Published online Nov 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i41.4625

Revised: June 20, 2011

Accepted: June 27, 2011

Published online: November 7, 2011

AIM: To analyze the clinicopathologic features and the prognosis of primary intestinal lymphoma.

METHODS: Patients were included in the study based on standard diagnostic criteria for primary gastrointestinal lymphoma, and were treated at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre between 1993 and 2008.

RESULTS: The study comprised 81 adults. The most common site was the ileocaecal region. Twenty-two point two percent patients had low-grade B-cell lymphoma. Fifty-one point nine percent patients had high-grade B-cell lymphoma and 25.9% patients had T-cell lymphoma. Most patients had localized disease. There were more patients and more early stage diseases in the latter period, and the origin sites changed. The majority of patients received the combined treatment, and about 20% patients only received nonsurgical therapy. The wverall survival and event-free survival rates after 5 years were 71.6% and 60.9% respectively. The multivariate analysis revealed that small intestine and ileocaecal region localization, B-cell phenotype, and normal lactate dehydrogenase were independent prognostic factors for better patient survival. Surgery based treatment did not improve the survival rate.

CONCLUSION: Refined stratification of the patients according to the prognostic variables may allow individualized treatment. Conservative treatment may be an optimal therapeutic modality for selected patients.

- Citation: Wang GB, Xu GL, Luo GY, Shan HB, Li Y, Gao XY, Li JJ, Zhang R. Primary intestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A clinicopathologic analysis of 81 patients. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(41): 4625-4631

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i41/4625.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i41.4625

In the recent years, the incidence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) has increased worldwide, especially for primary extranodal lymphoma (ENL). Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma (PGIL) is the commonest ENL, which accounts for 30%-45% of ENL. Gastric lymphoma is the most frequent (55%-70%), followed by intestinal lymphoma (20%-35%), and colorectal lymphoma (5%-10%)[1].

Due to a lack of characteristic symptoms and a low incidence rate, primary intestinal lymphoma (PIL) is easily misdiagnosed until serious complications occur, such as perforation and ileus. Furthermore, the optimal treatment for PIL remains controversial, and the prognosis is unsatisfactory. Although during the past two decades, the diagnosis and treatment of PGIL has changed tremendously, results from studies of gastric lymphoma are controversial regarding the benefit of surgical resection[2-4]. However, a large-scale prospective investigation of PIL is difficult due to its low incidence and complicated histologic subtypes.

Numerous retrospective studies report the PGIL in European countries[5-7], but there were no large-sample studies from Asia in this decade besides Japan[8]. Our study consisted of 81 Chinese patients with PIL who were diagnosed and treated at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre between 1993 and 2008. It was a single center study, which retrospectively analyzed the clinical features, anatomic and histologic distribution, time trends and the prognosis of the PIL in Chinese patients.

This study consisted of 81 adult Chinese patients with PIL who were diagnosed and treated at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre between 1993 and 2008. Patients were included in the study based on standard diagnostic criteria for PGIL; patients had to present gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms or predominant lesions in the GI tract[9]. The patients who presented with second malignancies, had missing confirmation of histologic subtype, or had no follow-up information were excluded from the study.

The diagnostic workup included: details of the patients’ history and physical examination with inspection of Waldeyer’s ring, blood cell count, serum chemistry, chest radiographs, abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen, bone marrow aspiration or biopsy, and endoscopy examination with multiple biopsy. Endoscopic ultrasound and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT were carried out when available.

The histologic specimens were obtained by endoscopic biopsy or surgery. These specimens were stained routinely with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunohistochemical staining for CD3 and CD20 was performed on all 81 specimens. In some selected cases, additional staining and polymerase chain reaction-based amplifications of genes for immunoglobulin heavy chain or T-cell receptor gamma chain were done. All slides were reviewed separately by two pathologists and a common consensus was reached in all cases. Histologic classification was done according to WHO criteria[10].

Patients were then staged according to the Ann Arbor system with modifications[11].

The treatment modalities included surgical resection, conservative treatment (chemotherapy and radiotherapy), and the combined treatment. The main first line chemotherapy were four to six cycles of cyclophosphamide (CHOP) 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2, and vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 (maximum, 2mg) each on day 1, plus prednisone 100 mg on days 1 to 5) or RCHOP (rituximab 375 mg/m2 on day 0, plus CHOP). The regimen of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate (CODOX-M), alternating with ifosfamide, etoposide and high-dose cytarabine (IVAC), were used for patients with Burkitt’s lymphoma[12].

International Workshop Criteria was used for response evaluation. Therapeutic response after the initial treatment was designated as complete remission (CR), partial remission, stable disease, or progression of disease.

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to the date of death for any reason or to the last follow-up. Event-free survival (EFS) was measured from the date of diagnosis to the date that event occurred. Events included disease progression, relapse and patient death for any reason.

The statistical differences were evaluated using the Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U test (rank sum test) and the χ2 test. Survival curves were calculated according to the Kaplan-Meier method, and the value was compared using the log rank test. All variables that influenced the prognosis (P < 0.10) were put into a multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model. Differences were considered significant if the P-value was < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Software Package for the Social Sciences version 17.0 (SPSS 17.0).

From January 1993 to December 2008, 81 patients with PIL were recruited for the study. The patients had a mean age of 46 years (range, 18-75 years) and comprised of 58 men and 23 women.

The clinical symptoms of PIL were unspecific. Pain was the main diagnostic symptom in most cases (75.3%), followed by hematochezia (25.9%) and diarrhea (16.9%). Palpable mass, constipation and loss of appetite were less common symptoms. Perforation was scarce (7.4%). “B” symptoms occurred in 42.0% patients.

Most patients had localized disease. Sixty-six (81.5%) patients had Stage I~II disease and 15 (18.5%) had Stage III~IV disease. Most patients (75.3%) received the combined treatment, while about one fifth of patients only received nonsurgical therapy. The clinical features are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Number of patients (n = 81) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 58 (71.6) |

| Female | 23 (28.4) |

| Histology | |

| Low-grade B-cell | 18 (22.2) |

| High-grade B-cell | 42 (51.9) |

| T cell | 21 (25.9) |

| Stage | |

| I~II | 66 (81.5) |

| III~IV | 15 (18.5) |

| Treatment | |

| Surgery alone | 3 (3.7) |

| Nonsurgical | 16 (19.8) |

| Both | 61 (75.3) |

| No | 1 (1.2) |

| Treatment response | |

| Complete remission | 56 (69.1) |

| Partial remission | 7 (8.6) |

| Stable disease | 3 (3.7) |

| Progression | 15 (18.5) |

The origins of PIL were confirmed by surgery, endoscopy, or CT. They were subdivided as follows: (1) duodenum; (2) jejunum; (3) ileum; (4) ileocaecal region; (5) colon; (6) rectum; and (7) multiple sites. The ileocaecal region was defined as involvement of terminal ileum, cecum, appendix and or lower part of ascending colon. The most common site of PIL was the ileocaecal region (38.3%), followed by the colon (24.7%) and 13.6% small intestine (Table 2).

| Sites of origin | Number of patients (n = 81) |

| Duodenum | 2 (2.5) |

| Jejunum | 4 (4.9) |

| Ileum | 5 (6.2) |

| Ileocaecal region | 31 (38.3) |

| Colon | 20 (24.7) |

| Rectum | 8 (9.9) |

| Multiple sites | 11 (13.6) |

PIL are heterogeneous diseases. In the current study, B cell NHL and T-cell NHL were both classified into five common subtypes. The B cell subtypes, arranged by order, were: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) 35 (43.2%), marginal zone B-cell lymphoma 15 (18.5%), Burkitt and Burkitt-like lymphoma 4 (4.9%), follicular lymphoma 3 (3.7%), and mantle cell lymphoma 3 (3.7%). The ranks of the T cell subtypes were: enteropathy-type T cell lymphoma 7 (8.6%), peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified 5 (6.2%), uncertain subtype 5 (6.2%), anaplastic 3 (3.7%), and NK/T 1 (1.2%). All types of intestinal lymphoma showed broadly similar patterns in both sexes, apart from marginal zone lymphoma (MALT) which was predominant in women (9 in 23, 39.1%) (Table 3).

| Histologic type | Patients | Total(n = 81) | |

| Male(n = 58) | Female(n = 23) | ||

| B cell | 42 (72.4) | 18 (78.3) | 60 (74.1) |

| MALT | 6 (10.3) | 9 (39.1) | 15 (18.5) |

| Follicular lymphoma | 3 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.7) |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 3 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.7) |

| DLBCL | 27 (46.6) | 8 (34.8) | 35 (43.2) |

| Burkitt-like | 2 (3.4) | 1 (4.3) | 3 (3.7) |

| Burkitt lymphoma | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) |

| T cell | 16 (27.6) | 5 (21.7) | 21 (25.9) |

| ETCL | 6 (10.3) | 1 (4.3) | 7 (8.6) |

| Anaplastic | 3 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.7) |

| NK/T | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (1.2) |

| PTCL, NOS | 4 (6.9) | 1 (4.3) | 5 (6.2) |

| Others | 3 (5.2) | 2 (8.7) | 5 (6.2) |

The study was divided into two 8 year periods due to the use of Rituximab after 2000. Twenty-seven (33.3%) patients belonged to Period A, and 54 (66.7%) to Period B. Over these two periods, the average age of patients didn’t change (43.9 years vs 47.2 years, P = 0.454). The sites of origin were different (P = 0.0469), whereas the histology differences were not significant (P = 0.4975). More patients were in the early stage in period B (P < 0.0001), however the treatment and response did not change significantly (P = 0.686 vs P = 0.6842, respectively).

The follow-up after the diagnosis ranged from 18 to 183 mo (mean, 72 mo). The OS and EFS rates after 5 years were 71.6% and 60.9% respectively. Prognostic factors on univariate analysis were shown in Table 4.

| Characteristics | n = 81 | 5-year EFS | P value | 5-year OS | P value |

| Age | |||||

| 59 or younger | 70 | 56.1 | 0.939 | 68.9 | 0.852 |

| 60 or older | 11 | 56.8 | 68.4 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 58 | 56.4 | 0.843 | 62.3 | 0.058 |

| Female | 23 | 56.2 | 85.6 | ||

| Sites of origin | |||||

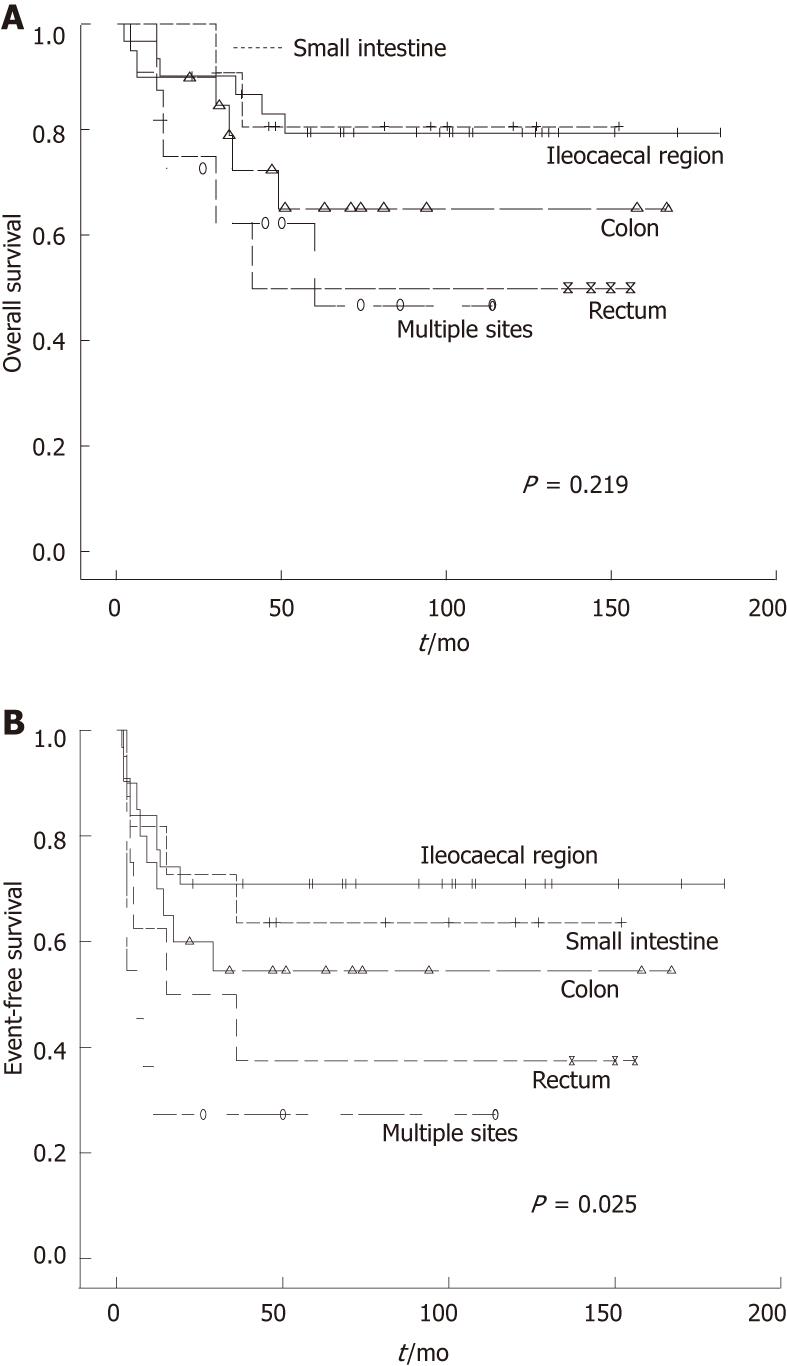

| Small intestine | 11 | 63.6 | 0.025 | 80.8 | 0.219 |

| Ileocaecal region | 31 | 71.0 | 79.6 | ||

| Colon | 20 | 54.5 | 65.2 | ||

| Rectum | 8 | 37.5 | 50.0 | ||

| Multiple sites | 11 | 27.3 | 46.8 | ||

| Histology | |||||

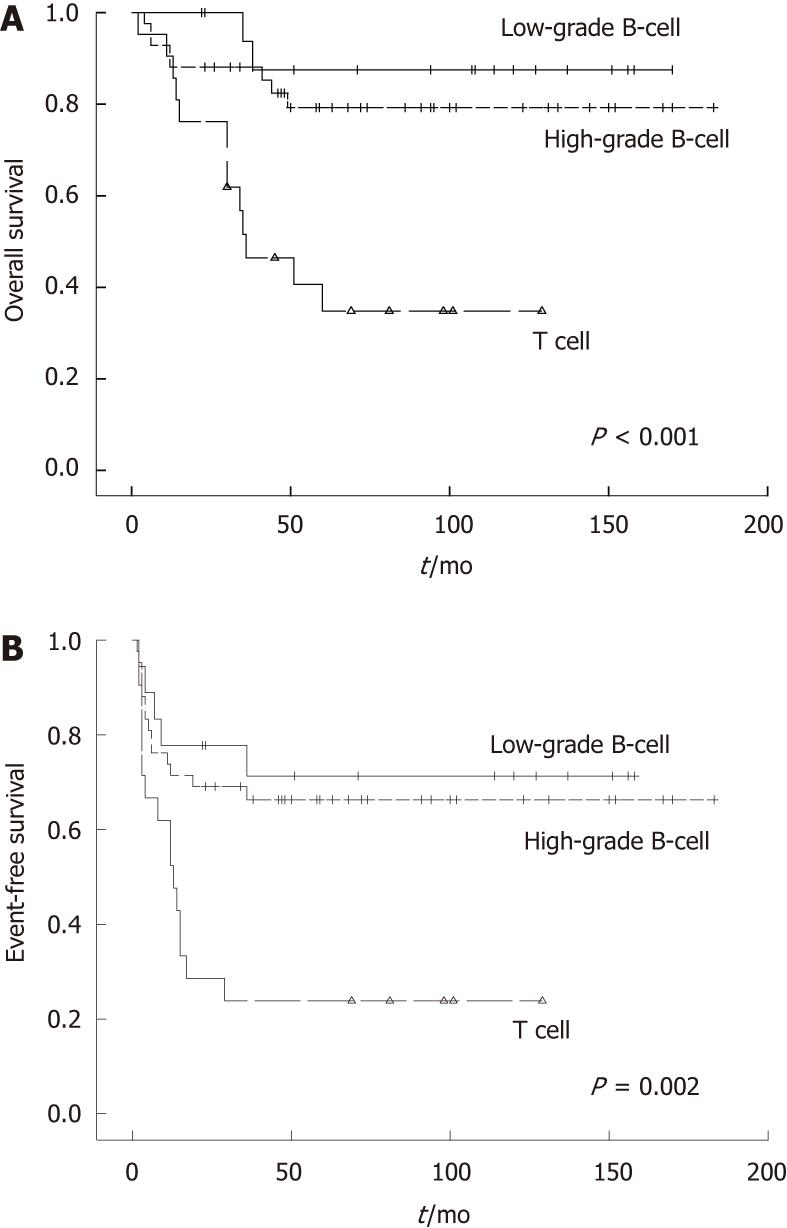

| Low-grade B-cell | 18 | 66.3 | 0.002 | 87.5 | < 0.001 |

| High-grade B-cell | 42 | 71.3 | 79.2 | ||

| T cell | 21 | 23.8 | 34.8 | ||

| Stage | |||||

| I~II | 66 | 58.8 | 0.387 | 69.0 | 0.727 |

| III~IV | 15 | 45.7 | 71.4 | ||

| Bulky disease | |||||

| < 8 cm | 54 | 60.6 | 0.189 | 70.1 | 0.837 |

| ≥ 8 cm | 27 | 48.1 | 67.7 | ||

| Perforation | |||||

| Yes | 6 | 28.6 | 0.074 | 25.0 | 0.024 |

| No | 75 | 58.9 | 72.5 | ||

| B symptom | |||||

| Yes | 34 | 55.1 | 0.768 | 59.5 | 0.172 |

| No | 47 | 57.1 | 75.0 | ||

| LDH | |||||

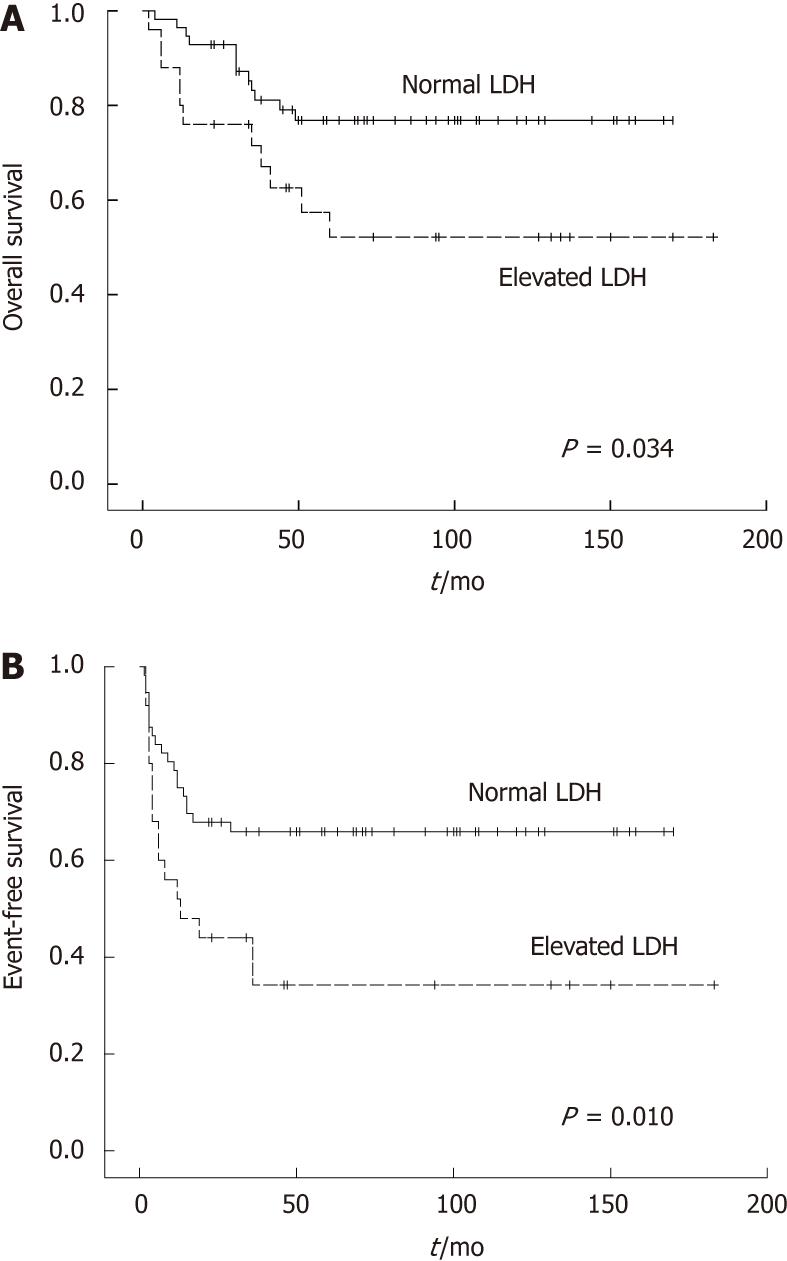

| Elevated | 25 | 34.2 | 0.010 | 52.2 | 0.034 |

| Normal | 56 | 65.9 | 76.9 | ||

| Treatment | |||||

| Surgery-based | 64 | 54.3 | 0.668 | 70.9 | 0.371 |

| Nonsurgical | 16 | 61.9 | 60.9 | ||

| Radical surgery | |||||

| Yes | 54 | 57.7 | 0.218 | 70.3 | 0.599 |

| No | 10 | 40.0 | 77.8 | ||

| Period | |||||

| A | 27 | 51.9 | 0.594 | 66.7 | 0.808 |

| B | 54 | 58.8 | 71.3 |

Female patients showed a better OS, but EFS did not different between two groups. The sites of origin were prognostic (Figure 1). EFS in different sites were significantly changed (P = 0.025), and OS in the small intestine and ileocaecal region were significantly longer compared with rectum and multiple sites (P = 0.016). Histologic subtype was prognostic for EFS and OS (P = 0.002 and P < 0.001, respectively). B cell phenotype had a better prognosis than T cell phenotype (Figure 2). Patients who had perforation showed a poorer EFS and OS than those did not perforate. In the normal lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) group, EFS and OS were significantly better compared with the elevated LDH group (P = 0.010 vs P = 0.034, respectively) (Figure 3).

We could not detect any significant influence of age, stage, bulky disease, B symptom, treatment or time trend in EFS and OS of the PIL.

Cox multivariate analysis revealed that small intestine and ileocaecal region localization, B-cell phenotype, and normal LDH were independent prognostic factors for better OS and EFS (Table 5).

| Variable | Overall survival | Event-free survival | ||

| Exp(B) | P value | Exp (B) | P value | |

| Pathology (B cell vs T cell) | 4.566 | 0.002 | 3.833 | 0.001 |

| LDH (normal 240 U/L) | 1.002 | 0.013 | 1.003 | 0.002 |

| Sites of origin | 1.370 | 0.052 | 1.442 | 0.010 |

| Gender | 2.980 | 0.089 | NE | |

| Perforation | 0.835 | 0.778 | 0.625 | 0.438 |

We also did prognostic analyses for the subgroups of B-cell lymphomas. Kaplan-Meier curves showed the survival of follicular lymphoma was better than MALT and DLBCL, and Burkitt lymphoma was the worst. However, the P values were not significant.

Cox multivariate analysis revealed that normal LDH were protective factors for better EFS (P = 0.007), and the gender and sites of origin were independent prognostic factors (P = 0.037 and P = 0.05, respectively). More specifically, females had better OS, and small intestine and ileocaecal region had better prognosis than rectum and multiple sites. We could not detect any significant influence of pathology, age, stage, bulky disease or treatment in B cell PIL (Table 6).

| Variable | Overall survival | Event-free survival | ||

| Exp(B) | P value | Exp (B) | P value | |

| Pathology (subtypes of B cell lymphoma) | 1.426 | 0.174 | 1.141 | 0.500 |

| LDH (normal 240 U/L) | 3.671 | 0.127 | 4.663 | 0.007 |

| Gender | 16.328 | 0.037 | 0.804 | 0.716 |

| Sites of origin | 1.604 | 0.050 | 1.306 | 0.151 |

Numbers of T-cell lymphoma were too small for sub-analyses. The small number of patients made it difficult to get an accurate analysis.

There are many publications about the epidemiology and clinical features of PIL. Only a few of the publications recruited more than 80 PIL patients[1,6,8], however, all of them were published before 2003. Except for a report on PGIL in Chinese patients which recruited 184 intestinal patients in 1995 from Hong Kong[13], there was no relative large-sample report from mainland China. Due to the differences in living habits and environment effects between Hong Kong and mainland China, it was necessary to analyze the epidemiology and prognosis of PIL in mainland China.

PIL is a male predominant disease, and male:female ratio was 2.5:1. In our series, we found that the age of the patients (median age = 46 and mean age = 46) were younger than the other reports[5,6,8,13-15].

The ileocaecal region was the most common site, with a frequency of 38.3%. Unlike the other reports[5,8,13,16], the colorectal involvement was more frequent. The rates of primary sites varied considerably in the other publications, especially noticeable for the rates of the ileocaecal region. The data ranged from 9.5%[16] to 38.3% in our report. We considered that the main reason for the difference was probably the precise definition of the ileocaecal region, which was missing in most reports. We believe it is important to distinguish it as a separate site, because our data show a significantly better prognosis for this region.

High-grade B cell lymphoma was the most common subtype in all the patients. This was followed by T cell lymphoma, which is apparently more than in Europe[5,6]. In our opinion, the reason for this is due to the higher ratio of T cell lymphoma in the NHL in China than European countries. Two publications reported T cell lymphoma only comprised 5% and 20.6% of the primary intestinal lymphoma in Chinese patients[17,18]. The difference between the reported series is difficult to interpret. Geographic variations in the prevalence of viral or bacterial infection, celiac disease, diet or other environmental factors may be the cause of the difference. However, the most likely reason may be due to these other studies having too small a sample size.

Our data confirmed the rising trend of PIL over the past 16 years in China, which was similar to reports from the United States[19] and Europe[6]. Furthermore, the number of patients with early stages or multiple sites has also increased. Advances in diagnostic procedures have led to an improvement in the accuracy in the diagnosis of lymphoma. However, an actual increase in the incidence of intestinal lymphoma should also be considered. Increasing exposure or susceptibility to risk factors, such as H. pylori infection, excessive protein or fat in the diet, and environmental pollution also may have contributed to this increase[6,20].

Most of the patients received combined treatment including surgery and chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy, 69.1% patients reached CR. The OS and EFS rates after 5 years were 71.6% and 60.9%, respectively. This was similar to the other reports[5,8].

Multivariate analysis revealed that small intestine and ileocaecal region localization, B-cell phenotype, and normal LDH were independent prognostic factors for better OS and EFS. Female gender[21] and no perforation indicated better OS in univariate analysis, but not significantly in multivariate analysis.

We also did prognostic analyses for the subgroups of B-cell lymphomas. The pathology subtypes of the B-cell lymphomas were not significant prognostic factors. Perhaps the small number of subtypes made it difficult to get an accurate analysis.

Stage and age were prognostic factors in many reports[2,22-25], and the size of the mass were also mentioned, but we found no find significant effect. Other factors reported to have contributed to survival included surgical resection and a good performance status[3].

We found surgery based treatment and radical surgery did not improve the survival rate. This fact raised the question of whether surgery is really necessary. Usually, the diagnostic difficulties, as well as the high rate of initial complications, led to primary resection of PIL in most patients. However, the efficacy of this procedure has not been evaluated so far. Furthermore, we observed complete remissions of PIL in patients receiving only conservative therapy[8,26,27].

It is clear that there was no benefit from lymph node clearance in lymphoma patients, which makes a case against extended surgical procedures. Surgery is still controversial as first-line therapy in patients with early stages of gastric lymphoma. Our findings indicate that patients with a clear diagnosis, better prognostic factors, and without initial complications should consider the conservative approach so that they may have a better quality of life. However, emergency operation is required when treatment related complications occur, such as perforation, ileus or bleeding.

PIL are heterogeneous diseases. In our point of view, the different prognostic factors and controversial treatment may be caused by the different constitution of these sub-types, ignoring racial and environment factors. Thus, further randomized prospective studies with a large number of patients are essential for this to be established.

We would like to thank Huang YH and Wong JL for technical help and Gao F who provided writing assistance.

In recent years, the incidence of primary extranodal lymphoma has increased, and gastrointestinal lymphomas are the most frequent subtype. However, the optimal treatment for primary intestinal lymphoma (PIL) remains controversial.

Numerous retrospective studies reported primary gastrointestinal lymphoma in Europe, but there were no large-sample studies from China. The optimal treatment for PIL remains controversial, and the prognostic data for patients with PIL remain to be elucidated.

This study analyzed the clinical feature, anatomic and histologic distribution, time trends, treatment responses and the prognosis of primary intestinal lymphoma in Chinese patients. The authors found surgery based treatment and radical surgery did not improve the survival rate. The fact raised the question of whether surgery is really necessary. The findings indicate that patients with a clear diagnosis, better prognostic factors, and without initial complications should consider the conservative approach, so that they may have a better quality of life.

Refined stratification of patients with PIL, according to the prognostic variables, may allow individualized treatment. Conservative treatment may be an optimal therapeutic modality for selected patients.

PIL: Primary intestinal lymphoma; marginal zone lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, enteropathy-type T cell lymphoma and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified et al are histologic types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

This is an interesting manuscript on primary gastrointestinal-lymphoma in China. The authors analyzed the clinicopathologic features of PIL with special reference to time trends. They determined the prognostic factors for intestinal lymphoma and evaluated the influence of therapeutic modalities on the prognosis. The results showed that conservative treatment might be an optimal therapeutic modality for selected patients with PIL.

Peer reviewer: Markus Raderer, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine I, Division of Oncology, Medical University Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna A-1090, Austria

S- Editor Wu X L- Editor Rutherford A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | d'Amore F, Brincker H, Grønbaek K, Thorling K, Pedersen M, Jensen MK, Andersen E, Pedersen NT, Mortensen LS. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a population-based analysis of incidence, geographic distribution, clinicopathologic presentation features, and prognosis. Danish Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1673-1684. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Aegerter P, Delmer A, Brousse N, Galian A, Rambaud JC. Primary digestive tract lymphoma: a prospective multicentric study of 91 patients. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Digestifs. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1662-1671. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Amer MH, el-Akkad S. Gastrointestinal lymphoma in adults: clinical features and management of 300 cases. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:846-858. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: II. Combined surgical and conservative or conservative management only in localized gastric lymphoma--results of the prospective German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3874-3883. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: I. Anatomic and histologic distribution, clinical features, and survival data of 371 patients registered in the German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3861-3873. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Gurney KA, Cartwright RA, Gilman EA. Descriptive epidemiology of gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a population-based registry. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1929-1934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mihaljevic B, Nedeljkov-Jancic R, Vujicic V, Antic D, Jankovic S, Colovic N. Primary extranodal lymphomas of gastrointestinal localizations: a single institution 5-yr experience. Med Oncol. 2006;23:225-35. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Iida M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma in Japan: a clinicopathologic analysis of 455 patients with special reference to its time trends. Cancer. 2003;97:2462-2473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lewin KJ, Ranchod M, Dorfman RF. Lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a study of 117 cases presenting with gastrointestinal disease. Cancer. 1978;42:693-707. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW. Pathology and genetics of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyons: IARC Press 2001; . |

| 11. | Musshoff K. [Clinical staging classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (author's transl)]. Strahlentherapie. 1977;153:218-221. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Mead GM, Sydes MR, Walewski J, Grigg A, Hatton CS, Pescosta N, Guarnaccia C, Lewis MS, McKendrick J, Stenning SP. An international evaluation of CODOX-M and CODOX-M alternating with IVAC in adult Burkitt's lymphoma: results of United Kingdom Lymphoma Group LY06 study. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1264-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liang R, Todd D, Chan TK, Chiu E, Lie A, Kwong YL, Choy D, Ho FC. Prognostic factors for primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 1995;13:153-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bairey O, Ruchlemer R, Shpilberg O. Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas of the colon. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8:832-835. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Wong MT, Eu KW. Primary colorectal lymphomas. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:586-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Morton JE, Leyland MJ, Vaughan Hudson G, Vaughan Hudson B, Anderson L, Bennett MH, MacLennan KA. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a review of 175 British National Lymphoma Investigation cases. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:776-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Li B, Shi YK, He XH, Zou SM, Zhou SY, Dong M, Yang JL, Liu P, Xue LY. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the small and large intestine: clinicopathological characteristics and management of 40 patients. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:375-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yin L, Chen CQ, Peng CH, Chen GM, Zhou HJ, Han BS, Li HW. Primary small-bowel non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a study of clinical features, pathology, management and prognosis. J Int Med Res. 2007;35:406-415. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Devesa SS, Fears T. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma time trends: United States and international data. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5432s-5440s. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Wright DH, Jones DB, Clark H, Mead GM, Hodges E, Howell WM. Is adult-onset coeliac disease due to a low-grade lymphoma of intraepithelial T lymphocytes? Lancet. 1991;337:1373-1374. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Aozasa K, Ueda T, Kurata A. Prognostic value of histologic and clinical factors in 56 patients with gastrointestinal lymphomas. Cancer. 1988;61:309-315. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Azab MB, Henry-Amar M, Rougier P, Bognel C, Theodore C, Carde P, Lasser P, Cosset JM, Caillou B, Droz JP. Prognostic factors in primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. A multivariate analysis, report of 106 cases, and review of the literature. Cancer. 1989;64:1208-1217. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Bellesi G, Alterini R, Messori A, Bosi A, Bernardi F, di Lollo S, Ferrini PR. Combined surgery and chemotherapy for the treatment of primary gastrointestinal intermediate- or high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Br J Cancer. 1989;60:244-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Salles G, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Berger F, Brousse N, Gisselbrecht C, Coiffier B. Aggressive primary gastrointestinal lymphomas: review of 91 patients treated with the LNH-84 regimen. A study of the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Agressifs. Am J Med. 1991;90:77-84. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Rackner VL, Thirlby RC, Ryan JA. Role of surgery in multimodality therapy for gastrointestinal lymphoma. Am J Surg. 1991;161:570-575. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Daum S, Ullrich R, Heise W, Dederke B, Foss HD, Stein H, Thiel E, Zeitz M, Riecken EO. Intestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a multicenter prospective clinical study from the German Study Group on Intestinal non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2740-2746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Egan LJ, Walsh SV, Stevens FM, Connolly CE, Egan EL, McCarthy CF. Celiac-associated lymphoma. A single institution experience of 30 cases in the combination chemotherapy era. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |