Published online Mar 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i9.1160

Revised: June 21, 2010

Accepted: June 28, 2010

Published online: March 7, 2011

AIM: To test the Genval recommendations and the usefulness of a short trial of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) in the initial management and maintenance treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients.

METHODS: Five hundred and seventy seven patients with heartburn were recruited. After completing a psychometric tool to assess quality of life (PGWBI) and a previously validated GERD symptom questionnaire (QUID), patients were grouped into those with esophagitis (EE, n = 306) or without mucosal damage (NERD, n = 271) according to endoscopy results. The study started with a 2-wk period of high dose omeprazole (omeprazole test); patients responding to this PPI test entered an acute phase (3 mo) of treatment with any PPI at the standard dose. Finally, those patients with a favorable response to the standard PPI dose were maintained on a half PPI dose for a further 3-mo period.

RESULTS: The test was positive in 519 (89.9%) patients, with a greater response in EE patients (96.4%) compared with NERD patients (82.6%) (P = 0.011). Both the percentage of completely asymptomatic patients, at 3 and 6 mo, and the reduction in heartburn intensity were significantly higher in the EE compared with NERD patients (P < 0.01). Finally, the mean PGWBI score was significantly decreased before and increased after therapy in both subgroups when compared with the mean value in a reference Italian population.

CONCLUSION: Our study confirms the validity of the Genval guidelines in the management of GERD patients. In addition, we observed that the overall response to PPI therapy is lower in NERD compared to EE patients.

- Citation: Pace F, Riegler G, Leone A, Dominici P, Grossi E, Group TES. Gastroesophageal reflux disease management according to contemporary international guidelines: A translational study. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(9): 1160-1166

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i9/1160.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i9.1160

In 1999 an international panel of experts involved in the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) convened in Genval, Belgium, for a workshop which aimed to review the existing evidence concerning the definition, pathogenesis and natural history, and impact of the disease on the patient, and clinical manifestations as well as diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. The results of this workshop were published as the “The Genval Workshop Report”[1], and had a substantial impact both on the management strategies in GERD and in the development of further guidelines, as for example the Marrakech Workshop[2] and the Montreal Global Definition[3].

The Genval recommendations constitute a comprehensive body of knowledge relevant to good management. In 2002 we designed a multicenter study on GERD patients with the primary aim of testing “in the field” the Genval recommendations and to prospectively evaluate: (1) the usefulness of a short trial of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) in the initial management of GERD; and (2) the usefulness of a step-down PPI in the maintenance treatment of GERD patients.

As secondary aims we wanted to assess the ability of PPI maintenance therapy to restore the quality of life of our patients and to assess the ability in differentiating between erosive and non erosive disease by a new GERD questionnaire, the QUestionario Italiano Diagnostico (QUID), which has been created by application of artificial neural networks as reported elsewhere[4]. The latter issue will be described in a separate paper.

This study was a national multicenter collaborative investigation (the EMERGE project). The study was conducted on GERD patients with or without erosive esophagitis between June 2003 and June 2005. The study started with a 2-wk period of high dose omeprazole 20 mg bid (the so-called omeprazole test). Patients responding to this test entered an acute phase (3 mo) of treatment with any available PPI at a standard dose. Finally, those patients with a favorable response to the standard PPI dose were maintained on half the PPI dose for a further 3-mo period. Patients continued this regimen unless their symptoms relapsed: in this case, they could resume the previous dose. Patients requiring this change of therapy more than once were considered to have treatment failure and were excluded from the final analysis.

The study was conducted according to good clinical practices. All Ethics Committees of the participating centers granted authorization, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Five hundred and seventy-seven adult outpatients (282 female, 295 male, mean age 43.5 ± 12.4 years), referred to the various centers in order to undergo upper GI endoscopy, were recruited by 60 gastroenterological Italian centers.

The demographic data and clinical characteristics of the whole patient sample are shown in Table 1, according to the endoscopic findings [erosive esophagitis (EE) vs nonerosive gastroesophageal reflux (NERD)].

| PPI types and doses | Acute phase | Maintenance phase |

| Esomeprazole 40 mg | 149 (26.94) | 10 (2.16) |

| Esomeprazole 20 mg | 20 (3.62) | 141 (30.45) |

| Omeprazole 20 mg | 314 (56.78) | 33 (7.13) |

| Omeprazole 10 mg | 1 (0.18) | 211 (45.57) |

| Lansoprazole 30 mg | 13 (2.35) | 4 (0.86) |

| Lansoprazole 15 mg | 1 (0.18) | 14 (3.02) |

| Pantoprazole 40 mg | 39 (7.05) | 1 (0.22) |

| Pantoprazole 20 mg | 1 (0.18) | 35 (7.56) |

| Rabeprazole 20 mg | 15 (2.71) | 1 (0.22) |

| Rabeprazole 10 mg | 13 (2.81) |

Patients were included provided that, before endoscopic examination, the following criteria were fulfilled: (1) Age between 18 and 65 years; (2) Presence of heartburn symptoms for at least 15 d, at least once a day; (3) Referral by treating physician to a tertiary centre to undergo upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy; (4) Ability to read and write Italian, > 5 years of schooling; and (5) Consent to voluntary participation with signature on the Informed Consent form before study screening.

Patients who had one or more of these criteria at baseline were excluded from the study: (1) Treatment with PPI in the month preceding endoscopy; (2) Diagnosis of esophagitis established during the past 12 mo; (3) Pregnancy and/or lactation; and (4) Concomitant severe disease during the 4 wk preceding the study, requiring any pharmacological treatment.

Before undergoing endoscopy, patients were given a psychometric tool to assess quality of life (PGWBI-Psychological General Well Being Index) and the previously validated GERD symptom assessment questionnaire (QUID)[4].

The PGWBI is a 22-item self-administered questionnaire designed to measure perception of general wellbeing through 6 domains: anxiety (5 items), depression (3 items), feeling of wellbeing (4 items), vitality (4 items), general health (3 items) and self-control (3 items). All the items were rated on a 6-point scale (0-5). The highest possible score (110) represented the best possible wellbeing[5].

QUID is a 41-item questionnaire which investigates typical and atypical symptoms of GERD and relevant life habits for GERD. It was developed in a previous study[4] and is partially derived from an Italian validated version of GERQ (Gastroesophageal Reflux Questionnaire by Mayo Clinic[6]), in which the most relevant items were selected by means of artificial neural networks[4].

Upper GI endoscopy was performed according to the standard protocol of each participating center, and biopsy samples for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection were not universally taken, nor was there any requirement to give eradication therapy.

Esophagitis was diagnosed and graded according to the Savary Miller classification as follows[7]: Grade I-single or multiple erosions on a single fold; Grade II-multiple erosions on multiple folds; Grade III-multiple circumferential erosions; Grade IV-ulcer, stricture, and esophageal shortening.

Only omeprazole 20 mg bid was used for the initial PPI test, since the majority of studies existing in the literature at the time of study design were conducted with this drug[8-14]. The choice of therapy following the PPI test, in accordance with Genval Guidelines[2], was any available PPI at the standard dose. The same drug was subsequently used at half dose as maintenance treatment, again in accordance with Genval recommendations. In Table 1 the various PPIs used are shown with relative doses, according to the study phase. Only those patients who had a positive PPI test, defined as a reduction in heartburn severity greater than 50% at the end of the 15-d period of the test, continued the study[8,9,14]. In the case of worsening of symptoms after any reduction of dose, the participating physicians were free to resume the previous therapy. The patient could resume the treatment schedule only once during the period of the trial. Additional therapeutic step-ups were considered failure of treatment and required withdrawal from the study. Patients taking concomitant medications for medical problems other than GERD could continue therapy, and this was recorded. Patients in the study were not allowed to take any other antisecretory or prokinetic drug. Over-the-counter (OTC) antacids were allowed, if needed because of insufficient symptom control and their use was recorded.

During the 15 d of the PPI test the patient had to report daily in a diary the characteristics of heartburn in terms of intensity and frequency: intensity was scored in a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 = absent to 4 = unbearable and intolerable, with 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe. Daily average frequency was expressed simply by giving the number of daily heartburn attack. This allowed a composite heartburn score to be constructed, by multiplying the daily average frequency by the intensity.

Heartburn intensity and frequency were also assessed at the end of the acute phase (3 mo after completion of the PPI test) and after 6 mo, at the end of the study. The entire bulk of symptoms, from regurgitation to extra-esophageal concomitant manifestations were assessed by means of the QUID questionnaire only, at baseline and at the end of study, at 6 mo.

The details of the study according to the various phases are shown in Figure 1.

Of the 577 patients recruited, 306 (53%) were diagnosed with esophagitis while the remaining 271 (47%) showed no esophageal mucosal damage (Table 2). Two hundred and seventy-nine patients were smokers, 164 with EE and 115 with NERD, while 526 (289 with EE and 237 with NERD) were coffee drinkers. H. pylori status was investigated in a major subsample (454/577, 78.6%): H. pylori was found to be present in 88 patients (19.4%) and absent in 366 patients (80.6%). Eradication therapy was given in only 31 patients (16 with NERD and 15 with EE).

| EE | NERD | P | |

| (306/577, 53%) | (271/577, 47%) | ||

| Male | 194 (63.4) | 101 (37.3) | < 0.05 |

| Female | 112 (36.6) | 170 (62.7) | < 0.05 |

| Age (yr), mean (± SD) | 43.6 (± 2.22) | 43.42 (± 12.56) | NS |

| Height (cm), mean (± SD) | 169.86 (± 8.63) | 166.84 (± 8.14) | NS |

| Weight (kg), mean (± SD) | 75.33 (± 15.40) | 68.49 (± 12.41) | NS |

| Smoking | 164 (48.1) | 115 (39.2) | NS |

| Esophagitis severity (Savary-Miller classification) | |||

| Grade 1 | 237 (77.5) | - | NS |

| Grade 2 | 52 (16.9) | - | NS |

| Grade 3 | 9 (2.9) | - | NS |

| Grade 4 | 8 (2.6) | - | NS |

| H. pylori presence | 51 (14.9) | 37 (12.6 ) | NS |

| Heartburn intensity | |||

| 1 = mild | 28 (9.2) | 33 (12.1) | NS |

| 2 = moderate | 181 (59.1) | 166 (61.2 ) | NS |

| 3 = severe | 88 (28.7) | 64 (23.6) | NS |

| 4 = unbearable | 9 (2.9) | 8 (2.9) | NS |

| Regurgitation | 248 (81) | 227 (83.7) | NS |

| Chest pain | 146 (47.7) | 120 (44.3) | NS |

| Dysphagia | 99 (32.3) | 95 (35) | NS |

| Belching | 198 (64.7) | 181 (66.7) | NS |

| Chronic cough | 102 (33) | 85 (31.4) | NS |

| Hoarseness | 89 (29) | 102 (37.6) | NS |

The severity of esophagitis, assessed by the Savary-Miller classification, was as follows: grade 1 = 237 (77.5%), grade 2 = 52 (16.9%), grade 3 = 9 (2.9%), and grade 4 = 8 (2.6%).

For various reasons, as shown in Table 2, 179 patients (31%) left the study early: of these, 87 had EE and 92 had NERD. Thus 398 patients (69%) completed the entire study period (Figure 1).

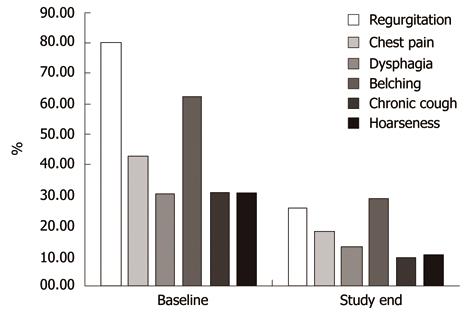

Symptoms, other than heartburn, which were evaluated by QUID questionnaire at baseline and at study completion, such as regurgitation, chest pain, dysphagia and belching, were present at baseline in percentages ranging from 83.1% for regurgitation to 33.3% for dysphagia (Table 2). Chest pain, chronic cough and hoarseness, were reported in 46.7% (296/634), 31.2% (202/634) and 33.1% (210/634) patients, respectively (Table 3).

| Dropout cause | n (%) |

| Personal reasons | 12 (6.7) |

| Therapy failure | 1 (0.6) |

| Patient fails to follow-up visit | 46 (25.7) |

| Prolonged time to visit | 60 (33.5) |

| Adverse reaction | 2 (1.1) |

| Other | 58 (32.4) |

| Total | 179 (100) |

During the 2-wk PPI test phase, 24 patients dropped out (Figure 1) and, of 553 (95.8%) patients completing the PPI test, 519 (89.9%) had a positive test, defined as a reduction in heartburn severity greater than 50% at the end of the 15-d period, and entered the acute study phase. The PPI test was positive in 224/271 (82.6%) of patients with NERD and in 295/306 (96.4%) of those with EE. The heartburn score at day 1 of the PPI test was 7.2 ± 16.09 (standard deviation) for the entire GERD population, while it was 5.94 ± 13.29 for EE patients and 8.8 ± 18.97 for NERD patients; the score was 1.37 ± 8.64, 0.86 ± 6.50 and 1.99 ± 10.67 for the entire GERD population, EE patients and NERD patients, respectively, at day 16 (trend P < 0.001). The intensity of heartburn decreased over 16 d similarly in EE (mean delta variation 0.07 ± 0.1) and NERD (mean delta variation 0.08 ± 0.09) patients.

Five hundred and nineteen patients started the acute treatment period of 3 mo, with the standard PPI dose. After 3 mo, 463 (80.2%) patients were satisfactorily treated and were admitted to the last 3-mo phase with half the PPI dose. Of these, 398 (69%) completed the full 6 mo of the study protocol (Figure 1). Corresponding figures for patients with EE after 3 mo and 6 mo were 261/577 (45.2%) and 219/577 (38%), respectively, and 202/577 (35%) and 179/577 (31%) respectively, for patients with NERD.

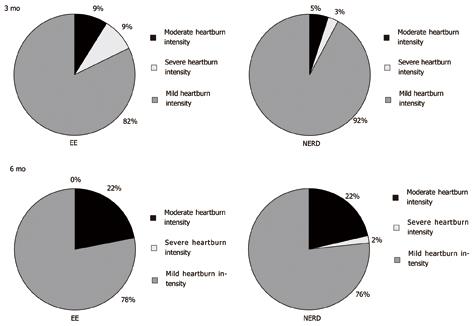

After 3 mo of acute therapy, 32/261 (12.3%) with EE and 40/202 (19.8%) NERD patients still complained of heartburn (P = 0.02), whereas after 6 mo, with half dose PPI therapy, the proportion was 27/219 (12.3%) and 45/179 (25.1%) for EE and NERD patients, respectively (P < 0.001). In other words, the percentage of completely asymptomatic patients, both at 3 and 6 mo, was significantly higher in the EE compared with NERD patients (Figure 2). The distribution of heartburn intensity among the 2 subgroups at 3 and 6 mo is shown in Figure 2.

Similarly the intensity of heartburn decreased with time differently in patients with EE and with NERD, the reduction of intensity being significantly greater in patients with EE (mean delta reduction 2.08 ± 0.77) compared with NERD patients (mean delta reduction 1.77 ± 0.83, P < 0.01).

The other GERD symptoms, such as regurgitation, chest pain, dysphagia and belching, showed a consistent and significant decrease from baseline to the final visit (Figure 3), and the same happened with the 2 most frequently reported possible extraesophageal manifestations, chronic cough and hoarseness. None of these symptoms showed a different response in NERD as compared to EE patients.

Before therapy the mean PGWBI score of our GERD population was 72.4 ± 15.62 and it rose to 84.3 ± 14.27 after the 6 mo of therapy. When compared with the mean value of a reference Italian population[15], which was 78 ± 17.89, these values were significantly different before and after therapy, and both for EE and NERD patients. In other words, the quality of life was significantly worsened by GERD symptoms before therapy and it was fully restored, even above the reference values, by the therapy. If the effect size (ES) of this change is considered, i.e. the mean change found in a given variable divided by the standard deviation (where a positive value means improvement and a negative means worsening), we found a difference in ES of -0.31 between baseline GERD and the general population before therapy, and of 0.35 between study end and the general population, without significant differences between NERD and EE patients. Among the 6 domains of PGWBI for both NERD and EE patients, it appears that anxiety and general health showed the most important variation before and after therapy. Finally, in both NERD and EE subgroups, it was apparent that the decrease in anxiety was directly related to the improvement in symptoms, in particular heartburn and nausea (data not shown).

Our study was specifically designed with the aim of assessing the validity of the Genval guidelines on GERD management in a population of patients referred for upper GI endoscopy in 60 Italian centers. In particular, we were interested in establishing, in patients with mild-to-moderate esophagitis or with NERD: (1) the symptomatic response to a brief, high dose PPI treatment as initial management; (2) whether the step-down therapeutic approach is useful to optimally balance drug cost and symptom response. As far as the first aim was concerned, the omeprazole test was used for diagnostic purposes in NERD patients only, whereas we decided to use it as a therapeutic start-up also in the EE group in order to have comparable treatments in both groups. We observed a “positive” PPI test, as defined by a reduction in heartburn severity greater than 50% at the end of the 15-d period, in 96.4% of EE patients and in 82.6% of NERD patients. The latter patients were, according to the Genval guidelines, subjects with “clinically significant impairment in quality of life due to reflux-related symptoms”, and therefore could be diagnosed as GERD patients not only in accordance with Genval[1], but also with Montreal[3] guidelines, without any need to proceed with a PPI or other diagnostic test. However, it turned out that as many as 17.4% of our NERD patients did not respond to the PPI test and for the purpose of our study were not further treated with a PPI. We do not know how many of these “non responders” could in fact still be diagnosed as GERD patients by means of esophageal pH-metry or pH-impedance monitoring, since we did not apply such tests. On the other hand, by excluding those patients with presumably non acid-related problems, we selected in a very simple way those who could better respond to PPI treatment. The figure of about 80% of patients responding to PPI, and hence categorizable as GERD patients, is in keeping with Genval statement 13, which states “When heartburn is a major or sole symptom, gastroesophageal reflux is the cause in at least 75% of individuals”. The Genval guidelines suggest, for non endoscoped patients, endoscopy-negative patients or Los Angeles grade A or B esophagitis patients, starting treatment with high dose PPI for 2-4 wk, which corresponds to our omeprazole test, and to check the symptomatic response thereafter[1]. In studies conducted on NERD patients, the PPI test has been found to have a high sensitivity but a very low diagnostic specificity[16], in particular when compared with objective measures of GERD, such as pH-metry, or with symptom questionnaires[17]. Since our NERD population was recruited on the basis of clinical diagnostic criteria (e.g. the Genval criteria) and a positive response to the PPI test, the enrolled sample may not quite be representative of the NERD population at large. On the other hand, it is more homogeneous, because it includes only the acid-related segment of the NERD spectrum, and therefore by definition excludes patients with functional heartburn (cf the Rome criteria for functional heartburn)[18]. As for the duration of the PPI test, we believe that our study proves that in GERD patients with typical symptoms, the suggestion to empirically treat with 2-4 wk of high dose PPIs[1] could be temporally limited to 1 or 2 wk, since the reduction of heartburn was already near to the maximum after the first week of high dose omeprazole administration (Figure 2).

The Genval guidelines[1] have been subsequently updated by the Marrakech recommendations[2], which however do not differ much with regard to the indications and doses of PPI therapy, and the so called PPI test, in the management of GERD patients. On the contrary, the Montreal Workshop[3] was only focused on developing a global definition and classification of GERD, but did not specifically address the issue of management.

Due to the particular design of our study, we had the opportunity to compare the subjective response to short term high dose PPI in the 2 populations of NERD and EE patients. We found an overall better response in the latter; this is, to our knowledge, a new observation, and is in keeping with the already established concept that NERD patients as a group responds less well to PPI compared with EE patients[19]. We further extended this observation by showing that NERD patients with typical symptoms, on average, show a smaller decrease in heartburn intensity also during 3-6 mo maintenance therapy with PPI compared with EE patients. We want to emphasize the point that the relatively lower symptom response rate to PPI treatment in NERD patients was not due in our study, as pointed out in the study by Dean et al[19], to the “contamination” of the NERD group by patients with functional heartburn, since our study design avoided this bias. Thus, it appears that the overall therapeutic efficacy of PPI is truly decreased in NERD as opposed to EE patients.

As far as the second aim is concerned, we have observed that the great majority of patients can be maintained symptom-free by halving the PPI dose after 15 d and 3 mo, respectively: 229/261 (87.7%) of EE and 162/202 (80.2%) of NERD patients were heartburn-free after 3 mo, respectively and 192/219 (87.7%) of EE and 134/179 (74.9%) of NERD patients after 6 mo. Again, it seems that the symptomatic response to PPI treatment is lower in NERD patients as compared to EE also during a maintenance regimen. On the other hand, this finding implies that the step-down therapy could be successfully proposed for the majority of both EE patients and NERD patients following a positive PPI test, even after a short (3-mo) period.

Finally, our study clearly confirms previous data that suggest that quality of life is greatly reduced by GERD symptoms (compared to the general population) independently of the presence or absence of esophagitis[20]. Interestingly enough, even the relatively short treatment period with PPIs in the present study (6.5 mo) was able to completely restore the quality of life in our patients, or even to improve it to levels above those showed by the general population.

In conclusion, this study is to our knowledge the first one to prospectively address relevant issues in the management of GERD outside a frame of therapeutic randomized, controlled trials. In patients with NERD or erosive esophagitis, a short period of high dose PPI (the so-called PPI test) is a valuable tool for diagnosing suspected GERD symptoms as being acid-related, and thus for selecting those patients who will benefit from PPI therapy. In the further management of these patients, 2 consecutive reductions in PPI dose are able to keep the vast majority of patients asymptomatic and to fully restore their quality of life. The overall response to PPI therapy is lower in NERD patients than in EE patients.

“The Genval Workshop Report” reviewed the existing evidence concerning gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The study aimed to test these recommendations and to assess the usefulness of a short trial of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) in the initial management and maintenance treatment on GERD patients.

The PPI test consists of measuring the symptomatic response to a high dose PPI treatment administered for 1 to 2 wk in patients with GERD symptoms and with erosive esophagitis (EE) or without it (so-called NERD). The rationale for using short-term, high dose PPI administration as a diagnostic tool is based on the strong effect of PPIs in inhibiting gastric acid secretion, healing EE and improving GERD symptoms.

This study is, to our knowledge, the first to prospectively address relevant issues in the management of GERD outside a frame of therapeutic randomized, controlled trials. In patients with NERD or EE, the PPI test is a valuable tool for diagnosing suspected GERD symptoms as being acid-related and thus for selecting those patients who will benefit from PPI therapy. In the further management of these patients, 2 consecutive reductions of PPI dose are able to keep the vast majority asymptomatic and to fully restore their quality of life. The overall response to PPI therapy is lower in NERD patients than in EE patients.

The study is one of the first trying to prospectively address relevant issues in the management of GERD outside a frame of therapeutic RCTs.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Shahab Abid, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Aga Khan University, Stadium Road, PO Box 3500, Karachi 74800, Pakistan; Dr. Limas Kupcinskas, Professor of Gastroenterology, Kaunas University of Medicine, Mickeviciaus 9, Kaunas LT 44307, Lithuania; Dr. Philip Abraham, Professor, Consultant Gastroenterologist and Hepatologist, P.D. Hinduja National Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Veer Savarkar Marg, Mahim, Mumbai 400 016, India

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management--the Genval Workshop Report. Gut. 1999;44 Suppl 2:S1-S16. |

| 2. | Dent J, Armstrong D, Delaney B, Moayyedi P, Talley NJ, Vakil N. Symptom evaluation in reflux disease: workshop background, processes, terminology, recommendations, and discussion outputs. Gut. 2004;53 Suppl 4:iv1-24. |

| 3. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. |

| 4. | Pace F, Buscema M, Dominici P, Intraligi M, Baldi F, Cestari R, Passaretti S, Bianchi Porro G, Grossi E. Artificial neural networks are able to recognize gastro-oesophageal reflux disease patients solely on the basis of clinical data. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:605-610. |

| 5. | Dupuy HJ. The Psychological General Well-being (PGWB) Index. Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies. New York: Le Jacq Publishing 1984; 170-183. |

| 6. | Locke GR, Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR. A new questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:539-547. |

| 7. | Savary M, Miller G. The esophagus: handbook and atlas of endoscopy. Solothurn (Switzerland): Verlag Gassman 1978; 119-159. |

| 8. | Fass R, Ofman JJ, Sampliner RE, Camargo L, Wendel C, Fennerty MB. The omeprazole test is as sensitive as 24-h oesophageal pH monitoring in diagnosing gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in symptomatic patients with erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:389-396. |

| 9. | Fass R, Ofman JJ, Gralnek IM, Johnson C, Camargo E, Sampliner RE, Fennerty MB. Clinical and economic assessment of the omeprazole test in patients with symptoms suggestive of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2161-2168. |

| 10. | Ofman JJ, Gralnek IM, Udani J, Fennerty MB, Fass R. The cost-effectiveness of the omeprazole test in patients with noncardiac chest pain. Am J Med. 1999;107:219-227. |

| 11. | Bate CM, Riley SA, Chapman RW, Durnin AT, Taylor MD. Evaluation of omeprazole as a cost-effective diagnostic test for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:59-66. |

| 12. | Johnsson F, Weywadt L, Solhaug JH, Hernqvist H, Bengtsson L. One-week omeprazole treatment in the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:15-20. |

| 13. | Metz DC, Childs ML, Ruiz C, Weinstein GS. Pilot study of the oral omeprazole test for reflux laryngitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116:41-46. |

| 14. | Schenk BE, Kuipers EJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Festen HP, Jansen EH, Tuynman HA, Schrijver M, Dieleman LA, Meuwissen SG. Omeprazole as a diagnostic tool in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1997-2000. |

| 15. | Grossi E, Mosconi P, Groth N, Niero M, Apolone G. IL Questionario Psychological General Well Being. Questionario per la valutazione dello stato generale di benessere psicologico. Versione Italiana. Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche "Mario Negri", Milan. 2002 . . |

| 16. | Juul-Hansen P, Rydning A. Endoscopy-negative reflux disease: what is the value of a proton-pump inhibitor test in everyday clinical practice? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1200-1203. |

| 17. | Numans ME, Lau J, de Wit NJ, Bonis PA. Short-term treatment with proton-pump inhibitors as a test for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis of diagnostic test characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:518-527. |

| 18. | Galmiche JP, Clouse RE, Bálint A, Cook IJ, Kahrilas PJ, Paterson WG, Smout AJ. Functional esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1459-1465. |

| 19. | Dean BB, Gano AD Jr, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:656-664. |

| 20. | Kulig M, Leodolter A, Vieth M, Schulte E, Jaspersen D, Labenz J, Lind T, Meyer-Sabellek W, Malfertheiner P, Stolte M. Quality of life in relation to symptoms in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-- an analysis based on the ProGERD initiative. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:767-776. |