Published online Jul 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i25.3020

Revised: December 21, 2010

Accepted: December 28, 2010

Published online: July 7, 2011

AIM: To evaluate the prevalence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms and their association with clinical and functional characteristics in elderly outpatients.

METHODS: The study involved 3238 outpatients ≥ 60 years consecutively enrolled by 107 general practitioners. Information on social, behavioral and demographic characteristics, function in the activities of daily living (ADL), co-morbidities and drug use were collected by a structured interview. Upper gastrointestinal symptom data were collected by the 15-items upper gastro-intestinal symptom questionnaire for the elderly, a validated diagnostic tool which includes the following five symptom clusters: (1) abdominal pain syndrome; (2) reflux syndrome; (3) indigestion syndrome; (4) bleeding; and (5) non-specific symptoms. Presence and severity of gastrointestinal symptoms were analyzed through a logistic regression model.

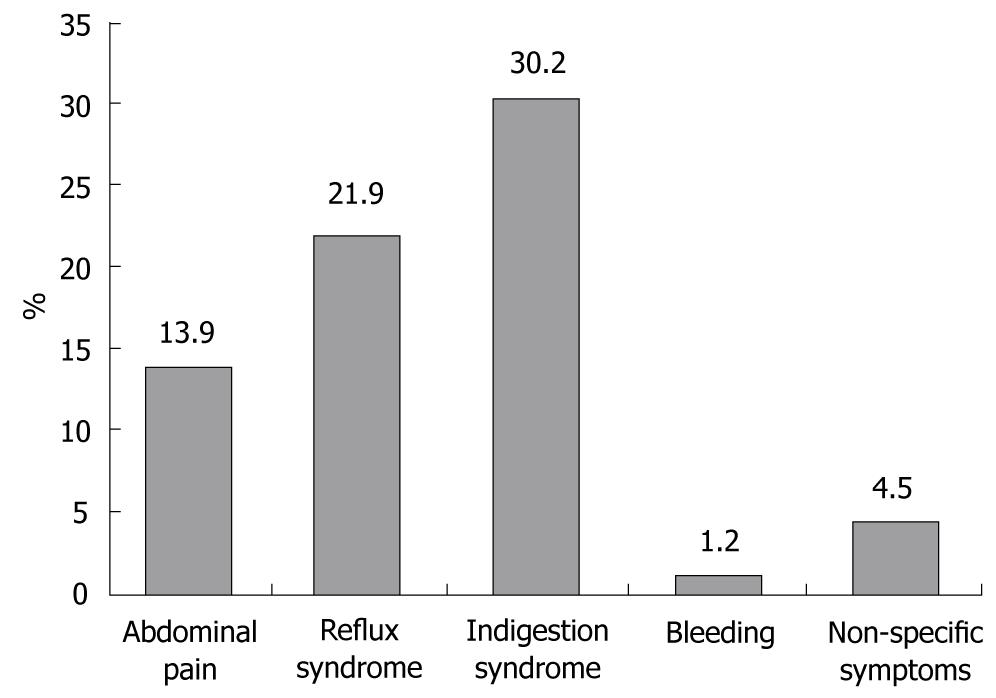

RESULTS: 3100 subjects were included in the final analysis. The overall prevalence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms was 43.0%, i.e. cluster (1) 13.9%, (2) 21.9%, (3) 30.2%, (4) 1.2%, and (5) 4.5%. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms were more frequently reported by females (P < 0.0001), with high number of co-morbidities (P < 0.0001), who were taking higher number of drugs (P < 0.0001) and needed assistance in the ADL. Logistic regression analysis demonstrated that female sex (OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.17-1.64), disability in the ADL (OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.12-1.93), smoking habit (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.00-1.65), and body mass index (OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.04-1.08), as well as the presence of upper (OR = 3.01, 95% CI: 2.52-3.60) and lower gastroenterological diseases (OR = 2.25, 95%CI: 1.70-2.97), psychiatric (OR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.28-2.01) and respiratory diseases (OR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.01-1.54) were significantly associated with the presence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms.

CONCLUSION: Functional and clinical characteristics are associated with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. A multidimensional comprehensive evaluation may be useful when approaching upper gastrointestinal symptoms in older subjects.

- Citation: Pilotto A, Maggi S, Noale M, Franceschi M, Parisi G, Crepaldi G. Association of upper gastrointestinal symptoms with functional and clinical characteristics in the elderly. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(25): 3020-3026

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i25/3020.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i25.3020

Epidemiological and clinical studies suggest that the prevalence of upper gastrointestinal diseases is particularly high in older subjects[1]. Nevertheless, in older patients the clinical identification of upper gastrointestinal diseases on the basis of the presence of symptoms is very difficult and sometimes misleading. It has been reported that older patients with upper gastrointestinal diseases, such as reflux esophagitis[2] or peptic ulcer disease[3], may report a low prevalence of typical or specific symptoms, several patients recounting only nonspecific or no symptoms at all; thus the presence of nonspecific symptoms has been reported as one of the most important reasons for late diagnoses or even severe complications in elderly patients[4,5]. Conversely, many older subjects report upper gastrointestinal symptoms without a clear relationship with well defined disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract[6]. Indeed, several clinical and functional conditions may influence the symptom perception and referral to doctor, especially in older people[7]. However, very few studies have been performed on the potential association of upper gastrointestinal symptoms and clinical and functional conditions in old age.

Recently, a diagnostic questionnaire, i.e. upper gastro-intestinal symptom questionnaire for the elderly (UGISQUE), was developed and validated in two independent populations of elderly patients who underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy[8]. The UGISQUE included 15 items grouped into five symptom clusters that comprehensively explore both specific and nonspecific symptoms of the upper gastrointestinal tract in older subjects. The findings of this study suggested the concept that the use of a comprehensive diagnostic tool specifically developed for elderly patients may be useful in reducing misleading and under-recognized diagnoses of upper gastrointestinal diseases.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms and their association with clinical and functional characteristics in a large population of elderly outpatients referred to their general practitioner (GP) by using the UGISQUE.

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients or from relatives prior to participation in the study.

The study was carried out by 107 GPs and involved elderly outpatients, in the frame of the IPOD project (Identification of symPtOms to Detect GERD and NERD). In the period between April and October 2007, 3238 patients were screened for enrollment, based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) age ≥ 60 years; (2) ability to provide an informed consent; and (3) willingness to participate to the study. Exclusion criteria were: (1) a cognitive impairment of grade moderate to severe as evaluated by a short portable mental status questionnaire (SPMSQ)[9] score ≤ 7; and (2) presence of neoplasm at late stages.

Data were obtained by a structured interview of patients and were confirmed by the GP’s medical records. General practitioners included all patients seen during a 1-wk period (5 working days) who agreed to participate in the study. All subjects aged 65 years and over who consulted their GP for a medical problem during this 2-wk period were included in the study. Elderly patients who were visited in their home or in nursing homes were not included.

The interview was carried out by skilled GPs. A Computer Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI) instrument followed the interview step by step in collecting and recording the demographic, functional and clinical data as well as the information on drug use and gastrointestinal symptoms. Computerized records were e-mailed to the statistics reference center for evaluation.

Information on socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, education), body mass index (BMI; body weight/height2), smoking status, alcohol consumption, coffee use, functional status, comorbidity and drug consumption were collected by a structured interview.

Functional status was evaluated by the Barthel Index[10], which defines the level of dependence/independence of eight daily personal care activities (Activities of Daily Living, ADL), including bathing, eating, personal hygiene, dressing, toilet use, transfer, bladder and bowel control.

The cumulative illness rating scale (CIRS)[11] was used to ascertain presence and severity (5-point ordinal scale, score 1-5) of pathology in each of 13 systems, including cardiac, vascular, respiratory, eye-ear-nose-throat, upper and lower gastroenteric disease, hepatic, renal, genito-urinal, musculo-skeletal, skin disorder, nervous system, endocrine-metabolic and psychiatric behavioral problems. In this study we have considered only the co-morbidity assessed as the number of concomitant diseases from moderate to severe levels (grade from 3 to 5). Medication use was defined according to the anatomical therapeutics chemical classification (ATC) code system[12] and the number of drugs used by patients was recorded. Patients were defined as drug users if they took a medication of any drug included in the ATC classification code system.

The UGISQUE (Table 1) includes 15 items for the description of upper gastrointestinal symptoms divided into five symptom clusters: (1) abdominal pain syndrome [1. stomach ache/pain, 2. hunger pains in stomach or belly]; (2) reflux syndrome [3. heartburn, 4. acid reflux]; (3) indigestion syndrome [5. nausea, 6. rumbling in the stomach (i.e. vibrations or noise in the stomach), 7. bloated stomach (i.e. swelling in the stomach), 8. burping (i.e. bringing up air or gas through the mouth)]; (4) bleeding [9. hematemesis, 10. melena, 11. anemia]; (5) non-specific symptoms [12. anorexia, 13. weight loss, 14. vomiting, 15. dysphagia].

| UGISQUE | Symptoms in the last week | Questions | Response scale1 | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Abdominal pain syndrome | 1 | Stomach ache or pain | Has he had pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen or the stomach? | ||||

| 2 | Hunger pains in stomach or belly | Has he had hunger pains? (an empty, hollow feeling in the stomach and the need to eat between meals) | |||||

| Reflux syndrome | 3 | Heartburn | Has he suffered from heartburn? (a nagging, burning sensation in the upper chest or retrosternal region) | ||||

| 4 | Acid reflux | Has he had acid regurgitation? (a sudden regurgitation of stomach acid content to the esophagus) | |||||

| Indigestion syndrome | 5 | Nausea | Has he suffered from nausea? (a feeling of discomfort in the stomach that can lead to vomiting) | ||||

| 6 | Rumbling in the stomach | Has he had rumbling stomach? (i.e. growling, bubbling or gurgling sounds) | |||||

| 7 | Bloated stomach | Has he suffered from bloating? (i.e. a fullness feeling correlated to gas build-up) | |||||

| 8 | Burping | Has he suffered from burping? (i.e. bringing up excessive air followed by a sense of relief) | |||||

| Bleeding | 9 | Hematemesis | Has he had hematemesis? (vomiting blood) or melena (black stools) | ||||

| 10 | Melena | ||||||

| 11 | Anemia | Loss of at least 3 g/dL of hemoglobin in the last 3 mo | |||||

| Non-specific symptoms | 12 | Anorexia | Has he suffered from anorexia? (a loss of appetite or interest in food) | ||||

| 13 | Weight loss | Has he had a weight loss? (involuntary weight loss in the last 3 mo) | |||||

| 14 | Vomiting | Has he suffered from vomiting? (involuntary, forceful expulsion of gastric content through the mouth) | |||||

| 15 | Dysphagia | Has he had dysphagia? (sensation of difficulty in passing the food bolus through the esophagus) | |||||

The UGISQUE includes a response scale with four grades: (0) absent = no symptoms are reported by patient; (1) mild = awareness of symptoms, but they are easily tolerated; (2) moderate = symptoms interfering with the normal activities; and (3) severe = symptoms that induce inability to perform normal activities or symptoms requiring health intervention. Symptomatic patients were defined as those patients who reported moderate or severe discomfort in at least one item. The recall period for symptom assessment was the last week before the interview.

Further details of the UGISQUE methods have been reported elsewhere[8].

Subjects were classified according to the absence/presence of UGISQUE symptoms into two groups. Associations between the two groups of subjects and demographic and clinical characteristics were investigated using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Group mean values were compared through the generalized linear model procedure, after testing for homoschedasticity with the Levene’s test; Welch’s Anova was considered in case of heteroschedasticity.

A logistic regression model was then developed. The variable on presence of UGISQUE symptoms was considered as the dependent variable, dichotomized into “no symptoms”vs“moderate/severe symptoms”. As possible predictors, demographic (sex; age; marital status; education), clinical (comorbidities; drug use; BMI; smoking status; alcohol and coffee consumption) and functional (need of assistance in the ADL) characteristics were selected through a stepwise procedure. Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to estimate the association of covariates with the dependent variable.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.1.3 package (Cary, SAS Institute).

During the study period 3238 patients were screened for enrollment; 138 patients were excluded because they did not have valid data on UGISQUE. Thus, complete data on 3100 patients were included in the present analysis: 1547 men, 1553 women; with a mean age of 72.2 ± 7.0 years, and an age range of 60-96 years.

Figure 1 shows the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, according to the five UGISQUE clusters. The overall prevalence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms was 43.0% (1332 subjects out of 3100). In detail, 13.9% of subjects reported symptoms of abdominal pain, 21.9% reported symptoms of reflux syndrome, 30.2% of subjects reported symptoms of indigestion syndrome, 1.2% of subjects reported bleeding symptoms and 4.5% of subjects reported non-specific symptoms.

Table 2 reports the demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects, stratified by the two study groups. No significant differences were found between the two groups in mean age, education and in the prevalence of smoking habit, alcohol and coffee consumption. In symptomatic subjects, a significantly higher prevalence of women (P < 0.0001) and unmarried subjects (P = 0.0185) was found compared to asymptomatic subjects. In the symptomatic group, a significantly higher prevalence of subjects who needed assistance in the ADL than in the asymptomatic subjects was observed (21.5% vs 14.2%, P < 0.0001). Moreover, symptomatic subjects had higher prevalence (P < 0.0001) and mean number (P < 0.0001) of concomitant diseases, higher prevalence of drug consumption (P = 0.0285) and higher mean number of drugs taken (P < 0.0001) than asymptomatic subjects.

| No symptoms (n = 1768) | Yes symptoms (n = 1332) | P-value | |

| Sex (females, %) | 45.8 | 55.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 72.2 ± 7.0 | 72.2 ± 6.9 | 0.8635 |

| Marital status (married, %) | 68.3 | 64.2 | 0.0185 |

| Education (none/primary school, %) | 75.8 | 78 | 0.1503 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 26.0 ± 3.6 | 26.6 ± 3.9 | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking status (current smoker, %) | 11.2 | 13 | 0.1288 |

| Alcohol consumption (%) | 45.7 | 42.6 | 0.0957 |

| Coffee consumption (%) | 85.1 | 87.3 | 0.0743 |

| Heart diseases (%) | 29.3 | 33.2 | 0.0198 |

| Hypertension (%) | 63.2 | 65.3 | 0.2274 |

| Vascular diseases (%) | 13.6 | 16.6 | 0.0223 |

| Respiratory diseases (%) | 15.3 | 22.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Eye-ear-nose-throat diseases (%) | 13.6 | 14.9 | 0.3103 |

| Upper gastroenterological diseases (%) | 20 | 44.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Lower gastroenterological diseases (%) | 6.6 | 14.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Hepatic diseases (%) | 5.6 | 8.1 | 0.0046 |

| Kidney diseases (%) | 4.5 | 5 | 0.4692 |

| Genital-urinary diseases (%) | 24.7 | 26.6 | 0.2434 |

| Skeletal, muscle, skin diseases (%) | 43.4 | 50.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Nervous system diseases (%) | 5.3 | 6.5 | 0.1351 |

| Endocrine-metabolic diseases (%) | 22.5 | 22 | 0.7617 |

| Psychiatric diseases (%) | 12.6 | 21.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Number of comorbidities (mean ± SD) | 2.8 ± 1.7 | 3.5 ± 1.9 | < 0.0001 |

| 4 or more comorbidities (%) | 28.7 | 45.3 | < 0.0001 |

| Drug consumption (%) | 91.7 | 93.8 | 0.0285 |

| Number of drugs (mean ± SD) | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 3.3 ± 1.7 | < 0.0001 |

| 3 or more drugs (%) | 52.5 | 64 | < 0.0001 |

| Need of assistance in activities of daily living (%) | 14.2 | 21.5 | < 0.0001 |

As regards the concomitant diseases, 45.3% of symptomatic subjects reported 4 or more comorbidities, with respect to 28.7% among asymptomatic subjects (P < 0.0001). Moreover, higher prevalence rates of heart diseases, vascular, respiratory, upper and lower gastroenterological, hepatic, skeletal-muscle-skin and psychiatric diseases were observed in subjects who reported upper gastrointestinal symptoms than asymptomatic subjects.

Table 3 shows the results of a stepwise selection on a logistic regression model, with outcome as to the presence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms according to the UGISQUE clusters. Significant risk factors for upper gastrointestinal symptoms were female gender (OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.17-1.64), need of assistance in the ADL (OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.12-1.93), actual smoking (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.00-1.65) and BMI (OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.04-1.08).

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Sex (female) | 1.39 | 1.17-1.64 | < 0.0001 |

| Respiratory disease | 1.25 | 1.01-1.54 | 0.0430 |

| Upper gastroenterological diseases | 3.01 | 2.52-3.60 | < 0.0001 |

| Lower gastroenterological diseases | 2.25 | 1.70-2.97 | < 0.0001 |

| Psychiatric diseases | 1.60 | 1.28-2.01 | < 0.0001 |

| Need of assistance in activities of daily living | 1.47 | 1.12-1.93 | 0.0057 |

| Smoking status (actual smoker) | 1.29 | 1.00-1.65 | 0.0476 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.06 | 1.04-1.08 | < 0.0001 |

As expected, subjects with upper (OR = 3.01, 95% CI: 2.52-3.60) and lower gastrointestinal diseases (OR = 2.25, 95% CI: 1.70-2.97) were three and two times, respectively, more likely to report upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Moreover, the presence of psychiatric diseases (OR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.28-2.01) and respiratory diseases (OR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.01-1.54) were also significant predictors for upper gastrointestinal symptoms according to the UGISQUE clusters.

This study reports the results of a wide survey of the prevalence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms and their association with clinical and functional characteristics in a large population of elderly outpatients. The results showed that demographic, behavioral, functional and clinical characteristics of subjects were significantly associated with the presence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in old age. These findings suggest that a comprehensive clinical and functional evaluation may be useful in approaching upper gastrointestinal symptoms in older subjects.

The mean age of the IPOD sample was not significantly different from the mean age of the Italian population who were 60-96 years old, as reported by ISTAT for 2006 (72.2 ± 7.0 years vs 72.1 ± 10.8 years, respectively; t = 0.7204, P = 0.4713) [13].

Co-morbidity data, assessed by the CIRS, shows a population that is affected by pathologies in 97.2% of cases, of whom 35.4% reported 4 or more comorbidities. In agreement with previous studies in geriatric populations[14,15], the most frequent diseases were hypertension (63.9%), bone and joint diseases (45.8%), heart diseases (30.7%) and diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract (30.8%). The high prevalence of comorbidities also reflects the wide use of drugs found in this population. In fact, 92.1% of subjects took at least one drug, with 57.2% of the subjects taking 3 or more. This high prevalence of drug consumption is in agreement with other Italian[16,17] and American studies[18], that have reported drug use prevalence ranging from 90% to 96% in older outpatient populations.

In this study, the cognitive state of subjects was assessed to exclude people who were unable to respond appropriately to the UGISQUE questionnaire. Thus, by excluding subjects with moderate and/or severe cognitive impairment, only 17% of subjects included in the study reported needing assistance in one or more items of ADL. These findings are in agreement with previous data from the Italian national multicenter study of the SOFIA project[16].

In this study we used the UGISQUE, a recently developed questionnaire for the collection of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in elderly patients who underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Findings from this study suggest that UGISQUE may also be a clinically useful diagnostic tool for evaluating upper gastrointestinal symptoms in elderly outpatients. Indeed, the survey demonstrates that more than 43% of subjects reported at least one symptom of the upper gastrointestinal tract, i.e. 13.9% of subjects reporting abdominal pain, 21.9% reflux symptoms, 30.2% indigestion symptoms, 1.2% bleeding symptoms and 4.5% non-specific symptoms of anemia (1%), dysphagia (2.7%) and vomiting (0.4%). The presence of this last cluster of symptoms seems to reflect a peculiarity of clinical presentation of the upper gastrointestinal disorders in elderly subjects, as previously reported in endoscopic studies carried out in older populations[2-5] and in agreement with previous data from Italy[19] and Europe[20,21].

Logistic regression demonstrated that female gender was a significant risk factor for reporting upper gastrointestinal symptoms; this finding is in agreement with previous studies performed in general populations[22]. Moreover, disability in the ADL was a significant predictor of upper gastrointestinal symptoms. All these findings confirm a previous study[16], performed in 5500 elderly outpatients, that reported a significantly higher prevalence of symptoms in females, patients who were taking a higher number of drugs, and those who had higher disability.

In agreement with previous studies that reported a significant association between high BMI value and gastrointestinal disorders in young populations[23-25], in this present study, for the first time, we also observed such an association between BMI and upper gastrointestinal symptoms in elderly people. Indeed, changes in gastroesophageal anatomy and physiology caused by obesity, including a diminished lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure, the development of a hiatal hernia, and increased intragastric pressure[26], may explain this association.

As expected, the presence of gastroenterological diseases was significantly associated with the risk of presenting upper gastrointestinal symptoms according to the UGISQUE clusters. Very interestingly, however, the presence of psychiatric disorders as well as respiratory diseases was also significantly associated with the presence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in this population. While it has been reported that psychological distress, depression and anxiety may provoke symptoms of many organ systems, including upper gastrointestinal symptoms that prompt patients to consult a physician[27], at present, this seems to be the first study that has reported such an association in older subjects. This finding is in agreement with previous data reporting a significant association of upper gastrointestinal symptoms with the use of psycholeptic drugs (88% of which were benzodiazepines) in elderly outpatients[16] and supports the concept that subjects with anxiety syndromes and sleep disturbances may have a greater frequency of functional gastrointestinal disorders, including abdominal pain and/or indigestion syndrome[28]. As regards the significant association between upper gastrointestinal symptoms and respiratory diseases, data do exist that suggest a pathophysiological[29] and clinical[30] link between upper gastrointestinal symptoms and respiratory diseases, especially asthma[31] and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[32]. The data are in agreement also with a previous finding of a higher use of selective β2 adrenoreceptor/adrenergic agonist drugs in older subjects with upper gastrointestinal symptoms than in asymptomatic subjects[16].

All these findings suggest that investigation of psychological and/or respiratory problems may be helpful for elderly patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms.

In conclusion, demographic, functional and clinical characteristics of patients are significantly associated with the presence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in old age. These findings suggest that a comprehensive clinical and functional evaluation may be useful in approaching upper gastrointestinal symptoms in older subjects.

Epidemiological and clinical studies suggest that the prevalence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms is particularly high in older age. However, very few studies have been performed on the potential association of upper gastrointestinal symptoms and clinical and functional conditions in old age. Recently, the upper gastroIntestinal symptom questionnaire for the elderly (UGISQUE) was developed and validated in different populations of elderly patients who underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are widely diffused and frequently misdiagnosed in the elderly population. Their impact on clinical and functional conditions may influence the performance in the activities of daily living, therapeutic compliance, nutrition status, and finally, the quality of life. A multidimensional approach may improve clinical and functional evaluation of the older patient with gastrointestinal symptoms to better identify therapeutic and health care programs.

Specific functional and clinical characteristics, such as disability in the activities of daily living (ADL), body mass index and the presence of gastroenterological, psychiatric and respiratory diseases, are significantly associated with the presence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in older patients. A comprehensive clinical and functional evaluation by means of diagnostic tools specific for older people (ADL, UGISQUE) may be useful in approaching upper gastrointestinal symptoms in older subjects

The functional and clinical definition of older patients with gastrointestinal symptoms could lead to better care in clinical practice. The UGISQUE is easy to administer and effective in predicting gastrointestinal disorders in older patients. Further prospective studies on the application of the UGISQUE for predicting gastrointestinal adverse drug reactions and other adverse outcomes, such as disability in the activities of daily living, are needed to evaluate the role of a multidimensional approach in improving the care of older patients.

This cross-sectional study analyzed relationships of upper gastrointestinal symptoms and functional or clinical characteristics in elderly outpatients. This manuscript is well-written.

Peer reviewer: Shogo Kikuchi, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Public Health, Aichi Medical University School of Medicine, 21 Karimata, Yazako, Nagakute-cho, Aichi-gun, Aichi, 480-1195, Japan

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Crane SJ, Talley NJ. Chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007;23:721-734. |

| 2. | Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Leandro G, Scarcelli C, D'Ambrosio LP, Seripa D, Perri F, Niro V, Paris F, Andriulli A. Clinical features of reflux esophagitis in older people: a study of 840 consecutive patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1537-1542. |

| 3. | Hilton D, Iman N, Burke GJ, Moore A, O'Mara G, Signorini D, Lyons D, Banerjee AK, Clinch D. Absence of abdominal pain in older persons with endoscopic ulcers: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:380-384. |

| 4. | Maekawa T, Kinoshita Y, Okada A, Fukui H, Waki S, Hassan S, Matsushima Y, Kawanami C, Kishi K, Chiba T. Relationship between severity and symptoms of reflux oesophagitis in elderly patients in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:927-930. |

| 5. | Seinelä L, Ahvenainen J. Peptic ulcer in the very old patients. Gerontology. 2000;46:271-275. |

| 6. | Wallace MB, Durkalski VL, Vaughan J, Palesch YY, Libby ED, Jowell PS, Nickl NJ, Schutz SM, Leung JW, Cotton PB. Age and alarm symptoms do not predict endoscopic findings among patients with dyspepsia: a multicentre database study. Gut. 2001;49:29-34. |

| 7. | Pilotto A, Addante F, D'Onofrio G, Sancarlo D, Ferrucci L. The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and the multidimensional approach. A new look at the older patient with gastroenterological disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:829-837. |

| 8. | Pilotto A, Maggi S, Noale M, Franceschi M, Parisi G, Crepaldi G. Development and validation of a new questionnaire for the evaluation of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly population: a multicenter study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:174-178. |

| 9. | Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23:433-441. |

| 10. | Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61-65. |

| 11. | Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16:622-626. |

| 12. | Available from: http://www.whocc.no/atcddd/ [Access 12/2007]. |

| 13. | Available from: http://demo.istat.it/. |

| 14. | Prevalence of chronic diseases in older Italians: comparing self-reported and clinical diagnoses. The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging Working Group. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:995-1002. |

| 15. | Karlamangla A, Tinetti M, Guralnik J, Studenski S, Wetle T, Reuben D. Comorbidity in older adults: nosology of impairment, diseases, and conditions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:296-300. |

| 16. | Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Vitale D, Zaninelli A, Masotti G, Rengo F. Drug use by the elderly in general practice: effects on upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:65-73. |

| 17. | Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Leandro G, Di Mario F. NSAID and aspirin use by the elderly in general practice: effect on gastrointestinal symptoms and therapies. Drugs Aging. 2003;20:701-710. |

| 18. | Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Rosenberg L, Anderson TE, Mitchell AA. Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States: the Slone survey. JAMA. 2002;287:337-344. |

| 19. | Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Vitale DF, Zaninelli A, Masotti G, Rengo F. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms and therapies in elderly out-patients, users of non-selective NSAIDs or coxibs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:147-155. |

| 21. | Diaz-Rubio M, Moreno-Elola-Olaso C, Rey E, Locke GR 3rd, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux: prevalence, severity, duration and associated factors in a Spanish population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:95-105. |

| 22. | Tougas G, Chen Y, Hwang P, Liu MM, Eggleston A. Prevalence and impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the Canadian population: findings from the DIGEST study. Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2845-2854. |

| 23. | Talley NJ, Quan C, Jones MP, Horowitz M. Association of upper and lower gastrointestinal tract symptoms with body mass index in an Australian cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:413-419. |

| 24. | Talley NJ, Howell S, Poulton R. Obesity and chronic gastrointestinal tract symptoms in young adults: a birth cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1807-1814. |

| 25. | Delgado-Aros S, Locke GR 3rd, Camilleri M, Talley NJ, Fett S, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Obesity is associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal symptoms: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1801-1806. |

| 26. | Friedenberg FK, Xanthopoulos M, Foster GD, Richter JE. The association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2111-2122. |

| 27. | Bröker LE, Hurenkamp GJ, ter Riet G, Schellevis FG, Grundmeijer HG, van Weert HC. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms, psychosocial co-morbidity and health care seeking in general practice: population based case control study. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:63. |

| 28. | Vege SS, Locke GR 3rd, Weaver AL, Farmer SA, Melton LJ 3rd, Talley NJ. Functional gastrointestinal disorders among people with sleep disturbances: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1501-1506. |

| 29. | Stein MR. Possible mechanisms of influence of esophageal acid on airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Med. 2003;115 Suppl 3A:55S-59S. |

| 30. | Räihä IJ, Ivaska K, Sourander LB. Pulmonary function in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease of elderly people. Age Ageing. 1992;21:368-373. |