Published online Sep 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i33.3850

Revised: February 22, 2011

Accepted: February 28, 2011

Published online: September 7, 2011

AIM: To improve the diagnosis of heterotopic pancreas by the use of contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) imaging and CT virtual endoscopy (CTVE).

METHODS: A total of six patients with heterotopic pancreas, as confirmed by clinical pathology and immunohistochemistry in the Sixth Affiliated People’s Hospital of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, were included. Non-enhanced CT and enhanced CT scanning were performed, and the resulting images were reviewed and analyzed using three-dimensional post-processing software, including CTVE.

RESULTS: Four males and two females were enrolled. Several heterotopic pancreas sites were involved; three occurred in the stomach, including the gastric antrum (n = 2) and lesser curvature (n = 1), and two were in the duodenal bulb. Only one case of heterotopic pancreas lesion occurred in the mesentery. Four cases had a solid yet soft tissue density that had a homogeneous pattern when viewed by enhanced CT. Additionally, their CT values were similar to that of the pancreas. The ducts of the heterotopic pancreas tissue, one of the characteristic CT features of heterotopic pancreas tissue, were detected in the CT images of two patients. CTVE images showed normal mucosa around the tissue, which is also an important indicator of a heterotopic pancreas. However, none of the CTVE images showed the typical signs of central dimpling or umbilication.

CONCLUSION: CT, enhanced CT and CTVE techniques provide useful information about the location, growth pattern, vascularity, and condition of the gastrointestinal wall around heterotopic pancreatic tissue.

- Citation: Wang D, Wei XE, Yan L, Zhang YZ, Li WB. Enhanced CT and CT virtual endoscopy in diagnosis of heterotopic pancreas. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(33): 3850-3855

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i33/3850.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i33.3850

Heterotopic pancreas is a condition in which pancreatic tissue is found outside the boundaries of the normal pancreas; such tissue is regarded as aberrant pancreas or an accessory pancreatic lesion. This tissue has no anatomical, vascular or neuronal connection with the main pancreas. Such anomalies can become apparent at any age, but they are most commonly found in the fourth, fifth and sixth decades of life, with a slight male predominance. Heterotopic pancreas frequently occurs in association with the gastrointestinal tract (stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum) but is also found associated with Meckel’s diverticulum, mesentery, omentum, spleen, and gallbladder[1]. In mice, the formation of a heterotopic pancreas may be caused by inactivation of the gene IPF-1 (also known as IDX-1, STF-1 or PDX), which leads to errors in embryological development that can result in the total absence of the pancreas[1]. Symptoms are dependent on the location of the ectopic tissue, although the most common symptoms are epigastric pain, pyloric obstruction, cholecystitis, and intussusception[1,2]. Some cases are identified as a result of such symptoms, but others are identified incidentally, such as during an unrelated surgery or during autopsy[1,3,4].

Cases of heterotopic pancreas have been reported in recent years following descriptions of the general characteristics of the condition observed by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). However, recent improvements in multi-slice computed tomography (CT) technology and the wide use of enhanced CT scanning have provided a new approach for identifying heterotopic pancreas. In this study, we present six cases of heterotopic pancreas and highlight the associated CT features[5].

We retrospectively analyzed our database of all patients (about 350 000 patients) who underwent CT scanning at the Shanghai 6th People’s Hospital Affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University from January 2000 to December 2010. Six cases (four males, two females) were selected who were definitively diagnosed with heterotopic pancreatic tissue postoperatively by pathological examination and immunohistochemistry. With the exception of one patient aged 3 mo and another aged 38 years, the subjects were all aged between 59 and 68 years (Table 1). Three patients complained of epigastric pain or abdominal distension, and two others presented with cachexia or carcinoid syndrome. The other case was identified incidentally (Table 1). This study was reviewed and approved by the Shanghai 6th People’s Hospital Affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

| Case | Gender | Age | Symptom | Location | Growth pattern and modality |

| 1 | M | 60 yr | Carcinoid syndrome | Duodenal bulb | Exogenous, superficially lobulated, well-defined border, subserosal outer boundary was rough |

| 2 | F | 59 yr | Epigastric pain (3 wk) | Gastric antrum | Circumscribed tissue, ill-defined border |

| 3 | M | 68 yr | Epigastric pain (1 yr) | Gastric antrum | Circumscribed tissue, superficially lobulated, ill-defined border |

| 4 | F | 3 mo | Identified during choledochal cystectomy | Mesentery | No obvious abnormality detected by computed tomography |

| 5 | M | 60 yr | Abdominal distension (2 mo) | Lesser curvature aspect of gastric antrum | Superficially lobulated, well-defined border |

| 6 | M | 38 yr | Cachexia | Duodenal bulb | Exogenous, well-defined border |

Multi-slice CT scanning was performed in all of the six cases using the LightSpeed VCT (GE) or Sensation CT (SIEMENS). No abnormality was detected in one of the female patients who therefore did not undergo contrast-enhanced CT scanning. The other five cases underwent enhanced CT scanning after standard CT scanning. With the exception of the 3-mo-old infant, the patients were asked to hold their breath during the scan in order to reduce artifacts. The thickness of the scanning slices was either 5 mm or 7 mm. The CT data of some patients was further refined using reconstruction software, which enabled thinner slice data to be obtained. The reconstruction software was all supplied by multi-slice CT; this was one function of the multi-slice CT. After the reconstruction the thinnest slice was 0.625 mm.

Each patient received the contrast agent iopromide (dose, 50-70 mL) through the median cubital vein. The arterial phase scan was produced approximately 30 s after the start of the injection. Coronal and sagittal images were obtained, and scanning data were analyzed on the GE workstation ADW 4.3. Lesion sizes were measured, and CT values were calculated (Table 1). Images were analyzed by application of three-dimensional post-processing software, including CT virtual endoscopy (CTVE).

The six patients comprised four males (aged 38, 60, 60 and 69 years) and two females (aged 3 mo and 59 years). All five adult patients had experienced symptoms over a period of time ranging from weeks to years. Three of the patients presented with symptoms that were directly indicative of gastrointestinal disease, which made the lesions simpler to identify. However, two of the patients had non-specific symptoms, including carcinoid syndrome or cachexia associated with other systemic diseases. As these symptoms did not directly indicate a heterotopic pancreas, the lesions were more difficult to identify. They were discovered after physical examination and other tests. The 3-mo-old girl was jaundiced, and although CT scanning revealed the presence of a choledochal cyst, the heterotopic pancreatic tissue that indeed was later found to be present in the mesentery was not detected (Table 1).

The CT values of the heterotopic pancreatic tissues were calculated, and these ranged from -47.8 to 43.3 Hu (Table 2). The density measured in four cases was indicative of soft tissue, and this density correlated with the fatty tissue in only one case. The lesions were frequently superficially lobulated, with circumscribed borders, and they protruded into the gastrointestinal cavity or peritoneal cavity. After carrying out contrast-enhanced CT, the CT value of each lesion was based on the arterial phase scanning data. The three soft tissue lesions were homogeneously enhanced to varying extents. The other two lesions were heterogeneously enhanced (Table 2).

| CT scanning | Enhanced CT scanning | ||||||

| Lesion | Pancreas | Lesion1 | Pancreas1 | ||||

| Case | Lesion dimensions (cm3) | CT value (Hu) | CT value (Hu) | CT value (Hu) | CT value (Hu) | Properties | Enhancement pattern |

| 1 | 1.8 × 1.2 × 2.1 | 38.2 | 44.3 | 93.2 | 97.4 | Solid | Homogeneous, highly enhanced |

| 2 | 1.2 × 1.0 × 2.1 | 28.2 | 44.7 | 80 | 106.9 | Solid | Homogeneous, slightly enhanced |

| 3 | 2.0 × 1.3 × 2.0 | 6.9 | 41.5 | 13.5 | 95.5 | Solid | Heterogeneous, slightly enhanced |

| 5 | 1.7 × 1.9 × 2.0 | –47.8 | 47.6 | –35.8 | 93.4 | Cystic with density of fat | Heterogeneous, slightly enhanced |

| 6 | 1.9 × 1.3 × 1.0 | 43.3 | 47.1 | 29.1 | 106.6 | Solid | Homogeneous, highly enhanced |

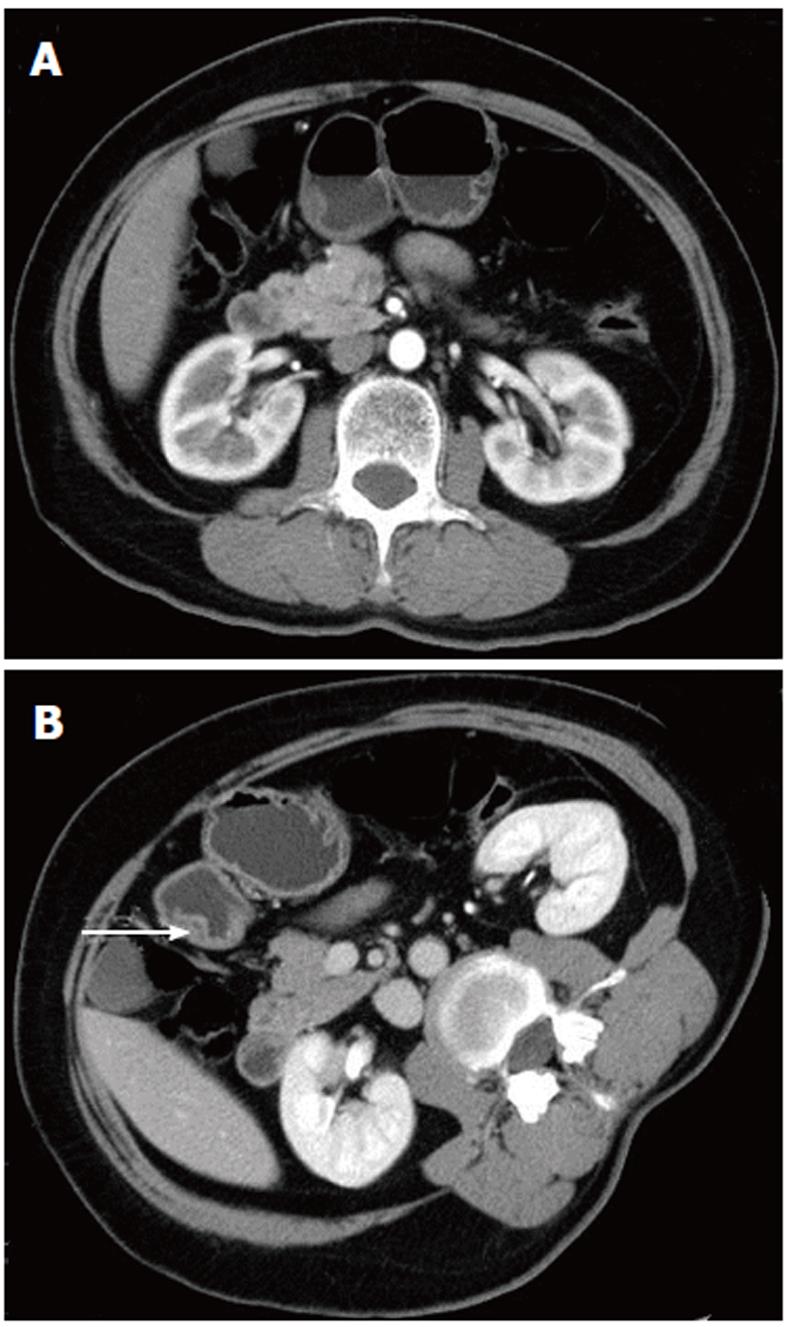

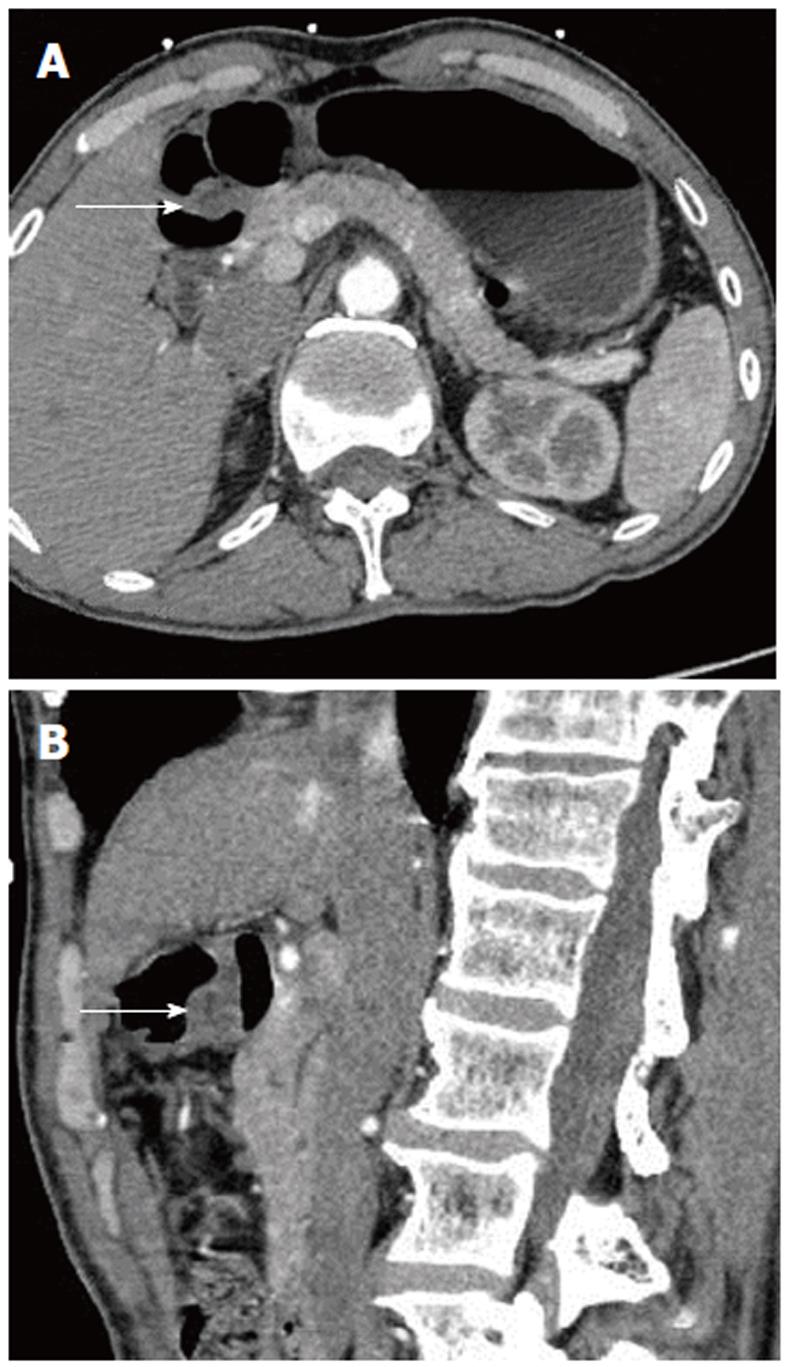

The scanning data were analyzed in depth using the GE workstation. The lesions could be seen from any angle in addition to the traditional axial, coronal, and sagittal views. Post-processing software was used to reveal further detail. In two cases, there was a strip of low density, which could be seen in both the axial and sagittal images; this may have represented the duct of the heterotopic pancreas (Figures 1 and 2).

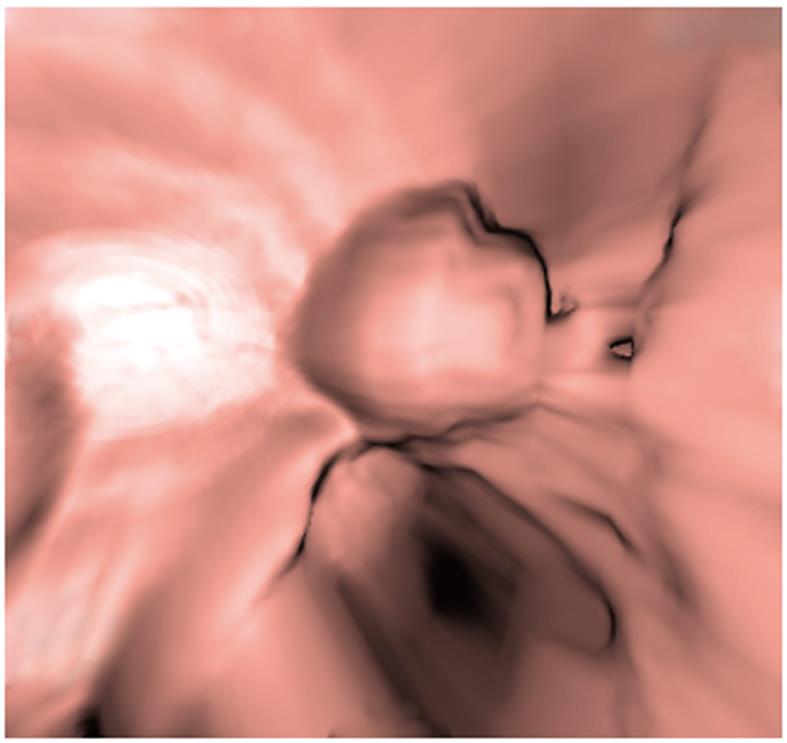

CTVE imaging of each entire lesion revealed structural features of the mass, such as a spherical shape and superficial lobulation, amongst others. This also aided in identifying the layer of the gastrointestinal wall in which the lesion was located, and it showed that the mucosa around the lesion was normal (Figure 3).

The incidence of heterotopic pancreas is low, with only 40% of patients experiencing symptoms and 60% of cases being found incidentally during surgery for other disorders[6-9]. Although CT scanning is a highly sensitive technique, it can still be difficult to detect this abnormality. In this study, a heterotopic pancreas was detected in five of six patients by means of CT scanning. Moreover, contrast-enhanced CT scanning should always be performed, when possible. Heterotopic pancreatic tissue was not observed in only one patient - the infant. For that patient, we postoperatively analyzed the CT images, but the lesion was still undetectable. As the intestines had expanded due to gas and liquid accumulation, as is commonly seen in infants, some of the intestines congregated at the mesenteric root.

In this study, 83.3% (five of six lesions) of the heterotopic pancreas lesions we observed occurred in the stomach, duodenum, and jejunum. In the stomach, 80%-90% of the lesions occurred in the antrum, within 5 to 6 cm of the pylorus[1,10,11]. Two of the three lesions that occurred in the stomach were located in the antrum (Figure 1). Heterotopic pancreas rarely occurs outside the gastrointestinal wall in tissues such as the liver, lung, omentum, mesentery, umbilicus, mediastinum, and fallopian tube[1,11-14].

Histologically, heterotopic pancreas is composed of ductal components, acinar cells, and islet cells. Because of differences in the proportions of the three components, however, the density of heterotopic pancreas tissue can vary[15]. In our study, lesions in four cases were composed of solid soft tissue, which was the commonest type. With the borders being defined to a variable extent, the density was similar to that of the main pancreas in 75% (3/4) of the cases of this type. Both the non-enhanced and contrast-enhanced CT images were analyzed, and the CT value of each lesion was measured (Table 2). These tissues were also homogeneously enhanced and were similar to the pancreas[16]. Only one case had a heterogeneous enhancement density that was typical of fatty tissue, and this was initially misdiagnosed as a lipoma. Therefore, lesions of the gastrointestinal tract having a density equivalent to fat should be additionally screened for a potential diagnosis of heterotopic pancreas.

Besides the density types discussed above, there is also a less common mixed-density cyst/solid type that was not observed in our study. This has also been considered as a complication of heterotopic pancreas[7,17]. Kim et al[14] reported that heterotopic pancreas with predominantly pancreatic acini shows a homogeneous enhancement pattern, whereas lesions with a mixed composition of acini and ducts show a heterogeneous enhancement. In our study, two cases showed a low-density strip of tissue with a well-defined border in the middle of the heterotopic pancreas lesion. In one case, the low-density strip was peripherally enhanced and so may have been the duct of the heterotopic pancreas[13].

Further thin-slice image data were obtained using the multi-slice CT, showing more details of each lesion, such as the interior density, enhancement pattern, location, and the duct. The thin-slice images also yielded high-quality two-dimensional and three-dimensional representations. With selection of the optimal viewing angle for the two-dimensional image, the low-density strip was shown to a greater extent; the presence of this strip is thus one of the characteristics of a heterotopic pancreas. Using EUS, Ryu et al[18] also identified the anechoic duct structure in some cases of heterotopic pancreas. Other work has shown that EUS may be more useful than CT in visualizing the pancreatic ducts[19]. In our study, however, the very small, narrow ducts were detectable only upon analysis of thin-slice two-dimensional contrast-enhanced images, and they were not detectable by EUS in the same patients. Therefore, we found that CT images were more sensitive for detecting the heterotopic pancreas duct.

CTVE is a three-dimensional display technology used in the post-processing of CT scanning data to reconstruct three-dimensional cavity surface images of hollow organs, and it provides images that are similar in detail to those obtained by endoscopy (Figure 3). The mucosa around all lesions we observed was normal. The gastrointestinal mucosa seemed to be undamaged and enhanced[14]. This was an important sign in the diagnosis of heterotopic pancreas.

The features of the heterotopic pancreas have been confirmed by endoscopy[20]. The lesions we observed were superficially lobulated, but none of the cases in our study exhibited typical heterotopic pancreas features, such as central dimpling or umbilication[21]. Notably, Ryu et al[18] also did not observe such umbilication. Hazzan et al[10] suggested that, although central umbilication of the lesion is one of the characteristic features of a heterotopic pancreas, it is difficult to diagnose because umbilication is often absent in tumors of less than 1.5 cm in diameter. This may explain why umbilication was not observed in our study, i.e., because the lesions were small.

In conclusion, CT scanning, contrast-enhanced CT scanning and CTVE provide useful information about heterotopic pancreas tissue and reveal some of its characteristic features. This combined-technique approach represents a novel way of recognizing and diagnosing the disease. Although these techniques have some limitations, they have been shown to be beneficial for preoperative diagnosis of heterotopic pancreas and therefore may influence the choice of surgical procedure. Resection of heterotopic pancreas tissue is advisable in order to avoid later complications and a second operation[22,23,24].

Heterotopic pancreas has a low incidence, and most affected individuals are asymptomatic. Previous reports describe the identification of heterotopic pancreas through endoscopic ultrasonography, but few studies have focused on the potential benefits of computed tomography (CT) and contrast-enhanced images. With the improvement in multi-slice CT technology and the widely used post-processing software, this approach provides a new way to detect the features of heterotopic pancreas.

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have focused on the application of contrast-enhanced CT scanning, post-processing software, and Computed tomography virtual endoscopy (CTVE) technology for the diagnosis of heterotopic pancreas.

CT scanning revealed the location and enhanced features of the lesion. CTVE showed the location, size, and shape of lesions as well as the organs with which they were associated; it also could visualize lumen stenosis and the surrounding mucosa. CTVE is also a reliable way to show the duct of heterotopic pancreas tissue. The advantages of this approach are that it is non-invasive and can reveal the extent of disease.

The findings of this study will be advantageous for the preoperative diagnosis of heterotopic pancreas. The approach also demonstrates a new use of CTVE.

It is an interesting proposition, even though founded on retrospective analysis.

Peer reviewers: Edward L Bradley III, MD, Professor of Surgery, Department of Clinical Science, Florida State University College of Medicine, 1600 Baywood Way, Sarasota, FL 34231, United States; Sara Regnér, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Institution of Clinical Sciences Malmo, Malmo University Hospital, Ing 82B, Universitetssjukhuset MAS, Malmö, SE-205 02, Sweden; Clement W Imrie, Professor, BSc(Hons), MB, ChB, FRCS, Lister Dept of Surgery, Glasgow Royal Infirmary, 11 Penrith Avenue, G46 6LU, Glasgow, United Kingdom

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Slack JM. Developmental biology of the pancreas. Development. 1995;121:1569-1580. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Elpek GO, Bozova S, Küpesiz GY, Oğüş M. An unusual cause of cholecystitis: heterotopic pancreatic tissue in the gallbladder. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:313-315. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Burke GW, Binder SC, Barron AM, Dratch PL, Umlas J. Heterotopic pancreas: gastric outlet obstruction secondary to pancreatitis and pancreatic pseudocyst. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:52-55. [PubMed] |

| 4. | DeBord JR, Majarakis JD, Nyhus LM. An unusual case of heterotopic pancreas of the stomach. Am J Surg. 1981;141:269-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim JH, Eun HW, Goo DE, Shim CS, Auh YH. Imaging of various gastric lesions with 2D MPR and CT gastrography performed with multidetector CT. Radiographics. 2006;26:1101-116; discussion 1101-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Canbaz H, Colak T, Düşmez Apa D, Sezgin O, Aydin S. An unusual cause of acute abdomen: mesenteric heterotopic pancreatitis causing confusion in clinical diagnosis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2009;20:142-145. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ormarsson OT, Gudmundsdottir I, Mårvik R. Diagnosis and treatment of gastric heterotopic pancreas. World J Surg. 2006;30:1682-1689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sandrasegaran K, Maglinte DD, Cummings OW. Heterotopic pancreas: presentation as jejunal tumor. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W607-W609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Erkan N, Vardar E, Vardar R. Heterotopic pancreas: report of two cases. JOP. 2007;8:588-591. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hazzan D, Peer G, Shiloni E. Symptomatic heterotopic pancreas of stomach. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:388-389. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lai CS, Ludemann R, Devitt PG, Jamieson GG. Image of the month. Heterotopic pancreas. Arch Surg. 2005;140:515-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jiang LX, Xu J, Wang XW, Zhou FR, Gao W, Yu GH, Lv ZC, Zheng HT. Gastric outlet obstruction caused by heterotopic pancreas: A case report and a quick review. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6757-6759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Khashab MA, Cummings OW, DeWitt JM. Ligation-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection of gastric heterotopic pancreas. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2805-2808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim JY, Lee JM, Kim KW, Park HS, Choi JY, Kim SH, Kim MA, Lee JY, Han JK, Choi BI. Ectopic pancreas: CT findings with emphasis on differentiation from small gastrointestinal stromal tumor and leiomyoma. Radiology. 2009;252:92-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hammock L, Jorda M. Gastric endocrine pancreatic heterotopia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:464-467. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Christodoulidis G, Zacharoulis D, Barbanis S, Katsogridakis E, Hatzitheofilou K. Heterotopic pancreas in the stomach: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6098-6100. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Jovanovic I, Knezevic S, Micev M, Krstic M. EUS mini probes in diagnosis of cystic dystrophy of duodenal wall in heterotopic pancreas: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2609-2612. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ryu DY, Kim GH, Park do Y, Lee BE, Cheong JH, Kim DU, Woo HY, Heo J, Song GA. Endoscopic removal of gastric ectopic pancreas: an initial experience with endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4589-4593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pessaux P, Lada P, Etienne S, Tuech JJ, Lermite E, Brehant O, Triau S, Arnaud JP. Duodenopancreatectomy for cystic dystrophy in heterotopic pancreas of the duodenal wall. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:24-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gurocak B, Gokturk HS, Kayacetin S, Bakdik S. A rare case of heterotopic pancreas in the stomach which caused closed perforation. Neth J Med. 2009;67:285-287. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Shi HQ, Zhang QY, Teng HL, Chen JC. Heterotopic pancreas: report of 7 patients. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2002;1:299-301. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Yang L, Zhang HT, Zhang X, Sun YT, Cao Z, Su Q. Synchronous occurrence of carcinoid, signet-ring cell carcinoma and heterotopic pancreatic tissue in stomach: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7216-7220. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Gokhale UA, Nanda A, Pillai R, Al-Layla D. Heterotopic pancreas in the stomach: a case report and a brief review of the literature. JOP. 2010;11:255-257. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Yuan Z, Chen J, Zheng Q, Huang XY, Yang Z, Tang J. Heterotopic pancreas in the gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3701-3703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |