Published online Sep 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i35.4048

Revised: May 19, 2011

Accepted: May 26, 2011

Published online: September 21, 2011

Dual antiplatelet therapy consisting of low-dose aspirin (LDA) and other antiplatelet medications is recommended in patients with coronary heart disease, but it may increase the risk of esophageal lesion and bleeding. We describe a case of esophageal mucosal lesion that was difficult to distinguish from malignancy in a patient with a history of ingesting LDA and prasugrel after implantation of a drug-eluting stent. Multiple auxiliary examinations were performed to make a definite diagnosis. The patient recovered completely after concomitant acid-suppressive therapy. Based on these findings, we strongly argue for the evaluation of the risk of gastrointestinal mucosal injury and hemorrhage if LDA therapy is required, and we stress the paramount importance of using drug combinations in individual patients.

- Citation: Ma GF, Gao H, Chen SY. Esophageal mucosal lesion with low-dose aspirin and prasugrel mimics malignancy: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(35): 4048-4051

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i35/4048.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i35.4048

Low-dose aspirin (LDA) is used widely as an antiplatelet therapy for the prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events[1]. Dual antiplatelet therapy is more effective than aspirin alone[2]. However, the risk of severe bleeding, including life-threatening hemorrhaging, increases with the use of aspirin therapy[3]. The most vulnerable organs are the stomach and duodenum, although recent reports indicate an increased risk of esophageal lesions with LDA use[4,5]. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends the use of aspirin for men aged 45 to 79 years when the potential benefit due to a reduction in myocardial infarction outweighs the potential harm due to an increase in gastrointestinal hemorrhage[6].

Prasugrel, a third-generation thienopyridine, specifically inhibits platelet clotting by binding the adenosine diphosphate receptor. Prasugrel is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). It’s recommended loading dose is 60 mg x1, followed by a maintenance dose (10 mg once daily), and combined with concomitant aspirin (81-325 mg, once daily)[7]. Compared to clopidogrel, prasugrel has been shown to reduce thrombotic cardiovascular events significantly, including stent thrombosis, in patients with ACS who are managed with PCI. However, prasugrel can cause significant and fatal bleeding, and it has a FDA black-box warning regarding bleeding risk[7]. Thus, patient selection is important.

Here, we present a case with esophageal lesion mimicking malignancy related to aspirin and prasugrel treatment after drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation.

A 58-year-old male was admitted in August 2010 because of melena and hematemesis. About 1.5 mo before admission, the patient underwent PCI and received a DES due to chest pain. Low-dose aspirin (100 mg, once per day) and prasugrel (Effient, 10 mg, once per day) were administered.

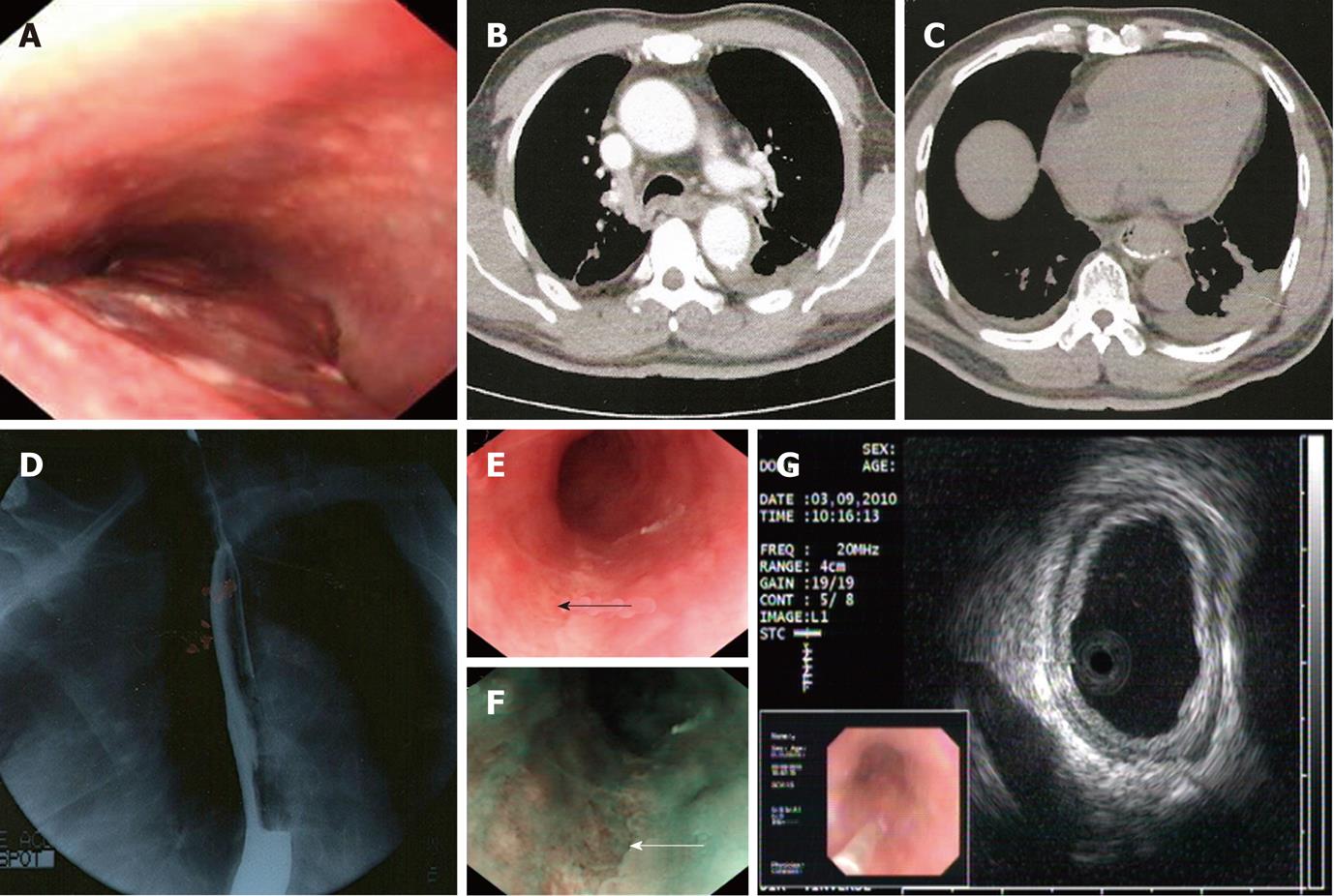

One month later, the patient felt epigastric discomfort accompanied by severe chest pain. Coronary arteriography was repeated without positive findings. Gastroendoscopy was then performed, which showed edematous esophageal mucosa with blood clots, a column of violaceous and nontortuous lesions with minimal whitish exudates that occupied more than half of the lumen from the 26 cm to the 42 cm level (Figure 1A). Esophageal candidiasis was suspected. Biopsy indicated that there were necrotic tissues with partly degenerated atypical fusiform to epithelioid cells of undetermined significance.

At 7 d before admission, the patient passed a dark pasty stool of about 250 g after taking some cathartics. Three days later, gastroendoscopy was performed in Shanghai Cancer Center, which revealed a slim ulcer from the 26 cm down to the 40 cm level. Pathology suggested inflammation and granuloma gangraenescens. Chest contrast computed tomography demonstrated thickening of the middle-lower segment of the esophageal wall and a few of the small lymph nodes at the mediastinum (Figure 1B and C) with some pleural effusion. An upper gastrointestinal series (barium X-ray) showed an irregular esophageal wall with stiff movement, and the possibility of malignant tumor could not be excluded (Figure 1D).

One day after the examination, the patient felt nauseous and vomited dark blood clots. He was sent urgently to our emergency room. After treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), he had no signs of active bleeding. He was transferred to the gastroenterology department for further diagnosis. Another gastroendoscopy was performed after intravenous PPI therapy for 1 wk. Endoscopy by white light imaging (WLI) and narrow band imaging (NBI) showed that the esophageal mucosa was peeled off (Figure 1E and F). Endoscopic ultrasonography suggested that the layers of the esophagus were clear and identifiable; the lesion took on a minimal higher echo (Figure 1G). Tumor markers were normal. Antiplatelet drugs were discontinued after admission, and symptoms improved within 7 d. Clopidogrel and oral PPI were administered afterwards. He was discharged on the 7th day. Two months later, endoscopy showed that the esophageal lesion had completely healed.

It was very difficult to identify the esophageal lesion in this patient. After the first gastroendoscopy showed edematous mucosa with blood clots, it was risky to perform a biopsy and difficult to recognize the lesion. It seemed to be a malignant tumor on the basis of the previous auxiliary examinations. Moreover, the accuracy of the biopsy was affected by the focal position and depth; such a situation could easily mislead medical providers.

If discrete erosions had occurred in areas away from the Z line, then drug-induced injury would have been strongly considered[8]. The occurrence of esophageal mucosal injury by LDA is related closely to the intragastric pH value, especially at night[9]. A multicenter randomized controlled trial documented that use of the NBI mode could improve the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopy, compared to the WLI mode[10]. When the auxiliary examination is not consistent with clinical symptoms, further diagnostic modalities are required. If all of the tests are inconclusive, then repeat examinations are needed to confirm or rule out the prior diagnosis after diagnostic treatment. The appropriate use of diverse and repeatable examinations to improve the accuracy of an uncertain disease is of great value.

Esophageal cancer develops rapidly and has a fatal prognosis. It has displayed an increasing incidence in the past decade, with the highest incidence in the age group of 50-70 years. The disease is diagnosed more frequently in males than in females, with an approximate ratio of 3-5[11]. Whether aspirin has implications for cancer prevention is debatable. Kawai et al[5] investigated 101 consecutive outpatients with cardiovascular diseases who had been on LDA therapy. They found that the incidence of esophageal lesions was 8.9%, whereas the rate of esophageal and gastric cancers was up to 5.9%. Abnet et al[12]

found no correlation between the self-reported use of aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and esophageal adenocarcinomas in a prospective cohort followed for 7 years. However, their meta-analysis manifested that aspirin use was inversely associated with esophageal adenocarcinomas, with a summary odds ratios for esophageal adenocarcinomas of 0.64. Considering these previous findings, we speculate that regular endoscopic surveillance might benefit patients on dual antiplatelet therapy.

Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage is an urgent life-threatening event that is commonly incited by a peptic ulcer or varices. However, evidence indicates that aspirin or other NSAIDs are another potential cause, especially in elderly patients with cardiac or cerebral events. A metaanalysis of 24 randomized controlled trials documented gastrointestinal hemorrhage in 2.47% of patients taking aspirin, compared with 1.42% taking placebo [Odds ratio (OR): 1.68], and no relationship was observed between gastrointestinal hemorrhage and dose[13]. Among 674 patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeds, the odds ratio for the presence of erosive esophagitis in aspirin users was 2 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1-3], and 3 (95% CI: 2-5) in patients taking other antithrombotic agents, including warfarin, clopidogrel, and dipyridamole. In 41 patients with esophagitis who were taking these drugs, 36 (88%) had cardiovascular disease and only 4 (10%) had peptic symptoms[14]. These findings suggest that the gastrointestinal risk should be determined, even if LDA is required.

The appropriate use of aspirin is complicated. It is difficult to determine how to balance the prevention of stent thrombosis with the potential injury of the gastrointestinal mucosa. The use of enteric-coated aspirin decreases mucosal damage in the short term, but does not decrease the risk of hemorrhagic gastrointestinal events compared with noncoated aspirin[15]. Yeomans et al[16]

investigated 991 patients who were randomized to take esomeprazole (20 mg, once per day) or placebo for 26 wk. They found that the cumulative proportion of patients with erosive esophagitis was significantly lower for esomeprazole vs placebo (4.4% vs 18.3%). Esomeprazole-treated patients were more likely to experience resolution of heartburn, acid regurgitation, and epigastric pain.

On the other hand, insufficient antithrombotic drugs might cause stent thrombosis. In November 2009, the FDA warned that the effectiveness of clopidogrel was reduced when clopidogrel and omeprazole were taken together. Warner et al[17] reported that the use of aspirin in the presence of prasugrel could increase the clinical risk of residual ischemic events and bleeding complications. Whether dual antiplatelet therapy should be prescribed routinely to high-risk patients requires a complete understanding of its long-term consequences. In particular, for an individual patient, this decision must consider the trade-off between the potential benefits of preventing ischemic events weighed against the risk of bleeding complications.

Drug combinations must be prudently selected for individual patients. Compared with the second-generation clopidogrel (Plavix), prasugrel is more potent, faster in onset, and more consistent in inhibiting platelets, but bleeding complications are more frequent[18]. From the aspect of clinical and cost effectiveness, prasugrel in combination with aspirin could be an option for preventing atherothrombotic events in people having ACS with PCI only when immediate primary PCI for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction is necessary, stent thrombosis has occurred during clopidogrel treatment, or in cases of diabetes mellitus. Prasugrel should be used with caution in patients at an increased risk of bleeding, especially in patients who are ≥ 75 years old with a tendency to bleed or with body weight of < 60 kg[19]. A guideline has recommended that clopidogrel should be continued for at least 12 mo for patients who receive a DES[7,19]. A randomized controlled trial found no apparent cardiovascular interaction between clopidogrel and omeprazole, and prophylactic use of a PPI reduced the rate of upper gastrointestinal bleeding[20]. Thus, for such patients with a high risk of bleeding, clopidogrel plus PPI might be a better recommendation to decrease the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

In conclusion, this case report of a patient developing an esophageal mucosal lesion mimicking malignancy while under LDA and prasugrel treatment highlights the need to evaluate the gastrointestinal risk if LDA therapy is required. The findings also stress the importance of the rational selection of drug combinations in individual patients.

Peer reviewers: Bronislaw L Slomiany, PhD, Professor, Research Center, C-875, UMDNJ-NJ Dental School, 110 Bergen Street, PO Box 1709, Newark, NJ 07103-2400, United States; Dr. Ping-Chang Yang, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, McMaster University, BBI-T3330, 50 Charlton Ave East, Hamilton, L8N 4A6, Canada

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4959] [Cited by in RCA: 4590] [Article Influence: 199.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J. Combined antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy: clinical benefits and risks. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5 Suppl 1:255-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | May AE, Geisler T, Gawaz M. Individualized antithrombotic therapy in high risk patients after coronary stenting. A double-edged sword between thrombosis and bleeding. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:487-493. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Yamamoto T, Mishina Y, Ebato T, Isono A, Abe K, Hattori K, Ishii T, Kuyama Y. Prevalence of erosive esophagitis among Japanese patients taking low-dose aspirin. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:792-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kawai T, Watanabe M, Yamashina A. Impact of upper gastrointestinal lesions in patients on low-dose aspirin therapy: preliminary study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25 Suppl 1:S23-S30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: U. S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:396-404. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Antithrombotic therapy supplement (Guideline). 10th ed. Bloomington (MN): Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI); 2011; 43-45 Available from: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=32824&search=antithrombotic+therapy+supplement or http://www.icsi.org/antithrombotic_therapy_supplement__guideline__14045/antithrombotic_therapy_supplement__guideline_.html. |

| 8. | O'Neill JL, Remington TL. Drug-induced esophageal injuries and dysphagia. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:1675-1684. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Sugimoto M, Nishino M, Kodaira C, Yamade M, Ikuma M, Tanaka T, Sugimura H, Hishida A, Furuta T. Esophageal mucosal injury with low-dose aspirin and its prevention by rabeprazole. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50:320-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Muto M, Minashi K, Yano T, Saito Y, Oda I, Nonaka S, Omori T, Sugiura H, Goda K, Kaise M. Early detection of superficial squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck region and esophagus by narrow band imaging: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1566-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 427] [Cited by in RCA: 525] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kollarova H, Machova L, Horakova D, Janoutova G, Janout V. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer--an overview article. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2007;151:17-20. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Abnet CC, Freedman ND, Kamangar F, Leitzmann MF, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of gastric and oesophageal adenocarcinomas: results from a cohort study and a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:551-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Derry S, Loke YK. Risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage with long term use of aspirin: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2000;321:1183-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 482] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Taha AS, Angerson WJ, Knill-Jones RP, Blatchford O. Upper gastrointestinal mucosal abnormalities and blood loss complicating low-dose aspirin and antithrombotic therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:489-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sørensen HT, Mellemkjaer L, Blot WJ, Nielsen GL, Steffensen FH, McLaughlin JK, Olsen JH. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with use of low-dose aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2218-2224. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Yeomans N, Lanas A, Labenz J, van Zanten SV, van Rensburg C, Rácz I, Tchernev K, Karamanolis D, Roda E, Hawkey C. Efficacy of esomeprazole (20 mg once daily) for reducing the risk of gastroduodenal ulcers associated with continuous use of low-dose aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2465-2473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Warner TD, Armstrong PC, Curzen NP, Mitchell JA. Dual antiplatelet therapy in cardiovascular disease: does aspirin increase clinical risk in the presence of potent P2Y12 receptor antagonists? Heart. 2010;96:1693-1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lazar LD, Lincoff AM. Prasugrel for acute coronary syndromes: faster, more potent, but higher bleeding risk. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76:707-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Prasugrel for the treatment of acute coronary syndromes with percutaneous coronary intervention. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2009; 4-5 Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA182. |

| 20. | Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, Cohen M, Lanas A, Schnitzer TJ, Shook TL, Lapuerta P, Goldsmith MA, Laine L. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909-1917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 843] [Article Influence: 56.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |