Published online Nov 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i42.4696

Revised: May 11, 2011

Accepted: May 18, 2011

Published online: November 14, 2011

AIM: To evaluate the management of pancreaticopleural fistulas involving early endoscopic instrumentation of the pancreatic duct.

METHODS: Eight patients with a spontaneous pancreaticopleural fistula underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with an intention to stent the site of a ductal disruption as the primary treatment. Imaging features and management were evaluated retrospectively and compared with outcome.

RESULTS: In one case, the stent bridged the site of a ductal disruption. The fistula in this patient closed within 3 wk. The main pancreatic duct in this case appeared normal, except for a leak located in the body of the pancreas. In another patient, the papilla of Vater could not be found and cannulation of the pancreatic duct failed. This patient underwent surgical treatment. In the remaining 6 cases, it was impossible to insert a stent into the main pancreatic duct properly so as to cover the site of leakage or traverse a stenosis situated downstream to the fistula. The placement of the stent failed because intraductal stones (n = 2) and ductal strictures (n = 2) precluded its passage or the stent was too short to reach the fistula located in the distal part of the pancreas (n = 2). In 3 out of these 6 patients, the pancreaticopleural fistula closed on further medical treatment. In these cases, the main pancreatic duct was normal or only mildly dilated, and there was a leakage at the body/tail of the pancreas. In one of these 3 patients, additional percutaneous drainage of the peripancreatic fluid collections allowed better control of the leakage and facilitated resolution of the fistula. The remaining 3 patients had a tight stenosis of the main pancreatic duct resistible to dilatation and the stent could not be inserted across the stenosis. Subsequent conservative treatment proved unsuccessful in these patients. After a failed therapeutic ERCP, 3 patients in our series developed superinfection of the pleural or peripancreatic fluid collections. Four out of 8 patients in our series required subsequent surgery due to a failed non-operative treatment. Distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy was performed in 3 cases. In one case, only external drainage of the pancreatic pseudocyst was done because of diffuse peripancreatic inflammatory infiltration precluding safe dissection. There were no perioperative mortalities. There was no recurrence of a pancreaticopleural fistula in any of the patients.

CONCLUSION: Optimal management of pancreaticopleural fistulas requires appropriate patient selection that should be based on the underlying pancreatic duct abnormalities.

- Citation: Wronski M, Slodkowski M, Cebulski W, Moronczyk D, Krasnodebski IW. Optimizing management of pancreaticopleural fistulas. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(42): 4696-4703

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i42/4696.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i42.4696

The pancreaticopleural fistula is a rare type of internal pancreatic fistula. Although the precise incidence is unknown, pancreaticopleural fistulas are reported to occur in approximately 0.4% of patients with pancreatitis[1]. These fistulas are most commonly associated with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis[1-3]. The pancreaticopleural fistula results from a disruption of a major pancreatic duct usually due to an underlying pancreatic disease. A ductal disruption on the anterior surface of the pancreas usually leads to pancreatic ascites, whereas the posterior ductal leakage might result in thoracic fluid collections. The pancreatic juice spreads retroperitoneally through the paths of least resistance, commonly through the aortic or esophageal hiatus.

The management of pancreaticopleural fistulas remains controversial. The timing of surgical and endoscopic intervention for a pancreaticopleural fistula is disputable. There are no definitive criteria that would allow accurate prediction which patients are likely to benefit from medical treatment and which patients should be offered early surgical intervention. Medical therapy of pancreaticopleural fistulas fails in 59%-69% of cases[1,3,4]. Additionally, unsuccessful conservative treatment is associated with an increased rate of complications[3,5]. Recently, endoscopic instrumentation has become the preferred treatment in pancreaticopleural fistulas and an apparently high rate of fistula resolution has been reported in the literature[4,6]. In light of these observations we used endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with stenting of the pancreatic duct as an initial treatment in patients with a pancreaticopleural fistula.

In this article we present our experience in the management of patients with pancreaticopleural fistulas who initially underwent endoscopic therapy.

Between January 2000 and February 2010, 10 patients with a spontaneous pancreaticopleural fistula presented to our department. Two patients who received primary surgical treatment for a pancreaticopleural fistula due to the surgeon’s preference were excluded from the study. The patient group consisted of 7 males and 1 female. The mean age of the patients was 48 years (range: 34-63 years).

The pancreaticopleural fistula was defined as a pleural effusion with amylase content above 1000 IU/L and protein level above 3.0 g/dL. The fistulous tract was additionally demonstrated with computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or ERCP in all the cases.

Medical records were reviewed retrospectively for each patient. The clinical manifestations, underlying pancreatic pathology, imaging appearance and management of the pancreaticopleural fistula were evaluated. Early response to therapy and long-term outcome were assessed.

We used ERCP with an intention to stent the main pancreatic duct as an initial treatment. ERCP was performed as early as possible after the recognition of amylase-rich pleural effusion. ERCP was carried out by the interventional endoscopists skilled in therapeutic endoscopy with several years of experience in pancreatic procedures. Failure of endoscopic treatment was deemed an indication to operative intervention. Our medical management of pancreaticopleural fistulas included diet restriction and enteral or parenteral nutrition. Enteral feeding was delivered through a feeding tube inserted endoscopically or under fluoroscopic guidance into the proximal jejunum. Somatostatin analogs were administered in selected patients. Medical treatment before the trial of ERCP was not used uniformly, but most patients received it following the endoscopic procedure. The pleural effusion was drained in the patients with severe dyspnea or infected fluid. The details of conservative treatment are summarized in Table 1.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | |

| NPO1 (d) | 19 (6) | 0 (22) | 7 (27) | 0 (26) | 6 (9) | 0 (25) | 8 (0) | 14 (22) |

| TPN1 (d) | - | 0 (17) | 0 (27) | 0 (25) | 4 (7) | 0 (26) | - | 0 (16) |

| EN1 (d) | 16 (6) | - | - | - | - | - | 5 (17) | 7 (12) |

| Somatostatin analog1 (d) | - | 0 (11) | 0 (25) | 0 (43) | - | - | - | 0 (11) |

| Pleural fluid management | TD-25 d | TD-4 d | T-twice, TD-11 d | T-1 time, TD-25 d | TD-3 d | T-4 times | TD-30 d | Diagnostic thoracentesis alone |

Time to fistula healing was calculated from the date of the initial ERCP till the day of normalization of amylase level in the pleural fluid or disappearance of pleural effusion on a chest X-ray or ultrasound.

Descriptive statistics were used including mean and range.

The pancreaticopleural fistula was most commonly a complication of underlying chronic pancreatitis or a late consequence of acute pancreatitis. Chronic pancreatitis had been symptomatic for a period between 2 mo and 10 years. In one case, a pancreaticopleural fistula developed in a patient who had a longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy (a modified Puestow procedure) for chronic pancreatitis 10 mo earlier. All the patients presented with a thoracic symptomatology and most patients had left-sided pleural effusion. The diagnosis was established by means of thoracentesis in each case showing a high amylase level in the pleural fluid sample. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients with a pancreaticopleural fistula are summarized in Table 2.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | |

| Age (yr) | 41 | 63 | 42 | 34 | 50 | 46 | 59 | 52 |

| Gender | M | F | M | M | M | M | M | M |

| Etiology | CP | CP | AP | CP | CP | CP | CP | CP |

| Alcohol abuse | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Presentation | Dyspnea | Dyspnea, abdominal pain, chest pain | Dyspnea | Dyspnea, abdominal pain, chest pain | Dyspnea | Dyspnea, abdominal pain | Dyspnea | Dyspnea |

| Location of pleural effusion | Left | Left | Right | Left | Left | Left | Left | Left |

| Pleural amylase (IU/L) | 6715 | 34 512 | 9716 | 13 000 | 2072 | 26 977 | 10 158 | 1830 |

| Serum amylase (IU/L) | 519 | 300 | 251 | 155 | 144 | 248 | 30 | 234 |

| Duration of symptoms | 4 wk | 2 wk | 2 wk | 8 wk | 1 wk | 1 wk | 6 d | 4 d |

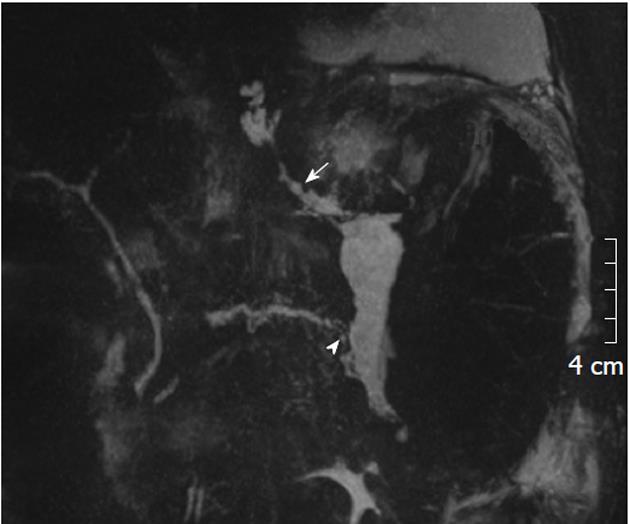

The fistulous tract was additionally visible in CT in 6 cases, in ERCP in 5 cases and in MRCP in 2 cases (Figures 1, 2 and 3). Imaging investigations revealed peripancreatic fluid collections in all patients. These collections were located along the fistulous tract that dissected into the mediastinum through the esophageal or aortic hiatus (Figure 1). The pancreas was usually of normal size with features of chronic pancreatitis. The imaging findings in the patients with a pancreaticopleural fistula are shown in Table 3.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | |

| Demonstration of fistulous tract | CT | ERCP, CT | CT | ERCP, CT | CT, MRCP | ERCP | ERCP, CT | ERCP, MRCP |

| Location of pleural effusion | Left | Left | Right | Left | Left | Left | Left | Left |

| CT | Enlarged pancreatic head, parenchymal calcifications, small peripancreatic fluid collections near the tail | Enlarged body and tail of the pancreas, peripancreatic fluid collections near the body and tail, dilated PD up to 6 mm | Pancreas not enlarged, PD dilated, small pseudocyst in the body | Pancreas not enlarged, small peripancreatic fluid collections near the tail, PD normal | Pancreas not enlarged, parenchymal calcifications, PD mildly dilated, small pseudocyst near the body and tail | Pancreas not enlarged, parenchymal calcifications in the head, PD dilated up to 3 mm, small pseudocyst near the tail | Pancreas not enlarged, PD normal, small pseudocyts near the pancreatic tail | Pancreas not enlarged, PD dilated up to 4 mm in the tail, pseudocyts near the pancreatic body and tail, ascites |

| MRCP | - | - | - | - | Pancreas not enlarged, PD dilated up to 3 mm in the body upstream to a stone, small pseudocysts near the tail | - | - | Pancreas not enlarged, PD normal, pseudocyts near the pancreatic body and tail, ascites, leak in the body |

ERCP with an intention to insert a stent so as to bridge the site of leak was performed as early as possible after the recognition of amylase-rich pleural effusion. In only one case, the stent bridged the site of leakage. The fistula in this patient closed within 3 wk following the procedure. The main pancreatic duct in this case appeared normal, except for a leak located in the body of the pancreas. In another patient, the papilla of Vater could not be found and cannulation failed. This patient underwent surgical treatment. In the remaining 6 cases, it was impossible to insert a stent into the main pancreatic duct properly so as to cover the site of leakage or traverse a stenosis situated downstream to the fistula. The placement of the stent failed because intraductal stones (n = 2) and ductal strictures (n = 2) precluded its passage or the stent was too short to reach the fistula located in the distal part of the pancreas (n = 2). In 3 out of these 6 patients, the pancreaticopleural fistula closed on further medical treatment. In these cases, the main pancreatic duct was normal or only mildly dilated, and there was a leakage at the body/tail of the pancreas. In one of these 3 patients, additional percutaneous drainage of the peripancreatic fluid collections allowed better control of the leakage and facilitated resolution of the fistula. This patient had two ductal disruptions in the body/tail of the pancreas and otherwise a normal main pancreatic duct. The stent was inserted so that it bridged the proximal ductal leak, but could not cover the second site of leakage which still supplied the fistula. The remaining 3 patients had a tight stenosis of the main pancreatic duct resistible to dilatation and the stent could not be inserted across the stenosis. Subsequent conservative treatment proved unsuccessful in these patients.

After a failed ERCP, 3 patients in our series developed superinfection of the pleural or peripancreatic fluid collections. Moreover, one of these patients developed a pancreaticobronchial fistula manifesting as left lobar pneumonia probably due to a prolonged chest tube drainage. The details of endoscopic treatment are summarized in Table 4.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | |

| Location of fistula | Tail | Body | Body | Body/tail | Tail | Body/tail | Body | Body/tail |

| ERCP | Dilated proximal PD, blockage of PD in the head due to intraductal stones | Ductal stricture and leak in the body | Cannulation not possible | No ductal stricture, leak in the tail | Normal proximal PD, blockage of PD in the body | No ductal stricture, leak in the body/tail | Ductal stricture in the body, leak within the stenotic duct | No ductal stricture, two leaks in the body/tail |

| ERCP | Failure (ductal blockage) | Failure (ductal stricture could not be dilated, stent not reached the stenosis and leak) | Failure (ampulla cannulation not possible) | Failure (stent not reached the site of leak, early stent migration) | Failure (ductal blockage precluding stenting) | Successful (stent bridging the site of leak) | Failure (ductal stricture could not be dilated, stent inserted up to the stricture) | Failure (stent bridging the site of one leak, but could not reach the site of the second leak) |

| Post-ERCP complications | - | Pleural empyema, infected peripancreatic fluid collection | - | Pleural empyema, pancreatitis flare-up | - | - | Pleural empyema, pneumonia, pancreatico-bronchial fistula, infected peripancreatic fluid collection | - |

| Post-ERCP treatment | Surgery | Surgery | Surgery | Conservative | Conservative | Conservative | Surgery | Percutaneous drainage of peripancreatic fluid collection |

| Time to fistula closure (d) | 30 | 25 | 28 | 11 | 24 | 17 | 26 | 34 |

Half of the patients in our series required surgical intervention after an unsuccessful attempt of endoscopic treatment. Distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy was performed in two cases. The patient after the Puestow operation underwent distal pancreatectomy with an end-to-end pancreaticojejunostomy. In one case, only external drainage of the pancreatic pseudocyst was done because of diffuse peripancreatic inflammatory infiltration. There were no perioperative mortalities. Postoperatively, two patients developed a pancreaticocutaneous fistula which closed spontaneously in one case and after the placement of an additional endoscopic stent in the other case.

The median follow-up was 13.5 mo (range: 5 mo-10 years). There were no recurrences of the pancreaticopleural fistula in any of the patients. The only patient in our series successfully managed with endoscopic treatment alone underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy 2 years later for intractable abdominal pain due to underlying chronic pancreatitis.

The diagnosis of a pancreaticopleural fistula is established when an amylase-rich fluid is drained on thoracentesis. There is not any established threshold of amylase level that is diagnostic of a pancreaticopleural fistula. We arbitrarily defined the pancreaticopleural fistula as a pleural effusion with an amylase content above 1000 IU/L. However, pleural effusions due to a pancreaticopleural fistula commonly show amylase level of many thousand units[1].

It is essential to evaluate the ductal anatomy and pancreatic morphology before planning further management. ERCP and MRCP are the commonly used modalities in the assessment of pancreatic fistulas. We discourage the use of ERCP as a first-line tool for confirmation of a pancreaticopleural fistula because of considerable risk of introducing infection. MRCP seems to be a better choice for the visualization of a pancreaticopleural fistula. This method enables recognition and outlining of both a fistula and the anatomy of the pancreatic ducts. Moreover, MRCP is a non-invasive study without the risk of superinfection or acute pancreatitis. It has been shown that MRCP detects pancreatic duct abnormalities and calculi with a similar accuracy to ERCP[7]. In contrast to ERCP, this study has the advantage of demonstrating the pancreatic duct upstream to the site of a complete obstruction, as it was the case in one of our patients. MRCP was helpful in the diagnosis of pancreaticopleural fistula in 80% of the cases, while ERCP and CT were useful in 78% and 47% respectively[2].

The role of conservative treatment and the timing of surgical or endoscopic intervention for a pancreaticopleural fistula is disputable. A 2-3-wk trial of medical therapy is traditionally recommended[1,5]. Failure of conservative treatment is considered an indication for endoscopic or surgical intervention. The success rate in resolution of a pancreaticopleural fistula on medical therapy alone has been reported to be of 31%-65%[1-3]. However, conservative treatment requires prolonged hospitalization and is costly. Moreover, failed medical treatment results in a higher rate of complications and significantly longer hospital stay[3]. In a series reported by Lipsett et al[5], 80% of deaths during non-operative management of internal pancreatic fistulas occurred in patients who had been treated conservatively for over 3 wk. Furthermore, pleural effusions left undrained for a long period might lead to the formation of lung entrapment, sequestrated pleural fluid collections or a pancreaticobronchial fistula. Therefore, the potential risks of prolonged medical treatment should always be weighted against the morbidity and mortality associated with operative treatment. The appropriate patient selection according to the ductal morphology visualized in MRCP might spare these 2-3 wk of conservative treatment in the cases with a poor chance of spontaneous fistula closure. In our series, only the fistulas that developed in patients with fairly normal pancreatic ducts responded well to medical treatment.

ERCP was initially used as a diagnostic tool. Nowadays, various therapeutic procedures can be performed at the time of ERCP. The armamentarium of interventional endoscopists includes pancreatic sphincterotomy, ductal stenting, nasopancreatic drainage and lithotripsy. Saeed et al[8] were first to report resolution of a pancreaticopleural fistula after endoscopic stenting of the pancreatic duct. Since then, there have been published multiple reports of successful closure of pancreaticopleural fistulas after endoscopic instrumentation of the pancreatic duct[4,6,9-12]. Nevertheless, endoscopic techniques carry the risk of serious complications such as acute pancreatitis, bleeding, perforation or septic complications. The complication rate of pancreatic endotherapy varies considerably and ranges from 7% to 25%[13-15]. Moreover, pancreatic endotherapy is technically demanding and requires substantial experience to avoid potentially life-threatening complications. Therefore, careful selection of patients is essential before endoscopic therapy is recommended.

We reviewed the management of pancreaticopleural fistulas based on the case reports and case series pub-lished between 1993 and 2009. Our search of the literature provided 30 cases of pancreaticopleural fistulas with adequately described ductal anatomy in ERCP and endoscopic treatment. Eight cases were treated medically following only a diagnostic ERCP. Most of these patients received total parenteral nutrition and a pancreatic enzyme inhibitor or somatostatin analog. Four out of the 8 pancreaticopleural fistulas healed on conservative treatment alone. The main pancreatic duct was normal or irregular without any obvious stricture in two of these cases and there was a ductal stenosis with a leak in the pancreatic tail in the remaining two cases. ERCP in all the 4 fistulas resistant to medical treatment revealed a downstream stricture of the pancreatic duct. Twenty cases were treated successfully with endoscopic instrumentation such as stent insertion (n = 16) or nasopancreatic drainage (n = 4). Sixteen out of 20 fistulas were located in the head or body of the pancreas. In 11 cases, there was only a ductal disruption without any significant stenosis of the main pancreatic duct. These patients were treated with a stent or nasopancreatic catheter placed across the site of leakage. In the remaining 9 cases, there was a concomitant ductal stricture that could be dilated and stented, although the stent or nasopancreatic catheter did not bridge the site of a ductal disruption in two cases. Another two patients underwent endoscopic instrumentation combined with extracorporeal lithotripsy due to intraductal stones. The reports of the pancreaticopleural fistulas after unsuccessful endotherapy did not provide adequate descriptions of the pancreatic duct anatomy.

The success rate of therapeutic endoscopy in pancreaticopleural fistulas is varied. Khan et al[6] successfully treated all 5 of their patients with a pancreaticopleural fistula by means of intraductal stenting. Similarly, Pai et al[14] reported a 96.4% success rate of endotherapy in the tre-atment of internal pancreatic fistulas, including 13 pancreaticopleural fistulas. However, most ductal disruptions in this series were located in the head and body of the pancreas (64.2%) and no leakage at the time of ERCP was found in 28.6% cases. Such proximal ductal disruptions are, however, more easily managed endoscopically. Varadarajulu et al[13] reported only a 55% success rate in resolution of the pancreatic duct disruption using a transpapillary stenting technique, although placement of a stent was possible in 95% of patients. However, it is noteworthy that 92% of the ductal disruptions that closed were in the cases where the stent bridged the site of leakage. In the remaining cases, the stent was put only close to the site of disruption (2%) or just across the ampulla (6%). In a series published by O’Toole et al[16] endotherapy used in internal pancreatic fistulas was successful in a third of their patients and there was a similar rate of both failed ductal cannulations and unsuccessful endoscopic treatment. Kaman et al[17] attempted placement of nasopancreatic drainage in six patients with an internal pancreatic fistula, but it failed in four patients due to ductal pathology. In their series, the fistula closed in only one patient. Similarly, endotherapy alone proved successful in just one case also in our series, and a partial success was seen in another patient. On the other hand, in some case series therapeutic endoscopy was not possible in most patients because of failed cannulation or stenting of the main pancreatic duct[18]. The duration of stent or nasopancreatic drainage is unknown, but most ductal disruptions resolve with a median time of 4-6 wk[14,15].

The majority of the pancreaticopleural fistulas that closed after endotherapy had a stent inserted so that it bridged the site of disruption. Shah et al[19] reported resolution of a pancreaticopleural fistula after exchange of a stent for a longer one that could bridge the site of disruption. Initial trial of a stent inserted only up to the site of disruption was unsuccessful in this case. It follows that a stent not only decreases the ductal pressure, but also plays a certain mechanical role in sealing the leakage. Decreasing ductal pressure may not be sufficient for resolution of a ductal disruption and coverage of the leak with a stent is required in some cases.

In our series, unsuccessful endotherapy resulted from the inability to cannulate the ampulla and failure to stent across the site of leakage or a downstream stenosis within the main pancreatic duct. The appropriate placement of a pancreatic stent for the treatment of a pancreaticopleural fistula requires coverage of the site of leakage or stenting across a stricture situated downstream to the fistula. Otherwise, endotherapy has to be considered unsuccessful and operative treatment should be performed early to prevent septic complications. In this series, the stent could not be inserted properly into the pancreatic duct because the papilla of Vater was not found (n = 1), intraductal stones (n = 2) and ductal strictures (n = 2) precluded passage of a stent or the stent was too short to reach the fistula located in the distal part of the pancreas (n = 2). In 3 out of these patients, the fistula closed on further medical treatment. In these cases, the main pancreatic duct was normal or only mildly dilated, except for a leakage located at the body/tail of the pancreas, what suggests a fairly good outflow of the pancreatic juice into the duodenum. In one of these 3 patients, additional percutaneous drainage of the peripancreatic fluid collections allowed better control of the leakage and facilitated resolution of the fistula. Therefore, the patients with a normal or mildly dilated main pancreatic duct without any downstream stenosis can receive a trial of conservative treatment, especially when the leakage is located in the pancreatic tail. The fistulas originating from the tail of the pancreas are usually low-output and more prone to spontaneous resolution. Endotherapy used in this patient group might further promote resolution of the fistula if a stent is inserted across the site of leakage. The patients with a downstream stricture or a fistula located in the head and body of the pancreas should preferably undergo endotherapy. However, a high rate of failure can be expected because of intraductal stones and strictures inherent to chronic pancreatitis that are often hard to dilatate due to severe fibrosis. In our series, the 3 patients with a tight stenosis of the main pancreatic duct could not be properly stented and conservative treatment used after ERCP was unsuccessful. After a failed ERCP, 3 patients in our series developed superinfection of the pleural or peripancreatic fluid collections. The pancreaticopleural fistula usually has a tortuous fistulous tract that connects with complex intraabdominal or thoracic fluid collections what renders them especially susceptible to infection. The patients after a failed ERCP should be treated operatively soon after the endoscopic procedure, preferably within the following 24-48 h. Any longer delay might lead to serious septic complications such as intra-abdominal abscess or pleural empyema and continued medical treatment usually fails. On the other hand, infected peripancreatic fluid collections after a failed therapeutic ERCP further complicate surgical dissection and sometimes external drainage is all that can be done in such a situation. Antibiotic prophylaxis might prevent some septic complications after ERCP. However, prophylactic antibiotics were not used in our series.

Before the era of therapeutic endoscopy, surgery was frequently used as a primary treatment in patients with pancreaticopleural fistulas. Nowadays, surgery is often seen as a treatment of the last resort and used only after failure of medical and endoscopic therapy. However, a delay in the definitive treatment of the cases having a poor chance of healing without surgical intervention might result in increased morbidity and mortality. On the other hand, pancreatic operations performed for a pancreaticopleural fistula have now acceptably low morbidity and mortality rates in the high-volume centers[18,20]. Moreover, early operative treatment is recommended in the institutions where there are no endoscopists experienced in the treatment of pancreatic diseases. Primary and early surgical treatment of pancreaticopleural fistulas might prove cost- and time-saving in appropriately selected patients and prevent life-threatening complications due to a failed ERCP, repeated thoracenteses or prolonged pleural drainage. In our series, 4 patients underwent surgical treatment after a failed endotherapy. Two of these patients had uncomplicated postoperative course. The other 2 patients developed a pancreaticocutaneous fistula. In contrast to internal pancreatic fistulas, the external fistulas can be managed conservatively for a long time because of a low risk of septic complications, and they often heal spontaneously.

The pancreaticopleural fistulas usually occur in pati-ents with chronic pancreatitis. Even though endotherapy may be initially successful, progression of the disease often leads to subsequent complications that frequently require surgical intervention. Therefore, surgical treatment might prove more effective for a longterm amelioration of the symptoms. In our series, one patient needed pancreatic resection because of intractable pain syndrome, although endotherapy had allowed resolution of the pancreaticopleural fistula 2 years earlier.

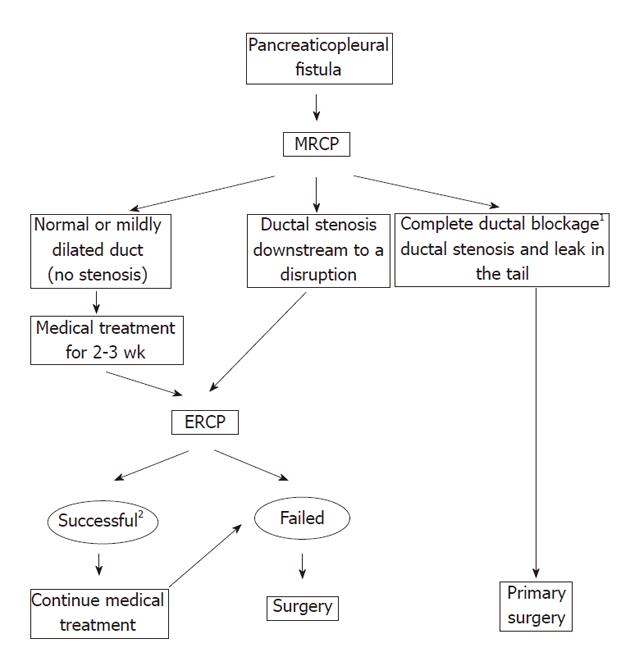

In conclusion, the choice of primary management in patients with pancreaticopleural fistulas should be tailored to the pancreatic ductal abnormalities. The patients with a normal or mildly dilated pancreatic duct without a downstream stenosis visualized on MRCP are optimally managed with a trial of medical treatment, especially when the leakage is located in the pancreatic tail. Ductal disruptions in the head and body of the pancreas and presence of a ductal stricture favor endoscopic treatment as a first-line therapy. Early surgical intervention is recommended whenever a stent cannot bridge the site of a ductal disruption or there is a downstream ductal stricture which can not be stented. Complete ductal obstruction anywhere along the main pancreatic duct or both a stricture and leakage within the pancreatic tail favor primary surgical treatment due to a poor chance of appropriate endoscopic stent placement. We propose an algorithm for the optimal management of pancreaticopleural fistulas (Figure 4).

The pancreaticopleural fistula is a rare type of internal pancreatic fistula. These fistulas are most commonly associated with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis and result from a disruption of a major pancreatic duct. The management options in pancreaticopleural fistulas include conservative treatment and endoscopic or surgical intervention.

The management of pancreaticopleural fistulas remains controversial. The timing of surgical and endoscopic intervention for a pancreaticopleural fistula is still disputable. There are no definitive criteria that would allow accurate prediction which patients are likely to benefit from medical treatment and which patients should be offered early surgical or endoscopic intervention. In the study, the role of early therapeutic endoscopy with stenting of the pancreatic duct was evaluated in regard to the pancreatic ductal anatomy.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with therapeutic intervention has recently become the preferred treatment in pancreaticopleural fistulas and an apparently high rate of fistula resolution has been reported in the literature. This study suggests that the choice of primary management in patients with pancreaticopleural fistulas should be tailored to the pancreatic ductal abnormalities.

The management of patients with pancreaticopleural fistulas can be improved with appropriate patient selection based on the pancreatic duct abnormalities. This selection is essential for the optimal treatment of pancreaticopleural fistula with low morbidity rate.

The paper addresses the important issues in management of pancreaticopleural fistulas.

Peer reviewers: Sundeep Singh Saluja, MS, MCh Assistant Professor, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, GB Pant Hospital and Maulana azad Medical College, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi 110002, India; Maha Maher Shehata, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Medical Specialized Hospital, Mansoura 35516, Egypt

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Rockey DC, Cello JP. Pancreaticopleural fistula. Report of 7 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1990;69:332-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ali T, Srinivasan N, Le V, Chimpiri AR, Tierney WM. Pancreaticopleural fistula. Pancreas. 2009;38:e26-e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | King JC, Reber HA, Shiraga S, Hines OJ. Pancreatic-pleural fistula is best managed by early operative intervention. Surgery. 2010;147:154-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Oh YS, Edmundowicz SA, Jonnalagadda SS, Azar RR. Pancreaticopleural fistula: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lipsett PA, Cameron JL. Internal pancreatic fistula. Am J Surg. 1992;163:216-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Khan AZ, Ching R, Morris-Stiff G, England R, Sherridan MB, Smith AM. Pleuropancreatic fistulae: specialist center management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:354-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sica GT, Braver J, Cooney MJ, Miller FH, Chai JL, Adams DF. Comparison of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with MR cholangiopancreatography in patients with pancreatitis. Radiology. 1999;210:605-610. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Saeed ZA, Ramirez FC, Hepps KS. Endoscopic stent placement for internal and external pancreatic fistulas. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1213-1217. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Koshitani T, Uehara Y, Yasu T, Yamashita Y, Kirishima T, Yoshinami N, Takaaki J, Shintani H, Kashima K, Ogasawara H. Endoscopic management of pancreaticopleural fistulas: a report of three patients. Endoscopy. 2006;38:749-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Miller JA, Maldjian P, Seeff J. Pancreaticopleural fistula. An unusual cause of persistent unilateral pleural effusion. Clin Imaging. 1998;22:105-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Neher JR, Brady PG, Pinkas H, Ramos M. Pancreaticopleural fistula in chronic pancreatitis: resolution with endoscopic therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:416-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hastier P, Rouquier P, Buckley M, Simler JM, Dumas R, Delmont JP. Endoscopic treatment of wirsungo-cysto-pleural fistula. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:527-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Varadarajulu S, Noone TC, Tutuian R, Hawes RH, Cotton PB. Predictors of outcome in pancreatic duct disruption managed by endoscopic transpapillary stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:568-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pai CG, Suvarna D, Bhat G. Endoscopic treatment as first-line therapy for pancreatic ascites and pleural effusion. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1198-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Telford JJ, Farrell JJ, Saltzman JR, Shields SJ, Banks PA, Lichtenstein DR, Johannes RS, Kelsey PB, Carr-Locke DL. Pancreatic stent placement for duct disruption. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:18-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | O'Toole D, Vullierme MP, Ponsot P, Maire F, Calmels V, Hentic O, Hammel P, Sauvanet A, Belghiti J, Vilgrain V. Diagnosis and management of pancreatic fistulae resulting in pancreatic ascites or pleural effusions in the era of helical CT and magnetic resonance imaging. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2007;31:686-693. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kaman L, Behera A, Singh R, Katariya RN. Internal pancreatic fistulas with pancreatic ascites and pancreatic pleural effusions: recognition and management. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:221-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Olakowski M, Mieczkowska-Palacz H, Olakowska E, Lampe P. Surgical management of pancreaticopleural fistulas. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109:735-740. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Shah HK, Shah SR, Maydeo AP, Pramesh CS. Pancreatico-pleural fistula. Endoscopy. 1998;30:314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Issekutz A, Makay R, Banga P, Németh A, Olgyai G. [Treatment of pancreaticopleural fistulas]. Zentralbl Chir. 2004;129:130-135. [PubMed] |