Published online Oct 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i37.4247

Revised: March 2, 2011

Accepted: March 9, 2011

Published online: October 7, 2011

Johanson-Blizzard syndrome (JBS) is a rare autosomal recessive disease characterized by exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, hypoplastic or aplastic nasal alae, cutis aplasia on the scalp, and other features including developmental delay, failure to thrive, hearing loss, mental retardation, hypothyroidism, dental abnormalities, and anomalies in cardiac and genitourinary systems. More than 60 cases of this syndrome have been reported to date. We describe the case of a male infant with typical symptoms of JBS. In addition, a new clinical feature which has not previously been documented, that is anemia requiring frequent blood transfusions and mild to moderate thrombocytopenia was observed. A molecular study was performed which revealed a novel homozygous UBR1 mutation. Possible explanations for this new association are discussed.

- Citation: Almashraki N, Abdulnabee MZ, Sukalo M, Alrajoudi A, Sharafadeen I, Zenker M. Johanson-Blizzard syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(37): 4247-4250

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i37/4247.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i37.4247

Johanson-Blizzard syndrome (JBS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder, first described in 1971 by Johanson and Blizzard[1]. The genetic defect causing the disease was unknown until 2005, when it was shown to result from mutations of the UBR1 gene located on chromosome 15q15-21. UBR1 encodes one of at least four functionally overlapping E3 ubiquitin ligases of the N-end rule pathway, a conserved proteolytic system whose substrates include proteins with destabilizing N-terminal residues 20[2]. The precise pathophysiological link between altered protein degradation and the clinical anomalies observed in JBS remains to be determined.

The reported cases of JBS showed no difference in gender. Parental consanguinity is frequently observed. The typical clinical features of JBS are the following (with decreasing frequency): exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, hypoplasia/aplasia of the alae nasi, dental anomalies, congenital scalp defects, sensorineural hearing loss, growth retardation, psychomotor retardation, hypothyroidism, imperforate anus and genitourinary anomalies. A detailed list of observed clinical features is given in Table 1.

| Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency[1,3-5] |

| Hypoplasia/aplasia of alae nasi[1,4,6-8] |

| Scalp defect /aplasia cutis[1,6,8] |

| Sensory neural hearing loss[1,3,8,9] |

| Bilateral cystic dilation of cochlea, low set ears, and temporal bone defect[10] |

| Growth retardation, short stature[1,11] |

| Dental anomalies: oligodontia and absence of permanent teeth[1,6,7,11] |

| Anorectal anomalies: imperforate anus[4,11,12] |

| Hypotonia, microcephaly, and mental retardation sometimes normal intelligence[3,7,11] |

| lacrimal duct anomalies, coloboma of the lids, superior puncta absence, lacrimal cutaneous fistula, and congenital cataract[13] |

| Abnormal frontal hair pattern (upsweep)[7] |

| Vesicoureteric reflux, hypospadia, and duplex of uterine and vagina[8] |

| Congenital heart diseases such as myxomatous mitral valve, PDA, VSD, ASD, dextrocardia, complex congenital heart disease, and cardiomyopathy[13,14] |

| Cholestatic liver disease (one case)[15] |

| Café au lait spots[16] |

| Hypothyroidism[1] |

| Growth hormone deficiency[5] |

| Hypopituitarism[17] |

| Impaired glucagon secretion response to insulin induced hypoglycemia[18] |

| Diabetes mellitus[19,20] |

A 5-mo-old male infant of consanguineous Yemeni parents was referred because of poor feeding. The history started when he was 2-mo old with recurrent attacks of pallor and edema in the feet and hands. In addition, the infant showed failure to thrive and greasy stools. He received 3 blood transfusions. There was a family history of two previous male siblings with the same facial features as the index case, who also received several blood transfusions and expired at 4 and 4 ½ mo, respectively

On physical examination, the patient was lethargic, hypotonic, and pale. His body weight was 3.3 kg (< 5% percentile), and body length was 52 cm (< 5% percentile). Head circumference was 37 cm (microcephaly), and the anterior fontanel was wide (6 cm × 3 cm). There was aplasia of the alae nasi, midline cutis aplasia and a small scalp defect on the occiput, the scalp hair was sparse with areas of alopecia (Figure 1), and eye lashes and eyebrows were sparse. Hypospadias was detected, and the anus was narrow and displaced anteriorly. There was also pitting edema on the feet and hands.

Routine laboratory tests revealed the following results: hemoglobin (Hb) was 4 g/dL, with reticulocytes 7%, mean corpuscular volume 85 fl and mildly decreased platelets (75 000/μL). Erythrocyte morphology showed anisocytosis and normochromia. Hb electrophoresis and bone marrow aspiration were normal (Table 2).

| At presentation (5 mo) | At 9 mo | Normal range | |

| Hemoglobin | 4 g/dL | 11.7g/dL | 10.5-12 |

| Post transfusion: 12 g/dL, | |||

| Retics count | 7% | 1.20% | 0.2-2% |

| MCV | 85 | 85 | 70-86 fl |

| Leukocyte count | 5600 | 16 000 | 6000-17 500/mm3 |

| Platelets | 192 000, 79 000, 100 000 | 390 000 | 150 000-400 000/mm |

| RBC blood morphology | Anisocytosis and normochromia | Anisocytosis and normochromia | |

| Total bilirubin | 3.5 | 3 | 0-24 mmol/L |

| Direct bilirubin | 1.5 | 1.13 | 0-5.1 mmol/L |

| ALT | 44 | 39 | 0-41 U/L |

| AST | 45 | 55 | 0-35 U/L |

| ALP | 235 | 410 | 180-1200 U/L |

| Total protien | 35 | 56 | 60-87 g/L |

| Albumin | 17.3 | 38.8 | 34-48 g/dL |

| Urea | 1 | 1.7 | 3.3-6.4 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 13 | 19 | 62-106 mmol/L |

| Pancreatic amylase | 2.96 | 15 | 13-53 U/L |

| Pancreatic lipase | 10 | 20 | 13-60 U/L |

| FT4 | 9.28 | 11.55 | 13.9-26.1 pmol/L |

| TSH | 17.8 | 6.43 | 1.4-8.8 ulU/mL |

| Serum iron | 88.39 | 157 | 60-170 mg L/dL |

| Total iron binding capacity | 120 | 106 | 100-400 mg/dL |

| Serum ferritin | 1260 (repeated BT) | 7-140 ng/mL | |

| Serum folate level | 20 | 15-55 ng/mL | |

| Serum vitamin B12 level | 252 | 197-866 pg/mL | |

| Insulin | 0.2 | 2.6-24.9 Uu/mL | |

| Bone marrow results (normal) | Erythropoiesis, granulopoiesis, and lymphopoiesis are normal cellularity and maturity and megakaryocytes are present | The same result | |

| Hemoglobin electrophoresis | Normal |

Serum pancreatic enzymes (amylase, lipase) were low. Total protein and albumin were low, and other liver function tests, renal function tests, serum electrolytes and blood sugar were within the normal range (Table 2).

Thyroid function tests revealed low free T4 and slightly increased thyroid-stimulating hormone. These results indicated hypothyroidism.

Echocardiography showed a small atrial septal defect. Whole body X-ray, abdominal ultrasound, brain computed tomography (CT) scan, and temporal bone CT scan were normal.

The patient received oral thyroxine, pancreatic enzyme replacement, multivitamins and strict monitoring to avoid complications. When the patient was seen last time at the age of 9 mo, his overall condition had significantly improved. He has gained weight, although still below the 3rd centile, and blood cell counts had normalized (Table 2). The child still showed muscular hypotonia and delay in motor milestones.

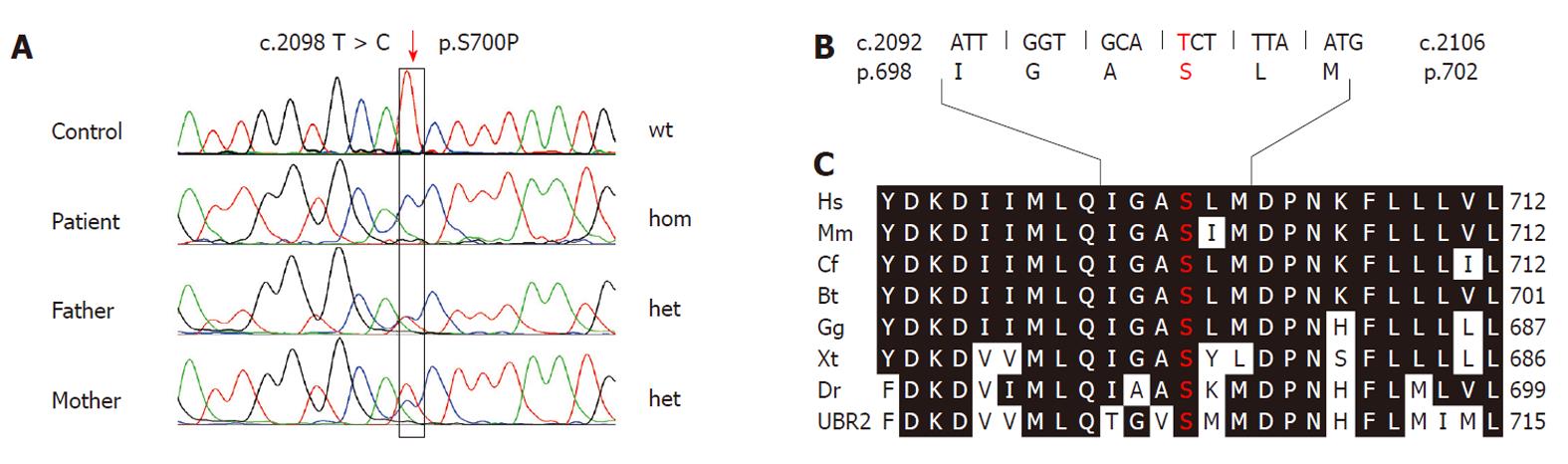

After obtaining informed written consent from the parents for the genetic investigation, venous blood samples were taken from the index patient and his parents. DNA was extracted from blood leukocytes according to standard procedures. All 47 exons of the UBR1 gene including the flanking intronic regions were analyzed by direct bidirectional sequencing as described previously[19]. Sequencing in the index patient revealed a homozygous mutation in exon 19. The nucleotide substitution c.2089 C > T predicts a missense change (p.S700P) affecting an amino acid residue that is 100% conserved throughout vertebrate UBR1 and UBR2 proteins (Figure 2). To date, this change has not been known as a mutation or polymorphism. PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) predicts that this mutation is probably damaging with a score of 0.992 (sensitivity: 0.59; specificity: 0.96). Both parents were found to be heterozygous for the mutation. Based on this evidence we regarded p.S700P as the disease-causing mutation in this family.

JBS is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that affects many systems with a wide range of congenital abnormalities. A small beak-like nose (due to aplasia or hypoplasia of the alae nasi), and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency are considered the most consistent manifestations, while others features (Table 1) occur at varying frequencies in the affected patients. The patient presented here had typical facial features and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, this combination is pathognomonic for JBS. Our patient also presented with scalp defects, developmental delay, and generalized hypotonia, which have been described in reported cases of JBS. Remarkably, our patient presented with an additional phenotypic feature, namely significant anemia, and required frequent blood transfusions from the age of 2 mo. The hematologic abnormalities also included thrombocytopenia and mild leukopenia. No definite etiology could be established. This feature has not been described in previous reports of JBS. Remarkably, two previous male siblings, who were assumed to have the same disease based on the report of similar facial features, also had significant anemia (Hb: 4 g/dL) and received frequent blood transfusions.

In addition, there was also mild to moderate thrombocytopenia in the other affected children of this family. The unusual and consistent association of JBS with a hematologic phenotype in this family may raise different speculations, such as a second autosomal recessive condition that might segregate JBS in this family or a specific function of the UBR1 protein carrying the novel missense mutation.

In infants, anemia caused by iron, vitamins and trace element deficiencies are unusual before the age of 6 mo, but in this patient the nutritional consequences of malabsorption might have appeared earlier due to many factors such as low birth weight, malnutrition in the mother and hypothyroidism in which normochromic, normocytic anemia may be secondary to reduced red blood cell production and reduced red cell survival.

Although we cannot exclude these possibilities, the fact that the hematologic disease resolved after efficient pancreatic enzyme and vitamin supplementation suggests a major contribution of malnutrition.

We thank the family for their kind cooperation.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Paul Sharp, BSc (Hons), PhD, Nutritional Sciences Division, King’s College London, Franklin Wilkins Building, 150 Stamford Street, London, SE19NH, United Kingdom

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Johanson A, Blizzard R. A syndrome of congenital aplasia of the alae nasi, deafness, hypothyroidism, dwarfism, absent permanent teeth, and malabsorption. J Pediatr. 1971;79:982-987. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Zenker M, Mayerle J, Lerch MM, Tagariello A, Zerres K, Durie PR, Beier M, Hülskamp G, Guzman C, Rehder H. Deficiency of UBR1, a ubiquitin ligase of the N-end rule pathway, causes pancreatic dysfunction, malformations and mental retardation (Johanson-Blizzard syndrome). Nat Genet. 2005;37:1345-1350. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Elting M, Kariminejad A, de Sonnaville ML, Ottenkamp J, Bauhuber S, Bozorgmehr B, Zenker M, Cobben JM. Johanson-Blizzard syndrome caused by identical UBR1 mutations in two unrelated girls, one with a cardiomyopathy. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:3058-3061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mcheik JN, Hendiri L, Vabres P, Berthier M, Cardona J, Bonneau D, Levard G. Johanson-Blizzard syndrome: a case report. Arch Pediatr. 2002;9:1163-1165. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sandhu BK, Brueton MJ. Concurrent pancreatic and growth hormone insufficiency in Johanson-Blizzard syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;9:535-538. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Gershoni-Baruch R, Lerner A, Braun J, Katzir Y, Iancu TC, Benderly A. Johanson-Blizzard syndrome: clinical spectrum and further delineation of the syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1990;35:546-551. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Barroso KMA, Leite DFB, Alves PM, de Medeiros PFV, Godoy GP. Johanson-Blizzard syndrome-A case study of oral and systemic manifestations. Int J Ped Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2009;5:180-182. |

| 8. | Rosanowski F, Hoppe U, Hies T, Eysholdt U. Johanson-Blizzard syndrome. A complex dysplasia syndrome with aplasia of the nasal alae and inner ear deafness. HNO. 1998;46:876-878. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Sismanis A, Polisar IA, Ruffy ML, Lambert JC. Rare congenital syndrome associated with profound hearing loss. Arch Otolaryngol. 1979;105:222-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Alpay F, Gül D, Lenk MK, Oğur G. Severe intrauterine growth retardation, aged facial appearance, and congenital heart disease in a newborn with Johanson-Blizzard syndrome. Pediatr Cardiol. 2000;21:389-390. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ghishan FK, Diarrhea C. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jensen HB, Stanton BF. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Alsevier 2007; Chapter 338. |

| 12. | Nagashima K, Yagi H, Kuroume T. A case of Johanson-Blizzard syndrome complicated by diabetes mellitus. Clin Genet. 1993;43:98-100. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Jones NL, Hofley PM, Durie PR. Pathophysiology of the pancreatic defect in Johanson-Blizzard syndrome: a disorder of acinar development. J Pediatr. 1994;125:406-408. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Cheung JC, Thomson H, Buncic JR, Héon E, Levin AV. Ocular manifestations of the Johanson-Blizzard syndrome. J AAPOS. 2009;13:512-514. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Al-Dosari MS, Al-Muhsen S, Al-Jazaeri A, Mayerle J, Zenker M, Alkuraya FS. Johanson-Blizzard syndrome: report of a novel mutation and severe liver involvement. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:1875-1879. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kulkarni ML, Shetty SK, Kallambella KS, Kulkarni PM. Johanson--blizzard syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:1127-1129. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Hoffman WH, Lee JR, Kovacs K, Chen H, Yaghmai F. Johanson-Blizzard syndrome: autopsy findings with special emphasis on hypopituitarism and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10:55-60. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Takahashi T, Fujishima M, Tsuchida S, Enoki M, Takada G. Johanson-blizzard syndrome: loss of glucagon secretion response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2004;17:1141-1144. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Steinbach WJ, Hintz RL. Diabetes mellitus and profound insulin resistance in Johanson-Blizzard syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2000;13:1633-1636. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Chopra SA, Chopra FS. Cancer in the Africans and Arabs of Zanzibar. Int J Cancer. 1977;19:298-304. [PubMed] |