Published online Nov 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i43.4835

Revised: June 21, 2011

Accepted: June 29, 2011

Published online: November 21, 2011

Lipomatous hemangiopericytomas (LHPCs) are rare soft-tissue tumors that are histologically characterized by hemangiopericytomatous vasculature and the presence of mature adipocytes. We present the clinicopathological features of a case of gastric LHPC in a 56-year-old female, along with a literature review. Endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound showed a submucosal tumor 0.8 cm across in the greatest dimension in the lesser curvature side of the gastric antrum. Grossly, the well-defined mass had a solid and tan-white cut surface admixed with myxoid regions and yellowish areas. Histological examination revealed a submucosal well-circumscribed lesion composed of cellular nodules with the classic appearance of an hemangiopericytoma admixed with clusters and lobules of mature adipocytes. The ill-defined tumor cells had weakly eosinophilic cytoplasm and contained spindled nuclei with occasional small nucleoli. Nuclei atypia and mitoses were absent, and no cellular atypia, necrosis or vascular invasion was observed. Immunohistochemistry showed that the tumor cells were diffusely positive for CD34, CD99, and vimentin and were focally reactive for bcl-2. This is the first known report of an LHPC in the stomach. The patient was followed for 12 mo without any evidence of metastasis or recurrence.

- Citation: Jing HB, Meng QD, Tai YH. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma of the stomach: A case report and a review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(43): 4835-4838

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i43/4835.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i43.4835

Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma (LHPC) is a recently recognized rare hemangiopericytoma (HPC) variant that is histologically composed of an admixture of benign hemangiopericytomatous and mature lipomatous components[1]. To date, 49 cases of LHPC have been documented in published English language reports (Table 1)[1-19], but tumors developing in visceral organs such as the stomach have not been reported. Herein, we report the clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of what is, to our knowledge, the first case of an LHPC occurring in the stomach and present a review of the literature.

| Ref. | Sex/age(yr) | Location | Size (cm) | Follow-up (mo) |

| Liu et al[19] | M/61 | Mediastinum | 9.5 | NED/28 |

| Aftab et al[18] | M/38 | Spine | NA | NED/6 |

| Dozois et al[17] | M/21 | Pelvic cavity | 18 | NA |

| Kim et al[16] | M/43 | Perineum | 5.5 | NA |

| Pitchamuthu et al[15] | F/49 | Orbit | 3.5 | NA |

| Yamazaki et al[14] | M/54 | Lung | 4 | NA |

| Farah-Klibi et al[13] (Abstract) | NA | Orbit | NA | NA |

| Shaia et al[12] | F/36 | Skull base | 5.5 | NED/12 |

| Amonkar et al[11] | M/39 | Mediastinum | 6.5 | NED/12 |

| Verfaillie et al[10] | F/79 | Axilla | 9 | NA |

| Yamaguchi et al[9] | F/51 | Kidney | 10 | NA |

| Alrawi et al[8] | F/55 | Occipital area and upper neck | 9 | NED/12 |

| Domanski[7] | F/51 | Thigh | 5 | NED/24 |

| M/56 | Abdominal wall | 3 | NED/12 | |

| Cameselle-Teijeiro et al[6] | M/36 | Thyroid | 6 | NED/25 |

| Davies et al[5] | M/65 | Orbit | 3.5 | NED/48 |

| Guillou et al[4] | M/54 | Retroperitoneum | 7.5 | NED/72 |

| F/42 | Mediastinum | 2.5 | NED/36 | |

| F/68 | Hip | 1.7 | NA | |

| M/33 | Hip | 4.5 | NED/14 | |

| M/48 | Elbow | 5 | NA | |

| F/39 | Thigh | 10 | NED/22 | |

| F/27 | Neck | 5.5 | NED/12 | |

| F/43 | Right iliac fossa | 5.5 | Recent case | |

| F/75 | Epicardium | 4.5 | NED/60 | |

| F/67 | Poplitea fossa | 9 | NED/6 | |

| M/46 | Retroperitoneum | 19 | NED/6, then lost to follow-up | |

| M/53 | Orbit | 2 | NED/77 | |

| M/51 | Retroperitoneum | 18 | NED/6 | |

| Folpe et al[3] | M/51 | Calf | 3 | NED/36 |

| M/74 | Pelvic cavity | 9 | NA | |

| M/53 | Retroperitoneum | NA | NED/84 | |

| M/33 | Retroperitoneum | 18 | NA | |

| M/72 | Supraclavicular | NA | NED/60 | |

| M/61 | Pelvic cavity | 12 | NA | |

| F/49 | Submandibular | 5 | NED/60 | |

| M/33 | Thigh | 6 | NA | |

| F/49 | Thigh | 13 | NA | |

| M/60 | Thigh | 21 | NED/48 | |

| F/39 | Calf | 4 | NED/36 | |

| M/60 | Para-spinous, T7-10 | NA | NA | |

| M/51 | Thigh | 17 | NED/24 | |

| M/64 | Chest wall | 6 | Recent case | |

| M/63 | Inguinal | NA | Recent case | |

| F/74 | Hip | 8 | Recent case | |

| Ceballos et al[2] | F/41 | Thigh | 9 | NED/13 |

| Nielsen et al[1] | F/44 | Sinonasal area | 7 | NED/48 |

| M/56 | Shoulder | 4 | NED/4 | |

| M/72 | Retroperitoneum | 10 | Recent case | |

| Present case | F/56 | Stomach | 0.8 | NED/12 |

A 56-year-old female presented with slight left epigastric pain that had been present for two months. Her past medical history and family history were unremarkable. The laboratory data were within normal limits. Endoscopy showed a submucosal tumor of 0.8 cm in the greatest dimension in the lesser curvature side of the gastric antrum. The broad-base mass with a smooth external surface protruded into the lumen. The overlying mucosa was normal in texture and color. On endoscopic ultrasound, an oval, well-defined, hyperechoic mass was detected lying beneath the mucosa but protruding into the lumen. Given the clinical suspicion of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), endoscopic resection was performed with a diathermy snare after ligation with a detachable snare. The neoplasm was completely excised. Her postoperative course was uneventful. She was well, without evidence of recurrence or metastasis, 12 mo after resection.

On gross pathology, the specimen consisted of a nodular mass measuring 0.8 cm × 0.6 cm × 0.5 cm with an attached portion of gastric mucosa. Sectioning revealed a well-demarcated, nonencapsulated mass with a solid and tan-white appearance admixed with myxoid regions and yellowish areas. The tumor was soft and rubbery in consistency without involving the overlying mucosa.

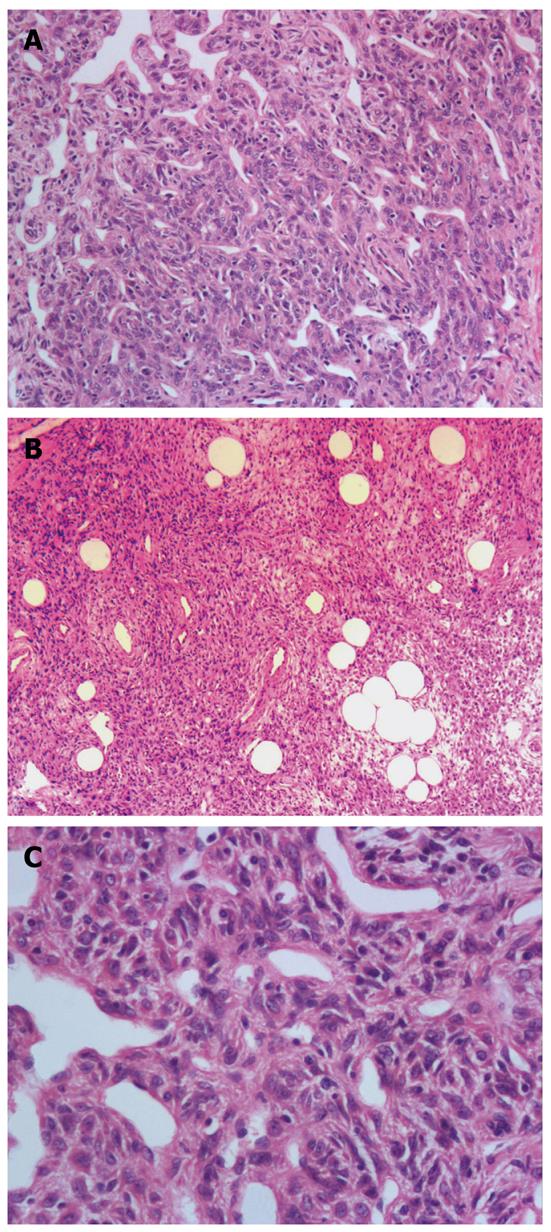

Histological examination revealed a submucosal well-circumscribed lesion composed of cellular nodules with the classic appearance of an HPC admixed with clusters and lobules of mature adipocytes. HPC-like areas showed a patternless architecture of oval to spindle cells surrounding the ectatic thin-walled branching vessels (staghorn configuration) (Figure 1A). The ill-defined tumor cells had weakly eosinophilic cytoplasm and contained spindled nuclei with occasional small nucleoli. Nuclei atypia and mitoses were absent, and no cellular atypia, necrosis, or vascular invasion was observed (Figure 1B). Mature, nonatypical adipocytes were identified throughout the lesion in varying proportions in various regions of the tumor, such as in lobules and foci of fat cells (Figure 1C). Focal myxoid changes were present.

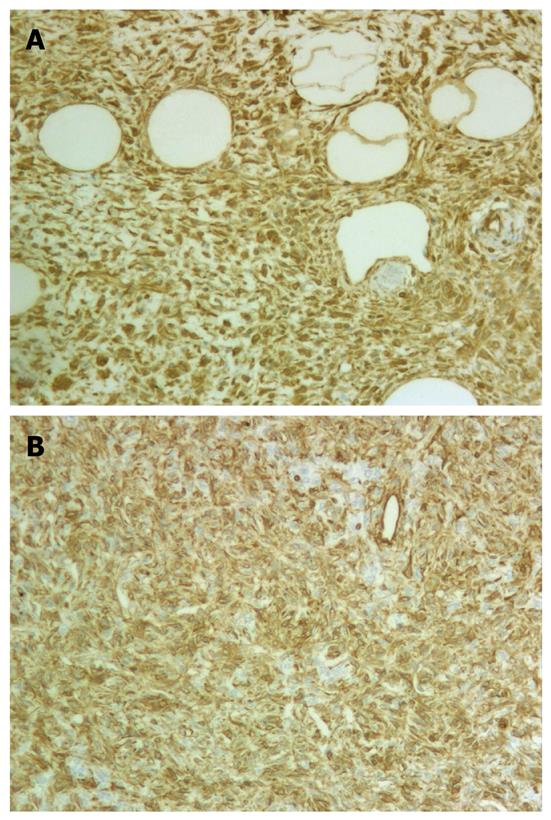

Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that the neoplastic oval and spindle (nonadipocytic) cells were strongly and diffusely positive for vimentin (Figure 2A), CD34 (Figure 2B), and CD99 and were focally reactive for bcl-2, whereas staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA), pankeratin, CD117, platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRA), HMB45, melan-A, and S-100 protein was negative. MIB-1 stained only approximately 1% of the tumor cells (1000 cells counted).

An LHPC, which was first formally described as a new entity in the 2002 edition of the WHO classification of soft-tissue tumors, is a rare hemangiopericytoma variant composed of mature adipocytes and hemangiopericytoma-like areas[20]. LHPC was first described as a unique hemangiopericytoma variant by Nielsen et al[1] and was named “LHPC” in the English language literature in 1995. In 2000, Guillou et al[4] noted that LHPCs and solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs) share similar clinical, pathological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural features, except for the presence of mature adipocytes in LHPC, and suggested that LHPC does not correspond to a well-defined entity but, rather, represents a fat-containing variant of SFT.

To date, a total of 50 pathologically confirmed cases of LHPC have been reported, including our patient[1-19]. Most lesions presented clinically as long-standing, deep-seated, indolent tumors, discovered fortuitously in some patients, whereas others had symptoms of compression related to tumor enlargement[4]. As documented in Table 1, LHPC seems to occur in middle-aged adult patients (range, 21-79 years; mean, 51.7 years), similar to the mean age of 55 years reported by Folpe et al[3]. The sex distribution for the LHPC cases for which this information is known is 20 females and 29 males, demonstrating a slight male predilection of LHPC. The size of the lesions ranged from 0.8 cm to 21 cm (mean, 7.9 cm). LHPCs have a wide anatomical distribution, but the most commonly affected sites are the lower extremities (14/50), including the thigh, hip, calf, popliteal fossa, and inguina. Other sites (72%) included the retroperitoneum, orbit, mediastinum, and pelvic cavity. The thigh, retroperitoneum and the orbit were the most commonly affected sites. Most of the tumors were located in the deep soft tissue[4].

Given that no LHPC patients developed recurrence during the follow-up interval and that all were without disease, some authors have concluded that LHPCs are likely to be benign tumors[3,4]. However, in our opinion, their biological behavior has yet to be determined because only 30 cases have been followed up in the English language literature to date, and the mean follow-up length was only 30.5 mo, not long enough to draw definitive conclusions about the prognosis of LHPCs. Davies et al[5] suggested that patients with LHPC should be followed up for more than 10 years.

Grossly, LHPC generally presents as a well-demarcated, variably encapsulated, medium-sized mesenchymal tumor. Cut sections show alternating areas of whitish and yellowish tumor tissue, in most cases with a lobular or fascicular appearance. Microscopically, the tissue characteristically shows a varying combination of cellular areas composed of round to spindle cells, collagenous or myxoid stroma with focal sclerotic areas, hemangiopericytoma-like vasculature made of small- to medium-sized thick-walled branched vessels, and lipomatous areas made up of mature adipocytes[4]. LHPCs may become large and occasionally show nuclear atypia within sclerotic zones, a phenomenon probably akin to that seen in degenerated schwannomas. LHPCs may also rarely show foci of high cellularity but do not approach the level seen in malignant LHPCs or in other malignancies that commonly show a hemangiopericytomatous pattern, such as synovial sarcoma or mesenchymal chondrosarcoma[3]. Immunohistochemistry showed that the nonadipocytic tumor cells are strongly and diffusely positive for vimentin and CD34, and they can also be positive for CD99 and bcl-2[21]. Ultrastructurally, the nonadipocytic tumor cells show features consistent with fibroblastic, myofibroblastic or pericytic differentiation[21].

Considering the location and histological appearance of this type of tumor, the main differential diagnoses considered should include GIST, angiomyolipoma, liposarcoma, and spindle cell lipoma (SCL). The stomach is the most common location for GIST, with 60%-70% of tumors occurring in this location[22]. In fact, in our study, the initial clinical diagnosis was GIST. Briefly, GISTs contain bundles of spindle cells and do not contain the mature adipocytes characteristic of LHPC. LHPCs are positive for CD34 but are negative for CD117. In contrast, GISTs are positive for CD117, CD34, and PDGFRA[23]. There was consistent negative staining for CD117 and PDGFRA. Hence, the tumor was not a GIST but, judging by its histological and immunohistochemical features, an LHPC. Differentiating an angiomyolipoma, especially one with a prominent smooth muscle component, from an LHPC is based on the former’s distinctive arrangement of the spindle cells around thick-walled vessels and their immunoreactivity for SMA and melanocytic markers (HMB45 and melan-A)[4,9]. Liposarcoma, especially the myxoid variant, can have a prominent vasculature. The vascular configuration should serve as a useful clue in distinguishing between liposarcoma and LHPC. The vessels in myxoid liposarcoma form a delicate plexiform capillary vascular network, unlike the staghorn pattern of LHPC. Furthermore, LHPCs are devoid of lipoblasts[1]. SCL usually develops in the subcutaneous tissue of the neck and upper back of male patients and contains short bundles of wiry collagen admixed with the spindle cells. SCLs do not contain the hemangiopericytoma-like vasculature of LHPCs[21].

In conclusion, the clinicopathological features of our case were entirely compatible with those of LHPC, and to our knowledge, this is the first reported case affecting the stomach. More cases of LHPC of the stomach must be studied to draw definitive conclusions about its distinct behavior and management.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Francesco Franceschi, Department of Internal Medicine, Catholic University of Rome, Largo A Gemelli, 8, Rome 00168, Italy

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Nielsen GP, Dickersin GR, Provenzal JM, Rosenberg AE. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma. A histologic, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a unique variant of hemangiopericytoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:748-756. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ceballos KM, Munk PL, Masri BA, O'Connell JX. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: a morphologically distinct soft tissue tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:941-945. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Folpe AL, Devaney K, Weiss SW. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: a rare variant of hemangiopericytoma that may be confused with liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1201-1207. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Guillou L, Gebhard S, Coindre JM. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: a fat-containing variant of solitary fibrous tumor? Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural analysis of a series in favor of a unifying concept. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1108-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Davies PE, Davis GJ, Dodd T, Selva D. Orbital lipomatous haemangiopericytoma: an unusual variant. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2002;30:281-283. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Manuel Lopes J, Villanueva JP, Gil-Gil P, Sobrinho-Simões M. Lipomatous haemangiopericytoma (adipocytic variant of solitary fibrous tumour) of the thyroid. Histopathology. 2003;43:406-408. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Domanski HA. Fine-needle aspiration smears from lipomatous hemangiopericytoma need not be confused with myxoid liposarcoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:287-291. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Alrawi SJ, Deeb G, Cheney R, Wallace P, Loree T, Rigual N, Hicks W, Tan D. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma of the head and neck: immunohistochemical and DNA ploidy analyses. Head Neck. 2004;26:544-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamaguchi T, Takimoto T, Yamashita T, Kitahara S, Omura M, Ueda Y. Fat-containing variant of solitary fibrous tumor (lipomatous hemangiopericytoma) arising on surface of kidney. Urology. 2005;65:175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Verfaillie G, Perdaens C, Breucq C, Sacre R. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma of the axilla. Breast J. 2005;11:211. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Amonkar GP, Deshpande JR, Kandalkar BM. An unusual lipomatous hemangiopericytoma. J Postgrad Med. 2006;52:71-72. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Shaia WT, Bojrab DI, Babu S, Pieper DR. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma of the skull base and parapharyngeal space. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:560-563. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Farah-Klibi F, Ferchichi L, Zaïri I, Rammeh S, Adouani A, Jilani SB, Zermani R. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma (adipocytic variant of solitary fibrous tumor) of the orbit. A case report with review of the literature. Pathologica. 2006;98:645-648. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Yamazaki K, Eyden BP. Pulmonary lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: report of a rare tumor and comparison with solitary fibrous tumor. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2007;31:51-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pitchamuthu H, Gonzalez P, Kyle P, Roberts F. Fat-forming variant of solitary fibrous tumour of the orbit: the entity previously known as lipomatous haemangiopericytoma. Eye (Lond). 2009;23:1479-1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim MY, Rha SE, Oh SN, Lee YJ, Byun JY, Jung CK, Kang WK. Case report. Lipomatous haemangiopericytoma (fat-forming solitary fibrous tumour) involving the perineum: CT and MRI findings and pathological correlation. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:e23-e26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dozois EJ, Malireddy KK, Bower TC, Stanson AW, Sim FH. Management of a retrorectal lipomatous hemangiopericytoma by preoperative vascular embolization and a multidisciplinary surgical team: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1017-1020. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Aftab S, Casey A, Tirabosco R, Kabir SR, Saifuddin A. Fat-forming solitary fibrous tumour (lipomatous haemangiopericytoma) of the spine: case report and literature review. Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39:1039-1042. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Liu X, Zhang HY, Bu H, Meng GZ, Zhang Z, Ke Q. Fat-forming variant of solitary fibrous tumor of the mediastinum. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi (Engl). 2007;120:1029-1032. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Guillou L, Fletcher JA, Fletcher CDM. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumour and haemangiopericytoma. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press 2002; 86-90. |

| 21. | Guillou L, Coindre JM. Newly described adipocytic lesions. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2001;18:238-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Negreanu LM, Assor P, Mateescu B, Cirstoiu C. Interstitial cells of Cajal in the gut--a gastroenterologist's point of view. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6285-6288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bayraktar UD, Bayraktar S, Rocha-Lima CM. Molecular basis and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2726-2734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |