Published online Nov 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i41.4590

Revised: April 23, 2011

Accepted: April 30, 2011

Published online: November 7, 2011

AIM: To investigate the potential benefit of Fujinon intelligent chromo endoscopy (FICE)-assisted small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) for detection and characterization of small bowel lesions in patients with obscure gastroenterology bleeding (OGIB).

METHODS: The SBCE examinations (Pillcam SB2, Given Imaging Ltd) were retrospectively analyzed by two GI fellows (observers) with and without FICE enhancement. Randomization was such that a fellow did not assess the same examination with and without FICE enhancement. The senior consultant described findings as P0, P1 and P2 lesions (non-pathological, intermediate bleed potential, high bleed potential), which were considered as reference findings. Main outcome measurements: Inter-observer correlation was calculated using kappa statistics. Sensitivity and specificity for P2 lesions was calculated for FICE and white light SBCE.

RESULTS: In 60 patients, the intra-class kappa correlations between the observers and reference findings were 0.88 and 0.92 (P2), 0.61 and 0.79 (P1), for SBCE using FICE and white light, respectively. Overall 157 lesions were diagnosed using FICE as compared to 114 with white light SBCE (P = 0.15). For P2 lesions, the sensitivity was 94% vs 97% and specificity was 95% vs 96% for FICE and white light, respectively. Five (P2 lesions) out of 55 arterio-venous malformations could be better characterized by FICE as compared to white light SBCE. Significantly more P0 lesions were diagnosed when FICE was used as compared to white light (39 vs 8, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: FICE was not better than white light for diagnosing and characterizing significant lesions on SBCE for OGIB. FICE detected significantly more non-pathological lesions. Nevertheless, some vascular lesions could be more accurately characterized with FICE as compared to white light SBCE.

- Citation: Gupta T, Ibrahim M, Deviere J, Gossum AV. Evaluation of Fujinon intelligent chromo endoscopy-assisted capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastroenterology bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(41): 4590-4595

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i41/4590.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i41.4590

Obscure gastroenterology (GI) bleeding (OGIB) is defined as bleeding of unknown origin that persists or recurs after a negative initial or primary endoscopy (colonoscopy or upper endoscopy) result[1]. OGIB is frequently caused by a lesion in the small bowel[2]. Small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE), which allows the non-invasive visualization of mucosa throughout the entire small bowel, has revolutionized the exploration of small bowel diseases, and particularly the evaluation of OGIB[3]. Several studies showed that a SBCE is highly effective in detecting small-bowel lesions, with an overall diagnostic yield superior to that of push enteroscopy or radiological imaging, and comparable to double balloon enteroscopy (DBE)[4-7]. In addition, the SBCE procedure is technically easy and well tolerated, and carries a low risk of complications[6]. SBCE is the first-line examination in OGIB after a negative upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy[8].

The Fujinon intelligent chromo endoscopy (FICE) system is a new, virtual chromoendoscopy technique that enhances mucosal visibility, wherein the bandwidth of the conventional endoscopic image is narrowed down arithmetically using computerized spectral estimation technology[9]. Pohl et al[10,11] have previously demonstrated that FICE is comparable to conventional chromoendoscopy for surveillance of Barrett’s esophagitis and detection of colonic polyps. There are limited data regarding use of FICE for small bowel lesions. In a recent case series of 17 patients, Neumann et al[12] used DBE with FICE technology and demonstrated a benefit in characterizing angiodysplasias, in delineating the submucosal capillary network, and in the detection of small bowel polyps.

The positive yield of capsule endoscopy for evaluation of OGIB is around 60%. This value further decreases if the examination is delayed after the index bleed[6]. The addition of FICE technology to SBCE may improve the diagnostic yield.

The objective of our study was to assess the value of a FICE equipped small bowel (SB) capsule for evaluation of obscure GI bleeding and for the detection and characterization of SB lesions.

This study was conducted in the endoscopy unit of a tertiary care referral centre and teaching hospital. Sixty consecutive SBCE examinations (Pillcam SB2; Given Imaging Ltd, Israel), which were performed for OGIB, were chosen for the study. These examinations were performed to analyze either obscure-overt or obscure-occult GI bleeding in the preceding year. All included patients had received a polyethylene glycol-based bowel preparation before the examination and were given metoclopramide (10 mg) as a prokinetic before swallowing the capsule. These examinations were already analyzed under white light only by the senior consultant, who has more than eight years experience in conducting capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy. Two GI fellows with similar experience (70 procedures) in conducting capsule endoscopy (observers 1 and 2) analyzed the examinations with and without FICE enhancement using Rapid Reader (Version 6: Given Imaging Ltd, Israel); their experience was considered as reaching a minimum threshold number to assess competency. The fellows were allowed to use the speed of their choice for reading. Randomization was such that a fellow did not assess the same examination with and without FICE enhancement. In practice, fellow 1 read the videos 1 to 30 without FICE and the following videos (31 to 60) with FICE, and vice-versa for fellow 2. The entire examination was conducted either under white light or FICE technology. Rapid Reader (Version 6) provides three channels for FICE technology (Table 1)[13]. Channel 1 was used for examination with FICE by both fellows, as the wavelength settings for red, green and blue light were found to be most suited to small bowel evaluation. This was determined by the consultant and the observers after a pilot study of 15 patients. No historical data for the patients were made available to the observers. The analysis was conducted by the GI fellows on the department’s central computer. Individual findings were password protected. The boundary between the jejunum and the ileum was fixed empirically as the half time of the capsule small-bowel passage time. Both fellows used the common structured terminology as per the Given Capsule Endoscopy working group[14]. Both fellows were blinded to the findings (white light) of the senior consultant, which were taken as the reference. The senior consultant analyzed the results based on his reference findings. All findings were labeled as P0, P1 and P2 lesions (non-pathological, intermediate bleed potential-superficial erosions, red spots-or high potential bleed potential-hemorrhagic erosions, ulcer, arterio-venous malformations, or tumor) by the senior consultant[15]. Each time a lesion was seen in the FICE mode and not with white light, it was re-evaluated by the senior consultant. Comparison was performed for the detection of SB lesions, as well for characterization, i.e. vascular pattern, of a lesion that was considered as an arterio-venous malformation or a tumor as a Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) or an adenocarcinoma.

| Red | Green | Blue | |

| FICE channel 1 | 595 | 540 | 535 |

| FICE channel 2 | 420 | 520 | 530 |

| FICE channel 3 | 595 | 570 | 415 |

Institutional review board approval has been obtained from the local Ethical Committee for this retrospective study.

Inter-observer correlation was calculated by using kappa statistics. A kappa value of 1 was considered perfect agreement and 0 was considered no agreement at all. Sensitivity and specificity for P2 lesions was calculated for FICE and white light SBCE. SPSS software [version 16, (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL)] was used for the analysis. Statistical analysis of categorical values was conducted using the Fischer’s exact test. Significance was accepted at a value of P < 0 .05.

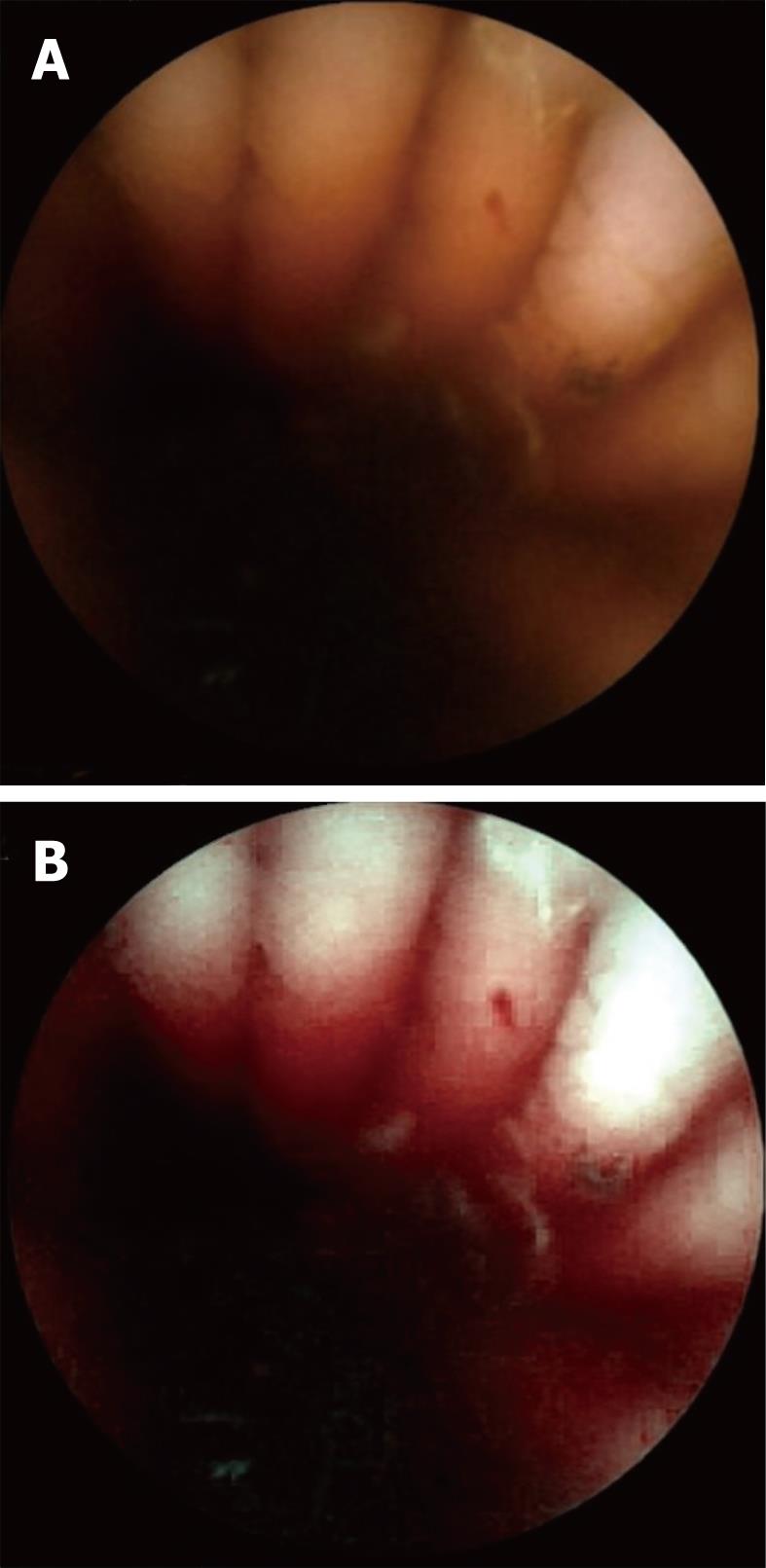

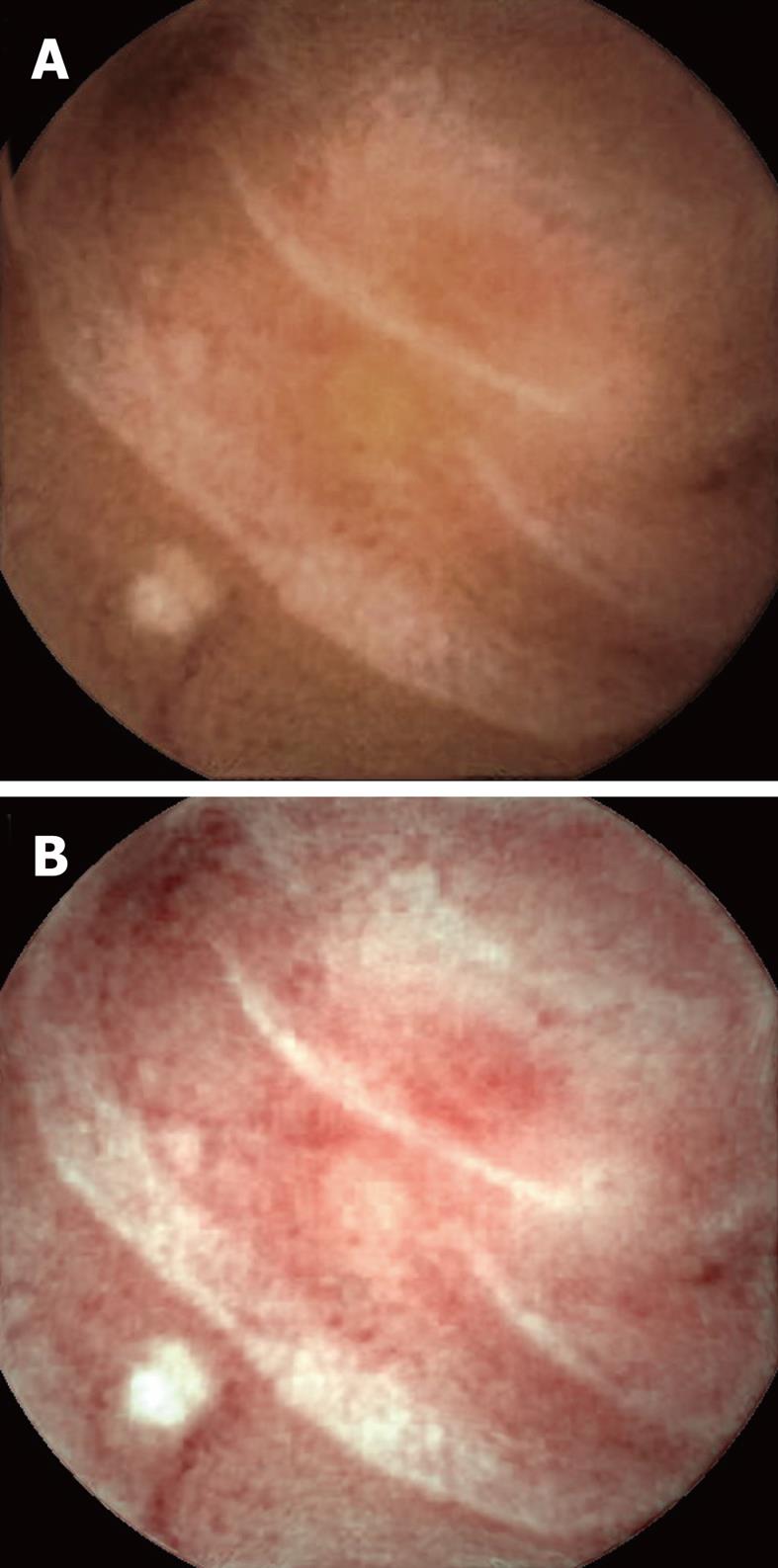

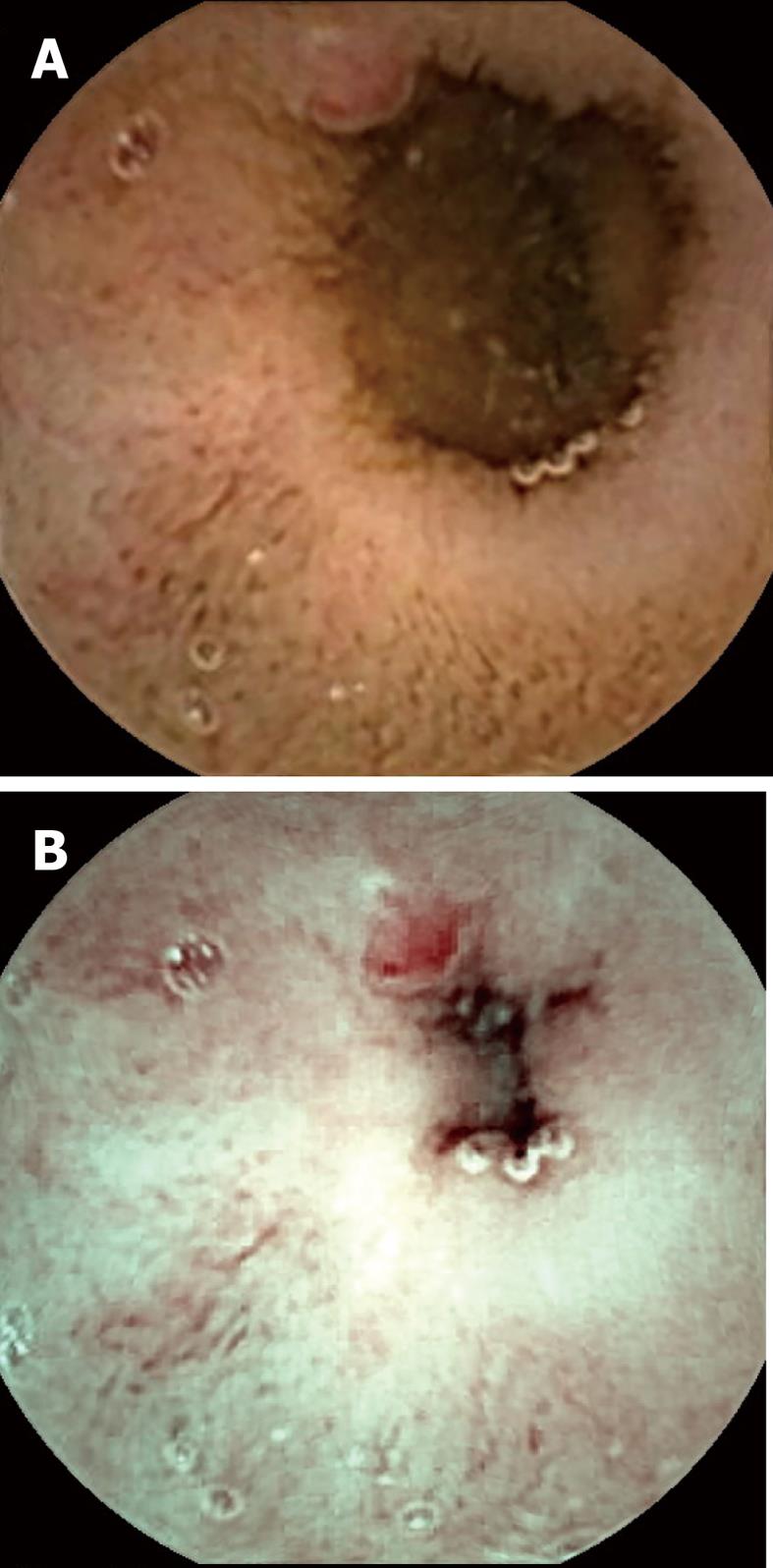

Visualization of the entire small bowel was achieved in 56 patients; in the remaining four, the capsule reached the terminal ileum. All patients had excellent bowel preparation. In these 60 patients, observers 1 & 2 detected 117 [P0 (20), P1 (37), P2 (60)] and 154 [P0 (27), P1 (55), P2 (72)] lesions, respectively, as compared to 131 [P0 (15), P1 (41), P2 (75)] by the senior consultant (Table 2). The commonest P2 lesions were arterio-venous malformations (n = 43), followed by small bowel ulcerations (n = 27), small bowel tumors (GIST n = 2; adenocarcinoma n = 1), and Dieulafoy’s lesions (n = 2). Intra-class correlation for P1 and P2 lesions was calculated as 0.69 and 0.89 respectively. Intra-class kappa correlations between the observers and reference findings were 0.88 (P2), 0.61 (P1) for SBCE using FICE, and 0.92 (P2), 0.79 (P1) for SBCE with white light respectively. Overall 153 lesions were diagnosed by the two observers with SBCE using FICE as compared to 118 by SBCE with white light (P = 0.15). Considering the senior consultant’s findings as the gold standard, for P2 lesions, the sensitivity was 94% (0.87-1.02) vs 97% (0.92-1.02) and specificity was 95% (0.87-1.03) vs 96% (0.86-1.04) for FICE and white light respectively. In 5/55 arterio-venous malformations, analysis of SBCE with FICE did not help in detection, but did result in better characterization of these P2 lesions as compared to analysis with white light (Figures 1-3). The mean duration for analyzing SBCE with FICE was longer than when white light was used (75 min vs 55 min). Significantly more P0 lesions were diagnosed by the 2 observers when FICE was used as compared to white light (39 vs 8, P < 0.01) (Table 3).

| Observer 1 | Observer 2 | Consultant (reference findings) | |

| Total | 117 | 154 | 131 |

| P0 | 20 | 27 | 15 |

| P1 | 37 | 55 | 41 |

| P2 | 60 | 72 | 75 |

| White light(two observers) | FICE(two observers) | P value(FICE vs WL for observers 1 and 2) | White light(senior consultant) | |

| P0 (no patients) | 8 (8) | 39 (24) | < 0.01 | 15 (10) |

| P1 (no patients) | 43 (33) | 49 (32) | 0.30 | 41 (29) |

| P2 (no patients) | 67 (38) | 65 (37) | 1.00 | 75 (40) |

Capsule endoscopy has become a cornerstone in the non-invasive evaluation of OGIB. The high diagnostic yield of intestinal SBCE has been proven in several studies, and ranges from 55% to 81%[4-7,16,17]. The rate of rebleeding in patients with OGIB and negative SBCE is significantly lower (4.6%) compared with those with a positive SBCE (48%)[18].

The FICE system is based on a computed spectral estimation technology that processes the reflected photons to reconstruct virtual images with a choice of different wavelengths. This leads to enhancement of the tissue microvasculature as a result of the differential optical absorption of light by hemoglobin in the mucosa. These abnormal areas can be defined by magnification[9,19,20].

Ours is the first study in the literature that has used the potential advantages of FICE to assist the detection and characterization of OGIB lesions by capsule endoscopy and using the new Rapid Reader 6 (Given Imaging Ltd, Israel). Our study suggests that addition of FICE technology does not help in identifying clinically significant lesions during analysis of SBCE. This contrasts with existing data on FICE. Ringold et al[21] described two cases in which high-contrast imaging with FICE improved the visibility of normal mucosal vessels and aided in the detection of vascular ectasias that were not easily seen by routine double-balloon enteroscopy. Similarly, improved detection rates for arterio-venous malformations and adenomatous polyps were noted by Neumann et al[12] with FICE aided enteroscopy in a series of 17 patients. Recently, Imagawa et al[22] reported that FICE may improve visibility of small bowel lesions that were detected under white light by video capsule. This series is not really comparable, in that 75 out of the 145 lesions were tumors. Moreover, the authors of the study did not report the detection rate or characterization of the lesions. Interestingly, they observed that setting 1 of the FICE system was the best one for improving visibility, confirming our selection of channel 1 as the most effective.

Arterio-venous malformations were also the predominant lesions in our study. Despite this, the number of lesions detected by FICE and white light capsule endoscopy were similar. In fact, FICE detected significantly more non-pathological (P0) lesions as compared to white light. There was similar concordance for FICE and white light SBCE for pathological lesions (P2) in our study. The mean duration for analyzing SBCE with FICE was longer than when white light was used, thus diminishing the appeal of FICE for SBCE.

There are a few reasons for the limited effectiveness of SBCE with FICE for identifying lesions in our study. All patients had excellent bowel preparation; hence, there was better visualization by white light alone. This is supported by a recent meta-analysis that showed that small-bowel purgative preparation (polyethylene glycol solution or sodium phosphate) improves the diagnostic yield of the examination[23]. We also found that white reflections tend to increase during the FICE mode, potentially interfering with the image quality. This may be particularly important for clearly discerning ulcerated lesions and may result in their erroneous reporting. In addition, channel 1 of FICE had a prominent red hue; hence, small red spots and prominent folds appeared as angio-ectasias when FICE was used. Several lymphangectasias, floating clots, and prominent veins were also found amongst the P0 lesions diagnosed by SBCE when FICE was used, thus reducing its utility.

We found that assessment of SBCE with FICE to be somewhat useful in the better characterization of vascular lesions. Arborization of the vascular network in the case of arterio-venous malformations was better assessed by FICE as compared to white light in 5 patients during this study, making their detection easier.

The strong points of the study were the use of the central workstation computer for capsule analysis, thereby enabling use of similar settings, image resolution and password protection of the reference and observers’ findings. The common structured terminology, as per the Given Capsule Endoscopy working group, was used by both observers[14].

A first limitation of our study was the analysis of retrospective data and the relatively small patient numbers. A longer prospective study with patient follow up may be required to confirm our findings.

A second limitation is the absence of a reference standard for defining the SB lesions. Obviously, in several patients, lesions were confirmed by enteroscopy, biopsies, radiology, or surgical specimens, but not for all. The absence of a well-defined standard reference is a common problem in studies assessing the diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy.

In conclusion, this is the first study to assess the ability of a FICE-equipped video capsule for detecting and characterizing SB lesions in cases of OGIB. SBCE with FICE technology did not improve diagnostic yield, but did detect more P0 lesions. FICE may improve the characterization of vascular lesions in a limited number of cases. Further improvements in software technology for FICE may be required to enhance its clinical application in capsule endoscopy for OGIB.

In our study, FICE-assisted SBCE analysis was not better than white light for diagnosing and characterizing significant lesions in the evaluation of OGIB. FICE detected significantly more non-pathological lesions; however, some vascular lesions could be more easily characterized on FICE as compared to white light SBCE.

Obscure gastroenterology bleeding (OGIB) is frequently caused by a lesion in the small bowel. Capsule endoscopy that allows visualization of the small bowel is now recognized as the first step procedure in case of OGIB. Arterio-venous malformations are the most frequent lesions that are responsible for OGIB. Quality of the video images, as well as the experience of the reader, are mandatory for providing accurate results.

The goals of video capsule endoscopy are the detection of lesions and their characterization. The reader is invited to qualify the lesion as clinically significant or not. This is important for defining further therapeutic strategy. Improvement of image quality may improve the diagnostic yield.

The Fujinon intelligent chromo endoscopy (FICE) system is a new, virtual chromoendoscopy technique that has been designed to enhance visibility of lesions. This technique, which is used for conventional endoscopy, has been adapted for video capsule endoscopy (given imaging). In this retrospective study, FICE did not improve the detection of small bowel lesions in comparison with the white light, but did allow better characterization of some vascular lesions.

FICE technology is now available in clinical practice. Its use should be reserved for the better characterization of lesions that were detected by white light. Some prospective studies should be performed for confirming the present data.

OGIB is defined as digestive bleeding of unknown origin that persists or recurs after a negative endoscopy work-up. Video capsule endoscopy is a non-invasive method allowing a complete investigation of the small bowel. FICE is a new chromoendoscopic tool that has been designed for enhancing visibility of lesions in comparison to white light.

This interesting study is well conducted and the results and conclusions are of practical application.

Peer reviewers: Roberto de Franchis, Professor of Medicine (Gastroenterology), Department of Medical Sciences, University of Milan, Head, Gastroenterology 3 Unit, IRCCS Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Mangiagalli and Regina Elena Foundation, Via Pace 9, 20122 Milano, Italy; Josep M Bordas, MD, Department of Gastroenterology IMD, Hospital Clinic, Llusanes 11-13 at, Barcelona 08022, Spain; John Marshall, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Missouri School of Medicine, Columbia, MO 65201, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Zuckerman GR, Prakash C, Askin MP, Lewis BS. AGA technical review on the evaluation and management of occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:201-221. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ell C, May A. Mid-gastrointestinal bleeding: capsule endoscopy and push-and-pull enteroscopy give rise to a new medical term. Endoscopy. 2006;38:73-75. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Pennazio M, Eisen G, Goldfarb N. ICCE consensus for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1046-1050. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Saurin JC, Delvaux M, Gaudin JL, Fassler I, Villarejo J, Vahedi K, Bitoun A, Canard JM, Souquet JC, Ponchon T. Diagnostic value of endoscopic capsule in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: blinded comparison with video push-enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:576-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Costamagna G, Shah SK, Riccioni ME, Foschia F, Mutignani M, Perri V, Vecchioli A, Brizi MG, Picciocchi A, Marano P. A prospective trial comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:999-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 517] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Delvaux M. Capsule endoscopy in 2005: facts and perspectives. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:23-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen X, Ran ZH, Tong JL. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with small bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4372-4378. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ladas SD, Triantafyllou K, Spada C, Riccioni ME, Rey JF, Niv Y, Delvaux M, de Franchis R, Costamagna G. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE): recommendations (2009) on clinical use of video capsule endoscopy to investigate small-bowel, esophageal and colonic diseases. Endoscopy. 2010;42:220-227. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Pohl J, May A, Rabenstein T, Pech O, Ell C. Computed virtual chromoendoscopy: a new tool for enhancing tissue surface structures. Endoscopy. 2007;39:80-83. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Pohl J, Nguyen-Tat M, Pech O, May A, Rabenstein T, Ell C. Computed virtual chromoendoscopy for classification of small colorectal lesions: a prospective comparative study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:562-569. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Pohl J, May A, Rabenstein T, Pech O, Nguyen-Tat M, Fissler-Eckhoff A, Ell C. Comparison of computed virtual chromoendoscopy and conventional chromoendoscopy with acetic acid for detection of neoplasia in Barrett's esophagus. Endoscopy. 2007;39:594-598. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Neumann H, Fry LC, Bellutti M, Malfertheiner P, Mönkemüller K. Double-balloon enteroscopy-assisted virtual chromoendoscopy for small-bowel disorders: a case series. Endoscopy. 2009;41:468-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pohl J, Aschmoneit I, Schuhmann S, Ell C. Computed image modification for enhancement of small-bowel surface structures at video capsule endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2010;42:490-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Korman LY, Delvaux M, Gay G, Hagenmuller F, Keuchel M, Friedman S, Weinstein M, Shetzline M, Cave D, de Franchis R. Capsule endoscopy structured terminology (CEST): proposal of a standardized and structured terminology for reporting capsule endoscopy procedures. Endoscopy. 2005;37:951-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | D'Halluin PN, Delvaux M, Lapalus MG, Sacher-Huvelin S, Ben Soussan E, Heyries L, Filoche B, Saurin JC, Gay G, Heresbach D. Does the "Suspected Blood Indicator" improve the detection of bleeding lesions by capsule endoscopy? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moreno C, Arvanitakis M, Devière J, Van Gossum A. Capsule endoscopy examination of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: evaluation of clinical impact. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2005;68:10-14. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini FP, De Franchis R. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:643-653. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Lai LH, Wong GL, Chow DK, Lau JY, Sung JJ, Leung WK. Long-term follow-up of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1224-1228. [PubMed] |

| 19. | DaCosta RS, Wilson BC, Marcon NE. Optical techniques for the endoscopic detection of dysplastic colonic lesions. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:70-79. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Wallace MB. Advances in endoscopic imaging of Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:699-700. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Rokkas T, Papaxoinis K, Triantafyllou K, Pistiolas D, Ladas SD. Does purgative preparation influence the diagnostic yield of small bowel video capsule endoscopy?: A meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:219-227. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Ringold DA, Sikka S, Banerjee B. High-contrast imaging (FICE) improves visualization of gastrointestinal vascular ectasias. Endoscopy. 2008;40 Suppl 2:E26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Imagawa H, Oka S, Tanaka S, Noda I, Higashiyama M, Sanomura Y, Shishido T, Yoshida S, Chayama K. Improved visibility of lesions of the small intestine via capsule endoscopy with computed virtual chromoendoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:299-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |