Published online Dec 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i47.5191

Revised: November 11, 2010

Accepted: November 18, 2010

Published online: December 21, 2011

AIM: To evaluate the effect of posterior lingual lidocaine swab on patient tolerance to esophagogastroduodenoscopy, the ease of performance of the procedure, and to determine if such use will reduce the need for intravenous sedation.

METHODS: Eighty patients undergoing diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy in a tertiary care medical center were randomized to either lidocaine swab or spray. Intravenous meperidine and midazolam were given as needed during the procedure.

RESULTS: Patients in the lidocaine swab group (SWG) tolerated the procedure better than those in the spray group (SPG) with a median tolerability score of 2 (1, 4) compared to 4 (2, 5) (P < 0.01). The endoscopists encountered less difficulty performing the procedures in the SWG with lower median difficulty scores of 1 (1, 5) compared to 4 (1, 5) in the SPG (P < 0.01). In addition, the need for intravenous sedation was also lower in the SWG compared to the SPG with fewer patients requiring intravenous sedation (13/40 patients vs 38/40 patients, respectively, P < 0.01). The patients in the SWG were more satisfied with the mode of local anesthesia they received as compared to the SPG. In addition, the endoscopists were happier with the use of lidocaine swab.

CONCLUSION: The use of a posterior lingual lidocaine swab in esophagogastroduodenoscopy improves patient comfort and tolerance and endoscopist satisfaction and decreases the need for intravenous sedation.

- Citation: Soweid AM, Yaghi SR, Jamali FR, Kobeissy AA, Mallat ME, Hussein R, Ayoub CM. Posterior lingual lidocaine: A novel method to improve tolerance in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(47): 5191-5196

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i47/5191.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i47.5191

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is an essential and very commonly used procedure for the evaluation of a multitude of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms including abdominal pain, hemorrhage, dysphagia, odynophagia, and reflux[1-3]. Although EGD is fairly safe, it carries a low risk of complications including perforation, bleeding, infection, and medication reactions/adverse effects[2,4,5]. Several studies showed that patients with advanced age and those with cardiopulmonary disease may carry an increased risk for the procedure especially when high doses of intravenous (IV) sedatives are used[2,6,7]. Various IV agents such as midazolam, meperidine, propofol, and fentanyl have been used over the past few decades for their anxiolytic, amnestic, and analgesic effects during the procedure[8-10]. However, these agents carry potential serious adverse effects especially in high risk patients. These complications include apnea, hypoxia, vomiting, hypotension, agitation, and allergic reactions[11-16]. In addition, complications of IV sedation contributed to cost increase due to unexpected hospitalizations and work related absenteeism on the procedure day. This has led to search for modes of anesthesia that carry less complication rates and, at the same time, provide satisfaction for both patient and endoscopist[12,15,17-24]. Few studies have used different forms of topical anesthesia including, spray, lollipop, and inhaler with mixed results. Some of these topical agents still carried a risk of retching, vomiting, and apnea[8,19,20,23,25-28]. Conventionally, topical lidocaine spray is used combined with IV analgesics and sedatives before and during the procedure to achieve a high level of patient comfort and endoscopist satisfaction[4,19,26,27,29].

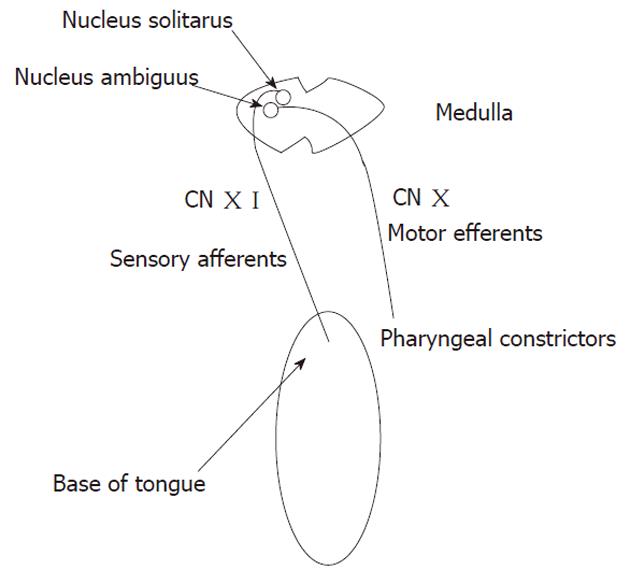

The rationale behind the use of topical anesthesia is to suppress the gag reflex that may account for some of the EGD-related discomfort. The gag reflex is one of the normal reflexes induced by stimulation of the pharynx and velar area. It involves the contraction of pharyngeal constrictors induced by touching one of the five trigger zones that include: base of tongue, uvula, palate, posterior pharyngeal wall, and palatopharyngeal and palatoglossal folds[30]. The gag reflex consists of an afferent and an efferent arches. The afferent receives input from nerve fibers of the glossopharyngeal nerve which are relayed in the nucleus solitaris. The efferent arch is supplied by the nucleus ambiguus through the vagus nerve (Figure 1)[31]. These nuclei are at close proximity to the vomiting and salivating centers, which explains the experience of retching and excessive salivation when the gag reflex is elicited[30]. Both superficial and deep sensory receptors are involved in the physiology of the gag reflex, and this makes a pharyngeal plexus block superior to topical lidocaine spray in suppressing the reflex[32]. When a person eats, central voluntary action on the pharyngeal muscles dominates over the gag reflex and this is why there is no gagging when eating[30]. Therefore, if lidocaine is to be applied specifically to the above-mentioned five trigger areas in the pharynx, then the gag reflex would be markedly attenuated or even ablated during the procedure, which may further increase the patients’ tolerance to EGD and in turn decrease IV sedation use. The use of lidocaine in the gel form may be ideal since a dense/sticky form of lidocaine may provide a more reliable local anesthesia compared to the spray.

In this study, the efficacy of posterior lingual lidocaine as a potential anesthetic technique in patients undergoing EGD was compared to that of the conventional lidocaine spray. Our main objective is to evaluate the effect of posterior lingual lidocaine application on patient tolerance to the procedure and the ease of performance of the procedure. Our secondary aim is to determine if such use will reduce the need for IV sedation.

Our target population was patients undergoing diagnostic EGD for various indications at the American University of Beirut-Medical Center (AUB-MC). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board committee at AUB-MC in accordance with Helsinki Declaration. The details regarding the study objectives and risks were fully explained to the patients and those who agreed to participate in the study were recruited and signed the informed consent.

After signing the informed consent, patients were randomly assigned to one of two study groups: the swab group (SWG) who received 150 mg of lidocaine gel or the spray group (SPG) who received 300 mg lidocaine spray. Lidocaine spray was administered using the same technique in 3 consecutive 30-s intervals, each consisting of 10 sprays (10 mg/dose) of Xylocaine® Pump Spray 10% (AstraZeneca AB, Sodertalje, Sweden). In the swab group, Xylocaine® Jelly 2% (AstraZeneca AB, Sodertalje, Sweden), with a lidocaine concentration of 20 mg/mL was used. A total of 7.5 mL (150 mg) of lidocaine gel was gradually applied to the base of the tongue and the peritonsillar areas. The endoscopist was totally blinded to the randomization. The endoscope used in the procedures was GIF-1T 240 (Olympus Optical, 11 mm diameter, Tokyo, Japan). All the patients had IV lines inserted and their vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate) and pulse oxymetry were continuously monitored during the procedure. The data that was collected by the research fellow from all enrolled patients before the procedure included the following parameters: age, gender, past medical history, past surgical history, medications, allergies, alcohol use, smoking, illicit drug use, and history of previous endoscopy (including tolerance to it). None of the participants had any severe pulmonary disease (asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). The research fellow then determined the patients’ anxiety level according to a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = no anxiety to 5 = extreme anxiety). After the topical anesthetics were applied, the time for the onset of the topical anesthesia was also noted (from the time the local anesthetic was applied till patients reported numbness in the oral cavity and the inability to swallow).

In both study groups, the decision to administer IV sedation during the procedure was made by the endoscopist depending on the patient’s tolerance and the presence or absence of signs of discomfort, like excessive gag, retching, or restlessness. Sedatives used were midazolam and meperidine. The duration of the procedure was also noted.

After the administration of the local anesthetics, the endoscopist rated the gag reflex based on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = absent to 5 = strong). After the procedure, the endoscopist determined the ease of the procedure based on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = easy to 5 = difficult). Finally, the amount of IV sedation given was recorded.

After the procedure was concluded, patients were monitored in the recovery room. Afterwards, a questionnaire was filled in by the participants to determine tolerance to the procedure based on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = no difficulties encountered to 5 = very difficult). Also, symptoms during (retching, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dyspnea, cough) and after (sore throat, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dyspnea, cough) the procedure were recorded. Patients were also asked to specify the most uncomfortable phase of the procedure and their willingness to repeat the procedure using the same local anesthetic.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). The nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used to compare ordinal variables (such as the gag reflex, procedure evaluation, etc.) and data that are not normally distributed (the doses of meperidine and midazolam) between SWG and SPG groups.

The χ2 test was utilized to compare categorical variables between the 2 groups. Continuous variables were assessed with an independent sample t test. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Our study included 80 consecutive patients who underwent an elective EGD at AUB-MC. There were 31 males (38.8%) and 49 females (61.2%) with a mean age of 52.2 ± 18.4 years. There was no statistically significant difference in the patients’ characteristics in both groups (Table 1).

| SWG (n = 40) | SPG (n = 40) | P value | |

| Gender (M/F) | 12/28 | 19/21 | 0.11 |

| Mean age, yr (SD) | 55.8 (18.1) | 48.5 (18.2) | 0.07 |

| Smoking (yes/no) | 15/25 | 23/17 | 0.07 |

| Caffeine (yes/no) | 37/3 | 32/8 | 0.19 |

| Alcohol (yes/no) | 12/28 | 14/26 | 0.63 |

| Previous EGD (yes/no) | 17/23 | 23/17 | 0.18 |

Anxiety before the procedure was rated on an ascending scale from 1 to 5 as detailed in the method section. There was no significant difference between the two groups; the median anxiety scores were 3 (1, 5) for subjects in SWG and SPG.

The time interval between the lidocaine administration and the onset of anesthesia was significantly longer in the SWG as compared to the SPG, with median time 80 (30, 300) and 50 (20, 120) s (P < 0.01, respectively).

The SPG had significantly stronger gag reflex than the SWG with respective median scores of 4 (1, 5) and 2 (1, 5) (P < 0.01, Table 2).

IV sedation was administered more frequently in the SPG than the SWG (95% vs 32%, P < 0.01).

The amount of meperidine administered was significantly lower in the SWG compared to the SPG, with median doses of 0 (0, 50) and 25 (0, 75) mg, respectively, P < 0.01. Similarly, the dose of midazolam was significantly lower in the SWG as compared to the SPG with median doses of 0 (0, 3) and 2 (0, 4) mg (P < 0.01, respectively, Table 3).

The endoscopist’s assessment of the degree of procedure difficulty showed that the procedures were significantly easier to perform in the SWG than the SPG, with median difficulty scores of 1 (1, 5) and 4 (1, 5) (P < 0.01, respectively, Table 4).

Additionally, the procedure was significantly much easier to perform in subjects who did not receive IV sedation compared to those who received either meperidine or midazolam, with median difficulty scores of 1 (1, 3) and 4 (1, 5) (P < 0.01), respectively.

Patients in the SWG tolerated the procedure more with a median tolerability score of 2 (1, 4) as compared to 4 (2, 5) in the SPG (P < 0.01, Table 4).

The most difficult part of the procedure was the introduction of the endoscope as reported by 68.8 % of patients. Thirty two (80%) subjects in the SWG expressed their willingness to repeat the procedure under the same local anesthesia, versus only 2 (5%) patients in the SPG (P < 0.01, Table 4).

The side effects during and after the procedure were similar in both groups except for retching which was significantly lower in the SWG than in the SPG (13/40 vs 31/40 patients, respectively, P < 0.01, Table 5).

| SWG (n = 40) | SPG (n = 40) | P value | |

| During the procedure | |||

| Retching (yes/no) | 13/27 | 31/9 | < 0.01 |

| Cough (yes/no) | 10/30 | 12/28 | 0.62 |

| Abdominal pain (yes/no) | 1/39 | 1/39 | 1 |

| Dyspnea (yes/no) | 0/40 | 4/36 | 0.12 |

| After the procedure | |||

| Sore throat (yes/no) | 5/35 | 8/32 | 0.55 |

| Abdominal pain (yes/no) | 1/39 | 5/35 | 0.2 |

| Nausea/vomiting (yes/no) | 0/40 | 1/39 | 1 |

None of the procedures was aborted due to complications, excessive agitation or major patient discomfort.

The use of conscious sedation along with lidocaine spray is the standard of care in upper GI endoscopy[4,19,26,27,29]. However, IV sedation may cause potential harm to the patients especially the elderly with co-morbidities. These side effects include hypotension, respiratory depression, and paradoxical agitation[7,11-16]. The potential risks of upper GI endoscopy are mostly related to the use of IV sedation[1,2,11,16,27,33-35]. Studies done by Campo et al[6] and Mulcahy et al[7] showed that a high level of anxiety, young age, and a strong gag reflex are risk factors for poor tolerance to upper GI endoscopy. On the other hand, a study done by Pereira et al[27] showed that patients’ anxiety did not contribute to procedure tolerance. Local oropharyngeal anesthesia including lidocaine has been studied in several trials with the results showing that the use of the lidocaine spray or gel with IV sedation increased the tolerability and ease of the procedure and reduced the risk of discomfort during the procedure[23,26,28,29,36]. A single study, however, was done on the lidocaine lollipop which showed excellent efficacy in achieving patient comfort even without the use of IV sedation[28]. The action of local oropharyngeal anesthesia is achieved mainly by inhibiting the gag reflex which is one of the most important factors affecting the tolerability and ease of the procedure[6,28]. So in order to perform the procedure without possibly using IV sedation, an effective local agent that suppresses the gag reflex should be used.

Our study showed that when lidocaine gel is applied to the posterior lingual area, it effectively suppresses the gag reflex, significantly increases the patient tolerability to the procedure, improves endoscopist satisfaction of the procedure, and considerably decreases the need for IV sedation. The level of anxiety and age were similar in both groups; thus, these factors can be eliminated as confounding variables. Therefore, lidocaine gel could be used as a sole agent in upper GI endoscopy sparing the use of IV sedation with its potential complications. In addition, this may help patients resume their daily activities immediately after the procedure. Although we did not compare the cost of the lidocaine gel and spray, the use of the gel appears to be more cost-effective since potential adverse events related to IV sedation are reduced. The maximal dose of lidocaine used in the spray group was 300 mg. This dose of lidocaine is within the recommended dose of 5 mg/kg and does not exceed the potentially toxic dose of 500 mg[37]. Moreover, higher doses of topical lidocaine had been used in prior studies. Sutherland et al[38], for instance, utilized topical doses of 380 mg of lidocaine and concluded that the blood levels were still within therapeutic range. The dose of lidocaine used in the gel group was much lower (150 mg) than that in the spray group. Despite that decrease in the dose, there was more effective suppression of the gag reflex in the gel group, and hence, better tolerance to the EGD.

Sample size was one of the few limitations in this study. Because it was a small sample, subgroup analysis could not be performed. Another limitation that might have affected our results can be attributed to the impairment in judgmental abilities caused by the sedatives used in some cases.

In conclusion, this study presented evidence that the use of lidocaine swab applied to the posterior lingual area was an effective mode of local anesthesia in upper GI endoscopy. This can lead to reduction in the use of IV sedatives (and potentially their complications) and may decrease the overall cost of the procedure. This may be a very promising modality especially in the elderly patients who have comorbidities, and in office-based upper GI endoscopy. However, larger, multicenter studies should be done to confirm and validate the results of our study.

The data of this study has been presented as a poster at the Digestive Disease Week in New Orleans, 2010.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) has become an essential and very commonly used procedure for the diagnostic and therapeutic evaluation of a multitude of upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and diseases. EGD is considered a safe procedure with a very low risk of complications. Medication administered for local anesthesia and for conscious sedation during the procedure can pose some adverse effects especially in the elderly population. So finding ways to decrease the need for these drugs would decrease the complication rates. The rationale behind the use of topical anesthesia is to decrease the gag reflex that may account for a major part of EGD-related discomfort. Using lidocaine as a topical anesthetic in the gel form may be ideal since a dense/sticky form of lidocaine may provide a more reliable local anesthesia compared to the spray thus increasing the patients’ tolerance to EGD and in turn decreasing the need for intravenous (IV) sedation.

Improving the tolerance and ease of execution of EGD procedures has gained much interest recently. The primary objective of this clinical research approach is to decrease the need for drugs used for conscious sedation to spare patients the side effects and the costs of elevated doses of such agents. Research is currently focusing on increasing the effectiveness of drug administration, improving patients’ tolerance, and using/developing ultrathin endoscopes.

This study showed that when lidocaine gel is applied to the posterior lingual area, it effectively suppresses the gag reflex, significantly increases the patient tolerability to the procedure, improves endoscopist satisfaction of the procedure, and considerably decreases the need for IV sedation.

The authors presented evidence that the use of lidocaine swab applied to the posterior lingual area was an effective mode of local anesthesia in upper GI endoscopy. This can lead to reduction in the use of IV sedatives (and potentially their complications) and may decrease the overall cost of the procedure. This may be a very promising modality especially in the elderly patients with co-morbidities, and in office-based upper GI endoscopy.

Conscious sedation: Defined as moderate sedation by the American Society of Anesthesiologists. It is the reduction of irritability or agitation by administration of sedative drugs such as midazolam with purposeful preservation of the response to verbal or tactile stimulation. Posterior lingual lidocaine swab: A technique whereby local anesthesia is achieved by the application of lidocaine gel to the base of the tongue and the peritonsillar areas as opposed to application via the aerosolized spray form routinely utilized.

This article showed that the effectiveness of the posterior lingual lidocaine swab is statistically significant. The study design and analysis ensures the validity of achieved results and nearly eliminated causes of random error. Nonetheless, increasing the patients’ number and possibly involving other centers in this study would undeniably increase its power and reliability.

Peer reviewer: Hoon Jai Chun, MD, PhD, AGAF, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Institute of Digestive Disease and Nutrition, Korea University College of Medicine, 126-1, Anam-dong 5-ga, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 136-705, South Korea

S- Editor Yang XC L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Clarke GA, Jacobson BC, Hammett RJ, Carr-Locke DL. The indications, utilization and safety of gastrointestinal endoscopy in an extremely elderly patient cohort. Endoscopy. 2001;33:580-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Van Kouwen MC, Drenth JP, Verhoeven HM, Bos LP, Engels LG. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients aged 85 years or more. Results of a feasibility study in a district general hospital. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;37:45-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Seinelä L, Reinikainen P, Ahvenainen J. Effect of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy on cardiopulmonary changes in very old patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;37:25-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ross R, Newton JL. Heart Rate and Blood Pressure Changes during Gastroscopy in Healthy Older Subjects. Gerontology. 2004;50:182-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Campo R, Brullet E, Montserrat A, Calvet X, Moix J, Rué M, Roqué M, Donoso L, Bordas JM. Identification of factors that influence tolerance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:201-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mulcahy HE, Kelly P, Banks MR, Connor P, Patchet SE, Farthing MJ, Fairclough PD, Kumar PJ. Factors associated with tolerance to, and discomfort with, unsedated diagnostic gastroscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1352-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Keeffe EB, O'Connor KW. 1989 A/S/G/E survey of endoscopic sedation and monitoring practices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:S13-S18. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Tu RH, Grewall P, Leung JW, Suryaprasad AG, Sheykhzadeh PI, Doan C, Garcia JC, Zhang N, Prindiville T, Mann S. Diphenhydramine as an adjunct to sedation for colonoscopy: a double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:87-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Waring JP, Baron TH, Hirota WK, Goldstein JL, Jacobson BC, Leighton JA, Mallery JS, Faigel DO. Guidelines for conscious sedation and monitoring during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:317-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Brussaard CC, Vandewoude MF. A prospective analysis of elective upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in the elderly. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:118-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chillemi S, Milici M, De Francesco F, Buda CA, Maisano C, Minutoli N, Querci A, Lemma F. [Sedation in endoscopic diagnosis: rationale of the use of specific benzodiazepine antagonists]. G Chir. 1996;17:349-352. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Külling D, Rothenbühler R, Inauen W. Safety of nonanesthetist sedation with propofol for outpatient colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:679-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ristikankare M, Julkunen R, Mattila M, Laitinen T, Wang SX, Heikkinen M, Janatuinen E, Hartikainen J. Conscious sedation and cardiorespiratory safety during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:48-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tang WL, Liu SJ, Jiang XW. [Associated sedation of propofol and midazolam in small dosage and gastroscopy]. Hunan Yike Daxue Xuebao. 2001;26:463-465. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Van Dam J, Brugge WR. Endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1738-1748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bell GD. Premedication, preparation, and surveillance. Endoscopy. 2002;34:2-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Clarke AC, Chiragakis L, Hillman LC, Kaye GL. Sedation for endoscopy: the safe use of propofol by general practitioner sedationists. Med J Aust. 2002;176:158-161. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Davis DE, Jones MP, Kubik CM. Topical pharyngeal anesthesia does not improve upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in conscious sedated patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1853-1856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dhir V, Mohandas KM. Topical pharyngeal anesthesia for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:829-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dhir V, Swaroop VS, Vazifdar KF, Wagle SD. Topical pharyngeal anesthesia without intravenous sedation during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1997;16:10-11. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Ljubicić N, Supanc V, Roić G, Sharma M. Efficacy and safety of propofol sedation during urgent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy--a prospective study. Coll Antropol. 2003;27:189-195. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Mulcahy HE, Greaves RR, Ballinger A, Patchett SE, Riches A, Fairclough PD, Farthing MJ. A double-blind randomized trial of low-dose versus high-dose topical anaesthesia in unsedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:975-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Stolz D, Chhajed PN, Leuppi J, Pflimlin E, Tamm M. Nebulized lidocaine for flexible bronchoscopy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Chest. 2005;128:1756-1760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fisher NC, Bailey S, Gibson JA. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of sedation vs. no sedation in outpatient diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 1998;30:21-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Leitch DG, Wicks J, el Beshir OA, Ali SA, Chaudhury BK. Topical anesthesia with 50 mg of lidocaine spray facilitates upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:384-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pereira S, Hussaini SH, Hanson PJ, Wilkinson ML, Sladen GE. Endoscopy: throat spray or sedation? J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1994;28:411-414. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Ayoub C, Skoury A, Abdul-Baki H, Nasr V, Soweid A. Lidocaine lollipop as single-agent anesthesia in upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:786-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Soma Y, Saito H, Kishibe T, Takahashi T, Tanaka H, Munakata A. Evaluation of topical pharyngeal anesthesia for upper endoscopy including factors associated with patient tolerance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:14-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bassi GS, Humphris GM, Longman LP. The etiology and management of gagging: a review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent. 2004;91:459-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Miller AJ. Oral and pharyngeal reflexes in the mammalian nervous system: their diverse range in complexity and the pivotal role of the tongue. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:409-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Valley MA, Kalloo AN, Curry CS. Peroral pharyngeal block for placement of esophageal endoprostheses. Reg Anesth. 1992;17:102-106. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Dean R, Dua K, Massey B, Berger W, Hogan WJ, Shaker R. A comparative study of unsedated transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy and conventional EGD. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:422-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Carey EJ, Sorbi D. Unsedated endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2004;14:369-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Trevisani L, Sartori S, Gaudenzi P, Gilli G, Matarese G, Gullini S, Abbasciano V. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: are preparatory interventions or conscious sedation effective? A randomized trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3313-3317. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Campo R, Brullet E, Montserrat A, Calvet X, Rivero E, Brotons C. Topical pharyngeal anesthesia improves tolerance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a randomized double-blind study. Endoscopy. 1995;27:659-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Antoniades N, Worsnop C. Topical lidocaine through the bronchoscope reduces cough rate during bronchoscopy. Respirology. 2009;14:873-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sutherland AD, Santamaria JD, Nana A. Patient comfort and plasma lignocaine concentrations during fibreoptic bronchoscopy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1985;13:370-374. [PubMed] |