Published online Nov 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i43.4804

Revised: May 18, 2011

Accepted: May 25, 2011

Published online: November 21, 2011

AIM: To investigate the appropriate time for combination therapy in HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

METHODS: Thirty HBeAg positive CHB patients with decompensated cirrhosis were enrolled in the study. All of the patients were given 48 wk combination therapy with lamivudine (LAM) and adefovir dipivoxil (ADV). Briefly, 10 patients were given the de novo combination therapy with LAM and ADV, whereas the other 20 patients received ADV in addition to LAM after hepatitis B virus (HBV) genetic mutation.

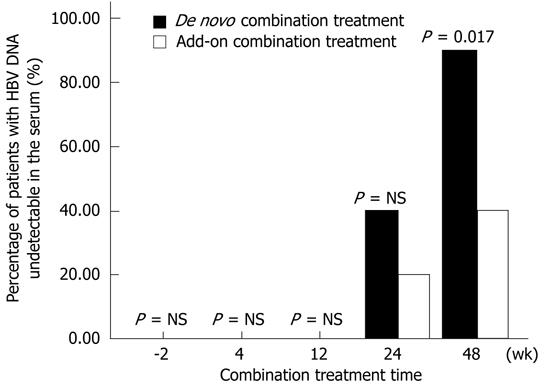

RESULTS: Serum alanine aminotransferase and total bilirubin were both improved in the two groups at 4, 12, 24 and 48 wk after treatment. Serum albumin was also improved at 24 and 48 wk after combination therapy in both groups. The serum HBV DNA level was still detectable in every patient in the two groups at 4 and 12 wk after combination treatment. However, in the de novo combination group, serum HBV DNA levels in 4 (40%) and 9 (90%) patients was decreased to below 1×103 copies/mL at 24 and 48 wk after the combination treatment, respectively. In parallel, serum HBV DNA levels in 2 (20%) and 8 (40%) patients in the add-on combination group became undetectable at 24 and 48 wk after combination treatment, respectively. Furthermore, 6 (60%) patients in the de novo combination group achieved HBeAg seroconversion after 48 wk treatment, whereas only 4 (20%) patients in the add-on combination group achieved seroconversion. Child-Pugh score of patients in the de novo combination group was better than that of patients in the add-on combination group after 48 wk treatment. Moreover, patients in the de novo combination group had a significantly decreased serum creatinine level and elevated red blood cell counts.

CONCLUSION: De novo combination therapy with LAM and ADV was better than add-on combination therapy in terms of Child-Pugh score, virus inhibition and renal function.

-

Citation: Fan XH, Geng JZ, Wang LF, Zheng YY, Lu HY, Li J, Xu XY.

De novo combination therapy with lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil in chronic hepatitis B patients. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(43): 4804-4809 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i43/4804.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i43.4804

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is prevalent world-widely. World Health Origination estimates that approximately 400 million people are chronic HBV carriers around the world[1]. Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is a leading cause of hepatic cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1]. Once cirrhosis develops, mortality is high in untreated patients. The 5 years mortality rate of CHB patients with decompensated cirrhosis is 86%[2]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop an effective therapy for those decompensated cirrhosis patients infected with chronic HBV.

The treatment for decompensated cirrhotic patients aims to delay the occurrence of HCC. Recommended therapy options are nucleos(t)ide analogues, such as lamivudine (LAM), adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) and entecavir (ETV). Previous studies showed that LAM is effective in cirrhotic patients infected with chronic HBV[3,4]. However, the clinical benefit of LAM is limited by the emergence of resistant mutant strains[5,6]. Recently, ADV has been strongly considered as a rescue therapeutic agent to resistant mutants[7,8]. Several studies showed that combination therapy with LAM and ADV is better than ADV monotherapy in LAM-resistant patients infected with HBV[7,9,10]. However, it remains unclear how to start the combination therapy in HBeAg positive patients with decompensated cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B. In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the better combination therapy in HBeAg positive patients with decompensated cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B.

Adult patients who had CHB with decompensated cirrhosis and HBeAg positive were enrolled in the study from January 2008 to June 2010 in Peking University First Hospital and Shijiazhuang Fifth Hospital. The criteria for diagnosis of hepatitis were those which appear in the guidelines for prevention and treatment of CHB in China[11]. The diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis was based on clinical, laboratory, previous histological, ultrasonographic and radiological signs of cirrhosis with at least one sign of liver decompensation (ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, non-obstructive jaundice). Patients co-infected with hepatitis A virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, hepatitis E virus, or human immunodeficiency virus and with alcoholic cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis, hepatorenal syndrome, HCC or severe heart, brain, renal diseases were excluded from the study. All of the patients were both HBV DNA and HBeAg positive. A total of 30 patients were enrolled in the study. Child-Pugh score was used to assess the clinical status of every patient[12]. Sixteen patients were at B stage (mean score: 8.4), and the other 14 patients were at C stage (mean score: 11.1).

All of the patients were given LAM (100 mg/d QO, GSK, Suzhou, China) at the beginning of treatment. Ten of them were then given ADV 10 mg/d (QO, GSK, Suzhou, China) over the following 2 wk (de novo combination arm), while the other 20 patients received ADV 10 mg/d in addition to LAM after HBV genetic YMDD mutation (add-on combination arm). The duration of combination treatment was 48 wk for both arms.

Peripheral blood was taken from all of the patients in the morning with fasting for at least 8 h. HBsAg, HBsAg antibody (anti-HBs), HBeAg, HBeAg antibody (anti-HBe) and HBcAg antibody (anti-HBc) were detected by AxSYM MEI kits (Abbott Laboratories, United States). Serum HBV DNA level was measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Daan Gene Co., LTD of Sun Yan-sen University, Guangzhou, China) at certain time points (week 0, 4, 12, 24 and 48) during treatment. The detection limit of HBV DNA was 1×103 copies/mL.

Routine biochemical and hematological tests were performed at the participating centers using automated techniques at certain time points (week 0, 4, 12, 24 and 48) during treatment. Child-Pugh score was also assessed simultaneously.

Data were expressed as arithmetic mean ± SD, median (range), or frequency and percentage when appropriate. Student t test was used to analyze the normally distributed quantitative variables between the two study groups. Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to analyze the skewed data. All tests were two tailed, and P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were done using the SPSS 16.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Science; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) statistical software.

A total of 30 patients were enrolled in the study, including 17 males (56.7%) with a median age of 42 years (40-49 years). Data showed that serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin (TBIL) and albumin (ALB) levels at baseline in the de novo combination patients were significantly lower than those in the add-on combination patients. However, mean serum HBV DNA level and Child-Pugh score were not different between the two groups. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristic | De novo combination group (n = 10) | Add-on combination group (n = 20) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 45.6 ± 8.2 | 45.2 ± 8.2 | 0.89 |

| Gender (males,%) | 6 (60%) | 11 (55%) | 1 |

| Height (m) | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 0.58 |

| Weight (kg) | 68.9 ± 9.7 | 67.3 ± 10.5 | 0.69 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8 ± 1.8 | 23.7 ± 1.6 | 0.88 |

| HBV DNA levels (log10, copies/mL) | 6.23 ± 0.91 | 6.43 ± 0.95 | 0.58 |

| Serum ALT (IU/L) | 124 (82-156) | 283 (187-321) | 0 |

| Serum TBIL (μmol/L) | 49.5 (23-72) | 73.5 (49.0-99.6) | 0.001 |

| Serum ALB (g/L) | 29.75 (25.40-34.00) | 26.65 (23.00-32.00) | 0.021 |

| Child-Pugh score | 11 (9-13) | 11 (9-13) | 0.809 |

| Red blood cell counts (× 1012/L) | 3.6 (3.0-4.5) | 3.3 (1.9-5.0) | 0.234 |

| HB (g/L) | 106 (90-120) | 97 (75-115) | 0.059 |

| White blood cell counts (× 109/L) | 3.85 (2.70-6.80) | 3.75 (1.90-6.00) | 0.657 |

| Blood PLT count (× 109/L) | 96 (76-150) | 96 (50-112) | 0.657 |

| Serum BUN (mmol/L) | 6.05 (3.70-8.10) | 4.35 (1.90-8.50) | 0.139 |

| Serum Cr (μmol/L) | 99.5 (77.0-145.0) | 77.0 (40.0-156.0) | 0.024 |

The percentage of patients with undetectable HBV DNA in the de novo combination group was 0, 0, 40% and 90% at 4, 12, 24 and 48 wk after the treatment, respectively. However, it was 0, 0, 20% and 40% at each time point in the add-on combination group, respectively. Figure 1 shows that the percentage of patients with undetectable HBV DNA was significantly different between the two groups after the 48 wk treatment (P = 0.017). Moreover, no patient in the two groups showed detectable virological resistance during the 48 wk combination treatment.

We showed that ALT, TBIL and ALB of patients were decreased in the two groups after treatment. Furthermore, 6 (60%) patients in the de novo combination group achieved HBeAg seroconversion, whereas only 4 (20%) patients in the add-on combination group achieved seroconversion (P = 0.045).

Child-Pugh score at baseline was not statistically different in the two groups. Table 2 shows that Child-Pugh score in the de novo combination group was significantly lower than that in the add-on combination group after the 48 wk treatment.

| De novo combination group (n = 10) | Add-on combination group (n = 20) | |||||||||

| 2 wk before combination treatment | 4 wk after combination treatment | 12 wk after combination treatment | 24 wk aftercombinationtreatment | 48 wk after combination treatment | 2 wk before combination treatment | 4 wk after combination treatment | 12 wk after combination treatment | 24 wk after combination treatment | 48 wk after combination treatment | |

| Child-Pugh score | 11 (9-13) | 10 (8-12) | 10 (8-12) | 9 (7-11)c | 7 (6-9)ca | 11 (9-13) | 10 (9-12) | 10 (9-12) | 10 (7-11)c | 9 (7-10)c |

| Serum ALT (IU/L) | 124 (82-156)a | 111 (80-141)a | 109 (69-125)a | 89 (59-112)ca | 49 (28-67)ca | 283 (187-321) | 251 (171-302)c | 218 (146-277)c | 173 (105-239)c | 105 (65-186)c |

| Serum TBIL (μmol/L) | 49.5 (23-72)a | 47.3 (25.0-70.1)a | 41.3 (25.5-63.0)a | 37.8 (22.5-57.4)ca | 31.0 (22.0-41.0)ca | 73.5 (49.0-99.6) | 68.3 (44.5-88.7) | 63.5 (35.8-79.0)c | 56.7 (32.0-72.3)c | 41.2(29.0-58.1)c |

| Serum ALB (g/L) | 29.75(25.40-34.00)a | 30.15(27.20-34.10)a | 30.55(27.60-33.00)a | 32.80(29.00-35.00)ca | 34.00(30.00-37.00)ca | 26.65(23.00-32.00) | 28.20(25.60-32.90) | 27.85(25.00-31.90) | 28.75(25.50-33.00)c | 30.5(28.0-34.8)c |

Red blood cell counts and hemoglobin levels in the 2 groups showed no difference at baseline. However, red blood cell counts and hemoglobin in the de novo combination group were higher than those in the add-on combination group at 24 and 48 wk after treatment. White blood cell counts and platelet (PLT) level showed no difference between the two groups at baseline and during the treatment period.

Moreover, serum blood urine nitrogen (BUN) level was not different between the two groups at baseline and during treatment. Serum creatinine (Cr) at baseline in the de novo combination group was significantly higher than that in the add-on combination group. However, serum Cr level in the 2 groups was not significantly different after treatment (Table 3).

| De novo combination group (n = 10) | Add-on combination group (n = 20) | |||||||||

| 2 wk before combination treatment | 4 wk after combination treatment | 12 wk after combination treatment | 24 wk after combination treatment | 48 wk after combination treatment | 2 wk before combination treatment | 4 wk after combination treatment | 12 wk after combination treatment | 24 wk after combination treatment | 48 wk after combination treatment | |

| Red blood cell counts (× 1012/L) | 3.6 (3.0-4.5) | 3.4 (3.0-4.3) | 3.5 (2.9-4.1) | 3.6 (3.1-4.0)a | 3.8 (3.0-5.1)a | 3.3 (1.9-5.0) | 3.2 (2.3-4.1) | 3.1 (2.5-4.0) | 3.1 (2.5-3.9) | 3.1 (2.7-3.4)c |

| HB (g/L) | 106 (90-120) | 104 (92-113)a | 102 (99-115) | 107 (94-114)a | 105 (85-121)a | 97 (75-115) | 95 (80-114) | 95 (85-111) | 99 (88-112) | 97 (84-105) |

| White blood cell counts (× 109/L) | 3.85 (2.70-6.80) | 3.90 (2.90-5.70) | 3.80 (3.00-5.20) | 3.95 (3.20-4.70) | 4.00 (3.00-4.50) | 3.75 (1.90-6.00) | 3.75 (2.50-5.60) | 3.70 (2.90-5.00) | 3.75 (2.90-4.70) | 3.85 (3.00-5.10) |

| Blood PLT counts (× 109/L) | 96 (76-150) | 90 (72-100) | 94 (70-116) | 95 (68-108) | 98 (72-103) | 96 (50-112) | 94 (63-111) | 92 (76-110) | 90 (69-107) | 93 (73-112) |

| Serum BUN (mmol/L) | 6.05 (3.70-8.10) | 5.90 (3.00-7.40) | 5.65 (3.60-7.10) | 5.50 (2.50-6.80) | 5.45 (3.30-7.00) | 4.35 (1.90-8.50) | 5.25 (2.20-8.70) | 5.00 (2.20-8.00) | 5.00 (2.90-7.50) | 4.95 (2.30-7.10) |

| Serum Cr (μmol/L) | 99.5 (77.0-145.0)a | 96.5 (76.0-141.0) | 96.0 (69.0-112.0) | 78.0 (56.0-99.0)c | 78.5 (61.0-107.0)c | 77.0 (40.0-156.0) | 95.5 (61.0-124.0) | 86.0 (68.0-131.0) | 73.5 (42.0-132.0) | 79.0 (41.0-132.0) |

Both de novo combination treatment and add-on combination treatment were well tolerated. No patient in either group discontinued the drug during the period.

In the de novo combination group, serum BUN level of two patients was slightly increased, two patients had slight diarrhea, and one patient had nausea. In parallel, in the add-on combination group, serum BUN level of two patients was slightly increased, two patients had nausea, one patient had slight diarrhea, and one patient had upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. All these symptoms disappeared after relevant management.

In this retrospective study, we compared de novo combination therapy with add-on combination therapy in HBeAg positive and decompensated cirrhosis patients infected with HBV. The percentage of patients with undetectable HBV DNA was 40% (4/10) and 20% (4/20) in the de novo combination and add-on combination groups at 24 wk after treatment, respectively. However, this difference between two groups was not statistically different. The percentage of patients with undetectable HBV DNA in the de novo combination group (9/10, 90%) was significantly higher than that in the add-on combination group (8/20, 40%) at 48 wk after treatment. We, for the first time, compared de novo combination treatment with add-on combination treatment in cirrhotic decompensated patients secondary to hepatitis B. Some researchers compared LAM and ADV combination therapy with ADV monotherapy after LAM-induced viral genetic resistance. They showed that LAM and ADV combination therapy is a more effective treatment to get a virological response and has lower genetic resistance than ADV monotherapy[7-9]. However, the efficiency of LAM and ADV combination therapy in treatment naïve patients with decompensated cirrhosis remains unclear. In the present study, we showed that de novo combination therapy was more effective than add-on combination therapy in terms of virological response and HBeAg seroconversion. No patient achieved virological resistance during combination treatment in both two groups.

It is known that HBeAg seroconversion is accompanied by biochemical and histological regression of liver disease[13,14]. Our data showed that the percentage of HBeAg seroconversion in the de novo combination group (6/10, 60%) was significantly higher than that in the add-on combination group (4/20, 20%).

Due to its simplicity in clinical practice, Child-Pugh score has been widely applied as the prognostic marker in patients with decompensated cirrhosis[15,16]. Child-Pugh score is one of the risk factors for assessing patients with decompensated cirrhosis[17]. In this study, Child-Pugh score of all patients was significantly decreased in the two groups after 24 and 48 wk combination treatment. Child-Pugh score at baseline was not different between the two groups. However, the score in the de novo combination group was superior to that in the add-on combination group after 48 wk treatment. LAM and ADV combination therapy could improve clinical symptoms in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. But, de novo combination therapy was more effective in improving hepatic function than LAM and ADV combination therapy after genetic resistance.

ALT, TBIL and ALB of the patients were different at baseline between the two groups. However, these three parameters were all significantly decreased in the two groups during the treatment period. LAM and ADV combination therapy was an effective way to produce a biochemical response in CHB patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

It has been reported that ADV decreases renal function[18]. In our study, serum Cr and BUN levels of all patients were not increased during the treatment period. However, serum Cr level in the de novo combination group was significantly higher than that in the add-on combination group (104.0 ± 23.5 vs 83.0 ± 29.4, P < 0.05) at baseline. But serum Cr in the two groups was not different after the 48 wk treatment. Our data showed LAM and ADV combination therapy did not affect renal function during the treatment period. The de novo combination therapy could improve serum Cr level in the decompensated cirrhosis patients infected with chronic HBV.

Taken together, a higher percentage of patients with undetectable HBV DNA and HBeAg seroconversion was obtained from the de novo combination group than from the add-on combination group. Moreover, Child-Pugh score in patients with the de novo combination therapy was better than that in patients with the add-on combination therapy after 48 wk treatment. Therefore, HBeAg positive decompensated cirrhotic patients infected with chronic HBV should receive LAM and ADV combination therapy at the beginning of antiviral treatment.

In the present study, we have several shortcomings as follows. First, the number of subjects was small because the number of patients treated with de novo combination therapy was limited in China. Second, the period of the combination treatment was not long enough. Therefore, a larger number of subjects and longer treatment duration are required in our future study.

The mortality rate of chronic hepatitis B patients with decompensated cirrhosis is very high. Recommended therapy options are nucleos(t)ide analogues. But, the combination treatment option with nucleos(t)ide analogues for HBeAg positive patients with decompensated cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B is not very clear.

Combination therapy with lamivudine (LAM) and adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) is better than ADV monotherapy in LAM-resistant patients infected with hepatitis B virus. But in HBeAg positive patients with decompensated cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B, it remains unclear whether combination treatment at the beginning of therapy is better than add-on combination therapy. In this study, the authors demonstrate that de novo combination therapy is more effective than add-on combination therapy with LAM and ADV in HBeAg positive patients with decompensated cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B.

Some research showed that LAM and ADV combination therapy is more effective as a means to get a virological response and has lower genetic resistance than ADV monotherapy after LAM-induced viral genetic resistance. However, the efficiency of LAM and ADV combination therapy in naïve patients with decompensated cirrhosis is unclear. For the first time, this study compared de novo combination treatment with add-on combination treatment in the cirrhotic decompensated patients secondary to hepatitis B.

By understanding that de novo combination therapy is more effective than add-on combination therapy, this study may represent a future strategy in the treatment of HBeAg positive patients with decompensated cirrhosis secondary to chronic hepatitis B.

De novo combination treatment means combination treatment with two or more drugs from the beginning of the treatment. Child-Pugh score is a system to assess the disease stage for decompensated cirrhotic patients.

In this study, the authors have made an attempt to determine the effective time frame for combined therapy used in HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Though the study is limited to only 30 patients, it is novel and contributes a substantial amount of knowledge to the field.

Peer reviewer: Shashi Bala, PhD, Postdoctoral Associate, Department of Medicine, LRB 270L, 364 Plantation Street, UMass Medical School, Worcester, MA 01605, United States

S-Editor Tian L L-Editor O’Neill M E-Editor Li JY

| 1. | Lok AS. Chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1682-1683. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | de Jongh FE, Janssen HL, de Man RA, Hop WC, Schalm SW, van Blankenstein M. Survival and prognostic indicators in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive cirrhosis of the liver. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1630-1635. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, Tanwandee T, Tao QM, Shue K, Keene ON, Dixon JS, Gray DF, Sabbat J. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521-1531. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Villeneuve JP, Durantel D, Durantel S, Westland C, Xiong S, Brosgart CL, Gibbs CS, Parvaz P, Werle B, Trépo C. Selection of a hepatitis B virus strain resistant to adefovir in a liver transplantation patient. J Hepatol. 2003;39:1085-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nafa S, Ahmed S, Tavan D, Pichoud C, Berby F, Stuyver L, Johnson M, Merle P, Abidi H, Trépo C. Early detection of viral resistance by determination of hepatitis B virus polymerase mutations in patients treated by lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2000;32:1078-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Di Marco V, Marzano A, Lampertico P, Andreone P, Santantonio T, Almasio PL, Rizzetto M, Craxì A. Clinical outcome of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B in relation to virological response to lamivudine. Hepatology. 2004;40:883-891. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Perrillo R, Hann HW, Mutimer D, Willems B, Leung N, Lee WM, Moorat A, Gardner S, Woessner M, Bourne E. Adefovir dipivoxil added to ongoing lamivudine in chronic hepatitis B with YMDD mutant hepatitis B virus. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:81-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Peters MG, Hann Hw H, Martin P, Heathcote EJ, Buggisch P, Rubin R, Bourliere M, Kowdley K, Trepo C, Gray Df D. Adefovir dipivoxil alone or in combination with lamivudine in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:91-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 448] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vassiliadis TG, Giouleme O, Koumerkeridis G, Koumaras H, Tziomalos K, Patsiaoura K, Grammatikos N, Mpoumponaris A, Gkisakis D, Theodoropoulos K. Adefovir plus lamivudine are more effective than adefovir alone in lamivudine-resistant HBeAg- chronic hepatitis B patients: a 4-year study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:54-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee JM, Park JY, Kim do Y, Nguyen T, Hong SP, Kim SO, Chon CY, Han KH, Ahn SH. Long-term adefovir dipivoxil monotherapy for up to 5 years in lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:235-241. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association and Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. Guideline on prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B in China (2005). Chin Med J (Engl). 2007;120:2159-2173. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646-649. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Realdi G, Alberti A, Rugge M, Bortolotti F, Rigoli AM, Tremolada F, Ruol A. Seroconversion from hepatitis B e antigen to anti-HBe in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:195-199. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Fattovich G, Rugge M, Brollo L, Pontisso P, Noventa F, Guido M, Alberti A, Realdi G. Clinical, virologic and histologic outcome following seroconversion from HBeAg to anti-HBe in chronic hepatitis type B. Hepatology. 1986;6:167-172. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Forman LM, Lucey MR. Predicting the prognosis of chronic liver disease: an evolution from child to MELD. Mayo End-stage Liver Disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:473-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Papatheodoridis GV, Cholongitas E, Dimitriadou E, Touloumi G, Sevastianos V, Archimandritis AJ. MELD vs Child-Pugh and creatinine-modified Child-Pugh score for predicting survival in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3099-3104. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Ma H, Wei L, Guo F, Zhu S, Sun Y, Wang H. Clinical features and survival in Chinese patients with hepatitis B e antigen-negative hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1250-1258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang TT, Kitis G, Rizzetto M, Marcellin P, Lim SG, Goodman Z, Ma J. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B for up to 5 years. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1743-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 674] [Cited by in RCA: 678] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |