Published online Feb 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i5.639

Revised: November 2, 2010

Accepted: November 9, 2010

Published online: February 7, 2011

AIM: To study the natural history and prevalence of heartburn at a 10-year interval, and to study the effect of heartburn on various symptoms and activities.

METHODS: A population-based postal study was carried out. Questionnaires were mailed to the same age- and gender-stratified random sample of the Icelandic population (aged 18-75 years) in 1996 and again in 2006. Subjects were classified with heartburn if they reported heartburn in the preceding year and/or week, based on the definition of heartburn.

RESULTS: Heartburn in the preceding year was reported in 42.8% (1996) and 44.2% (2006) of subjects, with a strong relationship between those who experienced heartburn in both years. Heartburn in the preceding week was diagnosed in 20.8%. There was a significant relationship between heartburn, dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome. Individuals with a body mass index (BMI) below or higher than normal weight were more likely to have heartburn. Heartburn caused by food or beverages was reported very often by 20.0% of subjects.

CONCLUSION: Heartburn is a common and chronic condition. Subjects with a BMI below or higher than normal weight are more likely to experience heartburn. Heartburn has a great impact on daily activities, sleep and quality of life.

- Citation: Olafsdottir LB, Gudjonsson H, Jonsdottir HH, Thjodleifsson B. Natural history of heartburn: A 10-year population-based study. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(5): 639-645

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i5/639.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i5.639

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most prevalent diseases worldwide[1]. GERD is a chronic condition which usually manifests symptomatically, is a great burden for patients, and has significant socioeconomic implications[2]. The prevalence of predominant gastroesophageal reflux symptoms appears to be stable over time[3]. Heartburn is the typical GERD symptom and may be induced by various physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms[4]. Heartburn, coupled with acid regurgitation and odynophagia, are considered to be highly specific for GERD[1].

Functional heartburn is defined as episodic retrosternal burning in the absence of GERD, histopathology-based motility disorders or structural explanations[5]. Heartburn alone has a prevalence of 17%-42% in Western populations[2,3,5-7].

The prevalence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population is high and symptoms are associated with significant health-care utilization and diminished quality of life[6]. In contrast, the natural history of heartburn has received limited attention and few epidemiological studies have focused on heartburn. Subjects with upper gastrointestinal symptoms are more likely to use prescription medication and are more likely to have seen a physician about symptoms than those with heartburn[6]. There has been more focus on GERD than heartburn.

The aim of this present study was therefore to evaluate the natural history of heartburn in the Icelandic population prospectively over a 10-year period, as well as to evaluate different factors which are affected by heartburn both physically and sociodemographically. A parallel publication based on the same database, focusing on functional dyspepsia (FD), has been published[8] as has another parallel publication regarding irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)[9].

In 1996 an epidemiological study of gastrointestinal diseases was carried out in Iceland[10], involving 2000 inhabitants in the range of 18-75 years of age. The individuals were randomly selected from the National Registry of Iceland. Equal distribution of sex and age was secured in each age group. In 2006 we attempted to contact all the same individuals as in 1996 as well as adding 300 new individuals in the 18-27 age group who were also randomly selected from the National Registry. A study questionnaire and explanatory letter were mailed to all eligible individuals at baseline. Reminder letters were mailed at 2, 4 and 7 wk, using the Total Method of Dillman[11]. Individuals who indicated at any point that they did not want to participate in the study were not contacted further.

The Bowel Disease Questionnaire (BDQ)[12,13] was translated and modified for this study. The questionnaire was designed as a self-report instrument to measure symptoms experienced over the previous year and to collect the subject’s past medical history[14].

The Icelandic version of the BDQ questionnaire addresses 47 gastrointestinal symptoms and 32 items that measure past illness, health care use, items on sociodemographic and psychosomatic symptoms, together with a valid measure of non-gastrointestinal (non-GI) somatic complaints ascertained through the Somatic Symptom Checklist (SSC)[15]. The SSC includes questions on 12 non-GI and 5 GI symptoms or illnesses. Individuals are instructed to indicate, on a 5-point scale, how often each symptom has appeared and how bothersome it has been. There were few changes to the later questionnaire (2006) which addressed 51 gastrointestinal symptoms and 33 items that measure past illness, health care use, and sociodemographic and psychosomatic symptoms items. The 2006 Questionnaire furthermore addressed 17 items to identify heartburn and items related to heartburn.

Subjects were classified with heartburn if they reported heartburn according to the following definition: Heartburn is a burning sensation in the retrosternal area (behind the breastbone). The pain often rises in the upper abdomen and may radiate to the chest.

A transition model used by Halder et al[14] was modified and applied for this study. The responses from the initial (1996) and final (2006) surveys were matched for each subject to examine the changes between disorders at an individual level for the 5 categories (FD, IBS, heartburn, frequent abdominal pain and no symptoms). A 5 × 5 table was used to model these multiple changes and collapsed into 6 groups, as illustrated in Table 1. Those with the most symptoms were prioritized higher. Those who developed more symptoms and those who reported fewer symptoms could be categorized into their respective groups. There were six patterns of symptoms, identified as follows: (1) symptom stability; (2) symptom increase; (3) symptom decrease; (4) symptom onset; (5) became asymptomatic; and (6) none of these symptoms.

| FGID in 1996 | Proportion of FGID in 2006 based on primary survey disorder (%) | ||||

| FD | IBS | Heartburn | Frequent abdominal pain | No symptoms | |

| FD (n = 111) | 52.31 | 21.63 | 14.43 | 1.83 | 9.94 |

| IBS (n = 152) | 25.02 | 30.31 | 19.73 | 4.63 | 20.44 |

| Heartburn (n = 173) | 12.12 | 12.12 | 39.31 | 4.63 | 31.84 |

| Frequent abdominal pain (n = 39) | 12.82 | 23.12 | 17.92 | 15.41 | 30.84 |

| No symptoms (n = 324) | 3.45 | 9.95 | 17.35 | 6.25 | 63.36 |

For the 2006 survey we identified all deceased individuals with the assistance of the National Registry of Iceland (Thjodskra).

Tables were constructed to show frequency and percentage. Categorical data were analyzed using the χ2 test. The type I error protection rate was set at 0.05. The exact P is listed in the tables and text. All the research data were imported into SPSS (Statistical Package of Social Science) software.

The National Bioethics Committee of Iceland and The Icelandic Data Protection Authority (Personuvernd) gave their permission for the research.

In 1996 the response rate was 66.8% (1336/2000). Of the 1336 individuals who participated in 1996, 81 were deceased by 2006, five subjects were unable to answer, mainly because of old age, and 70 could not be traced to a current address. This left 1180 individuals, out of whom 799 responded. Therefore, the response rate in 2006 was 67.7% (799/1180). The mean age of the individuals in 1996 was 42 years, in 2006 it was 43 years, and 41 years for non-respondents in 2006. Women were more likely to respond than men in both years. A larger proportion of women than men responded again in 2006 (57.8%) than had responded in 1996, as is common in similar studies. The responders represented the population in all major factors concerning sex and age distribution. The response rate was also higher for older subjects than for younger ones. The age distribution and demographic details of the study cohort are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

| Population 2006 (%) | Respondents 2006 (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 50.3 | 42.2 |

| Female | 49.7 | 57.8 |

| Age (yr) | ||

| 28-35 | 19.5 | 14.52 |

| 36-45 | 24.9 | 20.40 |

| 46-55 | 22.8 | 22.15 |

| 56-65 | 15.6 | 19.52 |

| 66-75 | 10.4 | 15.14 |

| 76-85 | 6.8 | 8.26 |

| Total number | 173 859 | 799 |

| n | Never HB (%) | Lost HB (%) | Retained HB (%) | Developed HB (%) | χ2 | P-value | |

| Gender | 1.687 | 0.640 | |||||

| Male | 330 | 40.3 | 14.5 | 30.3 | 14.8 | ||

| Female | 441 | 41.5 | 14.7 | 26.5 | 17.2 | ||

| Age group (yr) | 15.542 | < 0.05a | |||||

| 66-85 | 170 | 54.8 | 10.6 | 27.1 | 10.6 | ||

| 36-65 | 488 | 37.3 | 16.4 | 29.3 | 17.0 | ||

| 28-35 | 113 | 40.7 | 13.3 | 24.8 | 21.2 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.685 | < 0.01b | |||||

| > 30 | 154 | 31.8 | 14.3 | 37.0 | 16.9 | ||

| > 25 and ≤ 30 | 314 | 37.3 | 14.3 | 31.5 | 16.9 | ||

| ≤ 25 | 286 | 49.3 | 15.0 | 19.9 | 15.7 | ||

| Level of education | 6.156 | 0.724 | |||||

| > 4 years’ further education | 225 | 39.6 | 12.9 | 28.9 | 18.7 | ||

| 3-4 years’ further education | 279 | 41.9 | 17.6 | 25.1 | 15.4 | ||

| < 3 years’ further education | 92 | 39.1 | 13.0 | 33.7 | 14.1 | ||

| No further education | 161 | 41.6 | 13.0 | 29.8 | 15.5 | ||

| Employment status | 6.276 | 0.099 | |||||

| Employed | 574 | 39.7 | 15.5 | 27.0 | 17.8 | ||

| No employment | 189 | 44.4 | 12.2 | 31.7 | 11.6 | ||

| Alcohol | 4.503 | 0.609 | |||||

| ≥ 7 drinks per week | 43 | 37.2 | 9.3 | 34.9 | 18.6 | ||

| 1-6 drinks per week | 404 | 39.1 | 14.6 | 28.2 | 18.1 | ||

| No alcohol | 309 | 43.0 | 15.5 | 27.5 | 13.9 | ||

| Smoking | 8.773 | 0.187 | |||||

| Smokers, > 15 cigarettes per day | 63 | 34.9 | 20.6 | 25.4 | 19.0 | ||

| Smokers, ≤ 15 cigarettes per day | 113 | 31.9 | 17.7 | 34.5 | 15.9 | ||

| No smoking | 496 | 43.5 | 13.7 | 26.2 | 16.5 |

At the 10-year follow-up, individuals were asked if they had experienced heartburn in the preceding year; 42.8% in 1996 and 44.2% in 2006 reported heartburn. There was a strong relationship between those who experienced heartburn in 2006 and those who reported heartburn in 1996. Two thirds of those who reported heartburn in 1996 also experienced heartburn in 2006. However, one third of those who reported heartburn in 2006 had not experienced it 10 years earlier.

Almost all who were on medication for heartburn reported relief with the medication. Individuals reported acid reflux once a month or more in 11% of cases in 1996 and 10% of cases in 2006.

There was a significant relationship between heartburn and dyspepsia and between heartburn and IBS, both in 1996 and in 2006.

Individuals of normal weight [body mass index (BMI) 18.5-24.9] were less likely to experience heartburn than individuals with a BMI below or higher than normal weight.

Individuals who smoked were not more likely to have heartburn than those who did not smoke. Individual alcohol consumption within the study group changed during the 10-year period of 1996 to 2006. Alcohol consumption was not associated with heartburn.

As described in the Methods section, the groups in this analysis were defined as mutually exclusive using a symptom hierarchy so that each subject appears in only one category for both the 1996 and 2006 surveys. There was a “no symptoms” category for those who did not meet any of the criteria applied for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Due to the hierarchical classification only a few participants occurred in some categories.

There was a substantial change in numbers in all the categories over time (Table 1). The group “no symptoms” was the most common (63.3%). Of the heartburn group 39.3% were stable and 31.8% reported “no symptoms”; 24.2% reported increased symptoms and 4.6% decreased symptoms. Of the FD group 52.3% remained stable and 9.9% reported “no symptoms” in 2006. Most of the subjects who were in the IBS group, or 30.3% of the total, were stable over the 10-year period; 20.4% reported “no symptoms” in 2006 and 25.0% showed an increase in symptoms over the 10 years. In 2006, 15.4% of the subjects reported stable frequent abdominal pain, 30.8% reported “no symptoms” and 53.8% reported increased symptoms.

The distribution of the 6 transition groups was: 22.3% symptom stability, 12.6% symptom increase, 10.9% symptom decrease, 14.9% developed symptoms, 13.6% became asymptomatic, and 25.7% had no symptoms in either 1996 or 2006.

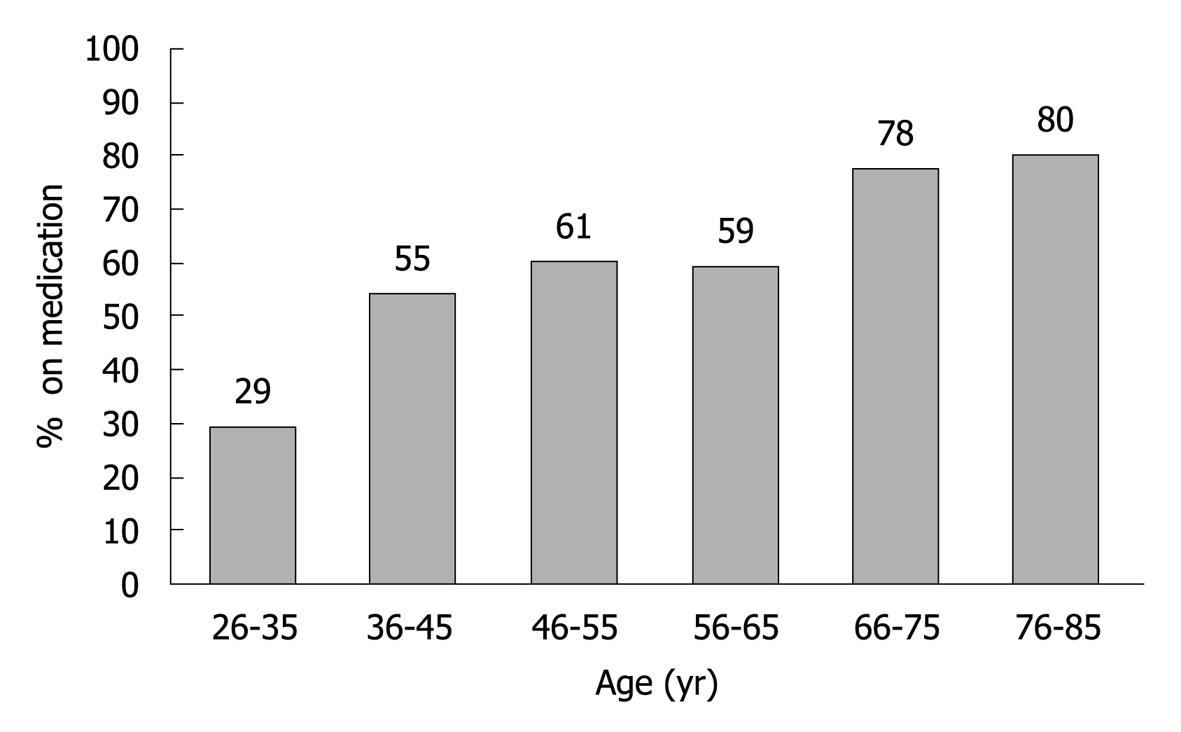

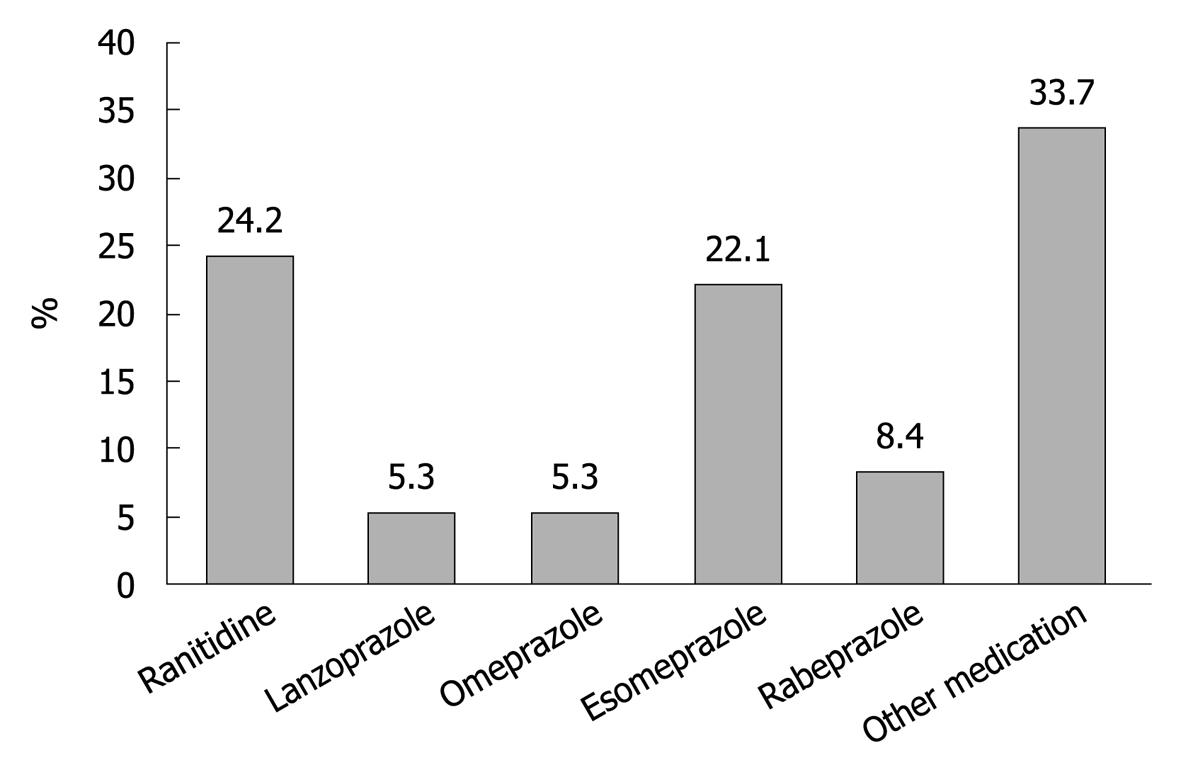

In the 2006 questionnaire individuals were asked additional questions regarding heartburn during the preceding week. Heartburn during the preceding week was reported by 20.8% of the subjects (19.0% male, 22.1% female). Of these, 60.5% reported taking medicine for heartburn. Increasing age was not a significant factor in prevalence of heartburn/reflux disease. Age was, however, a significant factor associated with the use of medication for heartburn (Figure 1). Most subjects took ranitidine or esomeprazole for their symptoms (Figure 2).

27.3% reported they were on constant medication. Most individuals (85.6%) reported taking medication only when they experienced symptoms (Table 4), although there was some overlap here between groups. Six subjects reported having had an operation for reflux disease.

| Variable | n | % of heartburn prior week |

| On constant medication | 30 | 27.3 |

| Medication only when experiencing symptoms | 77 | 85.6 |

| Tiredness (lethargy) | ||

| Frequent | 20 | 13.2 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 73 | 48.0 |

| Never | 59 | 38.8 |

| Heartburn caused by food and beverages | ||

| Very often | 32 | 20.0 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 118 | 73.8 |

| Never | 10 | 6.3 |

| Increased heartburn caused by specific food | ||

| Very often | 35 | 22.7 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 92 | 59.7 |

| Never | 27 | 17.5 |

Tiredness or lethargy was reported as occurring frequently by 13.2% of subjects, reported rarely or seldom by 48%, and reported as never having occurred by 38.8% (Table 4).

Heartburn caused by food or beverages was reported as occurring very often by 20%, 73.8% reported some or minimal heartburn and 6.3% never. Increased heartburn caused by a specific food was reported as occurring very often by 22.7% and sometimes by 59.7%. A specific food significantly more often provoked considerable heartburn in women than in men (Table 4).

As can be seen in Table 5, heartburn can affect symptoms or activities in many cases. Three out of four heartburn subjects claimed that they felt badly sometimes or seldom. One out of three heartburn subjects felt hopeless, anxious or impatient. And one out of three also reported being worried or scared because of heartburn every week.

| Variable | n | % of heartburn prior week |

| Felt bad | ||

| Frequent | 21 | 13.1 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 119 | 74.4 |

| Never | 20 | 12.5 |

| Less food and beverages consumption | ||

| Frequent | 9 | 5.9 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 77 | 50.3 |

| Never | 67 | 43.8 |

| Less family activities | ||

| Frequent | 1 | 0.6 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 32 | 20.8 |

| Never | 121 | 78.6 |

| Trouble with sleeping | ||

| Frequent | 9 | 5.8 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 70 | 45.2 |

| Never | 76 | 49.0 |

| Felt hopeless, worried or impatient | ||

| Frequent | 9 | 5.8 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 42 | 27.3 |

| Never | 103 | 66.9 |

| Felt worried or scared for their health | ||

| Frequent | 5 | 3.2 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 47 | 30.3 |

| Never | 103 | 66.5 |

| Felt irritable | ||

| Frequent | 21 | 13.6 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 80 | 51.9 |

| Never | 53 | 34.4 |

| Neglect specific food or alcohol | ||

| Frequent | 36 | 23.1 |

| Seldom | 66 | 42.3 |

| Never | 54 | 34.6 |

| Affects their daily activities | ||

| Frequent | 3 | 1.9 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 32 | 20.5 |

| Never | 121 | 77.6 |

| Unable to move (sports, hobbies and outside of home) | ||

| Frequent | 3 | 1.9 |

| Sometimes/seldom | 34 | 21.8 |

| Never | 119 | 73.6 |

Only 1.9% of the subjects reported that heartburn frequently affected their daily activities, whereas one fifth claimed that their daily activities were only sometimes or seldom affected by heartburn. Three out of four subjects reported that heartburn made them irritable. And one out of four heartburn subjects reported that heartburn resulted in less family activities, affected their daily activities and meant they were unable to move in sports, hobbies and outside of home. Half of the heartburn subjects reported trouble with sleeping because of heartburn.

Many heartburn subjects reported less food and beverage consumption and that they avoided specific food or alcohol because of the heartburn.

In this study our main focus was on the natural history of heartburn over a 10-year period in an Icelandic population. The only other long-term study, to our knowledge, that has focused on heartburn is a long-term community study in Sweden covering a maximum of 7 years[3]. There are strengths and weaknesses in both studies, but taken together they give a reasonably accurate picture of the natural history of heartburn.

The strength of our study is the use of a stable, homogeneous and well-informed population. The sample was randomly selected from the National Registry of Iceland and represented the nation as a whole in selected age groups. The population of Iceland was around 300 thousand inhabitants at the time of the study and the sample was approximately 1% of the whole population from all around the country. The BDQ, the questionnaire used, assesses the whole range of gastrointestinal functional disorders.

The prevalence of heartburn is high in Iceland. More than two out of five subjects reported heartburn in the preceding year. Half of those reported heartburn in the preceding week. Heartburn was reported as still existing after 10 years for 2 out of 3 subjects in the study. The study by Agréus et al[3] showed that the prevalence of predominant gastroesophageal reflux symptoms appears to be stable over time. Results from studies of patients suggest that GERD is a chronic disease in most cases[3,16,17]. One third of subjects who did not report heartburn in 1996 had developed heartburn 10 years later. So even though the total prevalence of heartburn was almost the same in both 1996 and 2006, there was a change among over one third of subjects reporting heartburn.

Heartburn subjects with a BMI either lower than or higher than normal weight were more likely to experience heartburn than subjects with normal weight. A study by Aro et al[18] found that reflux symptoms are linked to obesity and specifically that the presence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms was linked to reflux esophagitis in the obese population. Festi et al[19] concluded that it was likely that GERD and obesity are in some way linked and that it was possible to hypothesize that GERD may be a curable condition through the control of body weight. This may also be true for heartburn.

The transition analysis showed a substantial change in numbers in all the categories. The stability of each disease varied. FD subjects were the most stable throughout the 10 years (52.3%). Of the heartburn group 39.3% were stable, as were 30.3% of the IBS group and 15.4% of the frequent abdominal pain group. A quarter of the heartburn group had increased symptoms in 10 years, 4.6% decreased symptoms and one third developed no symptoms in 10 years. There was a significant relationship between IBS and heartburn as well as FD and heartburn.

Half (45.1%) of the subjects who reported heartburn in the preceding year experienced heartburn in the previous week. Food and beverages play a large part in eliciting heartburn; very often in 20.0% of the cases and sometimes in 73.8% of the cases. Subjects also very often experienced increased heartburn caused by a specific food in 22.7% of the cases. Heartburn did not seem to be the cause for less food and beverage consumption, but one out of five heartburn subjects did avoid a specific food or alcohol because of heartburn. Festi et al[19] report that no definitive data exist regarding the role of diet and specific foods or drinks in GERD clinical manifestations[19].

Heartburn is associated with feeling tired (61.2%), feeling bad (87.5%) and with irritation (65.5%). One third felt worried or scared for their health because of heartburn symptoms and one third also felt that heartburn caused them to feel hopeless, worried or impatient (33.1%). Every fifth heartburn subject reported that heartburn affected activities such as daily and family activities, as well as that heartburn caused them to be unable to move normally and therefore affected their participation in sports, hobbies and outdoor activities. This effect of heartburn on normal life and activities may have affected the subjects in the manner of a chronic condition throughout the 10 years of the study, and therefore had a great impact on quality of life. This finding is in line with McDougall et al[17] who showed in their study on reflux esophagitis and quality of life that it was not bodily pain and vitality that were impaired, but general health and social function.

Three out of five of all the heartburn subjects in 2006 reported taking medicine for heartburn. Almost all the subjects who were on medication for heartburn reported relief provided by the medication. Age was a significant factor for the use of medication for heartburn. Most subjects took ranitidine or esomeprazole for their symptoms.

Few studies have addressed the impact of nocturnal reflux symptoms in heartburn subjects. A study by Farup et al[20] showed that the prevalence of nighttime heartburn in GERD patients under routine care was high, up to 49% for 1 of 3 years. A population-based survey in the United States claimed that the overall prevalence of nocturnal GERD symptoms was 10%, with 74% of subjects with GERD symptoms fitting the criteria for nocturnal GERD[21]. In our study, sleep was frequently affected in 5.8% of cases and 45.2% of heartburn subjects were sometimes or seldom troubled with sleeping in the prior week. These numbers can be expected to be higher for the preceding year, since we asked specifically about the preceding week.

There are some limitations to our study. The subjects were not specifically interviewed or examined to evaluate the possibility of organic disease. However, a 10-year (postal) follow-up went some way towards making an organic cause of symptoms unlikely. Furthermore, since the response rate was 66.8% in 1996 and 67.7% in 2006, a dropout bias cannot be excluded.

In summary, heartburn is a common condition in the population of Iceland. The prevalence is slightly higher than reported elsewhere. Heartburn is a chronic condition, affecting every fifth person every week. Heartburn subjects with a BMI lower or higher than normal weight were more likely to experience heartburn than subjects of normal weight. Heartburn did not seem to result in less food and beverage consumption, but one out of five heartburn subjects did avoid a specific food or alcohol because of the heartburn. Heartburn had a great impact on daily activities and quality of life. Half of the heartburn subjects experienced sleep disturbances because of this condition.

Heartburn is a signature symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which is a cluster of symptoms and signs associated with regurgitation of stomach acid up to the pharynx and mouth. Patient-based studies of GERD have shown high prevalence and chronicity, particularly in Western societies. GERD is associated with significant health-care utilization and diminished quality of life. Heartburn, coupled with acid regurgitation and painful swallowing are considered to be highly specific for GERD. Very few epidemiological studies have been performed with regard to heartburn, and only one has been population-based. The natural history of GERD or heartburn has received little attention. The pathophysiology of GERD and heartburn is basically unknown.

The prevalence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population is high and symptoms are associated with significant socioeconomic consequences. The prevalence and natural history of heartburn is of importance as well as its association with functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome, and sociodemographic factors such as body mass index (BMI). The aim of the present study was therefore to evaluate the natural history of heartburn in the Icelandic population prospectively over a 10-year period, as well as to evaluate different factors which are associated with heartburn both physically and sociodemographically.

The prevalence of heartburn is high in Iceland. More than two out of five subjects reported heartburn in the preceding year. Half of those reported heartburn in the preceding week. Heartburn was reported as still existing after 10 years for 2 out of 3 subjects in the study. Heartburn subjects with a BMI either lower or higher than normal weight were more likely to experience heartburn than subjects with normal weight. There was an association between heartburn, functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome and patients floated over time between these categories. This suggests a common etiopathogenesis of these disorders. The quality of life was diminished due to a variety of factors such as worries, irritability, intolerance to specific foods and sleep disturbance.

The prevalence and natural history of heartburn and its risk factors are important for management and prognosis. Heartburn can be regarded as a reliable surrogate marker of GERD. This study creates a database for future studies and hopefully stimulates studies in other countries. Secular prevalence trends and international comparison can contribute towards understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease.

A 10-year follow-up population-based, questionnaire study of the Icelandic population was performed. The primary aim was to study the prevalence and natural history of heartburn. Subjects were classified as having heartburn if they reported heartburn according to the following definition: Heartburn is a burning sensation in the retrosternal area (behind the breastbone). The pain often rises in the upper abdomen and may radiate to the chest.

Heartburn alone has a prevalence of 17%-42% in Western populations and is associated with extensive health care expenses and diminished quality of life. Comparative international population-based studies are needed to document secular trends and to elucidate the reasons for the different prevalence in various countries.

Peer reviewer: Joachim Labenz, Associate Professor, Jung-Stilling Hospital, Wichernstr. 40, Siegen 57074, Germany

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Armstrong D, Mönnikes H, Bardhan KD, Stanghellini V. The construction of a new evaluative GERD questionnaire - methods and state of the art. Digestion. 2004;70:71-78. |

| 2. | Kulig M, Nocon M, Vieth M, Leodolter A, Jaspersen D, Labenz J, Meyer-Sabellek W, Stolte M, Lind T, Malfertheiner P. Risk factors of gastroesophageal reflux disease: methodology and first epidemiological results of the ProGERD study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:580-589. |

| 3. | Agréus L, Svärdsudd K, Talley NJ, Jones MP, Tibblin G. Natural history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional abdominal disorders: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2905-2914. |

| 4. | Lee KJ, Kwon HC, Cheong JY, Cho SW. Demographic, clinical, and psychological characteristics of the heartburn groups classified using the Rome III criteria and factors associated with the responsiveness to proton pump inhibitors in the gastroesophageal reflux disease group. Digestion. 2009;79:131-136. |

| 5. | Drossman DA. Rome III: The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3 ed. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates Inc 2006; 374-381. |

| 6. | Frank L, Kleinman L, Ganoczy D, McQuaid K, Sloan S, Eggleston A, Tougas G, Farup C. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms in North America: prevalence and relationship to healthcare utilization and quality of life. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:809-818. |

| 7. | Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710-717. |

| 8. | Olafsdottir LB, Gudjonsson H, Jonsdottir HH, Thjodleifsson B. Natural history of functional dyspepsia: a 10-year population-based study. Digestion. 2010;81:53-61. |

| 9. | Olafsdottir LB, Gudjonsson H, Jonsdottir HH, Thjodleifsson B. Stability of the irritable bowel syndrome and subgroups as measured by three diagnostic criteria - a 10-year follow-up study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:670-680. |

| 10. | Olafsdóttir LB, Gudjónsson H, Thjódleifsson B. [Epidemiological study of functional bowel disorders in Iceland]. Laeknabladid. 2005;91:329-333. |

| 11. | Dillman DA. Mail and Telephon Surveys. The total design method. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons 1978; . |

| 12. | Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Assessment of functional gastrointestinal disease: the bowel disease questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:1456-1479. |

| 13. | Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Melton J 3rd, Wiltgen C, Zinsmeister AR. A patient questionnaire to identify bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:671-674. |

| 14. | Halder SL, Locke GR 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd, Talley NJ. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:799-807. |

| 15. | Attanasio V, Andrasik F, Blanchard EB, Arena JG. Psychometric properties of the SUNYA revision of the Psychosomatic Symptom Checklist. J Behav Med. 1984;7:247-257. |

| 16. | Kuster E, Ros E, Toledo-Pimentel V, Pujol A, Bordas JM, Grande L, Pera C. Predictive factors of the long term outcome in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: six year follow up of 107 patients. Gut. 1994;35:8-14. |

| 17. | McDougall NI, Johnston BT, Kee F, Collins JS, McFarland RJ, Love AH. Natural history of reflux oesophagitis: a 10 year follow up of its effect on patient symptomatology and quality of life. Gut. 1996;38:481-486. |

| 18. | Aro P, Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Storskrubb T, Bolling-Sternevald E, Agréus L. Body mass index and chronic unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms: an adult endoscopic population based study. Gut. 2005;54:1377-1383. |

| 19. | Festi D, Scaioli E, Baldi F, Vestito A, Pasqui F, Di Biase AR, Colecchia A. Body weight, lifestyle, dietary habits and gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1690-1701. |

| 20. | Nocon M, Labenz J, Jaspersen D, Leodolter A, Meyer-Sabellek W, Stolte M, Vieth M, Lind T, Malfertheiner P, Willich SN. Nighttime heartburn in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease under routine care. Digestion. 2008;77:69-72. |

| 21. | Farup C, Kleinman L, Sloan S, Ganoczy D, Chee E, Lee C, Revicki D. The impact of nocturnal symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:45-52. |