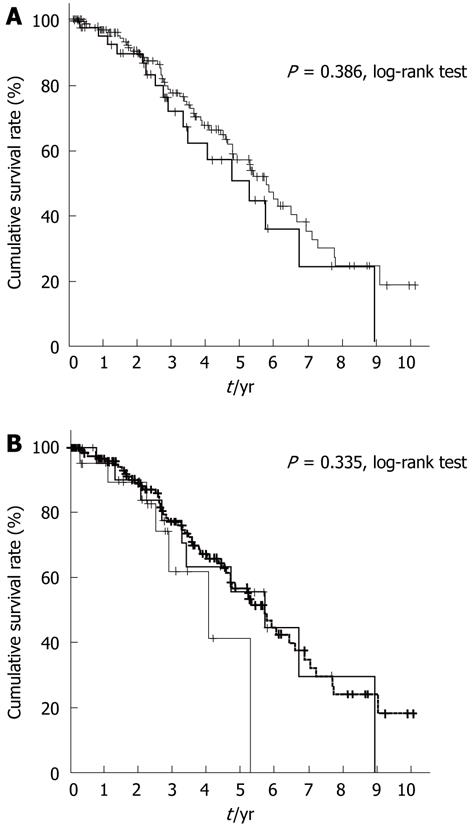

Furthermore, we analyzed the clinical profile of patients with mJIS scores of ≤ 2 in both groups (Table 4). The 5-year survival rate of these patients was expected to be ≥ 50%. In the elderly group, the proportion of females with this score was higher than that in the non-elderly group. In the non-elderly group, the proportion of patients with HBV infection was higher than that in the elderly group. Other clinical factors were not statistically different. There was no significant difference in survival rates between patients with this score in both groups (P = 0.386, Figure 3A). Furthermore, we analyzed the survival rate of elderly patients with mJIS scores ≤ 2 by dividing them into two subgroups, one comprising patients between 75 and 80 years of age and the other comprising patients ≥ 80 years of age. The survival rates tended to deteriorate in the latter group of patients, although the difference was not significantly different (P = 0.335, Figure 3B).

| Elderly patients (n = 47 ) | Non-elderly patients (n = 136 ) | Pvalue | |

| Age (yr) (range) | 80.3 (75.4-87.7) | 65.8 (46.0-74.8) | - |

| Male/female (%) | 21/26 (43.2/56.8) | 89/47 (68.9/31.1) | P < 0.05 |

| Extrahepaticcomorbidity (%) | 16 (34.0) | 33 (24.3) | NS |

| Malignant tumors except HCC | 5 | 9 | |

| Cardiovascular | 5 | 8 | |

| Renal | 2 | 4 | |

| Pulmonary | 2 | 4 | |

| Neurological | 2 | 8 | |

| Cause of liver dysfunction | |||

| HBV (%) | 0 | 11 (8.1) | P < 0.05 |

| HCV (%) | 37 (78.7) | 109 (80.1) | NS |

| HBV HCV (%) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | NS |

| non-B non-C (%) | 10 (21.3) | 14 (10.3) | NS |

| Liver damage A/B/C | 32/14/1 | 87/45/4 | NS |

| Stage I /II/ III/ IV | 13/24/10 | 45/64/27 | NS |

In this study, we reviewed HCC cases by dividing them into two groups and demonstrated that the survival rates of elderly patients ≥ 75 years of age were generally equivalent to those of non-elderly patients < 75 years of age. There have been many previous studies reporting the efficiency and safety of each treatment modality for HCC in elderly patients, and most reports have shown similar survival rates and safety when compared with those of non-elderly patients[9-16]. However, in clinical practice, HCC is treated with several modalities in Japan. A previous paper, which evaluated the total survival rates of older HCC patients in comparison with those of younger HCC patients[19-21], reported cumulative survival rates similar to those reported in our present study.

Our elderly and non-elderly HCC patients differed in several clinical characteristics. Elderly patients were more likely to be female and negative for both HBV and HCV. This was expected since all these factors are known to influence the age of HCC development. The peak age of HCC occurrence in females is 5 years later than that in males[22]. HCV infection is generally acquired during adult life[23], while HBV infection frequently occurs in childhood[24]. A multifactorial etiology accelerates the progression of chronic liver disease, hence anticipating the appearance of HCC[22,25].

Despite a higher prevalence of comorbid illnesses and a difference of 14.7 years in the mean age, elderly patients demonstrated an overall 5-year survival similar to that of their younger counterparts. This unexpected result could be because of the low survival rate of both groups (overall survival of approximately < 40% at 5 years). The Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan has reported the 5-year overall survival rate after initial HCC diagnosis as 35.4%[5]. There may be many specific factors that influence the treatment strategy for elderly patients. Aggressive and risky treatments in these patients may be avoided due to comorbid illnesses. However, the impact of HCC occurrence on life expectancy outweighs that of both comorbid illnesses and age. We suggest that comorbid conditions and therapeutic procedures (including hepatectomy) had little effect on the survival of the patients especially the elderly ones.

Before analyzing the prognostic factors in each group, it was expected that the presence of comorbid illnesses may be a poor prognostic factor for elderly patients. However, this factor was not statistically associated with survival rates in either the elderly or non-elderly patient groups. The analysis of prognostic factors revealed that liver damage and stage were significantly associated with survival rates in both groups. Furthermore, stage was a very strong factor in elderly patients. Patients who have a sufficient hepatic reserve capacity may survive long enough for HCC to develop. The association of other factors with survival in elderly HCC patients seems insignificant in comparison with that of stage.

We also analyzed patients with a good hepatic reserve capacity (≤ 2 points as per mJIS), whose 5-year survival rate was expected to exceed 50% (Figure 3A). However, there was no statistical difference between survival rates of patients ≥ 75 and < 75 years of age. Interestingly, when divided into subgroups, the survival of patients ≥ 80 years of age was shorter than that of patients in the other subgroup (Figure 3B). In other words, extreme old age influenced the survival rate even in patients with good hepatic reserve capacity.

With regard to the cause of death, there was no difference between elderly and non-elderly patients (Table 1). Similar to non-elderly patients, elderly patients also died from liver-associated diseases. If the HCC patients ≥ 80 years of age were divided into two subgroups (treated and untreated), there were obvious differences in the prognosis(data not shown). Further studies with a larger sample of patients will clarify this issue in future.

In conclusion, survival of elderly HCC patients (≥ 75 years old) was associated with liver damage and stage. The effectiveness of treatment for HCC was equivalent in elderly and non-elderly patients. Survival was unaffected by age; however, when individually evaluated for patients with a mJIS score of ≤ 2, those ≥ 80 years of age tended to demonstrate shortened survival.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), one of the most common causes of mortality worldwide, usually occurs in a cirrhotic liver. At present, the number of elderly HCC patients is increasing, as is the average age of hepatitis C is increasing in Japan. However, the factors associated with overall survival of patients with HCC especially the elderly (≥ 75 years old) are not adequately investigated.

Some studies have indicated that treatment outcomes in elderly patients are essentially similar to those in non-elderly patients. In addition, there are several studies comparing different treatment procedures. The research hotspot is to clarify general prognostic factors for survival in elderly HCC patients in Japan.

In the elderly HCC patients of Japan, the proportion of female patients, patients with absence of hepatitis B or hepatitis C viral infection, and patients with coexisting extrahepatic comorbid illness was higher than that in the non-elderly group. The cumulative survival rates in the elderly group were 53.7% at 3 years and 32.9% at 5 years, which were equivalent to those in the non-elderly group, as shown by a log-rank test. In multivariate analysis, prolonged survival was significantly associated with the extent of liver damage and stage, but was not associated with patient age. Patients ≥ 80 years of age tended to demonstrate shortened survival.

In the present study, the authors have reached the conclusion that survival of the HCC patients treated by appropriate procedures depends on liver damage and stage, but not on patient age. Only patients ≥ 80 years of age tended to demonstrate shortened survival.

The modified Japan Integrated Stage score (mJIS score) is the integrated staging system which combined the degree of liver damage and the degree of tumor stage.

This is a good descriptive study in which authors analyze the factors associated with overall survival of patients with HCC especially the elderly (≥ 75 years old). The results are interesting and give an useful information to the hepatologists in the world.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Jagannath Palepu, MS, FACS, FICS, FIMSA, FAMS, Chairman, Department of Surgical Oncology, Lilavati Hospital and Research Centre, Bandra Reclamation, Bandra (W), Mumbai 400050, India

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2651] [Cited by in RCA: 2598] [Article Influence: 108.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S35-S50. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Yuen MF, Hou JL, Chutaputti A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:346-353. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Dohmen K, Shigematsu H, Irie K, Ishibashi H. Trends in clinical characteristics, treatment and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1872-1877. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ikai I, Arii S, Okazaki M, Okita K, Omata M, Kojiro M, Takayasu K, Nakanuma Y, Makuuchi M, Matsuyama Y. Report of the 17th Nationwide Follow-up Survey of Primary Liver Cancer in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:676-691. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Umemura T, Kiyosawa K. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2007;37 Suppl 2:S95-S100. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Taura N, Yatsuhashi H, Nakao K, Ichikawa T, Ishibashi H. Long-term trends of the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the Nagasaki prefecture, Japan. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:223-227. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Michitaka K, Nishiguchi S, Aoyagi Y, Hiasa Y, Tokumoto Y, Onji M. Etiology of liver cirrhosis in Japan: a nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:86-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pignata S, Gallo C, Daniele B, Elba S, Giorgio A, Capuano G, Adinolfi LE, De Sio I, Izzo F, Farinati F. Characteristics at presentation and outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the elderly. A study of the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP). Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;59:243-249. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kondo K, Chijiiwa K, Funagayama M, Kai M, Otani K, Ohuchida J. Hepatic resection is justified for elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2008;32:2223-2229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Oishi K, Itamoto T, Kobayashi T, Oshita A, Amano H, Ohdan H, Tashiro H, Asahara T. Hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients aged 75 years or more. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:695-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang J, Li BK, Chen GH, Li JQ, Zhang YQ, Li GH, Yuan YF. Long-term outcomes and prognostic factors of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1627-1635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yau T, Yao TJ, Chan P, Epstein RJ, Ng KK, Chok SH, Cheung TT, Fan ST, Poon RT. The outcomes of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer. 2009;115:5507-5515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hiraoka A, Michitaka K, Horiike N, Hidaka S, Uehara T, Ichikawa S, Hasebe A, Miyamoto Y, Ninomiya T, Sogabe I. Radiofrequency ablation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:403-407. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Takahashi H, Mizuta T, Kawazoe S, Eguchi Y, Kawaguchi Y, Otuka T, Oeda S, Ario K, Iwane S, Akiyama T. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency ablation for elderly hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:997-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mirici-Cappa F, Gramenzi A, Santi V, Zambruni A, Di Micoli A, Frigerio M, Maraldi F, Di Nolfo MA, Del Poggio P, Benvegnù L. Treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients are as effective as in younger patients: a 20-year multicentre experience. Gut. 2010;59:387-396. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Ikai I, Takayasu K, Omata M, Okita K, Nakanuma Y, Matsuyama Y, Makuuchi M, Kojiro M, Ichida T, Arii S. A modified Japan Integrated Stage score for prognostic assessment in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:884-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fujii H, Tatumi N, Yoh T, Morita A, Kaneko , Ohkawara T, Minami Y, Ueda K, Sawa Y, Okanoue T. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of prognostic factors in patients receiving low-dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil. J Kyoto Prefectural University Med. 2006;115:887-898. |

| 19. | Hoshida Y, Ikeda K, Kobayashi M, Suzuki Y, Tsubota A, Saitoh S, Arase Y, Kobayashi M, Murashima N, Chayama K. Chronic liver disease in the extremely elderly of 80 years or more: clinical characteristics, prognosis and patient survival analysis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:860-866. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Tsukioka G, Kakizaki S, Sohara N, Sato K, Takagi H, Arai H, Abe T, Toyoda M, Katakai K, Kojima A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in extremely elderly patients: an analysis of clinical characteristics, prognosis and patient survival. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:48-53. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kozyreva ON, Chi D, Clark JW, Wang H, Theall KP, Ryan DP, Zhu AX. A multicenter retrospective study on clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and outcome in elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist. 2011;16:310-318. [PubMed] |

| 22. | El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557-2576. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Rocca LG, Yawn BP, Wollan P, Kim WR. Management of patients with hepatitis C in a community population: diagnosis, discussions, and decisions to treat. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:116-124. [PubMed] |

| 24. | McMahon BJ, Alward WL, Hall DB, Heyward WL, Bender TR, Francis DP, Maynard JE. Acute hepatitis B virus infection: relation of age to the clinical expression of disease and subsequent development of the carrier state. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:599-603. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Ascha MS, Hanouneh IA, Lopez R, Tamimi TA, Feldstein AF, Zein NN. The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1972-1978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 893] [Cited by in RCA: 963] [Article Influence: 64.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |