Published online Feb 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i6.779

Revised: December 1, 2010

Accepted: December 8, 2010

Published online: February 14, 2011

AIM: To determine whether hypermagnesemia recently reported in adult patients possibly develops in children with functional constipation taking daily magnesium oxide.

METHODS: We enrolled 120 patients (57 male and 63 female) aged 1-14 years old (median: 4.7 years) with functional constipation from 13 hospitals and two private clinics. All patients fulfilled the Rome III criteria for functional constipation and were treated with daily oral magnesium oxide for at least 1 mo. The median treatment dose was 600 (500-800) mg/d. Patients were assessed by an interview and laboratory examination to determine possible hypermagnesemia. Serum magnesium concentration was also measured in sex- and age-matched control subjects (n = 38).

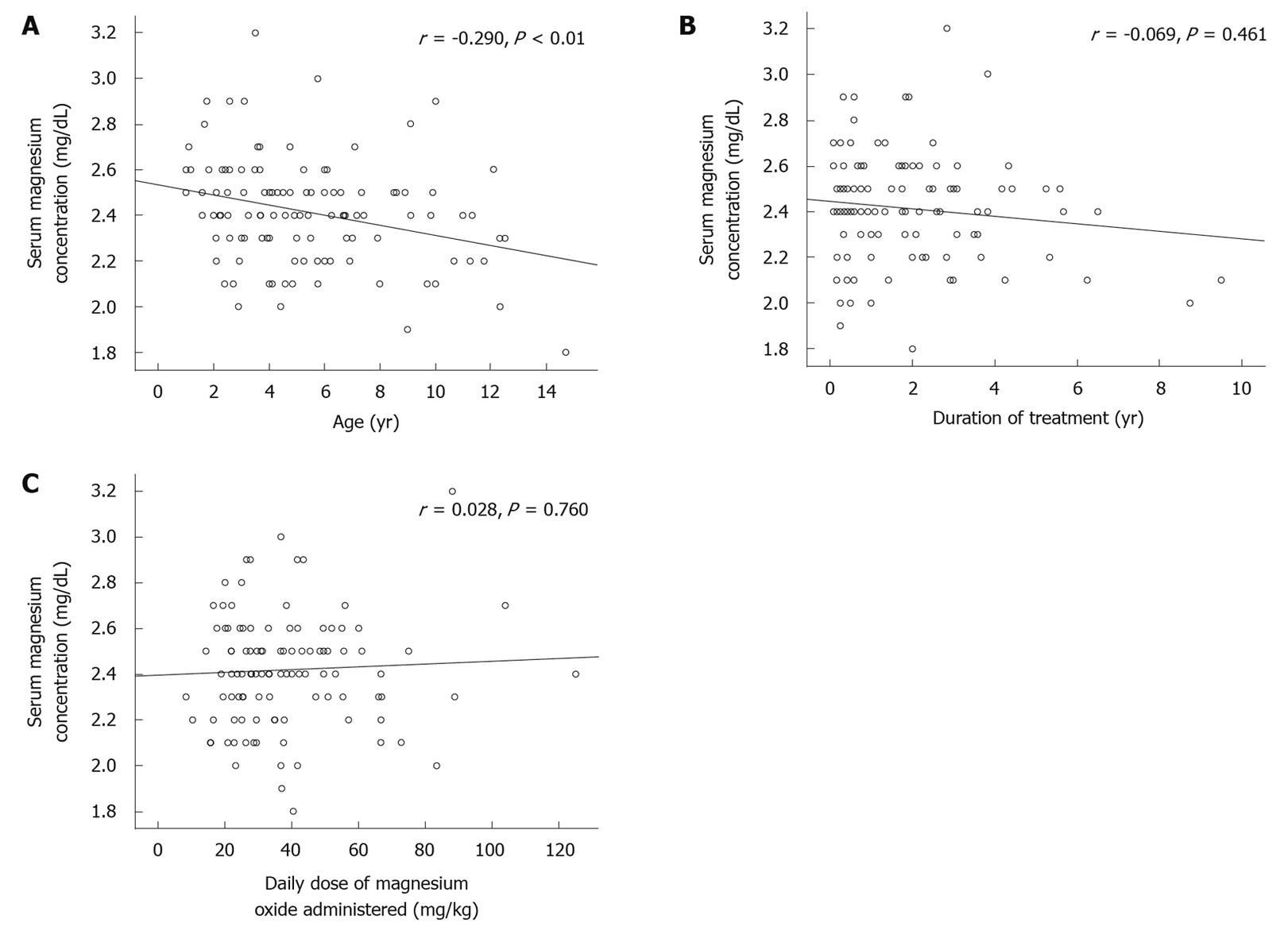

RESULTS: In the constipation group, serum magnesium concentration [2.4 (2.3-2.5) mg/dL, median and interquartile range] was significantly greater than that of the control group [2.2 (2.0-2.2) mg/dL] (P < 0.001). The highest value was 3.2 mg/dL. Renal magnesium clearance was significantly increased in the constipation group. Serum magnesium concentration in the constipation group decreased significantly with age (P < 0.01). There was no significant correlation between the serum level of magnesium and the duration of treatment with magnesium oxide or the daily dose. None of the patients had side effects associated with hypermagnesemia.

CONCLUSION: Serum magnesium concentration increased significantly, but not critically, after daily treatment with magnesium oxide in constipated children with normal renal function.

- Citation: Tatsuki M, Miyazawa R, Tomomasa T, Ishige T, Nakazawa T, Arakawa H. Serum magnesium concentration in children with functional constipation treated with magnesium oxide. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(6): 779-783

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i6/779.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i6.779

Magnesium-containing cathartics are used worldwide to treat chronic constipation[1-3]. Approximately 45 million Japanese patients are estimated to undergo treatment with magnesium oxide as an antacid or cathartic annually[4]. Many children with functional constipation are taking these drugs for long periods of time; sometimes over several years.

Hypermagnesemia is a rare clinical condition[5,6]. Most cases are iatrogenic and due to increased intake of magnesium, which occurs after intravenous administration of magnesium[7,8] or oral ingestion of high doses of magnesium-containing antacids or cathartics[9-12]. Magnesium homeostasis is dependent mainly on gastrointestinal absorption and renal excretion. The kidney is the principal organ involved in magnesium regulation. Renal magnesium excretion is very efficient, because the thick ascending limb of Henle has the capacity to reject completely magnesium reabsorption under conditions of hypermagnesemia[5,6], and therefore, hypermagnesemia commonly arises in patients with renal dysfunction.

In 2008, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) of Japan reported 15 adult patients with hypermagnesemia, including two cases of death due to oral ingestion of magnesium oxide from April 2005 to August 2008[4]. Although most of these elderly patients with constipation had dementia, schizophrenia, or renal dysfunction, the MHLW has recommended measuring the serum level of magnesium in patients who regularly use magnesium oxide.

It is now important for pediatricians to know whether hypermagnesemia can develop in children without abnormal renal function after administration of a common or high dose of magnesium oxide. The purpose of this study was to determine serum magnesium concentration in children with functional constipation treated with daily magnesium oxide.

We enrolled 120 patients (57 male and 63 female) aged 1-14 years with functional constipation from 13 hospitals and two private clinics in Japan. At entry, all patients fulfilled the Rome III criteria for functional constipation, which meant that they had at least two of the following characteristics: fewer than three bowel movements weekly; more than one episode of fecal incontinence weekly; large stools in the rectum shown by digital rectal examination or palpable on abdominal examination; occasional passage of large stools; retentive posturing and withholding behavior; and painful defecation. All patients had been treated for at least 1 mo with daily magnesium oxide as an oral laxative. The medication was given once daily or in split doses. The dose was dependent on the patient’s condition.

Children with known organic causes of constipation, including Hirschsprung disease, spinal and anal congenital abnormalities, previous colon surgery, inflammatory bowel disease, allergy, metabolic or endocrine diseases, renal dysfunction, and severe neurological disability were excluded from the study. Patients with poor drug compliance were also excluded.

In each patient, we recorded the date of initiation of constipation, daily dose of magnesium oxide, and duration of treatment. We also determined whether the patient had symptoms that could be side effects of hypermagnesemia, such as vomiting, nausea, thirst, blushing, feeling of exhaustion, or somnolence. The laboratory examinations carried out were as follows: serum level of magnesium, calcium, phosphorus, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine concentration. Urinary concentrations of magnesium and creatinine were also measured. Magnesium clearance and fractional excretion of magnesium (FEMg) were calculated as follows: Magnesium clearance = urine magnesium (mg/dL)/urine creatinine (mg/dL); FEMg = urine magnesium (mg/dL)/serum magnesium (mg/dL) × serum creatinine (mg/dL)/urine creatinine (mg/dL).

Serum magnesium concentrations were also measured in the control group which comprised 38 children (24 male and 14 female) aged 1-15 years who visited the Department of Pediatrics at Gunma University Hospital, and were without any history of hematological disease, tumor, heart failure, metabolic or endocrine diseases, renal dysfunction, or severe neurological disability. None of these children were treated with magnesium oxide.

Laboratory values, duration of treatment, and daily dose of magnesium oxide are shown as the median and interquartile ranges. Statistical significance of differences was tested by χ2 test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated for the correlation between the serum level of magnesium and age, duration of treatment, and drug dose. P < 0.05 was regarded as significant. All analyses were carried out using SPSS for Windows (SPSS statistics 17.0).

Subject characteristics and serum magnesium concentrations are shown in Table 1. In the constipation group, the median treatment duration with magnesium oxide was 1.3 (0.4-2.6) years and median daily dose was 600 (500-800) mg/d; 33 (25-45) mg/kg per day. After administration of magnesium oxide, the outcome of constipation was investigated in 83 patients. Bowel habits in all patients were improved, and 75% of patients were stable. However, 11% of children had fewer than three bowel movements weekly, 28% of them had withholding behavior, and 34% had painful defecation during the follow-up period. None of the patients still had overflow-incontinence.

The median serum magnesium concentration in the constipation group was significantly greater than that in the control group (Table 1). The highest magnesium concentration was 3.2 mg/dL in a 3.5-year-old patient treated with 1320 mg/d; 88 mg/kg per day magnesium oxide for 2.8 years.

The median urinary magnesium to creatinine ratio in the constipation group was significantly elevated compared with that reported previously [0.23 (0.15-0.37) (n = 76) vs 0.15 (0.12-0.20) (n = 16), P < 0.05)[13]. The median FEMg in the constipation group was 0.03 (0.02-0.05).

Serum magnesium concentration in the constipation group decreased significantly with age (P < 0.01) (Figure 1A). There was no significant correlation between the serum level of magnesium and duration of treatment (Figure 1B). The treatment dose had no effect on serum magnesium level (Figure 1C).

Serum level of calcium [9.9 (9.5-10.2) mg/dL], phosphorus [5.2 (4.8-5.6) mg/dL], creatinine [0.3 (0.3-0.4) mg/dL], and BUN [13.0 (10.8-15.5) mg/dL] were not abnormal in any of the patients. None of the patients had side effects associated with hypermagnesemia.

In 2008, the MHLW of Japan reported that 15 patients aged 32-98 years (median, 71 years) who had been treated with magnesium oxide developed severe side effects of magnesium toxicity, such as hypotension, bradycardia, electrocardiographic changes (atrial fibrillation), loss of consciousness, coma, respiratory depression, and cardiac arrest. The serum magnesium concentration in two fatal cases was 20.0 mg/dL and 17.0 mg/dL. As a result of these reported cases, the MHLW has recommended that the serum concentration of magnesium in subjects on continuous magnesium therapy should be determined[4].

Most cases of hypermagnesemia in adults result from large intravenous doses of magnesium[7,8] or from excessive enteral intake of magnesium-containing cathartics[9-12]. Symptomatic hypermagnesemia is likely to occur in patients with renal dysfunction. In fact, 10 of the 15 Japanese patients reported as cases of hypermagnesemia by the MHLW had renal dysfunction.

Several cases of hypermagnesemia from enteral magnesium intake in patients with normal renal function have been reported previously[14-17]. It is known that non-renal risk factors for hypermagnesemia are age, gastrointestinal tract disease, and administration of concomitant medications, particularly those with anticholinergic and narcotic effects[18]. Five elderly Japanese patients without renal dysfunction had intestinal necrosis, severe constipation, and abnormal abdominal distention with intestinal expansion, and these abdominal risk factors could have increased the serum concentration of magnesium.

Hypermagnesemia has also been reported in pediatric practice[14,19]. These case reports include a 14-year-old girl without renal dysfunction who was taking magnesium hydroxide because of severe constipation[14], and a 2-year-old boy with neurological impairments who was taking 2400 mg/d of magnesium oxide administered as part of a regimen of megavitamin and megamineral therapy[19]. These cases developed increased serum magnesium levels as high as 14.9 mg/dL and 20.3 mg/dL, respectively.

Magnesium oxide is commonly used in patients with chronic constipation; however, not only has the optimum dose for children not been established, but there has been no study to evaluate the concentration of serum magnesium after oral administration of magnesium oxide. The aim of the present study was to determine the serum magnesium concentration in pediatric cases receiving magnesium cathartics for chronic constipation.

In our study, the median serum magnesium concentration was 2.4 mg/dL in the constipation group, which was significantly greater than that in the control group (2.2 mg/dL). Thirty patients (25%) in the constipation group and none in the control group had a serum magnesium concentration greater than the maximum value of the normal range in healthy Japanese children (2.6 mg/dL). The high critical limit of serum magnesium concentration has been reported as 4.9 ± 2.0 mg/dL in adults and 4.3 ± 1.1 mg/dL in children[20]. The highest value in our study was 3.2 mg/dL, and none of our patients reached the critical limit of serum magnesium concentration or developed symptoms due to hypermagnesemia. The median urinary magnesium to creatinine ratio in the constipation group was significantly elevated compared with that in healthy subjects, which suggests that serum magnesium level is regulated by an increase in renal excretion in those children with normal renal function, and is maintained within its appropriate range.

In our study, serum magnesium level in constipated children treated with magnesium oxide, but not in the control children, decreased significantly with age. No correlation was found between duration of treatment or daily dose of magnesium oxide and serum magnesium concentration. These data are consistent with those reported by Woodard et al[21] They reported that the increase in serum magnesium concentration in 102 adults who received multiple doses of magnesium citrate did not correlate with the quantity of magnesium administered[21]. Elderly patients are at risk of magnesium toxicity as kidney function declines with age, but it is not clear whether young children have a higher risk of hypermagnesemia. Alison et al[22] reported on a 6-week-old infant who had increased serum magnesium level (14.2 mg/dL) and life-threatening apnea due to 733 mg/d magnesium hydroxide that was used to treat constipation. Brand et al[23] and Humphrey et al[24] reported on premature infants with hypermagnesemia following antacid administration in order to decrease the risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. One infant had an increased serum magnesium level of 13.3 mg/dL and developed intestinal perforation. These reports indicate that infancy, prematurity or young age might be a possible risk factor for hypermagnesemia.

According to our results, we conclude that serum magnesium concentrations increase significantly after daily magnesium oxide intake, but the magnitude of the increase appears modest. Younger age, but not prolonged use of daily magnesium oxide might be a relative risk factor, and it should be determined by further studies whether serum magnesium concentration should be assessed in these subjects.

Magnesium-containing cathartics are commonly used to treat chronic constipation. Although hypermagnesemia is a rare clinical condition, it can occur as a side effect of increased intake of magnesium salts.

The Japanese government has recently reported fatal cases of hypermagnesemia in adults treated with magnesium oxide. In our study, serum magnesium concentrations increased significantly after daily magnesium oxide intake, but the magnitude of the increase appeared modest. Serum magnesium levels in constipated children treated with magnesium oxide, but not in the control children, decreased significantly with age. No correlation was found between duration of treatment or daily dose of magnesium oxide and serum magnesium concentration.

Recent reports have highlighted that serum magnesium concentration increases significantly, but not critically, after daily treatment with magnesium oxide in children with normal renal function.

The present study indicated the safety of daily magnesium oxide treatment for children with chronic constipation.

The authors are to be congratulated for providing evidence of the apparent safety of a commonly used and effective therapy to treat an important health issue seen commonly in children.

Peer reviewer: Wallace F Berman, MD, Professor, Division of Pediatric GI/Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, Duke University Medical Center, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, Box 3009, NC 27710, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Evaluation and treatment of constipation in infants and children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:e1-e13. |

| 2. | Benninga MA, Voskuijl WP, Taminiau JA. Childhood constipation: is there new light in the tunnel? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:448-464. |

| 3. | Felt B, Wise CG, Olson A, Kochhar P, Marcus S, Coran A. Guideline for the management of pediatric idiopathic constipation and soiling. Multidisciplinary team from the University of Michigan Medical Center in Ann Arbor. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:380-385. |

| 4. | http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/iyaku_anzen/file/PMDSI252.pdf. |

| 5. | Van Hook JW. Endocrine crises. Hypermagnesemia. Crit Care Clin. 1991;7:215-223. |

| 6. | Clark BA, Brown RS. Unsuspected morbid hypermagnesemia in elderly patients. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12:336-343. |

| 7. | Morisaki H, Yamamoto S, Morita Y, Kotake Y, Ochiai R, Takeda J. Hypermagnesemia-induced cardiopulmonary arrest before induction of anesthesia for emergency cesarean section. J Clin Anesth. 2000;12:224-226. |

| 8. | Vissers RJ, Purssell R. Iatrogenic magnesium overdose: two case reports. J Emerg Med. 1996;14:187-191. |

| 9. | Schelling JR. Fatal hypermagnesemia. Clin Nephrol. 2000;53:61-65. |

| 10. | McLaughlin SA, McKinney PE. Antacid-induced hypermagnesemia in a patient with normal renal function and bowel obstruction. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:312-315. |

| 11. | Ferdinandus J, Pederson JA, Whang R. Hypermagnesemia as a cause of refractory hypotension, respiratory depression, and coma. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:669-670. |

| 13. | Mircetić RN, Dodig S, Raos M, Petres B, Cepelak I. Magnesium concentration in plasma, leukocytes and urine of children with intermittent asthma. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;312:197-203. |

| 14. | Kutsal E, Aydemir C, Eldes N, Demirel F, Polat R, Taspnar O, Kulah E. Severe hypermagnesemia as a result of excessive cathartic ingestion in a child without renal failure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:570-572. |

| 15. | Nordt SP, Williams SR, Turchen S, Manoguerra A, Smith D, Clark RF. Hypermagnesemia following an acute ingestion of Epsom salt in a patient with normal renal function. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1996;34:735-739. |

| 16. | Fassler CA, Rodriguez RM, Badesch DB, Stone WJ, Marini JJ. Magnesium toxicity as a cause of hypotension and hypoventilation. Occurrence in patients with normal renal function. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1604-1606. |

| 17. | Qureshi T, Melonakos TK. Acute hypermagnesemia after laxative use. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:552-555. |

| 18. | Fung MC, Weintraub M, Bowen DL. Hypermagnesemia. Elderly over-the-counter drug users at risk. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4:718-723. |

| 19. | McGuire JK, Kulkarni MS, Baden HP. Fatal hypermagnesemia in a child treated with megavitamin/megamineral therapy. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E18. |

| 20. | Kost GJ. New whole blood analyzers and their impact on cardiac and critical care. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1993;30:153-202. |

| 21. | Woodard JA, Shannon M, Lacouture PG, Woolf A. Serum magnesium concentrations after repetitive magnesium cathartic administration. Am J Emerg Med. 1990;8:297-300. |

| 22. | Alison LH, Bulugahapitiya D. Laxative induced magnesium poisoning in a 6 week old infant. BMJ. 1990;300:125. |

| 23. | Brand JM, Greer FR. Hypermagnesemia and intestinal perforation following antacid administration in a premature infant. Pediatrics. 1990;85:121-124. |