Published online Jan 28, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i4.534

Revised: July 20, 2010

Accepted: July 27, 2010

Published online: January 28, 2011

AIM: To present the experience and outcomes of the surgical treatment for the patients with anorectal melanoma from the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

METHODS: Medical records of the diagnosis, surgery, and follow-up of 56 patients with anorectal melanoma who underwent surgery between 1975 and 2008 were retrospectively reviewed. The factors predictive for the survival rate of these patients were identified using multivariate analysis.

RESULTS: The 5-year survival rate of the 56 patients with anorectal melanoma was 20%, 36 patients underwent abdominoperineal resection (APR) and 20 patients underwent wide local excision (WLE). The rates of local recurrence of the APR and WLE groups were 16.13% (5/36) and 68.75% (13/20), (P = 0.001), and the median survival time was 22 mo and 21 mo, respectively (P = 0.481). Univariate survival analysis demonstrated that the number of tumor and the depth of invasion had significant effects on the survival (P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis showed that the number of tumor [P = 0.017, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.273-11.075] and the depth of invasion (P = 0.015, 95% CI = 1.249-7.591) were independent prognostic factors influencing the survival rate.

CONCLUSION: Complete or R0 resection is the first choice of treatment for anorectal melanoma, prognosis is poor regardless of surgical approach, and early diagnosis is the key to improved survival rate for patients with anorectal melanoma.

- Citation: Che X, Zhao DB, Wu YK, Wang CF, Cai JQ, Shao YF, Zhao P. Anorectal malignant melanomas: Retrospective experience with surgical management. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(4): 534-539

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i4/534.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i4.534

Anorectal malignant melanoma (ARMM) is an infrequent fatal tumor. ARMM accounts for < 1% of anorectal malignant tumors and approximately 1%-2% of all melanomas[1]. Although there has been progress in the treatment of melanomas, the prognosis of ARMM is still very poor, and the 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) is 10% or less. In most cases, when patients are diagnosed with ARMM, local invasion or distal metastasis already exists[2], and because ARMM is not sensitive to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, selection of treatment methods is limited. At present, surgical treatment remains the main therapeutic method for ARMM, with abdominoperineal resection (APR) and wide local excision (WLE) as the most common approaches used. Nevertheless, there are controversies regarding which technique is superior in terms of long-term survival and overall quality of life. Because of the low incidence and poor biological behavior of ARMM, there has been no consensus about the therapeutic method for ARMM[3]. The current study involved a retrospective analysis of 56 patients with ARMM who underwent surgery in our hospital between 1975 and 2008. We compared the survival status of the patients after APR and WLE to determine the relationship between the surgical approaches and prognosis of ARMM. Cases with distal metastasis at the time of diagnosis were not included in this study.

Among the 56 patients, 22 were men and 34 were women; the ratio of males to females was 1:1.55. The mean age of the patients was 55 years (range, 36-81 years). The main symptoms were hematochezia in 32 cases, anal tumors in 11 cases, change in bowel habits in 6 cases, and bulge or pain in the anus in 7 cases. The distance from the tumor to the anal verge was < 5 cm in all the 56 patients, and < 3 cm in 47 (83.92%) patients. Misdiagnoses occurred in 32 (57.14%) cases. Thirteen cases were misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids, 8 cases as adenomas or polypus, 4 cases as cancer, and 1 case each as carcinoid, fibroma, malignant fibroma, eczema, and dysentery.

Routine pathologic examinations were carried out in all 56 cases and the diagnoses were made by two pathologists. There were 49 cases of pigmented melanomas, 7 cases of amelanotic melanomas, 50 cases of single lesions, 6 cases of multiple lesions. Ten cases had lesions invading into the mucosa, 6 cases into the submucosa, 19 cases into the muscle layer and 7 cases into the fibrous membrane, and the depth of lesion was not recorded in 14 cases. Among 36 patients undergoing APR, lymph node metastases occurred in 21 cases, while no lymph node metastases were noted in 14 cases, and the status of metastasis was not identified in 1 case. Immunohistochemical examinations were carried out for differential diagnosis in 28 cases.

Thirty-six cases underwent APR, 19 cases underwent WLE, 1 case underwent WLE+ lymph node dissection, Assisted radiotherapy was performed in 4 cases, and assisted biotherapy and chemotherapy were carried out in 19 cases. The main biological agent was interferon, and the main chemotherapeutic agents were dacarbazine and vincristine.

Postoperative follow-ups were made until December 2009 through outpatient visits, telephone interviews, and questionnaires, with a rate of 91% (51/56). The survival time was calculated from the day of surgery. SPSS13.0 software was used for statistical analyses. χ2 test was used to ascertain the relationship between the clinical pathologic parameters and local recurrence. The Kaplan-Meier method and long-rank univariate analysis were used for calculating the survival rates and multivariate analysis was conducted for the COX model.

All 56 cases underwent tumorectomy. The local recurrence rate was 32.14% (18/56) and the rate of metastasis was 58.92% (33/56). Thirty-six cases underwent APR, with a local recurrence rate of 16.13% (5/36). Twenty cases underwent WLE, with a local recurrence rate of 68.75% (13/20). The results of the χ2 test showed that there was a correlation between the surgical method and local recurrence (P = 0.001).

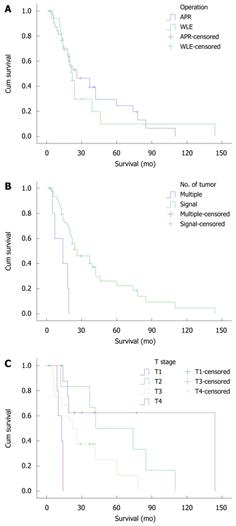

The 5-year overall survival rate for all the patients was 20%. The 5-year overall survival rate was 24.6% in the APR group and 9.9% in the WLE group. The median survival time was 22 mo in the APR group and 21 mo in the WLE group (P = 0.645, Figure 1A).

In this study, the mean follow-up period was 4-144 mo, the median survival time was 21 mo, and the 5-year overall survival rate was 20%. Based on univariate analysis, the factors correlated with prognosis were the number of tumors and the depth of invasion (Table 1). When these factors were subjected to a Cox model with stepwise regression, the results showed that the number of tumors [P = 0.017, OR = 3.755, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.273-11.075 (Figure 1B)] and the depth of invasion [P = 0.015, OR = 3.079, 95% CI = 1.249-7.591 (Figure 1C)] were the most important influencing factors for prognosis.

| Factors | Cases | 5-yr survival (%) | P value |

| Gender | 0.759 | ||

| Male | 22 | 23.4 | |

| Female | 34 | 18.1 | |

| Age (yr) | 0.524 | ||

| ≤ 45 | 14 | 16.7 | |

| > 45 | 42 | 21.1 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.815 | ||

| ≤ 2 | 17 | 19.9 | |

| > 2 | 29 | 22.2 | |

| Lesion | 0.001 | ||

| Single | 50 | 22.4 | |

| Multiple | 6 | 0.0 | |

| Pigment | 0.245 | ||

| Yes | 43 | 17.4 | |

| No | 4 | 33.33 | |

| Depth of invasion | 0.002 | ||

| T1 | 10 | 62.5 | |

| T2 | 6 | 50.0 | |

| T3 | 19 | 12.5 | |

| T4 | 7 | 0.0 | |

| Lymph metastasis | 0.275 | ||

| Yes | 21 | 20.6 | |

| No | 15 | 30.0 | |

| Surgical method | 0.645 | ||

| Abdominoperineal resection | 36 | 24.6 | |

| Local excision | 20 | 9.9 | |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 0.256 | ||

| Yes | 19 | 17.8 | |

| No | 15 | 0.0 |

ARMM is an infrequent fatal tumor and accounts for 1%-2% of all melanomas. The rectum and the anal canal are the most common organs for ARMM onset, except the skin and eyes. In this study, the clinical characteristics of ARMM included: an age of onset of 55 years, hematochezia as the most common primary symptom, similar incidences of the tumor in the rectum and anal canal, more females than males affected, and a ratio of males to females of 1:1.6, which is consistent with a previous report[4]. Although the gastrointestinal tract contains melanocytes, ARMM is most likely located around the anocutaneous line, including the anocutaneous line and the anal canal. In our study, the distance from the tumor to the anal verge was < 5 cm in all 47 cases; < 3 cm in 43 (91.5%) cases; and < 2 cm in 16 cases. Zhang et al[4] summarized 216 cases of ARMM, carried out a descriptive analysis of the characteristics of tumor growth, and found that ARMM was more likely benign. For example, the maximum diameter of the tumor was relatively small; 43.6% were polypoid type in gross morphology, and only 23.6% of the tumors were invading the surrounding tissues and fixed. Although most tumors have hard surfaces and ulcers on the surface, there are tumors with soft and smooth surfaces. Melanin has been reported under light microscope in 70%-80% of tumors; however, the percentage was 91% in the current study.

Misdiagnosis is a significant characteristic of ARMM. Because ARMM is rare and its clinical features lack specificity, the rate of misdiagnosis is high. In this study the rate of misdiagnosis was 57.14% (32/56), which is similar to Zhang’s report[5]. The early symptoms of ARMM resemble some anorectal benign diseases, such as thrombosed hemorrhoids, mixed hemorrhoids, and rectal adenomas. In the advanced stage, ARMM is similar to rectal cancer. Amelanotic ARMM is more likely to be misdiagnosed. The causes of misdiagnosis are as follows: (1) physicians do not have sufficient knowledge about this disease; (2) the clinical features lack specificity; and (3) the pathologic diagnosis is difficult; in particular, immunohistochemical methods are needed for a correct diagnosis of amelanotic melanomas. The data of this study suggest that the prognosis for ARMM is better when the tumor is limited in the mucosa and submucosa, and in such cases the tumor can be treated by WLE, therefore, lowering the misdiagnosis rate is very important for early treatment. There are several methods that can help improve the diagnosis of ARMM. (1) Rectal examination and endoscopy: ARMM is most likely located in the anocutaneous line and the anal canal. In this study, the distance from the tumor to the anal verge was < 5 cm in all cases, therefore, the rectal examination and the endoscopy are very important. Most patients with such melanomas complained of bleeding, pain, or an anal mass. Digital examination provides information concerning size, fixation and ulceration of the tumor, and proctosigmoidoscopy may be suggestive of anorectal melanoma[6]. When the pathologic examination is performed in patients with suspected ARMM, the whole tumor should be resected to prevent iatrogenic dissemination; (2) Light microscopy: Light microscopy can localize pigment granules in the cytoplasm of tumor cells in most cases. If the existence of pigment granules is not clear, other methods, such as Fontana-Masson-stained sections for melanin, dopamine staining, or enzyme reactions, can be used to confirm the diagnosis; and (3) Immunohistochemical staining: Because the aforementioned methods can not diagnose amelanotic ARMM, the immunohistochemical method combining HMB45, S-100 protein, and the vimentin test can be used[7].

The malignancy of ARMM is high. The 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) is < 10% and the mean survival time is 12-18 mo[8,9]. ARMM is not sensitive to radiotherapy or chemotherapy; surgical excision remains the most important therapy. APR and WLE are the most common surgical methods used; however, since the tumor is located in the anorectal area, there have been differences in the viewpoint regarding which surgical method is most suitable for long-term survival and overall life quality[10]. At present, the results of most studies have indicated no difference between the two surgical methods with respect to the survival rate. Yeh et al[11] performed a retrospective analysis of 46 patients with ARMM who were treated surgically; among them, 19 patients underwent APR and 26 patients underwent WLE. The rates of local recurrence were 21% and 26%, respectively, and there were no statistical differences. The DSS was 34% and 35%, respectively. The neural invasion around the tumor was the only independent prognosis factor (P = 0.01). It was considered that the range of surgical excision was not correlated with the prognosis. Because WLE has significant advantages, such as minor surgical trauma, quick recovery, less effect on the function of the intestinal tract, and preservation of anal function, it was suggested that WLE should be the first choice for treatment of ARMM. Another point of view considered that APR has a certain advantage in the control of local recurrences, thus it should be the first choice for patients with early-stage disease.

Because of the infrequency of ARMM, it is difficult to carry out a prospective, randomized, controlled study, and there have been only some retrospective data of small samples studied. Thibault et al[12] summarized 24 references involving 428 cases of AMM patients who underwent APR and WLE. There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to the 5-year DSS. A series of 26 patients from the MD Anderson Cancer Center reported fewer local recurrences after APR (29%) than after wide local excision (58%), but these authors noted that the majority of recurrences occurred in patients who also had regional or systemic metastases and that local recurrence did not affect survival[13]. In our series, the 5-year overall survival rate was 24.6% in the APR group and 9.9% in the WLE group (P = 0.645). The rate of local recurrence was lower in the APR group than in the WLE group (16.13% and 68.75%, respectively, P = 0.001). It is suggested that APR can decrease local recurrence, but no significant difference between the two groups with respect to the 5-year overall survival rate.

The definition of relevant pathological prognostic parameters which might be able to guide the clinical decision is also lacking in anorectal melanomas. Tumor thickness less than 2 mm has been advocated as a good prognostic factor by Roumen in his study[14]. Weyandt et al[15] reported that, in early-stage disease with a tumor thickness below 1 mm, a local sphincter saving excision with a 1-cm safety margin would be appropriate. In the cases of a tumor thickness between 1 and 4 mm, a local sphincter saving excision with a safety margin of 2 cm seems to be adequate. In this study, multivariate analysis showed that a single lesion and the depth of tumor invasion were the most important factor influencing prognosis. Therefore, early diagnosis is the key to improved survival rate for patients with anorectal melanoma[16].

In this study, the surgical method affected the rate of local recurrence, but it did not affect the prognosis of ARMM, confirming that the quick development of a tumor over the body obscures the effect of surgical method on the control of a local tumor. Hence, as with other malignant tumors, the metastatic capability of ARMM was determined at the moment of tumorigenesis, and it is independent from other factors, such as the size of tumor and metastasis to the lymph nodes[17]. ARMM is a systemic disease and its prognosis is not affected by the surgical method, so that the goal of surgical therapy is to improve the quality of life of those patients maximally, by now, most scholars hold the same view[18].

Because ARMM is highly invasive and the blood supply to the area of the anocutaneous line is abundant, lymph node and distal metastases may occur. Therefore, biotherapy and chemotherapy are necessary as postoperative adjunctive therapies. The rate of complete remission is 11% when metastatic ARMM is treated by chemotherapy and biotherapy[19]. Cytotoxic chemotherapeutics (cisplatin, catharanthine, or dacarbazine), combined with immunomodulators (interleukin-2 and interleukin-α) can improve the survival status of some patients. Ballo et al[20] reported postoperative radiotherapy in a retrospective analysis of 23 patients with AM who were managed with sphincter-sparing procedures and adjuvant radiotherapy. Although the overall survival was not improved, the actuarial 5-year local and nodal control was 74% and 87%, respectively. This degree of locoregional control is superior to the standard WLE alone, in which local control is typically poor (a crude estimate of 35%). This study did not investigate the effects of adjuvant chemotherapy and postoperative radiotherapy on the prognosis, which is also a controversial topic. Further studies are needed to demonstrate the benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy and postoperative radiotherapy.

It can be concluded that the surgical method does not affect the prognosis of ARMM. If the tumor can be resected totally, WLE should be the first choice of treatment. APR can be performed as a rescue therapy when WLE is impossible, the margins of the local excision are positive, or in the event of recurrence[21].

Endorectal ultrasonography is increasingly employed in the preoperative staging of rectal cancers. Accuracy in evaluating tumor depth ranges from 81% to 94%, and accuracy in detecting lymph node metastases ranges from 58% to 80%[22], and preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often of great importance when planning rectal cancer surgery[23]. Use of endoanal ultrasonography and MRI for preoperative staging of patients with anorectal melanoma has rarely been reported. In this study, no patient underwent preoperative ultrasonographic and MRI evaluation, but some patients are being followed postoperatively in an attempt to detect early recurrence. We are currently evaluating the accuracy of endoanal ultrasonography and MRI in the preoperative assessment of melanoma as well as other anal canal malignancies.

This study was hampered by several limitations. First, it is retrospective, based mainly on data from medical documentation. Second, data are incomplete. In some patients, medical documentation was absent, and follow-up data were missing. Finally, patients received heterogeneous treatment and no prospective protocol was followed. Therefore, planning of surgery after thorough clinical and radiological investigations, including MRI of the pelvis and endoluminal ultrasound for tumor depth, may aid in defining the appropriate surgical approach for anorectal melanoma.

Anorectal malignant melanoma (ARMM) is an infrequent fatal tumor. ARMM represents < 1% of anorectal malignant tumors and approximately 1%-2% of all melanomas. Although there has been progress in the treatment of melanomas, the prognosis of ARMM is still very poor, and the 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) is 10% or less. At present, surgical therapy remains the main treatment method for ARMM, with abdominoperineal resection (APR) and wide local excision (WLE) as the most common methods used. Nevertheless, there are considerable controversies regarding which technique is superior in terms of long-term survival and overall quality of life. Because of the low incidence and poor biological behavior of ARMM, there has been no consensus reached about the treatment method for ARMM.

The authors compared the survival status of the patients after APR and WLE to determine the relationship between the surgical approaches and prognosis of ARMM, and found that complete or R0 resection is the first choice of treatment for anorectal melanoma, prognosis is poor regardless of surgical approach, and early diagnosis is the key to improved survival rate for patients with anorectal melanoma.

It can be concluded that the surgical method does not affect the prognosis of ARMM. If the tumor can be resected totally, WLE should be the first choice of treatment. APR can be performed as a rescue therapy when WLE is impossible, the margins of the local excision are positive, or in the event of recurrence.

Planning of surgery after thorough clinical and radiological investigations, including MRI of the pelvis and endoluminal ultrasound for tumor depth, may aid in defining the appropriate surgical approach for anorectal melanoma.

ARMM is an infrequent fatal tumor. At present, surgical therapy remains the main treatment method for ARMM, with APR and WLE as the most common methods used. If the tumor can be resected totally, WLE should be the first choice of treatment. APR can be performed as a rescue therapy when WLE is impossible, the margins of the local excision are positive, or in the event of recurrence.

The authors should address how the decision was made as to which of the treatments was recommended to the patients. This may very well have influenced the results in local recurrence.

Peer reviewers: Philip H Gordon, Professor, Department of Surgery, McGill University, 3755 Cote Ste. Catherine Road, Suite G-314, Montreal, Quebec, H3T 1E2, Canada; Jai Dev Wig, MS, FRCS, Former Professor and Head, Department of General Surgery, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh 160012, India

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Pack GT, Oropeza R. A comparative study of melanoma and epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal: A review of 20 melanomas and 29 epidermoid carcinomas (1930 to 1965). Dis Colon Rectum. 1967;10:161-176. |

| 2. | Chiu YS, Unni KK, Beart RW Jr. Malignant melanoma of the anorectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1980;23:122-124. |

| 3. | Malik A, Hull TL, Floruta C. What is the best surgical treatment for anorectal melanoma? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:121-123. |

| 4. | Zhang S, Gao F, Chen LS, Tang ZJ, Liang JL, Wu Q. [Clinical analysis of anorectal malignant melanoma]. Zhonghua Weichang Waike Zazhi. 2005;8:309-311. |

| 5. | Zhang S, Gao F, Wan D. Effect of misdiagnosis on the prognosis of anorectal malignant melanoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136:1401-1405. |

| 6. | Stoidis CN, Spyropoulos BG, Misiakos EP, Fountzilas CK, Paraskeva PP, Fotiadis CI. Diffuse anorectal melanoma; review of the current diagnostic and treatment aspects based on a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:64. |

| 7. | Chute DJ, Cousar JB, Mills SE. Anorectal malignant melanoma: morphologic and immunohistochemical features. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126:93-100. |

| 9. | Brady MS, Kavolius JP, Quan SH. Anorectal melanoma. A 64-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:146-151. |

| 10. | Ishizone S, Koide N, Karasawa F, Akita N, Muranaka F, Uhara H, Miyagawa S. Surgical treatment for anorectal malignant melanoma: report of five cases and review of 79 Japanese cases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1257-1262. |

| 11. | Yeh JJ, Shia J, Hwu WJ, Busam KJ, Paty PB, Guillem JG, Coit DG, Wong WD, Weiser MR. The role of abdominoperineal resection as surgical therapy for anorectal melanoma. Ann Surg. 2006;244:1012-1017. |

| 12. | Thibault C, Sagar P, Nivatvongs S, Ilstrup DM, Wolff BG. Anorectal melanoma--an incurable disease? Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:661-668. |

| 13. | Ross M, Pezzi C, Pezzi T, Meurer D, Hickey R, Balch C. Patterns of failure in anorectal melanoma. A guide to surgical therapy. Arch Surg. 1990;125:313-316. |

| 14. | Roumen RM. Anorectal melanoma in The Netherlands: a report of 63 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1996;22:598-601. |

| 15. | Weyandt GH, Eggert AO, Houf M, Raulf F, Bröcker EB, Becker JC. Anorectal melanoma: surgical management guidelines according to tumour thickness. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:2019-2022. |

| 16. | Hillenbrand A, Barth TF, Henne-Bruns D, Formentini A. Anorectal amelanotic melanoma. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:612-615. |

| 18. | Iddings DM, Fleisig AJ, Chen SL, Faries MB, Morton DL. Practice patterns and outcomes for anorectal melanoma in the USA, reviewing three decades of treatment: is more extensive surgical resection beneficial in all patients? Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:40-44. |

| 19. | Kim KB, Sanguino AM, Hodges C, Papadopoulos NE, Eton O, Camacho LH, Broemeling LD, Johnson MM, Ballo MT, Ross MI. Biochemotherapy in patients with metastatic anorectal mucosal melanoma. Cancer. 2004;100:1478-1483. |

| 20. | Ballo MT, Gershenwald JE, Zagars GK, Lee JE, Mansfield PF, Strom EA, Bedikian AY, Kim KB, Papadopoulos NE, Prieto VG. Sphincter-sparing local excision and adjuvant radiation for anal-rectal melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4555-4558. |

| 21. | Belli F, Gallino GF, Lo Vullo S, Mariani L, Poiasina E, Leo E. Melanoma of the anorectal region: the experience of the National Cancer Institute of Milano. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:757-762. |

| 22. | Phang PT, Wong WD. The use of endoluminal ultrasound for malignant and benign anorectal diseases. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 1997;13:47-53. |

| 23. | Daniels IR, Fisher SE, Heald RJ, Moran BJ. Accurate staging, selective preoperative therapy and optimal surgery improves outcome in rectal cancer: a review of the recent evidence. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:290-301. |