Published online Jan 28, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i4.522

Revised: September 27, 2010

Accepted: October 3, 2010

Published online: January 28, 2011

AIM: To investigate the accuracy of T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI T2*) in the evaluation of iron overload in beta-thalassemia major patients.

METHODS: In this cross-sectional study, 210 patients with beta-thalassemia major having regular blood transfusions were consecutively enrolled. Serum ferritin levels were measured, and all patients underwent MRI T2* of the liver. Liver biopsy was performed in 53 patients at an interval of no longer than 3 mo after the MRIT2* in each patient. The amount of iron was assessed in both MRI T2* and liver biopsy specimens of each patient.

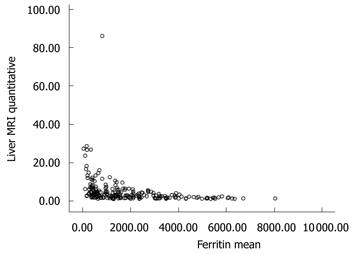

RESULTS: Patients’ ages ranged from 8 to 54 years with a mean of 24.59 ± 8.5 years. Mean serum ferritin level was 1906 ± 1644 ng/mL. Liver biopsy showed a moderate negative correlation with liver MRI T2* (r = -0.573, P = 0.000) and a low positive correlation with ferritin level (r = 0.350, P = 0.001). Serum ferritin levels showed a moderate negative correlation with liver MRI T2* values (r = -0.586, P = 0.000).

CONCLUSION: Our study suggests that MRI T2* is a non-invasive, safe and reliable method for detecting iron load in patients with iron overload.

- Citation: Zamani F, Razmjou S, Akhlaghpoor S, Eslami SM, Azarkeivan A, Amiri A. T2* magnetic resonance imaging of the liver in thalassemic patients in Iran. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(4): 522-525

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i4/522.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i4.522

Conventional treatment of beta-thalassemia major requires regular blood transfusions to maintain pre-transfusion hemoglobin level above 90 g/L[1]. A major drawback of this treatment is transfusion siderosis, which, in association with the increased intestinal iron absorption, apoptosis of the erythroid precursors and peripheral hemolysis, leads to inexorable iron accumulation in various organs such as the heart, liver and endocrine organs[2]. The assessment of body iron is still dependent upon indirect measurements, such as levels of serum ferritin, as well as direct measurements of the liver iron content[3]. Serum ferritin has been widely used as a surrogate marker but it represents only 1% of the total iron pool, and as an acute phase protein, it is not specific because the levels can be raised in inflammation (e.g. hepatitis) and liver damage[4]. Liver iron concentration measured by needle biopsy is the gold standard for evaluation of siderosis. However, it is an invasive technique which is not easily repeated and its accuracy is greatly affected by hepatic inflammation-fibrosis and uneven iron distribution[4]. More recently, biomagnetic susceptometry and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been validated for measuring iron overload, and these techniques have great merit in being noninvasive[5]. Biomagnetic susceptometry is a non-invasive, well calibrated and validated method as a quantitative measurement technique, but it has limited clinical value because of its high cost and technical demands[6]. MRI has been considered a potential method for assessing tissue iron overload, as iron accumulation in various organs causes a significant reduction in signal intensity stemming from a decrease in the T2 relaxation time[7,8].

The objective of the present study was to report our experience of the MRI technique in assessing hepatic iron overload in thalassemic patients.

Between January 2008 and April 2009, 210 patients with beta-thalassemia major (114 females, 96 males) referred to the thalassemia clinic of Firuzgar Hospital were consecutively enrolled in this cross-sectional study. Ages ranged from 8 to 54 years with a mean of 24.59 ± 8.5 years.

Patients were treated conventionally with regular blood transfusion, in order to maintain the pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration above 90 g/L. Regarding chelation therapy, all patients were receiving deferoxamine at a dose of 40 mg/kg, 5-7 times per week, by 8-hourly subcutaneous infusion.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences and written informed consent was obtained from all patients for the procedures studied.

A 5 mL blood sample was obtained from each patient for routine laboratory tests and measurement of ferritin level. Serum ferritin concentrations were assayed in all patients before the MRI scan, using an enzyme-linked radioimmunoassay method (Monobind Kit, USA).

Liver biopsy was performed with a 16-gauge Tru-Cut needle (TSK Laboratory, Japan) in 53 patients who gave written informed consent to undergo the biopsy for this study. Each specimen was at least 2 cm in length. The specimens were kept in 10% formaldehyde solution, and were sent to the Department of Pathology of Firuzgar Hospital. The specimens were stained with hematoxylin & eosin and viewed by an expert pathologist. The amount of stainable iron was graded 0-4 according to the Scheuer et al[9] method.

It is notable that the interval between liver biopsy and MRI of the liver and heart was less than 3 mo in all patients.

MRI scans were performed using a 1.5 Tesla Magnetom Siemens Symphony scanner (Siemens Medical Solution, Erlangen, Germany). Each scan lasted about 10-15 min and included the measurement of hepatic and myocardial T2* quantities. A standard quadrature radiofrequency body coil was used in all measurements for both excitation and signal detection. Respiratory triggering was used to monitor the patients’ breathing. Cardiac electrocardiographic gating was used. Spatial presaturation slabs were used to suppress motion-related artifacts.

The MRI T2* of the liver was determined using a single 10 mm slice through the center of the liver scanned at 12 different echo times (TE 1.3-23 ms). Each image was acquired during an 11-13 s breathhold using a gradient-echo sequence (repetition time 200 ms, flip angle 20°, base resolution matrix 128 pixels, field of view 39.7 cm × 19.7 cm, sampling bandwidth 125 kHz).

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 15 for Windows™ (SPSS® Inc., Chicago, IL). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD and count (percent) for categorical variables. The relationship between continuous variables was evaluated by the Pearson correlation coefficient for normally distributed data and Spearman’s Rank correlation coefficient for non-normally distributed data. All tests of significance were two-tailed and considered to be significant at P < 0.05.

All patients underwent MRI and 53 patients had a liver biopsy. The mean serum ferritin level of all patients was 1906 ± 1644 ng/mL. Serum ferritin levels showed a moderate negative correlation with liver T2* MRI values (r = -0.586, P = 0.000) (Figure 1). Of the 53 patients who had a liver biopsy, 5 patients had grade I liver siderosis, 19 had grade II, 17 had grade III and 12 had grade IV liver siderosis. The degree of siderosis assessed by liver biopsy showed a moderate negative correlation with liver T2* MRI (r = -0.573, P = 0.000) and a low positive correlation with ferritin level (r = 0.350, P = 0.001).

It is evident that different non-invasive methodologies have been implemented for the detection of organ-specific iron burden in patients with thalassemia major. Among these, MR relaxometry has the potential to become the method of choice for non-invasive, safe and accurate assessment of organ-specific iron load[10]. Until recently serum ferritin levels and liver biopsy have been the most commonly used methods for estimating body iron stores in the thalassemic population. However, ferritin levels are not fully acceptable because there have been significant variations due to inflammation, infections and chronic disorders[3].

We found a moderate correlation (r = -0.59, P < 0.001) between serum ferritin levels and hepatic T2* levels. These findings are compatible with other reported studies with highest correlation[3,11,12]. Attempts to correlate serum ferritin levels and hepatic iron concentrations have failed to demonstrate a linear relationship between the two parameters[11].

Liver biopsy has been regarded as the most precise method to measure body iron content if direct measurement of the iron concentration was applied. However, this is an invasive procedure which is not available in most clinical settings.

Our results revealed no reasonable correlation between histological grade of siderosis (HGS) and serum ferritin. However, a moderate correlation with liver T2* (r = 0.57, P < 0.001) indicated that HGS could still be considered as a method of evaluating thalassemic patients. Liver iron concentration showed significant correlation with hepatic T2* (r > 0.9). These results indicated that MRI T2* measurement is of more value than HGS in thalassemic patients.

The most important limitation of our study was the lack of a consideration of intervening factors that may affect the serum ferritin levels such as C-reactive protein, white blood cell count and liver function tests.

In conclusion, although hepatic iron content and serum ferritin levels have been considered as the gold standards in evaluating body iron load for several years, iron accumulation in different organs proceeds independently. This emphasizes the importance of direct iron load measurement in each involved organ and direct evaluation of the efficacy of different therapeutic measures.

According to our study, the serum ferritin level is not a reliable method for estimating the level of iron overload in thalassemic patients. MRI T2* is a more accurate and non-invasive method which we recommend for measurement of iron load in these patients.

Iron overload is a common and serious problem in thalassemic major patients. As iron accumulation is toxic in the body’s tissues, accurate estimation of iron stores is of great importance in these patients to prevent iron overload by an appropriate iron chelating therapy.

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for evaluating iron stores but it is an invasive method which is not easily repeatable in patients. Introduction of other more applicable methods seems to be necessary.

The authors found that MRI T2 * might be an accurate method for estimation of whole body iron.

According the findings, the authors suggest that clinicians consider MRI as an accurate method to evaluate the iron overload in patients with thalassemia major.

This is an interesting report.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Paul Sharp, BSc (Hons), PhD, Nutritional Sciences Division, King’s College London, Franklin Wilkins Building, 150 Stamford Street, London, SE1 9NH.

United Kingdom

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Christoforidis A, Haritandi A, Tsitouridis I, Tsatra I, Tsantali H, Karyda S, Dimitriadis AS, Athanassiou-Metaxa M. Correlative study of iron accumulation in liver, myocardium, and pituitary assessed with MRI in young thalassemic patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;28:311-315. |

| 2. | Rund D, Rachmilewitz E. Beta-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1135-1146. |

| 3. | Voskaridou E, Douskou M, Terpos E, Papassotiriou I, Stamoulakatou A, Ourailidis A, Loutradi A, Loukopoulos D. Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of iron overload in patients with beta thalassaemia and sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:736-742. |

| 4. | Argyropoulou MI, Astrakas L. MRI evaluation of tissue iron burden in patients with beta-thalassaemia major. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:1191-1200; quiz 1308-1309. |

| 5. | Pennell DJ. T2* magnetic resonance and myocardial iron in thalassemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1054:373-378. |

| 6. | Perifanis V, Economou M, Christoforides A, Koussi A, Tsitourides I, Athanassiou-Metaxa M. Evaluation of iron overload in beta-thalassemia patients using magnetic resonance imaging. Hemoglobin. 2004;28:45-49. |

| 7. | Brittenham GM, Badman DG. Noninvasive measurement of iron: report of an NIDDK workshop. Blood. 2003;101:15-19. |

| 8. | Candini G, Lappi S. Assessment of cardiac and hepatic iron overload in thalassaemic patients by magnetic resonance: a four year observational study. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2008;6 Suppl 1:204-207. |

| 9. | Scheuer PJ, Williams R, Muir AR. Hepatic pathology in relatives of patients with haemochromatosis. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1962;84:53-64. |

| 10. | Maggio A, Capra M, Pepe A, Mancuso L, Cracolici E, Vitabile S, Rigano P, Cassarà F, Midiri M. A critical review of non invasive procedures for the evaluation of body iron burden in thalassemia major patients. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2008;6 Suppl 1:193-203. |

| 11. | Mazza P, Giua R, De Marco S, Bonetti MG, Amurri B, Masi C, Lazzari G, Rizzo C, Cervellera M, Peluso A. Iron overload in thalassemia: comparative analysis of magnetic resonance imaging, serum ferritin and iron content of the liver. Haematologica. 1995;80:398-404. |

| 12. | Christoforidis A, Haritandi A, Tsatra I, Tsitourides I, Karyda S, Athanassiou-Metaxa M. Four-year evaluation of myocardial and liver iron assessed prospectively with serial MRI scans in young patients with beta-thalassaemia major: comparison between different chelation regimens. Eur J Haematol. 2007;78:52-57. |