Published online Feb 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i6.774

Revised: September 13, 2010

Accepted: September 20, 2010

Published online: February 14, 2011

AIM: To identify optimum timing to maximize diagnostic yield by capsule endoscopy (CE) in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB).

METHODS: We identified patients who underwent CE at our institution from August 2003 to December 2009. Patient medical records were reviewed to determine type of OGIB (occult, overt), CE results and complications, and timing of CE with respect to onset of bleeding.

RESULTS: Out of 385 patients investigated for OGIB, 284 (74%) had some lesion detected by CE. In 222 patients (58%), definite lesions were detected that could unequivocally explain OGIB. Small bowel ulcer/erosions secondary to Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent use were the commonest lesions detected. Patients with overt GI bleeding for < 48 h before CE had the highest diagnostic yield (87%). This was significantly greater (P < 0.05) compared to that in patients with overt bleeding prior to 48 h (68%), as well as those with occult OGIB (59%).

CONCLUSION: We established the importance of early CE in management of OGIB. CE within 48 h of overt bleeding has the greatest potential for lesion detection.

- Citation: Goenka MK, Majumder S, Kumar S, Sethy PK, Goenka U. Single center experience of capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(6): 774-778

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i6/774.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i6.774

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) is responsible for about 5% of all gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding[1]. Although it represents a small proportion of patients with GI bleeding, OGIB continues to be a challenge because of delay in diagnosis and consequent morbidity and mortality. In recent times, capsule endoscopy (CE) and device-assisted enteroscopy have established their position in the management algorithm for OGIB, and have had a significant impact on the outcome. CE is superior to push enteroscopy[2,3], small bowel follow-through[4] and computed tomography (CT)[5] for detection of the bleeding source in the small bowel. There is however concern about sensitivity of CE in the setting of ongoing GI bleeding, due to possible visualization of blood limiting the interpretation. Most published reports on CE in OGIB are limited to small groups of patients[6-8]. Although most differentiate between occult and overt GI bleeding when analyzing diagnostic yield, they do not identify the optimum time for performing CE in the overt GI bleeding group. We evaluated the diagnostic yield of CE in identifying the source of bleeding in OGIB. We further analyzed our patients to answer the question regarding proper timing of performing CE in overt OGIB, to maximize diagnostic yield. To the best of our knowledge, the present study of 385 patients with OGIB is the largest single-center experience of CE in OGIB.

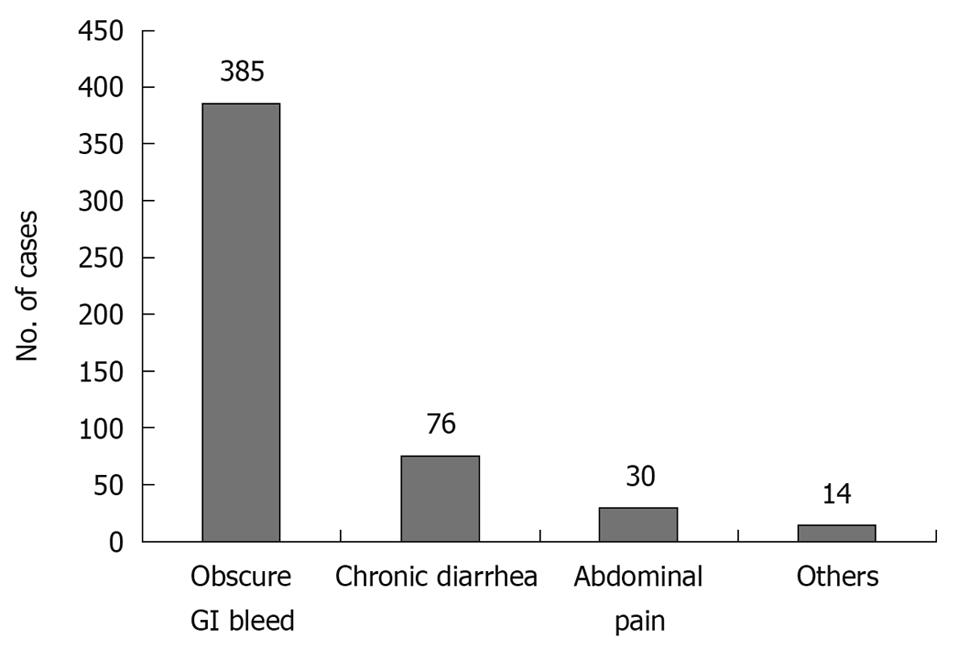

Patients who presented with evidence of GI bleeding at the clinic or emergency department were enrolled in the present study after negative upper GI endoscopy and full-length colonoscopy. Between August 2003 and December 2009, 505 patients underwent CE at our center. 345 patients underwent the procedure as inpatients, whereas 160 were outpatients. Of these, 385 (76.2%) had CE for OGIB (Figure 1). Patients with OGIB were further classified into three categories: (1) persistent overt bleeding, i.e. bleeding documented within 48 h at the time of first evaluation; (2) recent overt bleeding, i.e. last episode of bleeding > 48 h prior to the first evaluation; and (3) obscure occult bleeding, i.e. anemia associated with positive fecal occult blood without overt bleeding.

The GIVEN Video Capsule system (Given Imaging, Yoqneam, Israel) was used with M2A/SB capsules. The reader system was updated during the study period from Rapid 3 to Rapid 5. The real time viewer (Given Imaging) was used during the final 6 mo of the study. Patients were allowed a light diet on the previous evening and were prepared by using an oral purge at night (2 L polyethylene-glycol-based solution or 90 mL sodium phosphate mixed with 350 mL lime-based drink followed by 1 L water). Patients swallowed the capsule between 09:00 and 11:00 h, and were maintained on nil by mouth for the next 4 h. Six patients had swallowing difficulty and had their capsule delivered into the stomach using an endoscope with the help of an AdvanCE device. Patients with known diabetes mellitus and history of vomiting that was suggestive of gastroparesis were given two doses of intravenous metoclopramide (10 mg) during the study. Intravenous metoclopramide was also given to three of 40 patients who were found to have their capsule in the stomach on real time study, even at 2.5 h after capsule ingestion. The recorder of CE was disconnected only after the battery stopped blinking at 8-11 h after capsule ingestion. Only one procedure had technical difficulty with the capsule not becoming active after removal from the container, and had to be replaced with another capsule. All other patients had a smooth examination.

The interpretation of images was done by a single gastroenterologist (MKG) after initial detailed evaluation by a trained technician who had been involved in > 50 000 GI endoscopic procedures. Findings were categorized as definite, suspicious or negative as follows: (1) definite: lesions with definite bleeding potential that clearly explained the clinical situation; (2) suspicious: mucosal lesions identified, but bleeding could not be conclusively attributed to them, or blood was seen in the small intestine without any definite lesion being identified; and (3) negative: no lesion or bleeding identified, or incomplete study.

Patients were asked to note evacuation of the capsule, and those who were uncertain or concerned, as well as those who were suspected to have retained the capsule, as suggested by capsule image interpretation, were followed by serial X-ray/fluoroscopic screening at weekly intervals. Patients were also followed up with medical therapy (such as treatment of Crohn’s disease, institution of antitubercular therapy, or antihelminthic therapy), surgical therapy (for tumors or bleeding ulcers) or enteroscopic evaluation (ulcers, polyps, or bleeding angiodysplasia), depending on the CE results. Those with negative CE were followed up with expectant treatment or surgery with preoperative enteroscopy. The study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statistical methods included χ2 analysis for comparison of the positive diagnostic yield of CE between the three different categories of OGIB. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

OGIB was the commonest (76.2%) indication for CE during the study period (Figure 1). Out of the 385 patients with OGIB, 275 (71%) were male with age ranging from 12 to 80 years. One hundred and one patients (26.2%) had a negative examination, either because no obvious lesion was found until the small intestine (n = 93) or because the progress was slow (n = 8). Of the eight patients with slow progress of the capsule, six had diabetes mellitus. Of the 101 patients with negative CE, nine underwent laparotomy because of recurrent/persistent bleeding, and in eight, some lesion was found at preoperative enteroscopy (Meckel’s diverticulum, 1; small-intestinal ulcers, 3; and angiodysplasia, 4). One patient had negative laparotomy. Of the remaining 92 patients in this group, only 52 were available for a follow-up of 1 year and none had any significant bleeding.

Two hundred and eighty-four patients (73.8%) had some lesion detected at CE. Although 272 of these lesions were located in the small intestine, 12 (ulcers/erosions, 8; angiodysplasia, 3; and gastric fundal tumor, 1) had findings in the stomach/duodenum that were missed at pre-CE gastroscopy. Two hundred and twenty-two patients (57.7%) were considered to have definite lesions that could explain OGIB, whereas another 62 (16.1%) had lesions that were suspicious but bleeding could not be completely attributed to these findings. The latter included 32 patients with small ulcers and erosions, seven with doubtful angiodysplasia, eight with worms (3 roundworm, 3 whipworm, and 2 hookworm) and 15 patients with blood in the jejunum or ileum, without any underlying lesion being identified. Four of these patients with evidence of bleeding but no underlying lesions underwent mesenteric angiography that also detected bleeding, but no obvious pathology was found and bleeding stopped with supportive treatment alone.

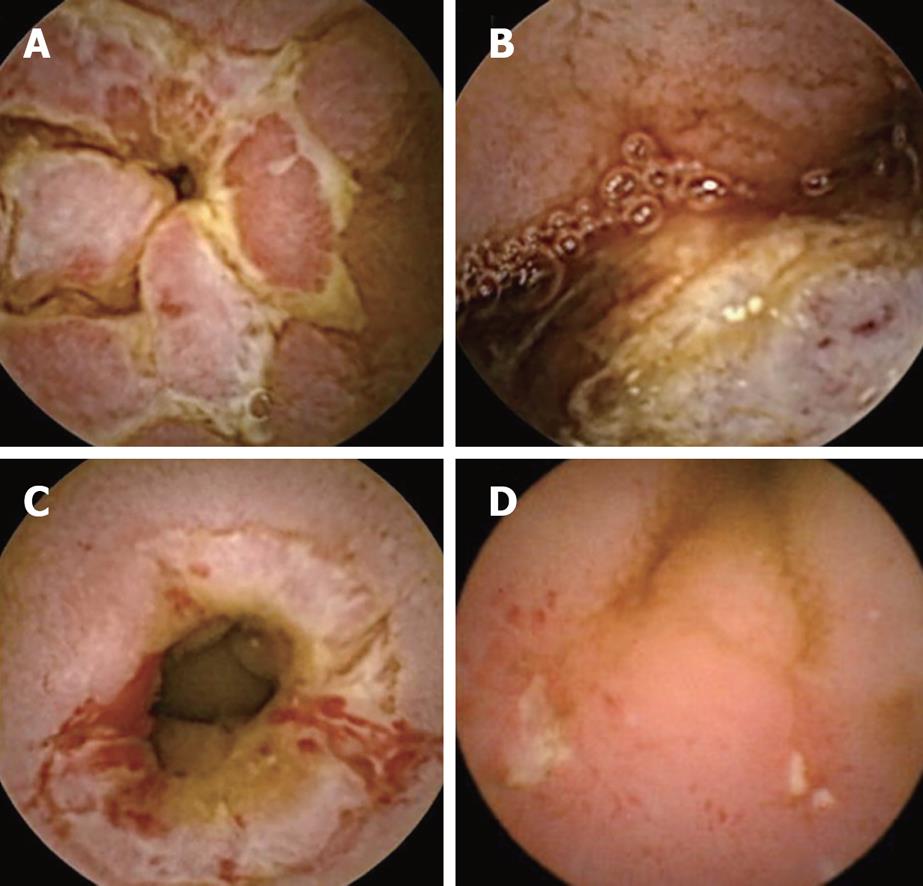

As demonstrated in Table 1, the 222 patients with definite lesions at CE included ulcers/erosions in 156, tumors in 48, and angiodysplasia in 18. Among those with tumors, two had multiple polyps that were suggestive of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. It was difficult to characterize ulcers/erosions, but at least 12 were considered to be tubercular (based on abdominal CT scan ± fine needle aspiration cytology and follow-up), 42 patients were considered to have Crohn’s disease (based on fissuring serpiginous ulcers with cobble-stone appearance, or histology from tissue obtained at enteroscopy or surgery), and 12 were nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced. Of the 18 patients with arteriovenous malformation (AVM), four underwent double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE), three had successful treatment with argon plasma coagulation, and the others were put on hormonal therapy/tranexamic acid.

| Definite (n = 222) | Suspicious (n = 62) | Total (n = 284) | |

| Ulcers/erosions | 156 | 32 | 188 |

| Tumor | 48 | 0 | 48 |

| AVM | 18 | 7 | 25 |

| Worms | 0 | 8 | 8 |

| Only blood | 0 | 15 | 15 |

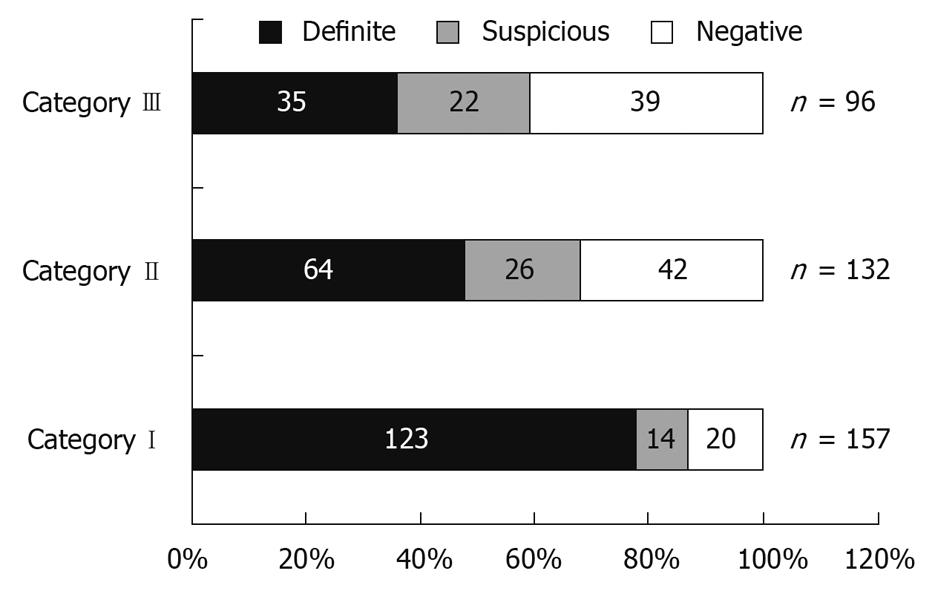

Figure 2 shows the distribution of patients according to category of bleeding. In patients with ongoing bleeding (Category I), positive findings were seen in 87.2% (definite in 78.3%), whereas in patients with previous overt bleeding (Category II), it was 68.2% (definite in 48.5%), and in the occult OGIB group (Category III), only 59.3% (definite in 36.4%). The ability of CE to identify a definite bleeding source was significantly higher for Category I than Category II and III patients (P < 0.05), but there was no significant difference in the diagnostic yield when comparing Category II and III patients (Figure 3).

Capsule retention was noted in six of 385 patients (1.6%). All these patients had strictures in the small bowel either due to tuberculosis or Crohn’s disease, which were not suspected or identified prior to CE. Three of these patients underwent surgery, two were lost to follow-up, and one refused surgery and continues to have capsule retention, but has been asymptomatic during follow-up of 9 mo.

CE has gained widespread clinical acceptance in the diagnostic algorithm of OGIB[9,10]. As in our study, OGIB is now the leading indication for CE in most centers around the world. Prior to the introduction of CE, barium examination, push enteroscopy and angiography were the principle diagnostic tools for OGIB. The diagnostic yield of these tests has been shown to be unequivocally inferior to CE in several studies. Recently, DBE has been used in several centers for diagnosis of OGIB. However, diagnostic yield of CE has been found to be significantly higher compared to a single DBE examination done via the oral or anal route (137/219 vs 110/219, OR: 1.67, 95% CI: 1.14-2.44, P < 0.01)[11].

The reported yield of CE in OGIB varies widely. Previous studies have shown that detection rates for the source of bleeding varies from 38% to 93%, and is in the higher range for those with overt OGIB[9,10]. This is further influenced by subjective interpretation of positive findings. To address this issue in our study, we divided positive findings into definite and suspicious groups. Although the overall diagnostic yield in our study cohort was 73.8%, a definite lesion that could explain OGIB was obtained in only 57.7%. A recently published study by Hindryckx et al[8] which considered CE to be positive only when lesions with sufficient bleeding potential were detected, reported a similar diagnostic yield of 59.8%.

Recent studies have indicated that the optimum timing of CE in OGIB is within the first few days, with acceptable maximum duration of 2 wk[13-17]. In a recently reported series of 260 patients with OGIB, the yield was 87% in patients with ongoing overt OGIB and 46% in those with occult OGIB[10]. In our patients, a definite lesion could be detected in 64.7% of patients with overt OGIB compared to 36.4% in patients with occult OGIB (P < 0.01). Moreover, the diagnostic yield of CE was significantly higher in patients who had evidence of bleeding within 48 h of CE (Category I) compared to those who had remote overt bleeding (Category II) [123/157 (78.3%) vs. 64/132 (48.5%) OR: 3.84, 95% CI: 2.31-6.41, P < 0.01, respectively]. The diagnostic yield of CE was not significantly different when comparing patients with remote overt OGIB (> 48 h before CE) (Category II) and those with occult OGIB (Category III). This highlights the importance of using CE early in the diagnosis of OGIB. Pennazio et al also have found the highest yield in patients with ongoing GI bleeding, and therefore have recommended ordering CE earlier in the setting of overt OGIB. There have been concerns in the past regarding the possibility of blood obscuring proper visualization of the mucosa in patients who are actively bleeding. A recent study that has compared massively bleeding patients with chronic overt OGIB has found a similar positive yield in both groups [59.18% (29/49) and 52.69% (137/260), respectively][18]. These results demonstrate that, for optimum diagnostic efficacy, CE should be done within 48 h of bleeding in patients with OGIB.

The definition of a positive finding on CE continues to be ambiguous. For the purpose of this study, nonspecific mucosal changes such as red spots, focal erythema and fold thickening, were not considered to be clinically significant. Ulcers and erosions were included as positive findings in this series if they could completely or partially account for the GI bleeding. Moreover, active bleeding without definite lesions was described as a suspicious finding in this study. The commonest lesion detected in our patients was small-bowel ulcers and erosions, followed by tumors and AVM. A previous study from India also has documented small-bowel ulcers to be the commonest lesion detected by CE in OGIB[19]. A definite underlying etiology could be established in 66 (42.3%) out of the 156 patients with ulcers/erosions, and nearly two-thirds (42/66) of them were considered to be due to Crohn’s disease.

The current study has several limitations. In the first place it is a retrospective single-center study. However data was obtained from forms filled at the time of CE, thereby minimizing data collection bias. Secondly this study does not offer long-term follow-up of the patients and hence makes it impossible to draw a strong conclusion as to the fate of CE-negative OGIB. Moreover a large proportion of ulcers/erosions could not be characterized due to inherent difficulty of obtaining small bowel mucosal biopsies. However, this study enabled us to analyze positivity rates, nature of lesions and optimum timing of CE in a relatively large cohort of subjects comprising of a heterogeneous population of patients with OGIB. Although the data demonstrates the diagnostic utility of early CE in OGIB it does not reflect whether an early diagnostic intervention and unequivocal identification of a bleeding source affects clinical outcome in this group of patients.

In summary, high diagnostic yield, relative safety and tolerability have established CE as an important diagnostic tool for OGIB. In this large cohort of OGIB patients, we demonstrate that small bowel ulcer/erosions secondary to Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis or NSAID-use are the commonest lesions responsible for OGIB in this part of the world. Moreover, the diagnostic yield is significantly affected by the timing of CE and studies done within 48 h of an episode of overt bleed have the greatest potential for detecting a definite lesion.

The advent of video capsule endoscopy (CE) has resulted in a paradigm shift in the approach to the diagnosis and management of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleed (OGIB). With increasing global availability of this diagnostic tool, it has now become an integral part of the diagnostic algorithm for OGIB in most parts of the world. However there is scant data on optimum timing of CE for maximizing diagnostic yield. OGIB continues to be a challenge because of delay in diagnosis and consequent morbidity and mortality.

Previous studies have shown that capsule endoscopy detection rates for the source of bleeding varies from 38% to 93%, being in the higher range for those with overt OGIB. Results in most studies are further influenced by subjective interpretation of “positive findings”. The authors classified our patients depending on time since last episode of bleed and looked at diagnostic yield in the different groups with the aim to identify a time-frame to guide clinical decision-making on when to do a capsule endoscopy in this cohort of patients.

Diagnostic yield is significantly affected by the timing of CE and studies done within 48 h of an episode of overt bleed have the greatest potential for detecting a definite lesion. The diagnostic yield of CE was not significantly different when comparing patients with overt OGIB prior to 48 h of CE and those with occult OGIB. This highlights the importance of obtaining a CE early in the diagnosis of OGIB.

This article suggests a potential benefit of doing a capsule endoscopy within 48 h of an episode of bleed in patients with OGIB in terms of increasing chances of detecting a bleeding source. However, further studies are needed to determine if early detection of lesion translates into better patient outcome.

The paper provides well-collected information about early detection of small intestinal lesions by CE in obscure GI bleed. Research should be aimed at finding if early detection results in improved patient outcome.

Peer reviewer: Andrew Ukleja, MD, Assistant Professor, Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of Nutrition Support Team, Director of Esophageal Motility Laboratory, Cleveland Clinic Florida, Department of Gastroenterology, 2950 Cleveland Clinic Blvd., Weston, FL 33331, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Cellier C. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: role of videocapsule and double-balloon enteroscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:329-340. |

| 2. | Ell C, Remke S, May A, Helou L, Henrich R, Mayer G. The first prospective controlled trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2002;34:685-689. |

| 3. | Lim RM, O’Loughlin CJ, Barkin JS. Comparison of wireless capsule endoscopy (M2A™) with push enteroscopy in the evaluation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:S83. |

| 4. | Costamagna G, Shah SK, Riccioni ME, Foschia F, Mutignani M, Perri V, Vecchioli A, Brizi MG, Picciocchi A, Marano P. A prospective trial comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:999-1005. |

| 5. | Hara AK, Leighton JA, Sharma VK, Fleischer DE. Small bowel: preliminary comparison of capsule endoscopy with barium study and CT. Radiology. 2004;230:260-265. |

| 6. | Tang SJ, Christodoulou D, Zanati S, Dubcenco E, Petroniene R, Cirocco M, Kandel G, Haber GB, Kortan P, Marcon NE. Wireless capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: a single-centre, one-year experience. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:559-565. |

| 7. | Esaki M, Matsumoto T, Yada S, Yanaru-Fujisawa R, Kudo T, Yanai S, Nakamura S, Iida M. Factors associated with the clinical impact of capsule endoscopy in patients with overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2294-2301. |

| 8. | Hindryckx P, Botelberge T, De Vos M, De Looze D. Clinical impact of capsule endoscopy on further strategy and long-term clinical outcome in patients with obscure bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:98-104. |

| 9. | Pennazio M, Eisen G, Goldfarb N. ICCE consensus for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1046-1050. |

| 10. | Mishkin DS, Chuttani R, Croffie J, Disario J, Liu J, Shah R, Somogyi L, Tierney W, Song LM, Petersen BT. ASGE Technology Status Evaluation Report: wireless capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:539-545. |

| 11. | Chen X, Ran ZH, Tong JL. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with small bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4372-4378. |

| 12. | Tang SJ, Haber GB. Capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2004;14:87-100. |

| 13. | Carey EJ, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK, Post JK, Fleischer DE. A single-center experience of 260 consecutive patients undergoing capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:89-95. |

| 14. | Rey JF, Ladas S, Alhassani A, Kuznetsov K. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE). Video capsule endoscopy: update to guidelines (May 2006). Endoscopy. 2006;38:1047-1053. |

| 15. | Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini FP, De Franchis R. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:643-653. |

| 16. | Bresci G, Parisi G, Bertoni M, Tumino E, Capria A. The role of video capsule endoscopy for evaluating obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: usefulness of early use. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:256-259. |

| 17. | Ge ZZ, Chen HY, Gao YJ, Hu YB, Xiao SD. Best candidates for capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:2076-2080. |

| 18. | Zhang BL, Fang YH, Chen CX, Li YM, Xiang Z. Single-center experience of 309 consecutive patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5740-5745. |

| 19. | Gupta R, Lakhtakia S, Tandan M, Banerjee R, Ramchandani M, Anuradha S, Ramji C, Rao GV, Pradeep R, Reddy DN. Capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding--an Indian experience. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:188-190. |