Published online Jun 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i21.2641

Revised: September 25, 2010

Accepted: October 2, 2010

Published online: June 7, 2011

AIM: To evaluate the possible relationship between varicocele and chronic constipation.

METHODS: Between April 2009 and May 2010, a total of 135 patients with varicocele or constipation and 120 healthy controls were evaluated. Patients were divided into two groups. In both groups detailed medical history was taken and all patients were examined physically by the same urologist and gastroenterologist. All of them were evaluated by color Doppler ultrasonography. All patients with constipation, except for the healthy controls of the second group, underwent a colonoscopy to identify the etiology of the constipation. In the first group, we determined the rate of chronic constipation in patients with varicocele and in the second group, the rate of varicocele in patients with chronic constipation. In both groups, the rate of the disease was compared with age-matched healthy controls. In the second group, the results of colonoscopies in the patients with chronic constipations were also evaluated.

RESULTS: In the first group, mean age of the study and control groups were 22.9 ± 4.47 and 21.8 ± 7.21 years, respectively (P < 0.05). In the second group, mean age of the study and control groups were 52.8 ± 33.3 and 51.7 ± 54.3 years, respectively (P < 0.05). In the first group, chronic constipation was observed in 8 of the 69 patients with varicocele (11.6%) and 3 out of 60 in healthy controls (5%), respectively. In this regard, there was no statistical significance between varicocele patients and the healthy control (P = 0.37). In the second group, varicocele was observed in 16 of the 66 patients with chronic constipation (24.24%) and 12 out of 60 in healthy controls (20%) respectively. Similarly, there was no statistical significance between chronic constipation and healthy controls (P = 0.72). Internal/external hemorrhoids were detected in 4 of the 16 patients with chronic constipation and varicocele, in the second group. In the remaining 50 patients with chronic constipation 9 had internal/external hemorrhoids. In this regard, there was no statistical significance between chronic constipation and healthy controls (P = 0.80).

CONCLUSION: Chronic constipation may not be a major predictive factor for the development of varicocele, but it may be a facilitator factor for varicocele.

- Citation: Kilciler G, Sancaktutar AA, Avcı A, Kilciler M, Kaya E, Dayanc M. Chronic constipation: Facilitator factor for development of varicocele. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(21): 2641-2645

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i21/2641.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i21.2641

Varicocele, the most common surgically correctible cause of male infertility, is characterized as abnormal tortuosity and dilation of the pampiniform plexus within the spermatic cord[1]. Although the exact etiology of varicocele is not known[2], the pathogenesis may be associated with various factors resulting in increased retrograde blood flow or increased pressure in the pampiniform plexus and internal spermatic vein[3].

Constipation is a common, often chronic, gastrointestinal motility disorder described by such symptoms as straining, difficult stool, and infrequent defecation[4]. The prevalence in children ranges from 0.7% to 30%. In adults, constipation affects between 2% and 28% of the general population[5].

In this study we aimed to evaluate the possible relationship between varicocele and chronic constipation.

Between April 2009 and May 2010, a total of 135 patients with varicocele or constipation and 120 healthy controls were evaluated. Patients were divided into two groups.

The first group was consisted of 69 patients with left varicocele and 60 age-matched healthy volunteers, and the second group was consisted of 66 patients with chronic constipation and 60 age-matched healthy volunteers.

Patients who were admitted to the outpatient clinic with complaints of scrotal pain and/or infertility were requited in the first group. In this group, the age-matched healthy controls were the people who were admitted to the outpatient clinic with no varicocele.

In the second group, patients diagnosed with chronic constipation by a gastroenterologist were consulted to the urology outpatient clinic and examined for varicocele. The age-matched healthy controls were the people who were admitted to the outpatient gastroenterology clinic with no constipation.

In both groups a detailed medical history was taken and all patients were examined physically by the same urologist and gastroenterologist in attention to those associated with varicocele and constipation. Afterwards, all of them underwent a standard gray scale and color Doppler ultrasonographic examination of the scrotum, which was performed by the same radiologist. For the ultrasonographic examination, a color Doppler scanner (GE Logic 9, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) equipped with a 5- to 10-MHz linear transducer was used. The transverse diameter of the biggest vein in the pampiniform plexus was measured 3 times by a transducer probe with a frequency of 7.5-10 MHz during normal breathing, and the Valsalva maneuver. The arithmetic mean value of the diameters measured was used for the assessment. Patients with a varicose spermatic vein larger than 2.0 mm or having reversal flow during the Valsalva maneuver were included in the study group as a varicocele patient.

In the second group, patients were included according to the scope of the Rome III criteria. The Rome III criteria system was developed to classify functional gastrointestinal disorders based on clinical symptoms.

In this regard, patients who had straining and incomplete evacuation and hard stools more than 25% of the time, as well fewer than 3 bowel actions in a week were defined as “chronically constipated”. The patients were questioned in terms of systemic diseases and other medications. Anal tonometry was performed to assess the colonic transit time. Colonoscopy and anoscopy was performed in the same session. The presence of hemorrhoid was confirmed. The patients in whom no reason for constipation was detected by colonic transit, anorectal manometry, anoscopy or colonoscopy studies, were enrolled in the study. The hemorrhoid was diagnosed by anoscopy. The other studies were performed for the other etiologies except hemorrhoids. The control group of Group-2 consisted of patients who underwent colonoscopy because of gastrointestinal symptoms other than constipation. All colonoscopies were performed by the same gastroenterologist with a Olympus Q160 AL 160 cm video colonoscope. During the colonoscopy 4 mg midazolam were given to all the patients for anesthesia.

Patients with drug use such as diuretics, hypotensive drugs, anticonvulsants anal fistulas and abscesses, and neurogenic and endocrine disorders associated with constipation such as paraplegia and hypothyroidism, were excluded. Due to the possible effects to spermatic veins, patients with a past medical history of inguinal or scrotal surgery were excluded from the study.

In the first group, we determined the rate of chronic constipation in patients with varicocele and in the second group, the rate of varicocele in patients with chronic constipation. In both groups, the rates of these diseases were compared with age-matched healthy controls. In the second group, the results of colonoscopies in the patients with chronic constipations were also evaluated.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by the local Ethical Committee.

SPSS for Windows Version 15 was used for statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was based on χ2 test. Results are reported as mean ± SD where P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

In the first group, mean age of the study and control groups were 22.9 ± 4.47 and 21.8 ± 7.21 years, respectively. There was no statistical significance between the mean ages of the study and control groups (P = 0.83).

In the second group, mean age of the study and control groups were 52.8 ± 33.3 and 51.7 ± 54.3 years, respectively. There was no statistical significance between the mean ages of the study and control groups (P = 0.78).

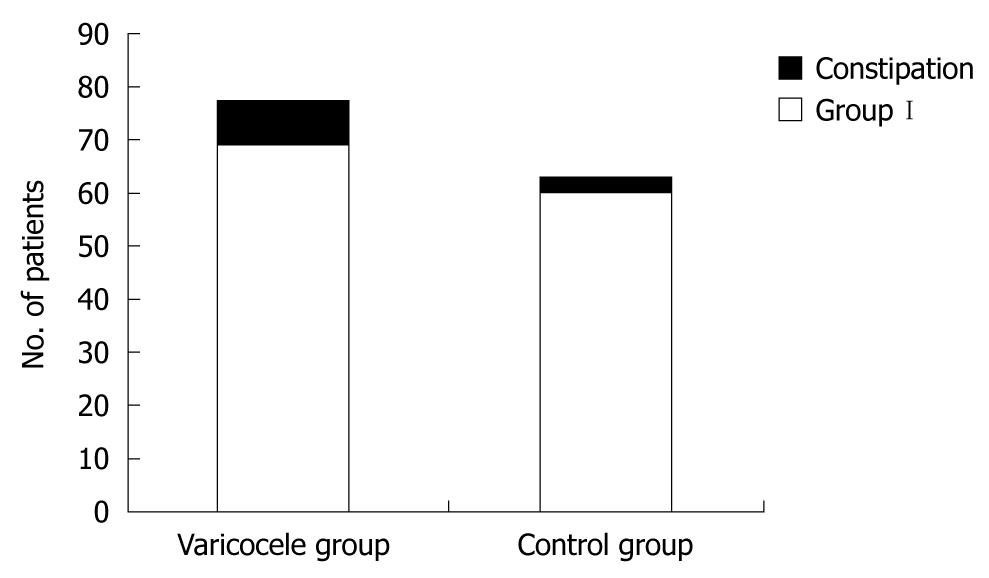

In the first group, chronic constipation were observed in 8 of the 69 patients with varicocele (11.6%) and 3 of the 60 in healthy controls (5%), respectively. In this regard, there was no statistical significance between varicocele patients and healthy control (P = 0.37) (Table 1 and Figure 1).

| Group | Varicocele group (n = 69) | Control group (n = 60) | P value |

| Constipation | |||

| (+) | 8 | 3 | |

| (-) | 61 | 57 | 0.37 |

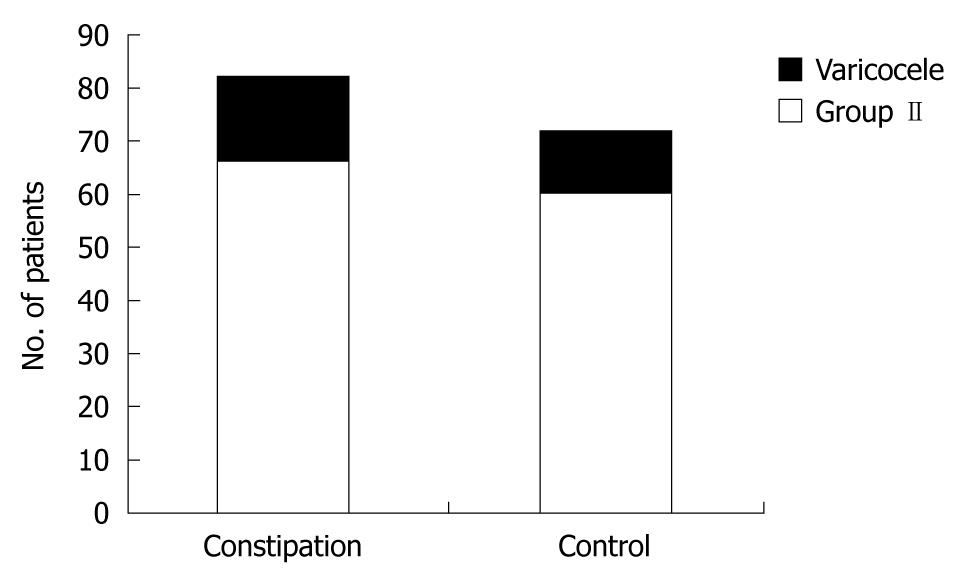

In the second group, varicocele was observed in 16 of the 66 patients with chronic constipation (24.24%) and 12 of the 60 in healthy controls (20%) respectively. Again, there was no statistical significance between chronic constipation and healthy controls (P = 0.72) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

| Group | Constipation group (n = 66) | Control group (n = 60) | P value |

| Varicocele | |||

| (+) | 16 | 12 | |

| (-) | 50 | 48 | 0.72 |

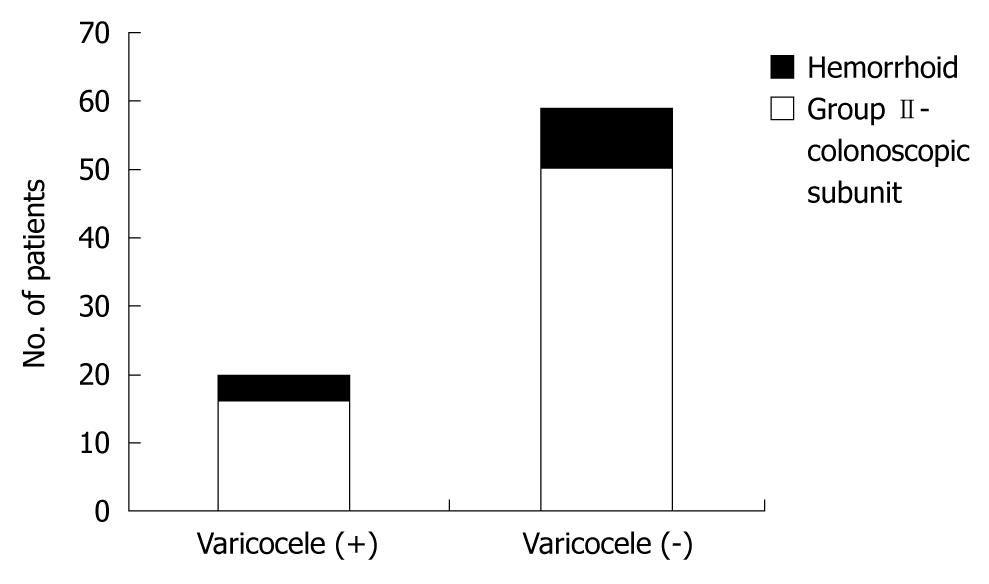

Internal/external hemorrhoids were detected in 4 of the 16 patients with chronic constipation and varicocele, in the second group. In the remaining 50 patients with chronic constipation 9 had internal/external hemorrhoids. In this regard, there was no statistical significance between chronic constipation and healthy controls (P = 0.80). Total colonoscopy findings in the second group is summarized in Table 3 and Figure 3.

| Patients with chronic constipation (n = 66) | Varicocele (+) (n = 16) | Varicocele (-) (n = 50) | P value |

| Colonoscopy findings | |||

| Hemorrhoid | 4 | 9 | |

| Other intestinal pathologies | - | 24 | |

| Normal | 12 | 17 | 0.8 |

No complication was observed during the colonoscopy procedure.

Varicocele, which is defined as the dilatation of veins of pampiniform venous plexus, is found in approximately 15% of the general population, 35% of men with primary infertility and 80% of men with secondary infertility[6].

Although the exact etiology has not been identified yet, several mechanisms have been proposed in the pathophysiology of varicocele involving insufficiency or absence of venous valves[6], anatomic inclination due to raised pressure in the left renal vein[7], “nut-cracker” phenomenon due to compression of left renal vein between aorta and superior mesenteric artery and oxidative stress[8].

Constipation may be clarified as having two of the following symptoms of straining, difficult stools, sensation of incomplete discharging, sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage, requiring manual maneuvers to evacuate the stools, and having less than 3 evacuations per week using the Rome III criteria[9]. For the constipation to be described as chronic, the Rome criteria need to have been met for the previous 3 mo, with the attack of symptoms 6 mo prior to diagnosis[10]. In our study the group was formed by patients with symptoms of constipation for at least 8 wk. A longer follow-up period is needed to evaluate the relationship between the duration of constipation and varicocele. Therefore; in this study, the relation of the duration of constipation and varicocele was not investigated. This issue may to be another subject of study.

Several mechanisms have been proposed for the physiopathologic mechanism of chronic constipation, but the following 2 major disturbances are commonly accepted as related to the development of constipation: “colonic inertia”[4], causing a delay in the passage of the fecal material through the colon; and “outlet inertia” or “anorectal dysfunction”[11], by which the defecatory mechanism is disturbed, causing difficulty in ejected stool from the distal colon to the anus[12].

In the literature on the urinary tract abnormalities and constipation are extensive. The first study reported[13] that 31% of children with functional constipation had megaureter, and then they recommended that the cause would be a mechanical pressure phenomenon. Afterwards, several authors linked constipation to dysfunctional voiding patterns[14-16]. Moreover, higher rates of dilatation of the upper urinary tract and urinary tract infections in constipated patients were showed in some studies[14,15]. These results were ascribed to mechanical compression of the urinary tract by the distended rectum, due the anatomic proximity of the bladder and urethra to the rectum[16]. Also, constipation in children was showed by Fein et al[17] as a cause of scrotal or testicular pain, which was ascribed to direct neural stimulation by a fecal mass in the rectum. In this regard, the posterior sacral nerve, ilioinguinal nerve, or genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve has been involved in this neural association[18].

To our knowledge, there is only one study in the literature which investigates the prevalence of chronic constipation in patients with varicocele. According to this study, varicocele was determined in almost 50% of patients with chronic constipation which is suggested to be an important causative factor for the development of left varicocele[19]. The authors demonstrated the statistically significant relationship between the chronic constipation and varicocele, and had proposed a routine ultrasonographic evaluation for the possible development of varicocele in men who have pain or who are otherwise symptomatic[19]. Our study will be the second in the literature demonstrating the relationship between chronic constipation and varicocele.

Generally, the incidence of chronic constipation is reported as 3% in the young population[20]. In the first group of our study, chronic constipation rates were 5% and 11% in the control group and varicocele patients, respectively. These rates may support the relationship between the urinary tract and intestinal system[13-15].

Varicocele may be associated with underlying venous pathological conditions[7]. A study proved that a left varicocele may be two sides disease caused by an inadequacy of the one-way valves in the internal spermatic veins, connected to persistent pathological hydrostatic pressure in the long vertical spermatic veins and venous by passes[21]. Another researcher has been explained that patients with coronary artery ectasia had an increased prevalence of varicocele compared with coronary artery disease[22]. Also, the increased prevalence of peripheral varicose veins has been reported with coronary artery ectasia by Androulakis et al[23]. Lately, Koyuncu et al[24] have shown that the rate of saphenofemoral insufficiency has been found to be statistically higher in patients with primary varicocele, compared to healthy men. In addition, many of the studies in the literature have shown a close relationship among varicocele, hemorrhoid and venous diseases[25-27]. This relationship suggests that etiopathogenesis of varicocele and hemorrhoids may be a common venous pathology[28]. According to our colonoscopies results, hemorrhoids were found in 25% of patients with varicocele and 18% of patients with no varicocele. As a result, the rational relationship between varicocele and hemorrhoid was similar within the literature. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the relationship between varicocele and chronic constipation by detailing the colonoscopic findings.

Varicocele may be attributable principally to the accompanying distention of the sigmoid colon and distal part of the descending colon, with resultant compression of the left testicular vein in the retroperitoneum, as well as repeated increased intra-abdominal pressure due to chronic straining[19].

In the literature, it has been shown that the incidence of varicocele is 9% at the second decades, 15% at the third decades and 18% at the fourth decades[25]. Contrary to these, we showed that the incidence of varicocele is 24% at the fourth decades in which the chronic constipation is seen more frequently. Therefore, this finding may support the possible relation between the intestinal system and urinary tract.

We anticipate three possible mechanisms for the relation between varicocele and chronic constipation: (1) Anatomic inclination may become more prominent with chronic constipation through the pressure effect to the intra-abdominal organs; (2) Recurrent and abrupt increases in pressure, chronic constipation may cause compression of intra-abdominal organs, eventually contributing to the development of “nutcracker” phenomenon of left renal vein by superior mesenteric artery and aorta; and (3) Chronic constipation may increase oxidative stress with hypoxic attacks and compression of venous return leading to varicocele.

In conclusion, chronic constipation may facilitate the development of varicocele with abrupt recurrent increases in intra-abdominal pressure through mechanisms of compression in intra-abdominal organs and increasing oxidative stress.

However, our study has two limitations. The first is that the number of patients in the study group may be accepted as a limited number and so, in our opinion, these findings should be confirmed with larger series. The other limitation of our study is the difference by means of patient age. The patients group’s age should be homogeneous.

In conclusion, there is a rational relationship between varicocele and chronic constipation. However there was no statistical significance between chronic constipation and varicocele. Therefore, chronic constipation may not be a major predictive factor for the development of varicocele, but it may be a facilitator factor for varicocele. The results of this hypothesis should be confirmed in larger series.

This study is interesting because there is not much written in literature. Varicocele can cause infertility in men. The etiology of varicocele is still not clear. Chronic constipation is probably a cause of male infertility.

The study is preliminary working. The duration of constipation associated with varicocele have not been evaluated in this study. This study should be supported in infertile male patients.

To our knowledge, there is only one study in the literature to investigate the prevalence of chronic constipation in patients with varicocele. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the relationship between varicocele and chronic constipation by detailing the colonoscopic findings. Chronic constipation may trigger the development of varicocele. Therefore, defecation habits of patients with male infertility should be asked.

Scrotum should be examined in male patients with chronic constipation.

Specific terminology was not used in this article.

This study is interesting because there is not much written in literature.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Paulino Martínez Hernández Magro, Department of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Hospital San José de Celaya, Eje Vial Norponiente No 200-509, Colonia Villas de la Hacienda, 38010 Celaya, Mexico; Dr. Vui Heng Chong, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Department of Medicine, Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha Hospital, Bandar Seri Begawan BA 1710, Brunei Darussalam

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Rutherford A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | French DB, Desai NR, Agarwal A. Varicocele repair: does it still have a role in infertility treatment? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20:269-274. |

| 2. | Fretz PC, Sandlow JI. Varicocele: current concepts in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:921-937. |

| 3. | Graif M, Hauser R, Hirshebein A, Botchan A, Kessler A, Yabetz H. Varicocele and the testicular-renal venous route: hemodynamic Doppler sonographic investigation. J Ultrasound Med. 2000;19:627-631. |

| 4. | Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:750-759. |

| 5. | Cook IJ, Talley NJ, Benninga MA, Rao SS, Scott SM. Chronic constipation: overview and challenges. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21 Suppl 2:1-8. |

| 6. | Sayfan J, Halevy A, Oland J, Nathan H. Varicocele and left renal vein compression. Fertil Steril. 1984;41:411-417. |

| 7. | Karadeniz-Bilgili MY, Basar H, Simsir I, Unal B, Batislam E. Assessment of sapheno-femoral junction continence in patients with primary adolescent varicocoele. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:603-606. |

| 8. | Mostafa T, Anis TH, Ghazi S, El-Nashar AR, Imam H, Osman IA. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants relationship in the internal spermatic vein blood of infertile men with varicocele. Asian J Androl. 2006;8:451-454. |

| 9. | Brugh VM, Matschke HM, Lipshultz LI. Male factor infertility. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32:689-707. |

| 10. | Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: New standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:237-241. |

| 11. | Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Clinical epidemiology of chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:525-536. |

| 13. | Kottmeier PK, Clatworthy HW. Aganglionic and functional megacolon in children--a diagnostic dilemma. Pediatrics. 1965;36:572-582. |

| 14. | Loening-Baucke V. Urinary incontinence and urinary tract infection and their resolution with treatment of chronic constipation of childhood. Pediatrics. 1997;100:228-232. |

| 15. | Dohil R, Roberts E, Jones KV, Jenkins HR. Constipation and reversible urinary tract abnormalities. Arch Dis Child. 1994;70:56-57. |

| 16. | O’Regan S, Schick E, Hamburger B, Yazbeck S. Constipation associated with vesicoureteral reflux. Urology. 1986;28:394-396. |

| 17. | Fein JA, Donoghue AJ, Canning DA. Constipation as a cause of scrotal pain in children. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:290-292. |

| 18. | Ness TJ, Metcalf AM, Gebhart GF. A psychophysiological study in humans using phasic colonic distension as a noxious visceral stimulus. Pain. 1990;43:377-386. |

| 19. | Turgut AT, Ozden E, Koşar P, Koşar U, Cakal B, Karabulut A. Chronic constipation as a causative factor for development of varicocele in men: a prospective ultrasonographic study. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:5-10. |

| 20. | Thompson WG, Heaton KW. Functional bowel disorders in apparently healthy people. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:283-288. |

| 21. | Yetkin E, Waltenberger J. Re: Is varicocele associated with underlying venous abnormalities? Varicocele and the prostatic venous plexus: H. Sakamoto and Y. Ogawa J Urol 2008; 180: 1427-1431. J Urol. 2009;181:1963; author reply 1963-1964. |

| 22. | Yetkin E, Kilic S, Acikgoz N, Ergin H, Aksoy Y, Sincer I, Aktürk E, Beytur A, Sivri N, Turhan H. Increased prevalence of varicocele in patients with coronary artery ectasia. Coron Artery Dis. 2005;16:261-264. |

| 23. | Androulakis AE, Katsaros AA, Kartalis AN, Stougiannos PN, Andrikopoulos GK, Triantafyllidi EI, Pantazis AA, Stefanadis CI, Kallikazaros IE. Varicose veins are common in patients with coronary artery ectasia. Just a coincidence or a systemic deficit of the vascular wall? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27:519-524. |

| 24. | Koyuncu H, Ergenoglu M, Yencilek F, Gulcan N, Tasdelen N, Yencilek E, Sarica K. The evaluation of saphenofemoral insufficiency in primary adult varicocele. J Androl. 2011;32:151-154. |

| 25. | Canales BK, Zapzalka DM, Ercole CJ, Carey P, Haus E, Aeppli D, Pryor JL. Prevalence and effect of varicoceles in an elderly population. Urology. 2005;66:627-631. |

| 26. | Pavone C, Caldarera E, Liberti P, Miceli V, Di Trapani D, Serretta V, Porcu M, Pavone-Macaluso M. Correlation between chronic prostatitis syndrome and pelvic venous disease: a survey of 2,554 urologic outpatients. Eur Urol. 2000;37:400-403. |

| 27. | Cleave TL. A new conception on the causation, prevention and arrest of varicose veins, varicocele and haemorrhoids. Am J Proctol. 1965;16:35-42. |