Published online Apr 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i15.1773

Revised: October 23, 2011

Accepted: January 18, 2012

Published online: April 21, 2012

AIM: To test the efficacy and safety of Profermin® in inducing remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis (UC).

METHODS: The study included 39 patients with mild to moderate UC defined as a Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) > 4 and < 12 (median: 7.5), who were treated open-label with Profermin® twice daily for 24 wk. Daily SCCAI was reported observer blinded via the Internet.

RESULTS: In an intention to treat (ITT) analysis, the mean reduction in SCCAI score was 56.5%. Of the 39 patients, 24 (62%) reached the primary endpoint, which was proportion of patients with ≥ 50% reduction in SCCAI. Our secondary endpoint, the proportion of patients in remission defined as SCCAI ≤ 2.5, was in ITT analysis reached in 18 of the 39 patients (46%). In a repeated-measure regression analysis, the estimated mean reduction in score was 5.0 points (95% CI: 4.1-5.9, P < 0.001) and the estimated mean time taken to obtain half the reduction in score was 28 d (95% CI: 26-30). There were no serious adverse events (AEs) or withdrawals due to AEs. Profermin® was generally well tolerated.

CONCLUSION: Profermin® is safe and may be effective in inducing remission of active UC.

- Citation: Krag A, Israelsen H, Ryberg BV, Andersen KK, Bendtsen F. Safety and efficacy of Profermin® to induce remission in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(15): 1773-1780

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i15/1773.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i15.1773

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic relapsing bowel disease characterized by colonic mucosal inflammation. The goal of treatment in UC is to induce and maintain remission of the disease. Failure to induce remission occurs in 20%-30% of patients on current treatments, leaving colectomy as the only alternative in a proportion of patients[1,2]. Furthermore, many patients find the side effects of treatment with corticosteroids and other drug therapies unacceptable. Accordingly, new treatment alternatives are being sought. The pathogenesis of UC has still not been determined in detail; however, a major hypothesis is suggested to be an aggressive immune response to the intestinal content including, a subset of nonpathogenic enteric bacteria in genetically predisposed individuals. Clinical and experimental studies point towards alterations in the relative balance of aggressive and protective bacterial species in these disorders[3,4]. Interventions to alter the intestinal microflora in order to decrease proinflammatory stimuli and increase anti-inflammatory signaling are under investigation[3,5,6]. Some studies have suggested an effect of probiotics in the treatment of UC[5,7-9]. The effects of probiotics on the microflora may only be limited and transient because colonization and survival of the probiotics are difficult to achieve. However, remission from inflammatory bowel diseases may be induced by food for special medical purposes (FSMPs), e.g., elemental diets. In this study we investigated a new dietary product Profermin®, which is intended to be registered as a FSMP for the dietetic management of UC. It consists of fermented oats, Lactobacillus plantarum (L. plantarum) 299v, barley malt, lecithin and water. Our aim was to investigate the safety and possible efficacy of Profermin® in patients with mild to moderate UC. We also assessed the usefulness of a new online daily symptom registration system.

The study was conducted between 2008 and 2009. Patients were eligible if they were between 18 and 50 years of age and had an established diagnosis of UC based on clinical, endoscopic and histological features. Active disease was assessed by Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) (Table 1) score > 4 and < 12[10]. Patients who initiated treatment with azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporin or methotrexate within 8 wk prior to inclusion or tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors within 12 wk before inclusion or had changes in UC treatment within 2 wk before inclusion were ineligible for the study. Concomitant celiac disease, lactose intolerance and irritable bowel syndrome were also exclusion criteria. In addition any malignant or premalignant condition or recent gastroenteritis and irritable bowel syndrome rendered patients ineligible. Patients were recruited through advertisement on the website of the local patients’ association, in local newspapers and through Google ads. The advertisement showed a link to a website that briefly described the trial and encouraged patients who were interested and had the relevant disease characteristics to contact the trial nurse. The patients had to sign a declaration stating when and where they had been diagnosed with UC and describing the course of their disease including the fulfillment of the inclusion criteria. The data were confirmed by cross checking the patients’ medical records. A specialist had diagnosed all patients.

| Symptom | Score |

| Bowel frequency (d) | |

| 1-3 | 0 |

| 4-6 | 1 |

| 7-9 | 2 |

| > 9 | 3 |

| Bowel frequency (night) | |

| 1-3 | 1 |

| 4-6 | 2 |

| Urgency of defecation | |

| Hurry | 1 |

| Immediately | 2 |

| Incontinence | 3 |

| Blood in stool | |

| Trace | 1 |

| Occasionally frank | 2 |

| Usually frank | 3 |

| General wellbeing | |

| Very well | 0 |

| Slightly below par | 1 |

| Poor | 2 |

| Very poor | 3 |

| Terrible | 4 |

| Extracolonic features | 1 per manifestation |

Patients were excluded if UC medication was modified during the study period, however, a dose reduction of ongoing drugs was accepted. The patients were also excluded if new medication that may affect UC symptoms was prescribed for other conditions.

Our primary endpoint was to estimate the proportion of patients with a ≥ 50% reduction in SCCAI. Our secondary endpoint was to estimate the proportion of patients in remission defined as SCCAI ≤ 2.5[11].

A prospective open-label study design was used to gain experience with time to response and remission and compliance for the later design of a comprehensive controlled study. After a run-in period of 6-14 d, the patients were followed for 24 wk with daily SCCAI score assessment. The SCCAI was chosen for the following reasons. The SCCAI score has been shown to correlate well with the more complex and invasive scoring systems and it facilitates daily and observer blinded symptoms registration[10,11]. Furthermore, colonoscopy may be experienced as painful and therefore compromise the patients’ willingness to participate in a clinical trial. Internet software was developed by a company specialized in software development for interactive Internet solutions (Franklyweb, Copenhagen, Denmark). The Internet platform was created according to protocol instructions and used for individual patient registration of SCCAI parameters. Regular access to a computer with Internet access was a criterion for inclusion. Each patient received a username and a password and was instructed to register the SCCAI parameters daily on the trial website. Each SCCAI parameter was formulated as a question e.g. “How many defecations have you experienced during daytime today? Click on the appropriate answer “1-3”, “4-6”, “7-9” or ”> 9”. Each SCCAI question needed to be answered before the patient could continue to the next question. After registration of the last SCCAI question, the patient was shown an overview of the answers to every SCCAI question and was asked to confirm or amend the information. After confirmation, the patient was shown a graph with the daily SCCAI scores from the first day of the run-in period up to the present date. The patients could communicate on the trial website with the nurse who checked the status of each patient at least twice a week and could send reminders if patients failed to register the daily symptoms. The symptoms were registered on a daily basis. When a patient failed to register a day’s symptoms, the patient was reminded by the nurse about the lacking registration. The registration rate (registered days out of total number of days) was > 95%. The data were transferred from the patients via the Internet in encrypted form (Secure Sockets Layer) and stored on a secure server. The data were instantly copied - in raw and unprocessed form - to a similar server at the Technical University of Denmark, Department of Informatics and Mathematical Modelling, in order to secure the authenticity of the data and to analyze the data statistically.

Occasionally some patients did not have access to a computer with an Internet connection. In such cases, these patients received paper SCCAI questionnaires to be completed for each day of the relevant period. When access to the Internet was again established, the patients transferred the SCCAI parameters noted on the questionnaires to the website. During the screening process, 30 of the included patients (77%) had a face-to-face meeting with the trial nurse. There were no other face-to-face contacts with the patients. All other communication was electronic (phone or e-mail). The patients were instructed to report adverse events (AEs) via the trial website. Safety of Profermin® was assessed by analyzing the AE reports.

Profermin® is manufactured as follows. Oat gruel is produced by mixing oats, water and a small amount of barley malt. The mixing process lasts for 1 h at 88 °C. The gruel is then cooled to 38 °C, and a L. plantarum 299v starter culture is added. The mixture is kept at 38 °C for 15 h with constant gentle stirring. The resulting oat-fermented gruel is cooled to about 8 °C. Lecithin is then added while the mixture is gently stirred and the resulting Profermin® is packed in 250-mL cartons under sterile conditions. The product is tested for pH and colony forming units (CFU) of Enterobacteriaceae, yeasts/moulds and L. plantarum 299v. The pH must be between 3.6 and 4.2 and the CFU of Enterobacteriaceae, yeasts/moulds must each be < 100/mL. The CFU of L. plantarum must be > 108/mL.

After 6-14 d of run in, the Profermin® intervention was initiated by scaling the patient into a daily oral intake of Profermin®. The initial daily Profermin® dose was 125 mL as the first meal and 125 mL as the last meal of the day. After 2 d, the Profermin® dose was increased to 250 mL as the first meal and 250 mL as the last meal of the day. However, the protocol was open for periodical changes of the total dose of Profermin® in the interval of 25 mL to 500 mL taken once or twice daily, for example, if a patient experienced AEs during the introduction, the low Profermin® dose was prolonged for up to 2 wk. The median dose was 445 mL/d with an interquartile range of 408-500 mL/d. The patients reported their intake of Profermin® on a daily basis through the trial website and the mean self-reported adherence therapy was > 95%.

Patients were recommended to be cautious with consumption of dairy products and concentrated sugar products in accordance with routine dietetic recommendations widely used in Danish IBD clinics[6]. Compliance with this recommendation was not monitored. Patients continued their usual UC medication and clinical follow-up with gastroenterologists.

The trial was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2008-41-2961) and has been cleared with The Ethical Committees of the Copenhagen Region and registered (H-B-2008-FSP-20). As Profermin® is an FSMP and not a medicinal product, no authorization by the Danish Medicines Agency was required. All patients gave written informed consent according to the Helsinki declaration. The study was registered on http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01245465).

In all analyses, we applied the principle of intention-to-treat (ITT). Data for patients who dropped out or who were excluded during the study period were included in the analysis by using the principle of last value carried forward. Unadjusted estimates for the primary and secondary endpoints were presented as total numbers and percentages. To gain further insight into the longitudinal effect of Profermin® on the possible decline in SCCAI over time adjusted for the starting value, we applied the following non-linear regression model:

Scoreij = β0 + β1× 2-Dayi/θ

Where the dependent variable Scoreij was the score for person j on Day i. Time was denoted by the independent variable Dayi. In the model, the parameters to be estimated had the following interpretation: β0 was the ultimate score (or asymptote), β1 was the total reduction in score and θ was the time taken to obtain half the reduction in score. Besides giving the parameters a marginal interpretation, it was of interest to describe the between-patient variation. Thus, we applied a nonlinear mixed-effects model, assuming that all three parameters in question followed a Gaussian distribution, i.e., each parameter was person-specific:

Scoreij = β0,j + β1,j× 2-Dayi/θj

Here, we assumed that β0,j = N(β0,σβ0), β1,j = N(β1,σβ1) and θj = N(θ,σθ). The mixed-effect model led to the following interpretation: the estimated parameter σβ0 was the between-person SD regarding the asymptote. Similarly, σβ1 was the between-person SD related to the total reduction in score, and σθ was the between-person SD related to the time taken to obtain half the reduction in score.

Before making inference, we examined both standardized residuals and estimated random effects for marginal normality by applying normal probability plots. In all statistical analysis, the software R and the package nlme were used. All tests were done as likelihood ratio tests with a significance level of 5%.

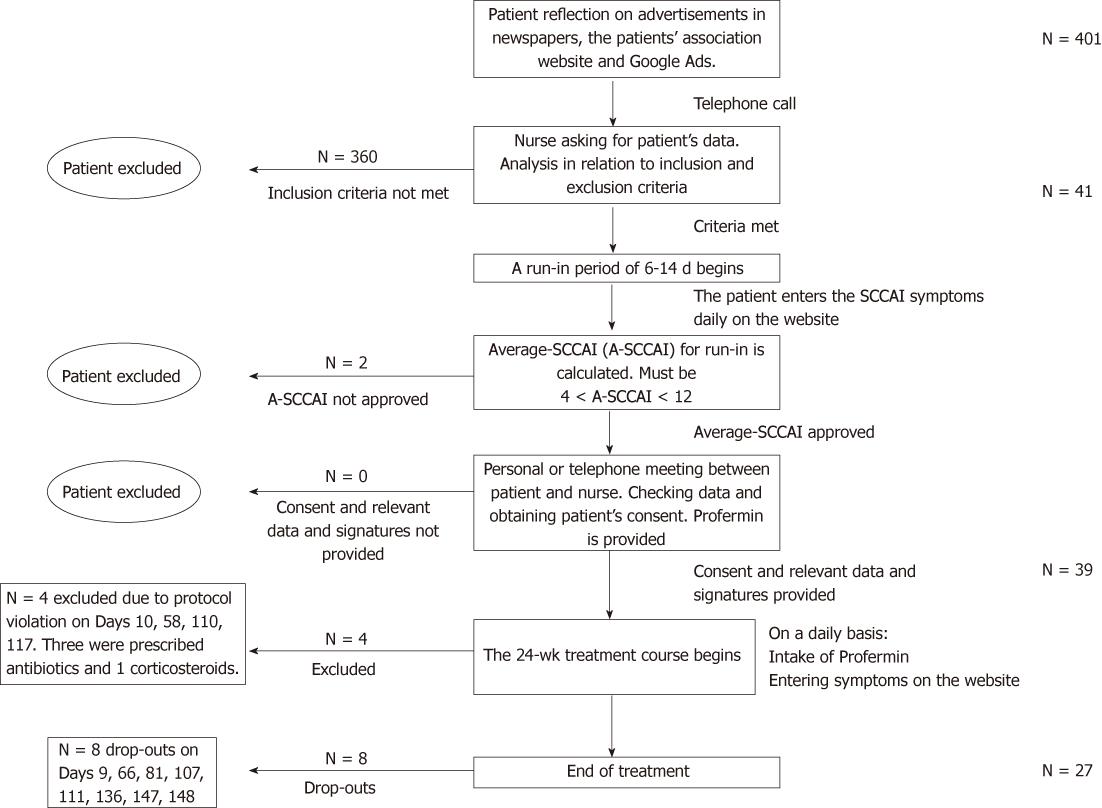

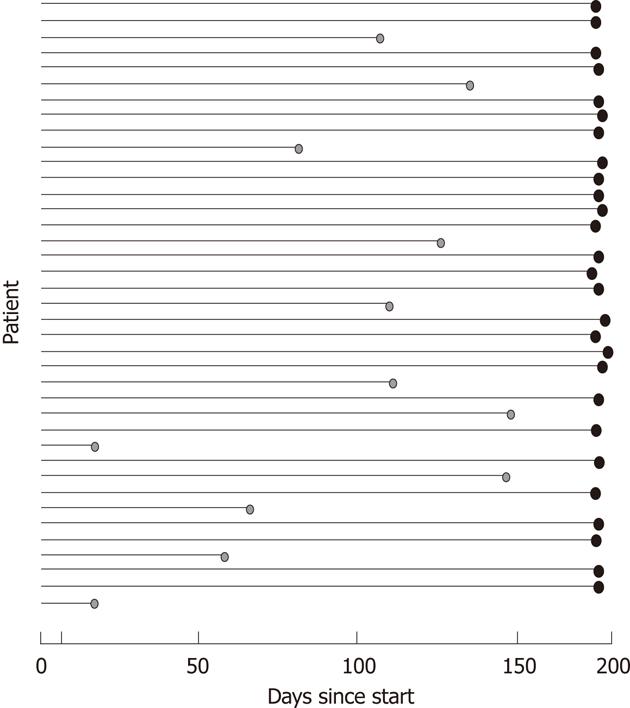

The advertisements attracted 401 respondents, of whom 360 were excluded before the run-in period because the inclusion criteria were not met (Figure 1). Reasons for exclusions were primarily SCCAI < 5 or recent change in oral corticosteroid treatment. During the run-in period, two additional patients were excluded because the SCCAI criteria were not met. The study comprised 39 patients who were available for ITT analysis: four were excluded and eight dropped out during the 24-wk treatment period (Figure 2 and Table 2).

| Day | SCCAI run in | Reason for discontinuation | SCCAI dropout | Reduction | Increase |

| Excluded patients | |||||

| 10 | 8.9 | 1 | 6.6 | 2.3 | |

| 45 | 8.0 | 1 | 4.1 | 3.9 | |

| 100 | 8.2 | 1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | |

| 116 | 11 | 2 | 3.6 | 7.4 | |

| Drop-outs | |||||

| 9 | 8.9 | 3 | 6.7 | 2.2 | |

| 54 | 4.6 | 3 | 5.1 | 0.5 | |

| 73 | 5.9 | 3 | 7.3 | 1.4 | |

| 100 | 5.6 | 3 | 8.4 | 2.8 | |

| 102 | 9.0 | 3 | 6.7 | 2.3 | |

| 127 | 6.6 | 3 | 5.6 | 1.0 | |

| 140 | 6.7 | 3 | 5.3 | 1.4 | |

| 141 | 8.3 | 3 | 6.3 | 2.0 | |

Baseline characteristics and use of concomitant medications are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

| Characteristic | Profermin, n = 39 |

| Sex, male:female | 15/24 |

| Age, yr, median and range | 35 (19-50) |

| Mean duration of disease, yr, median and range | 7 (1-21) |

| Disease location, n (%) | |

| Proctitis | 17 (44) |

| Left-sided colitis/procto-sigmoiditis | 11 (28) |

| Pancolitis | 11 (28) |

| Extraintestinal manifestations, n (%) | 17 (43) |

| Initial CRP, mg/L, median and range | 15 (< 1-156) |

| Initial albumin, g/L, median and range | 41 (23-47) |

| n (%) | |

| Mesalamine oral | |

| Alone | 21 (54) |

| Combined with immunosuppressants | 8 (21) |

| Mesalamine enema or suppository | 6 (15) |

| Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine | 3 (8) |

| Corticosteroids oral | 0 (0) |

| Corticosteroids enema | 1 (3) |

| Antibiotics | 0 (0) |

| TNF-α inhibitors | 3 (8) |

| None | 3 (8) |

No major AEs were reported and there were no dropouts due to AEs. An increased number of bowel movements were reported by 11 patients (28%), bloating by four (10%) and an increased number of bowel movements and bloating by three (8%). All AEs were self-limiting or managed by dose adjustments. For example, if a patient experienced a presumable AE during the introduction of Profermin®, the period with the low Profermin® dose was prolonged for up to 2 wk. None of the eight dropout or four excluded patients left the trial due to deterioration in UC symptoms.

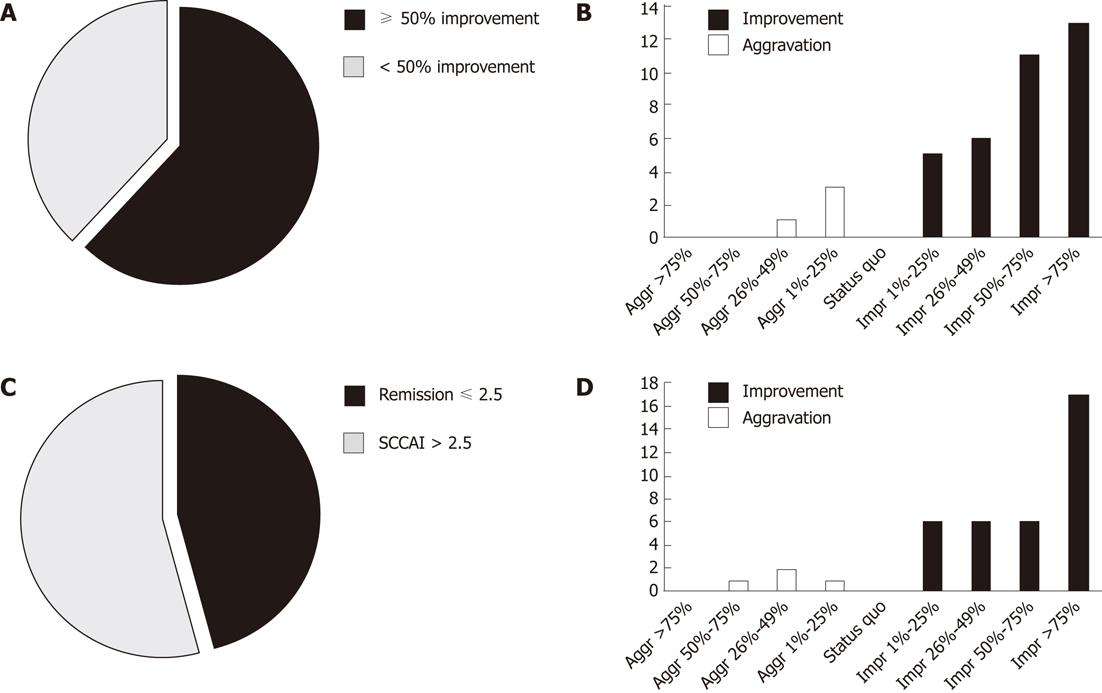

Of the 39 patients, 27 completed the entire study. For those completing the study, the mean follow-up was 176 d (range: 174-179 d). For those not completing the study, the mean follow-up was 94 d (range: 9-141 d). An ITT analysis showed that the mean reduction in SCCAI score was 56.5%. For the primary endpoint, ITT analysis showed that 24 of the 39 patients (62%) achieved a ≥ 50% reduction in SCCAI score (Figure 3A). In per protocol (PP) analysis, 85% reached the primary endpoint. In ITT analysis, four patients (10%) experienced deterioration in SCCAI but 13 (33%) experienced > 75% improvement in SCCAI during the study (Figure 3B). Of the 39 patients, 18 reached the secondary endpoint and obtained remission defined as SCCAI score ≤ 2.5, with an ITT success rate of 46% (Figure 3C). In PP analysis, 67% reached the secondary endpoint remission. Applying only the four defecation scores in the SCCAI (Table 1), four patients (10%) had deterioration and 17 (44%) had > 75% improvement in defecations scores (Figure 3D).

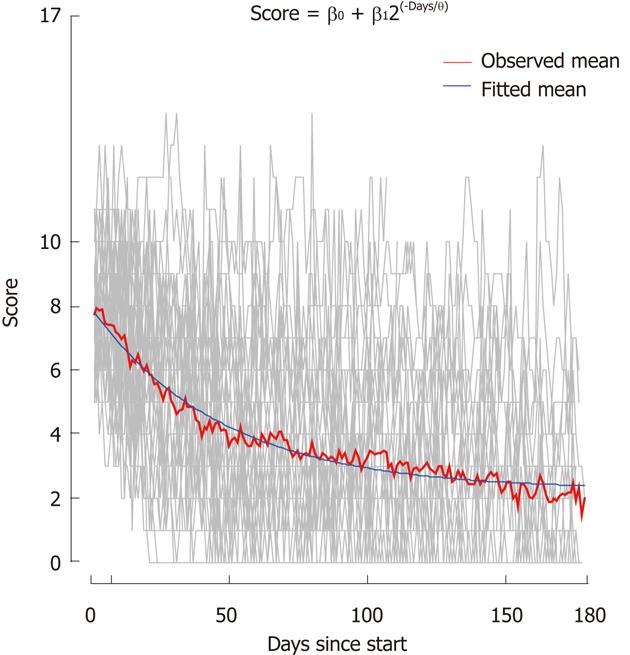

When applying the nonlinear model for the ITT decline in SCCAI over time, the estimated ultimate score (or asymptote) was 2.8 points (95% CI: 92.0-3.6), the estimated mean reduction in score was 5.0 points (95% CI: 4.1-5.9, P < 0.0001) and the estimated mean time taken to obtain half of the reduction in score was 28 d (95% CI: 26-30) (Figure 4).

Protocol violations accounted for the exclusion of four patients (10%) - days 10, 45, 100 and 116 (Table 4); three were prescribed antibiotics for pneumonia, salmonella infection and gastroenteritis, respectively, and one was prescribed corticosteroids for UC. Among those excluded, the mean SCCAI on inclusion was 9.0 (range: 8.0-11) and at exclusion 4.6 (range: 3.6-6.6). There were eight dropouts (20%) (Table 2). Among these, the mean SCCAI at inclusion was 7.0 (range: 4.6-9.0) and at dropout 6.4 (range: 5.1-8.4). Among the dropouts, three experienced an increase in SCCAI (mean: 1.6) while in the study and five experienced a decrease (mean: 1.8). The three patients with an increase in their SCCAI score represented treatment failures.

In ITT analysis, 62% of the patients reached the primary endpoint, defined as ≥ 50% reduction in SCCAI, and 46% reached the secondary endpoint of remission, defined as an SCCAI score ≤ 2.5. A study on endpoints for clinical improvement and remission in UC found a relevant clinical improvement to be a decrease of 1.5 SCCAI points and the best cut-off to establish remission as an SCCAI of 2.5[11]. In ITT analysis, the average reduction was > 1.5 SCCAI points 12 d after the intervention was initiated. After 32 d, the average reduction increased to > 3 SCCAI points and after 84 d to > 4.5 (Figure 4). In a repeated measure regression analysis, the mean reduction in SCCAI after 24 wk of Profermin® treatment, adjusted for baseline value, was 5.0 and the estimated ultimate score was calculated to be 2.8 (Figure 4), suggesting a clinically relevant and significant effect. A meta-analysis of response rates in the placebo arms of UC trials estimated the placebo rates of remission and response to be 13% (95% CI: 9-18) and 28% (95% CI: 23-33), respectively[12]. The ITT remission and response rates in our study were 33 and 34 percentage points above these standard placebo rates, supporting a possible clinical effect of Profermin® when compared with standard placebo rates of response and remission. The safety profile of Profermin® appears favorable with no major AEs and no withdrawals due to AEs. Mild AEs were observed mainly in the initial days of treatment and ceased within a few days or after dose adjustments. Safety and tolerability of Profermin® are comparable to those of probiotics[7-9].

Profermin® is a complex product and the mode of action is probably complex as well. However, dietary management with Profermin® uses a novel approach and cannot be categorized as a probiotic, prebiotic or symbiotic product[13]. The dietary effect may be related to the fermented oats components such as the relatively large amounts of secondary metabolites from the fermentation process and the composition of oats per se. The short chain fatty acids of secondary metabolites have been shown to serve as a major source of energy for colonocytes, and β-glucans have been described as biological response modifiers[14,15]. L. plantarum is a common species in the human gastrointestinal microbiota[16-18]. L. plantarum 299v survives passage through the gastrointestinal tract and has been isolated from feces and rectal and jejunal biopsies 11 d after 10 d administration to healthy volunteers, indicating at least transient colonization of the gut mucosa[19-21]. It has been shown that oat gruel fermented with L. plantarum 299v increases iron absorption by 50%, suggesting an important dietary effect for UC[22]. In addition, the phosphatidylcholine (PC) in lecithin may serve as an important food component because the content of PC in the colonic mucus of patients with UC is significantly lower compared with the content in healthy controls[23]. Lastly, the daily intake of relatively large quantities of fermented oats may change the intestinal contents and environment and thereby establish an altered platform for microbial activity.

In this study, we introduced a new online self-reporting Internet-based system for assessing daily activity in UC and for monitoring response to treatment. The system allows electronic monitoring of data and enables daily reporting with minimal interruption to the patient’s daily life. The risk of patients being influenced in their self-assessment by health personnel is limited. Independent monitoring and statistical analyses can be achieved easily. In Denmark, where most people have Internet access, this system is a very useful research tool in a population of UC patients.

Our study had some limitations: (1) it was an uncontrolled study and the results need to be confirmed in a randomized trial; and (2) patients were informed to consider their consumption of dairy products and concentrated sugar products, in particular fresh milk and confectionary. This may have had an effect on UC or may have reinforced the effect of Profermin®.

The present study demonstrates that Profermin® is safe and may be effective in inducing remission of active UC. Randomized controlled studies are planned to explore further the clinical efficacy of Profermin®.

We thank Jørgen Villumsen for invaluable practical and technical assistance. We also thank Peter Møller and Carsten Toftager Larsen for important advice during the study.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic relapsing bowel disease. The goal of treatment in UC is to induce and maintain remission of the disease, however, failure to induce remission occurs in 20%-30% of patients on current treatments. Accordingly, new treatment alternatives and additives are being sought. Dietetic interventions may improve symptoms in UC.

Clinical and experimental studies point towards alterations in the relative balance of aggressive and protective bacterial species in UC. Interventions to alter the intestinal microflora in order to decrease disease activity are under investigation and prebiotics, probiotics and symbiotics have been investigated in UC but the reported efficacies have varied.

This is believed to be the first study to assess Profermin® in UC. The study was an open label study that investigated safety and efficacy of Profermin® in patients with moderate active UC. Profermin® is a new developed product for the dietary management of UC. It is a fermented oat gruel with Lactobacillus plantarum 299v, barley malt, lecithin and water.

Profermin® is safe and well tolerated and may be effective in reducing symptoms and inducing remission in UC. Larger randomized trials should be performed to investigate further the efficacy of Profermin® in UC.

Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) assessed active disease. SCCAI is a clinical scoring system for UC, based on bowel frequency day and night, urgency, fecal blood, general well being and extracolonic manifestations.

The authors have reported a study on the safety of Profermin®, a combination of fermented oats, probiotics and lecithin, in patients with mild to moderate UC. This is primarily an open-label safety study in patients. The agent was well-tolerated and may be efficacious.

Peer reviewer: Alan C Moss, MD, FACG, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of Translational Research, Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Rose 1 / East, 330 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215, United States

S- Editor Shi ZF L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Aratari A, Papi C, Clemente V, Moretti A, Luchetti R, Koch M, Capurso L, Caprilli R. Colectomy rate in acute severe ulcerative colitis in the infliximab era. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:821-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369:1641-1657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1247] [Cited by in RCA: 1353] [Article Influence: 75.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sartor RB. Therapeutic manipulation of the enteric microflora in inflammatory bowel diseases: antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1620-1633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 726] [Cited by in RCA: 718] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Baumgart DC, Carding SR. Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology. Lancet. 2007;369:1627-1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1299] [Cited by in RCA: 1506] [Article Influence: 83.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Prisciandaro L, Geier M, Butler R, Cummins A, Howarth G. Probiotics and their derivatives as treatments for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1906-1914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yamamoto T, Nakahigashi M, Saniabadi AR. Review article: diet and inflammatory bowel disease--epidemiology and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:99-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bibiloni R, Fedorak RN, Tannock GW, Madsen KL, Gionchetti P, Campieri M, De Simone C, Sartor RB. VSL#3 probiotic-mixture induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1539-1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 503] [Cited by in RCA: 491] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huynh HQ, deBruyn J, Guan L, Diaz H, Li M, Girgis S, Turner J, Fedorak R, Madsen K. Probiotic preparation VSL#3 induces remission in children with mild to moderate acute ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:760-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sood A, Midha V, Makharia GK, Ahuja V, Singal D, Goswami P, Tandon RK. The probiotic preparation, VSL#3 induces remission in patients with mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1202-1209, 1209.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, Allan RN. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 857] [Cited by in RCA: 1037] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Higgins PD, Schwartz M, Mapili J, Krokos I, Leung J, Zimmermann EM. Patient defined dichotomous end points for remission and clinical improvement in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2005;54:782-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Su C, Lewis JD, Goldberg B, Brensinger C, Lichtenstein GR. A meta-analysis of the placebo rates of remission and response in clinical trials of active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:516-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bengmark S, Martindale R. Prebiotics and synbiotics in clinical medicine. Nutr Clin Pract. 2005;20:244-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Roy CC, Kien CL, Bouthillier L, Levy E. Short-chain fatty acids: ready for prime time? Nutr Clin Pract. 2006;21:351-366. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Volman JJ, Ramakers JD, Plat J. Dietary modulation of immune function by beta-glucans. Physiol Behav. 2008;94:276-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Christensen HR, Frøkiaer H, Pestka JJ. Lactobacilli differentially modulate expression of cytokines and maturation surface markers in murine dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:171-178. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Ahrné S, Nobaek S, Jeppsson B, Adlerberth I, Wold AE, Molin G. The normal Lactobacillus flora of healthy human rectal and oral mucosa. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;85:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lönnermark E, Friman V, Lappas G, Sandberg T, Berggren A, Adlerberth I. Intake of Lactobacillus plantarum reduces certain gastrointestinal symptoms during treatment with antibiotics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:106-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Niedzielin K, Kordecki H, Birkenfeld B. A controlled, double-blind, randomized study on the efficacy of Lactobacillus plantarum 299V in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1143-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Johansson ML, Molin G, Jeppsson B, Nobaek S, Ahrné S, Bengmark S. Administration of different Lactobacillus strains in fermented oatmeal soup: in vivo colonization of human intestinal mucosa and effect on the indigenous flora. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:15-20. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Adlerberth I, Ahrne S, Johansson ML, Molin G, Hanson LA, Wold AE. A mannose-specific adherence mechanism in Lactobacillus plantarum conferring binding to the human colonic cell line HT-29. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2244-2251. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Bering S, Suchdev S, Sjøltov L, Berggren A, Tetens I, Bukhave K. A lactic acid-fermented oat gruel increases non-haem iron absorption from a phytate-rich meal in healthy women of childbearing age. Br J Nutr. 2006;96:80-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ehehalt R, Wagenblast J, Erben G, Lehmann WD, Hinz U, Merle U, Stremmel W. Phosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylcholine in intestinal mucus of ulcerative colitis patients. A quantitative approach by nanoElectrospray-tandem mass spectrometry. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:737-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |