Published online Mar 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i12.1410

Revised: July 28, 2011

Accepted: February 27, 2012

Published online: March 28, 2012

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a group of idiopathic disorders characterized by the proliferation of specialized, bone marrow-derived langerhans cells and mature eosinophils. The clinical spectrum ranges from an acute, fulminant, disseminated disease called Letterer-Siwe disease to solitary or few, indolent and chronic lesions of the bone or other organs called eosinophilic granuloma. Involvement of the gastrointestinal tract is very rare in LCH. We present the case of a 53-year-old woman referred by her primary care physician for a screening colonoscopy. A single sessile polyp, measuring 4 mm in size, was found in the rectum. Histopathological examination revealed that the lesion was relatively well circumscribed and comprised mainly a mixture of polygonal cells with moderate-to-abundant pink slightly granular cytoplasm. The nuclei within these cells had frequent grooves and were occasionally folded. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD-1a which confirmed the diagnosis of LCH. On further workup, there was no evidence of involvement of any other organ. On follow up colonoscopy one year later, there was no evidence of disease recurrence. Review of the published literature revealed that LCH presenting as solitary colonic polyp is rare. However, with the increasing rates of screening colonoscopy, more colonic polyps may be identified as LCH on histopathology. This underscores the importance of recognizing this rare condition and ensuring proper follow-up to rule out systemic disease.

- Citation: Shankar U, Prasad M, Chaurasia OP. A rare case of langerhans cell histiocytosis of the gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(12): 1410-1413

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i12/1410.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i12.1410

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a group of idiopathic disorders characterized by the proliferation of specialized, bone marrow-derived langerhans cells (LCs) and mature eosinophils. The clinical spectrum of LCH ranges from an acute, fulminant, disseminated disease (called Letterer-Siwe disease) to solitary or few indolent and chronic lesions of the bone or other organs called (eosinophilic granuloma). The intermediate clinical form, called Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, is characterized by multifocal, chronic involvement and classically presents as a triad of diabetes insipidus, proptosis and lytic bone lesions.

LCH is a rare disease of the pediatric population, with an estimated annual incidence of 4-5 per million. More than two-thirds of cases have single system disease with bones and skin as the most commonly involved sites[1,2]. Other organs involved are the lung, liver, spleen, bone marrow, lymph nodes and the hypothalamic-pituitary region[3]. Involvement of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is very rare in LCH, especially in adults, with only a few isolated case reports available in English-language literature[4].

The pathogenesis of LCH is unknown. An ongoing debate exists over whether this is a reactive or neoplastic process. From the histopathological viewpoint, the demonstration of LC (Birbeck) granules by electron microscopy remains the ‘‘gold standard’’ for diagnosis of the phenotype, but expression of the CD1a antigen on lesional cells also provides the basis for a definitive diagnosis[5].

We present a case of a 53-year-old woman with a history of hyperlipidemia who was referred by her primary care physician for a screening colonoscopy. She was essentially asymptomatic and did not report any abdominal pain, blood in stool, change in bowel habits, dysphagia, nausea, or vomiting. Findings of physical examination were unremarkable.

On colonoscopy, quality of bowel preparation was excellent. A single sessile polyp measuring 4 mm in size was found in the rectum (Figure 1). It was removed by cold snare polypectomy. The procedure was performed without complications.

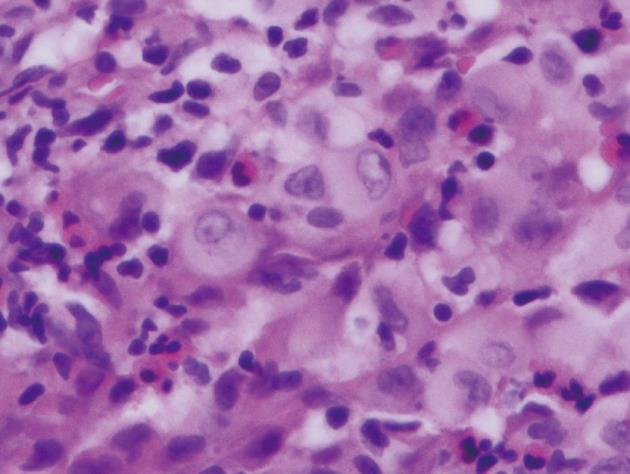

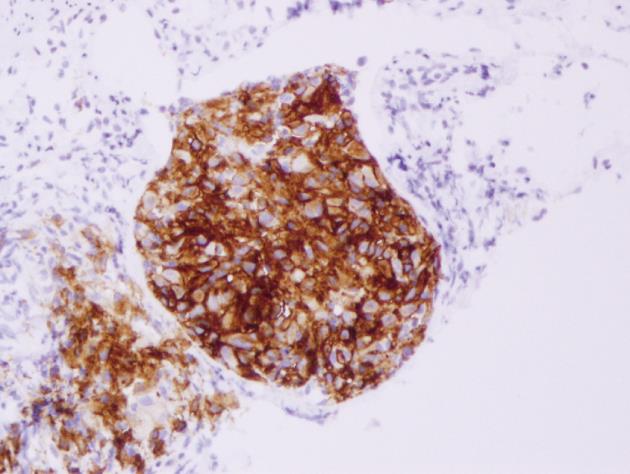

Histopathological examination of the polyp revealed that the lesion was relatively well-circumscribed and comprised mainly a mixture of polygonal cells. These cells had moderate-to-abundant pink slightly granular cytoplasm. The lesion also contained inflammatory cells. The inflammatory populations included eosinophils, lymphocytes and neutrophils. The nuclei within the larger cells had frequent grooves and were occasionally folded, suggesting the presence of LCs (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining showed histiocytes with cytoplasmic and membranous staining for CD-1a (Figure 3). Histiocyte cytoplasm was positive for S-100 and negative for prekeratin on immunohistochemistry. Electron microscopy was not performed to document presence of Birbeck granules as staining for CD-1a was strongly positive and provided confirmation for the diagnosis[5].

The patient was referred for medical oncology evaluation for this unusual pathologic finding with malignant potential. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed to rule out any metastasis through staging evaluation. The CT scan showed no evidence of metastasis, although there were fibroids in the uterus and few cystic masses in the ovaries. Some prominent lymph nodes, which appeared to be benign, were observed in the right and left axillae and sub carina. Further evaluation by an oncologist and a gynecologist revealed that these lesions were benign. Therefore, we found no evidence of disseminated LCH.

The patient remained asymptomatic, and a follow-up colonoscopy was performed 1 year later. A single sessile polyp, measuring 4 mm, was found in the rectum. Another single sessile polyp, measuring 5 mm, was found in the proximal ascending colon. Histopathological examination showed that the polyps were hyperplastic and tubular adenomatous polyps, respectively.

In the GI tract, LCH involvement of the stomach[6-8], small intestine[9-11], colon[4,12,13] and perianal skin[14,15] has been reported. Rectal LCH, proven by histopathology, has been described in infants presenting with bloody diarrhea. In most cases, rectal LCH in infants is indicative of widespread, multisystem disease[16].

Among the 6 reported cases of LCH of stomach, all patients were in the fourth and fifth decade of life, and the male-to-female ratio was 1:1; five patients presented with abdominal pain, and one was asymptomatic. The gastric lesion was described as a large, flat raised area in 1 case and a single polyp in 1 case. In other 2 cases, the gastric lesion was described as an ulcerating mass and multiple polyposis, respectively. Histopathological examination of lesions from 2 cases revealed malignant features[8,17]. In the case reported by Terracciano et al[8], the patient presented with abdominal pain and weight loss; the tumor was located on the lesser curvature of the stomach. During laparotomy, the tumor was found to have invaded the distal pancreas. Some areas of the tumor had high mitotic indexes and cytologic atypia. Most neoplastic cells were intensely positive for vimentin, S-100 and CD 1a on immunohistochemistry. Two months after surgical resection, the patient died at home. The cause of death was unclear. The remainder of the cases did not show histopathological or clinical malignant features.

Small bowel LCH is rare, with only 3 cases being reported in infants[10,18] and 1 in an adult[11]. All infants with small bowel LCH presented with diarrhea, weight loss, and failure to thrive. Laboratory findings were significant for anemia and hypoalbuminemia, and the duodenum was always involved. All patients simultaneously or subsequently developed widespread, multisystem involvement, requiring chemotherapy. Two patients responded well to chemotherapy with complete remission, but 1 succumbed to the disease after poor response to treatment and finally refusing chemotherapy[18]. In adults, only 1 proven case of small bowel LCH has been reported. LCH occurred in a patient who had undergone right hemicolectomy for steroid-refractory Crohn’s disease; this patient presented with worsening diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Barium follow-through showed extensive mucosal infiltration of the small bowel wall, and the duodenal biopsy result was consistent with a diagnosis of LCH. Results of bone marrow examination were consistent with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. The authors concluded that in this case, LCH was a complication of Crohn’s disease because of the increased incidence of myeloproliferative disorders in inflammatory bowel disease[11,19].

In children, colonic involvement in LCH is extremely rare. Only 1 case of LCH has been reported in an infant who died of widespread multisystem disease consistent with Litterer-Siwe disease; LCH was diagnosed post-mortem in this case[13]. In adults, there have been only 2 reported cases of colonic LCH presenting as isolated polyps in English-language literature[4,12]. Both patients were essentially asymptomatic, and polyps were detected during screening colonoscopy. In both cases, diagnosis was confirmed by positive immunochemical staining for CD1a antigen. Extensive workup in both cases did not reveal involvement of any other organ. In the case presented herein, a polyp was located in the rectum, and diagnosis was supported by the presence of an eosinophilic infiltrate and LCs. The diagnosis was confirmed by strong immunochemical staining for CD1a antigen. The workup to rule out involvement of other organs was negative, and repeat colon examination did not reveal recurrence.

In conclusion, LCH of the GI tract is extremely rare. Colonic involvement in adults usually presents as a solitary polyp without multisystem disease. With the increasing rates of screening colonoscopy, more colonic polyps may be identified as LCH on histopathology. This underscores the importance of recognizing this rare condition and ensuring proper follow-up to rule out systemic disease.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Edward J Ciaccio, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, City of New York, NY 10032, United States; Dr. Benito Velayos, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital Clínico Valladolid Ramón y Cajal 3, Valladolid 47003, Spain

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Salotti JA, Nanduri V, Pearce MS, Parker L, Lynn R, Windebank KP. Incidence and clinical features of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in the UK and Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:376-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, Bellec S, Thomas C, Clavel J. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000-2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Windebank K, Nanduri V. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:904-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sharma S, Gupta M. A colonic polyp due to Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a lesion not to be confused with metastatic malignant melanoma. Histopathology. 2006;49:438-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Favara BE, Feller AC, Pauli M, Jaffe ES, Weiss LM, Arico M, Bucsky P, Egeler RM, Elinder G, Gadner H. Contemporary classification of histiocytic disorders. The WHO Committee On Histiocytic/Reticulum Cell Proliferations. Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:157-166. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Iwafuchi M, Watanabe H, Shiratsuka M. Primary benign histiocytosis X of the stomach. A report of a case showing spontaneous remission after 5 1/2 years. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:489-496. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Wada R, Yagihashi S, Konta R, Ueda T, Izumiyama T. Gastric polyposis caused by multifocal histiocytosis X. Gut. 1992;33:994-996. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Terracciano L, Kocher T, Cathomas G, Bubendorf L, Lehmann FS. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the stomach with atypical morphological features. Pathol Int. 1999;49:553-556. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Sutphen JL, Fechner RE. Chronic gastroenteritis in a patient with histiocytosis-X. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5:324-328. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Patel BJ, Chippindale AJ, Gupta SC. Case report: small bowel histiocytosis-X. Clin Radiol. 1991;44:62-63. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lee-Elliott C, Alexander J, Gould A, Talbot R, Snook JA. Langerhan's cell histiocytosis complicating small bowel Crohn's disease. Gut. 1996;38:296-298. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Kibria R, Gibbs PM, Novick DM. Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a rare cause of colon polyp. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E160-E161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hyams JS, Haswell JE, Gerber MA, Berman MM. Colonic ulceration in histiocytosis X. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1985;4:286-290. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sabri M, Davie J, Orlando S, Di Lorenzo C, Ranganathan S. Gastrointestinal presentation of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a child with perianal skin tags: a case report. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:564-566. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Mittal T, Davis MD, Lundell RB. Perianal Langerhans cell histiocytosis relieved by surgical excision. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:213-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee RG, Braziel RM, Stenzel P. Gastrointestinal involvement in Langerhans cell histiocytosis (histiocytosis X): diagnosis by rectal biopsy. Mod Pathol. 1990;3:154-157. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Zeman V, Havlík J. [Histiocytosis X: isolated extraosseous eosinophil gastric reticuloma (author's transl)]. Cesk Gastroenterol Vyz. 1980;34:255-258. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Egeler RM, Schipper ME, Heymans HS. Gastrointestinal involvement in Langerhans' cell histiocytosis (Histiocytosis X): a clinical report of three cases. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;149:325-329. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Pedersen N, Duricova D, Elkjaer M, Gamborg M, Munkholm P, Jess T. Risk of extra-intestinal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1480-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |