Published online Jun 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i21.2626

Revised: January 28, 2011

Accepted: February 4, 2011

Published online: June 7, 2011

AIM: To investigate the diagnostic accuracy of hepatobiliary scintigraphy (HBS) in detecting biliary strictures in living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) patients.

METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed 104 adult LDLT recipients of the right hepatic lobe with duct-to-duct anastomosis, who underwent HBS and cholangiography. The HBS results were categorized as normal, parenchymal dysfunction, biliary obstruction, or bile leakage without re-interpretation. The presence of biliary strictures was determined by percutaneous cholangiography or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

RESULTS: In 89 patients with biliary strictures, HBS showed biliary obstruction in 50 and no obstruction in 39, for a sensitivity of 56.2%. Of 15 patients with no biliary strictures, HBS showed no obstruction in 11, for a specificity of 73.3%. The positive predictive value (PPV) was 92.6% (50/54) and the negative predictive value (NPV) was 22% (11/50). We also analyzed the diagnostic accuracy of the change in bile duct size. The sensitivity, NPV, specificity, and PPV were 65.2%, 27.9%, 80% and 95%, respectively.

CONCLUSION: The absence of biliary obstruction on HBS is not reliable. Thus, when post-LDLT biliary strictures are suspected, early ERCP may be considered.

- Citation: Kim YJ, Lee KT, Jo YC, Lee KH, Lee JK, Joh JW, Kwon CHD. Hepatobiliary scintigraphy for detecting biliary strictures after living donor liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(21): 2626-2631

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i21/2626.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i21.2626

Following the first adult-to-adult right lobe living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) in 1994[1], > 90% of organs for liver transplantation in Asian countries have come from live donations because of the shortage of cadaveric organ donation[2]. Even with the development in various refinements in surgical techniques, multiple biliary reconstructions and smaller bile ducts make right lobe LDLT difficult in comparison with cadaveric whole-size liver transplantation[2]. Although there has been overall improvement in the graft survival rate with advances in the organ preservation method and immunosuppressive management, the postoperative biliary complications have become the focus of concern.

A biliary stricture is one of the most common biliary complications following liver transplantation. The reported incidence of biliary strictures after right lobe LDLT is 28%-43%, which varies according to the type of biliary reconstruction, and with a higher incidence in patients undergoing duct-to-duct anastomosis[3-8]. The short-term consequences of biliary strictures are associated with cholangitis or sepsis, and long-term consequences are related to graft loss, re-transplantation, or even death[9].

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy (HBS) using technetium-99 attached to iminodiacetic acid is a physiological imaging method that is useful for detecting biliary obstruction[10]. There have been some studies to support the diagnostic role of hepatic iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scans in liver-transplanted patients, mainly emphasizing that the abnormal HIDA scan results can predict the biliary complications[11-15]. The subjects in these studies were a relatively heterogeneous group of patients transplanted with different operative techniques (duct-to-duct or end-to-side anastomoses, cadaveric liver transplantation, or LDLT) and different biliary and non-biliary postoperative complications (biliary strictures, bilomas or bile leakage, and vascular compromise). Moreover, these studies were based on retrospective re-interpretations of the HIDA scans, and did not regard the usefulness of the HIDA scan in real clinical decision making. The purpose of the current study was to determine the usefulness of HIDA scans for detecting biliary strictures; specifically in patients with right lobe LDLT by duct-to-duct anastomosis.

This study included 104 LDLT recipients who had HIDA scans and cholangiograms by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous cholangiography (PTC) for suspected biliary strictures between January 2001 and December 2009. The main clinical presentations that led to the evaluation were abnormal blood chemistry at the time of routine visits, or the appearance of symptomatic jaundice or cholangitis. Mebrofenin (bromo-2,4,6-trimethylacetanilidoiminodiacetic acid) was used as a radiopharmaceutical agent for HBS. All 104 LDLTs were performed using the right lobe of the living related donor, and the bile ducts were reconstructed by duct-to-duct anastomosis. The presence of significant biliary strictures on the cholangiogram was regarded as the diagnostic gold standard. We also made a diagnosis of biliary stricture only when a patient had showed improvement after endoscopic or percutaneous intervention, or biliary reconstructive surgery. We reviewed the medical records, and collected the clinical, radiological and laboratory data. In analysis of the ultrasonography (US) or computed tomography (CT) data, intrahepatic duct (IHD) dilatation of new onset or of progression in comparison with previous imaging studies was regarded as a significant change in bile duct size. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Samsung Medical Center and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Based on the nuclear physician’s original interpretation, the results of HIDA scans were classified without retrospective re-interpretation. They were categorized as normal functioning grafts, parenchymal dysfunction, biliary obstruction, or bile leaks. A normal functioning graft was diagnosed when there was an immediate demonstration of hepatic parenchyma, followed sequentially by activity in the intra- and extrahepatic biliary duct system, gallbladder, and upper small bowel within 1 h[16]. Parenchymal dysfunction was considered to be present when abnormal hepatic uptake and/or abnormal excretion was noted. Scintigraphic diagnosis of biliary obstruction was made when bowel activity was not detected within 4 h, regardless of hepatic uptake. Bile leakage was diagnosed when accumulation of tracer was noted at an abnormal physiological site[12].

To describe the baseline patient characteristics, the mean ± SD was used for continuous variables with a normal distribution, and the median value was used for continuous variables without a normal distribution. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were used to investigate the accuracy as a diagnostic tool.

Detailed baseline clinical characteristics of the study subjects are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 51.5 years, and there was a male predominance. Hepatic failure and hepatic malignancy constituted one-half of the indications for liver transplantation. Hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma and HBV-related hepatic failure accounted for 39.4% and 31.7% of the cases, respectively. Other causes of hepatic failure not shown in Table 1 included drug-induced liver injury, chronic alcoholism, autoimmune hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis. Other hepatic malignancies that led to LDLT were hepatocellular carcinoma associated with chronic alcoholism and hepatic angiosarcoma. The interval between LDLT and HIDA scan ranged between 25 and 1490 d (median: 294.5 d). Table 2 describes the baseline laboratory characteristics of the patients. All 104 patients had imaging studies (US or CT) for evaluation of biliary strictures, and 61 patients (58.7%) had significant changes in bile duct size. Cholangiograms were taken by ERCP in 56 patients (53.8%) and by PTC in 48 patients (46.2%), and a total of 89 patients (85.6%) had significant biliary strictures. Management of biliary stricture was successful using an endoscopic or percutaneous approach in 80 patients. However, interventions failed in nine patients and they required Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, eventually. The median value of the interval between the day of LDLT and the diagnosis of biliary stricture in 89 patients was 309 d (range: 37-1490 d).

| Variable | Result |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 51.5 ± 8.25 |

| Male/female, n (%) | 82/22 (79/21) |

| Indication for liver transplantation, n (%) | |

| Hepatic failure | 52 (50) |

| HBV infection | 33 (31.7) |

| HCV infection | 5 (4.8) |

| Others | 14 (13.5) |

| Malignancy | 52 (50) |

| HCC, HBV-related | 41 (39.4) |

| HCC, HCV-related | 7 (6.7) |

| Others | 4 (3.9) |

| Interval between LDLT and HIDA scan, d, median (range) | 294.5 (25-1490) |

| Laboratory test | Result |

| Bilirubin, mg/dL, median (range) | 3.7 (0.6-44) |

| AST, U/L, median (range) | 85 (15-336) |

| ALT, U/L, median (range) | 132 (6-798) |

| ALP, U/L, median (range) | 271 (65-988) |

| GGT, U/L, median (range) | 297 (28-1491) |

| Change of bile duct size, n (%) | |

| Present | 61 (58.7) |

| None | 43 (41.3) |

| Stricture on the cholangiogram, n (%) | |

| Present | 89 (85.6) |

| None | 15 (14.4) |

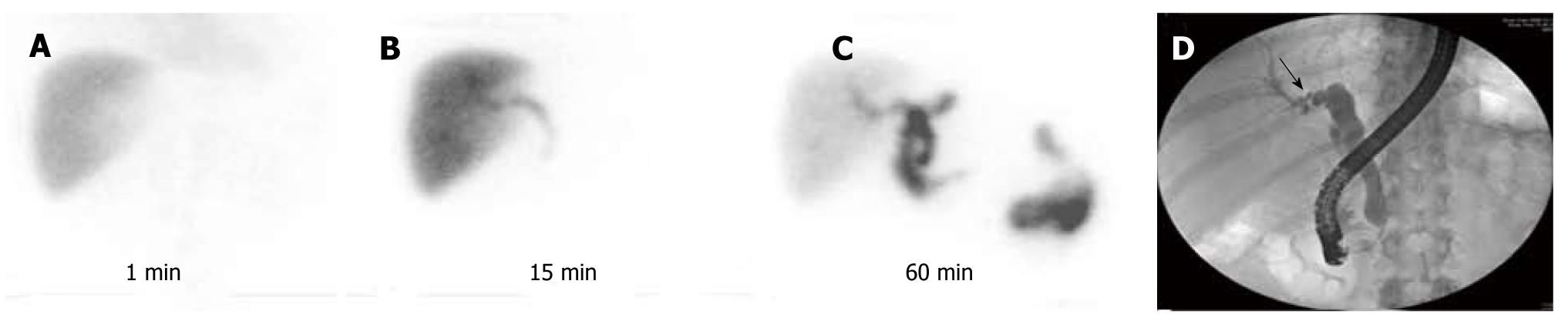

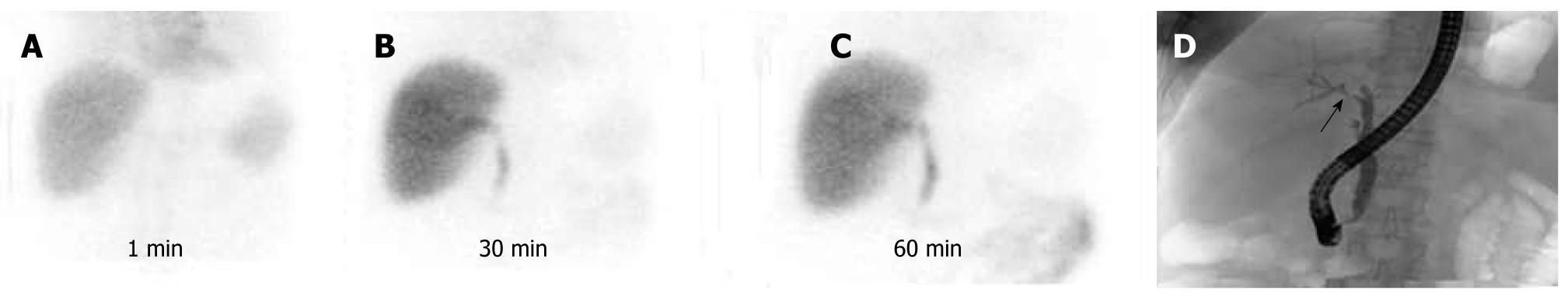

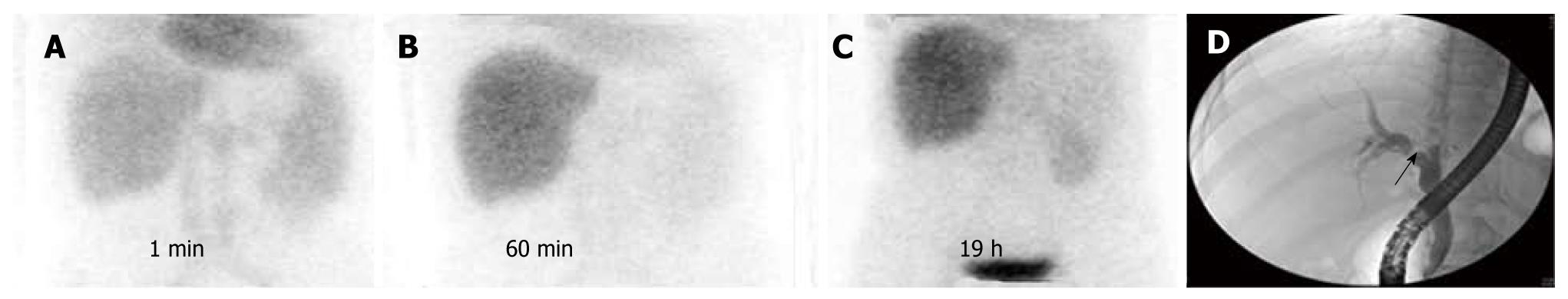

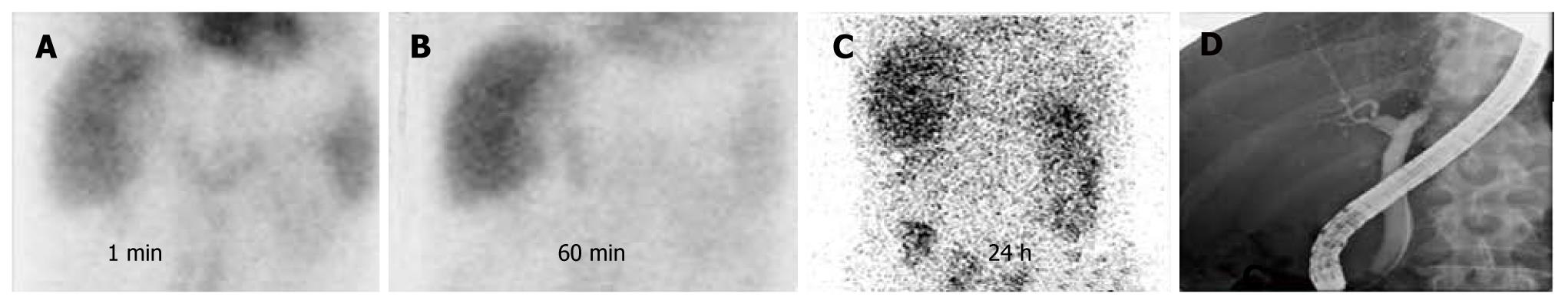

The results of HIDA scans and the presence of significant biliary strictures on the cholangiograms were matched, as in Table 3. Of 89 patients with biliary strictures, HIDA scans suggested a normal functioning liver graft (Figure 1) in six patients (6.7%), parenchymal dysfunction (Figure 2) in 32 (35.9%), biliary obstruction (Figure 3) in 50 (56.2%), and the presence of bile leakage in one (1.2%). The HIDA scans suggested the presence of biliary obstruction in four of 15 patients with no significant biliary strictures on cholangiograms as presented in Figure 4. All four patients with false-positive results on HIDA scans were confirmed to have allograft rejection after liver biopsy. Three of them received intravenous steroid pulse therapy and maintained graft function. However, one patient developed hepatic failure in spite of medical therapy, and he underwent re-transplantation.

| Normal | Parenchymal dysfunction | Biliary obstruction | Bileleakage | Total | |

| 8 (7.7) | 41 (39.4) | 54 (51.9) | 1 (1) | 104 (100) | |

| Stricture on cholangiogram | 6 | 32 | 50 | 1 | 89 |

| No stricture on cholangiogram | 2 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 15 |

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of HIDA scans to detect post-LDLT biliary strictures were 56.2% (50/89), 73.3% (11/15), 92.6% (50/54), and 22% (11/50), respectively. All 104 patients had imaging studies with US or CT in the evaluation process. When using the change in bile duct size on US or CT as a diagnostic tool (Table 4), the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 65.2% (58/89), 80% (12/15), 95% (58/61), and 27.9% (12/43).

| Stricture on cholangiogram (+) | Stricture on cholangiogram (-) | Total | |

| Change in bile duct size (+) | 58 | 3 | 61 |

| Change in bile duct size (-) | 31 | 12 | 43 |

| Total | 89 | 15 | 104 |

Although there are various etiologies for liver function test abnormalities in liver transplant patients, rejection and biliary strictures are the most common and important causes of morbidity and mortality. These two conditions require different treatment strategies, so accurate differentiation is essential for proper management.

HBS using a radionuclide agent is a diagnostic imaging study that evaluates hepatocellular function and patency of the biliary system by tracing the production and flow of bile from the liver through the biliary system into the small intestine[16]. As a result of its non-invasiveness and convenience, HBS is commonly used to evaluate the presence of biliary strictures[3]. Even though older studies have concluded that HBS can differentiate intrahepatic cholestasis from pure hepatocyte damage in liver transplant patients[17,18], HBS cannot distinguish between cholestasis and rejection[18]. In the current study, the specificity, PPV, sensitivity, and NPV of HIDA scans in detecting post-LDLT biliary strictures were 73.3%, 92.6%, 56.2%, and 22%, respectively. Thus, HIDA scans cannot predict the presence of biliary obstruction in about 50% of the patients with significant biliary strictures. Surprisingly, six of eight patients with normal HIDA scan results were shown to have biliary strictures on cholangiograms. The normal HIDA scan results in patients with biliary strictures might be a reflection of post-LDLT biliary strictures that represent low-grade partial biliary obstruction. In the case of high-grade obstruction, there is usually prompt hepatic uptake, but no secretion of the radiotracer into biliary ducts after 4 h[12,13], and sometimes even after 24 h[10,16]. However, the typical scintigraphic imaging findings with low-grade or partial biliary obstruction include good hepatic uptake, normal secretion into the biliary ducts, and slightly delayed secretion into the bowel[10,16]. Another remarkable finding in the current study was that 32 of 41 patients who had parenchymal dysfunction on HIDA scans had biliary strictures on the cholangiograms. With prolonged biliary obstruction, concomitant hepatic dysfunction may occur, so decreased hepatic uptake of radionuclide trace can be seen prominently[16]. As shown in Table 3, four patients with no biliary strictures on cholangiograms had allograft rejection. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies, and some patients with rejection and severely elevated serum bilirubin levels have scintigraphic findings of total biliary obstruction[12,17]. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that the histological finding of rejection is characterized by the diagnostic triad of portal inflammatory mixed infiltrates, venous endotheliitis, and bile duct injury, and lack of hepatolysis as a dominant feature[19,20]. This result again confirms that HIDA scans do not have a role in the differential diagnosis of rejection and biliary strictures; the most important clinical situations.

Considering the relatively good PPV, the presence of biliary obstruction on HIDA scans can be quite reliable, and might offer a good rationale for clinicians proceeding to the next step (ERCP or PTC to confirm the presence of biliary strictures) and to initiate definitive treatment. The real problem in clinical practice occurs when the HIDA scan shows negative results, parenchymal dysfunction, or a normal functioning graft. This false negativity may guide the clinician to proceed to another diagnostic modality, most commonly a liver biopsy, and can create a delay in the proper diagnosis and management.

Cholangiography, either by ERCP or PTC, is considered to be the gold standard for post-liver transplantation biliary strictures, not only in establishing the diagnosis, but also in allowing therapeutic intervention in the same setting. ERCP has an advantage over PTC in that it is not only more physiological, but also less invasive. Moreover, recent studies have demonstrated an approximately 70% overall success rate for endoscopic treatment of post-LDLT biliary strictures with duct-to-duct anastomosis[5-9,21,22]. Biliary drainage with the percutaneous approach can be considered as a second option for cases not suitable for endoscopic management[22].

The suspicion for post-LDLT biliary strictures often begins with abnormal liver function tests or clinical evidence of obstructive cholangitis[9,23]. When a biliary stricture is suspected, imaging studies are commonly performed first because of non-invasiveness and convenience. The first step in establishing the diagnosis is usually US of the abdomen[9], which has the advantage that additional information about hepatic vascular patency is provided. However, US evaluation of the biliary tree is known to be of limited value because bile duct dilatation in liver transplant patients can be a non-specific postoperative finding, and the absence of dilatation has been noted to be an unreliable indicator of biliary obstruction[24]. The low sensitivity of US in evaluation of the biliary tree of 38%-66% has been the major drawback to US serving as a meaningful modality in the decision-making process[3]. However, these studies primarily reflect the outcomes during the period of cadaveric liver transplantation. There have been no recent data about the usefulness of change in bile duct size on US or CT in detecting post-transplantation biliary strictures in patients with LDLT. In the present study, to identify specifically clinically relevant changes in bile duct size, we only considered IHD dilatation of new onset or of marked progression. The sensitivity of this criterion was 65.2% and the NPV was 27.9%, which is still lower than that for a good diagnostic modality, but a higher rate than for HIDA scans. The specificity and the PPV were 80% and 95%, respectively, and again suggested that a significant change in bile duct caliber is mandatory to proceed in ERCP or PTC.

Recently, some studies have indicated that magnetic resonance cholangiography is a non-invasive and promising diagnostic modality with a sensitivity and specificity rate > 90%[25-27]. However, it has a limitation in that the therapeutic intervention is impossible, so cost-effectiveness is of concern. Also, it needs further validation in LDLT recipients by duct-to-duct anastomosis.

In conclusion, HIDA scans had relatively reliable specificity and PPV for detecting post-LDLT biliary strictures, but the sensitivity and NPV were poor. The absence of significant biliary obstruction on HBS cannot be a reliable marker for clinicians. Therefore, early performance of ERCP or PTC may be necessary to diagnose and treat biliary strictures, even though the HIDA scan results are negative, considering the successful outcome of ERCP or PTC in the treatment of biliary strictures.

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) has become the mainstream for liver transplantation to overcome the shortage of cadaveric donors. However, the higher risks or biliary complications remain the primary concern. Stricture is one of the most common biliary complications after LDLT.

Hepatobiliary scan (HBS) is a diagnostic modality that is useful for detecting biliary obstruction and evaluating hepatocellular function. Several studies have evaluated the role of HBS for detecting biliary stricture in transplanted liver. However, the information is limited and insufficient because most of the studies were performed in the period of cadaveric LT.

To evaluate the role of HBS in real clinical settings, the authors included 104 patients who underwent LDLT and HBS. The HBS results were used without re-interpretation. Although HBS showed relatively reliable specificity and positive predictive value for detecting post-LDLT biliary strictures, the sensitivity and negative predictive value were poor. In particular, it did not distinguish between biliary stricture and rejection.

Even though the HBS results do not suggest the possibility of biliary obstruction, early performance of cholangiography may be necessary to diagnose and treat biliary strictures.

The paper shows that scintigraphy is not a good indicator of modality in post-transplant biliary strictures.

Peer reviewer: Yogesh K Chawla, Dr., Professor, Department of Hepatology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh 160012, India

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Yamaoka Y, Washida M, Honda K, Tanaka K, Mori K, Shimahara Y, Okamoto S, Ueda M, Hayashi M, Tanaka A. Liver transplantation using a right lobe graft from a living related donor. Transplantation. 1994;57:1127-1130. |

| 2. | Lee SG. Living-donor liver transplantation in adults. Br Med Bull. 2010;94:33-48. |

| 3. | Sharma S, Gurakar A, Jabbour N. Biliary strictures following liver transplantation: past, present and preventive strategies. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:759-769. |

| 4. | Yazumi S, Chiba T. Biliary complications after a right-lobe living donor liver transplantation. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:861-865. |

| 5. | Hisatsune H, Yazumi S, Egawa H, Asada M, Hasegawa K, Kodama Y, Okazaki K, Itoh K, Takakuwa H, Tanaka K. Endoscopic management of biliary strictures after duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction in right-lobe living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;76:810-815. |

| 6. | Seo JK, Ryu JK, Lee SH, Park JK, Yang KY, Kim YT, Yoon YB, Lee HW, Yi NJ, Suh KS. Endoscopic treatment for biliary stricture after adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:369-380. |

| 7. | Kato H, Kawamoto H, Tsutsumi K, Harada R, Fujii M, Hirao K, Kurihara N, Mizuno O, Ishida E, Ogawa T. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic management for biliary strictures after living donor liver transplantation with duct-to-duct reconstruction. Transpl Int. 2009;22:914-921. |

| 8. | Chang JH, Lee IS, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Kim DG, You YK, Chun HJ, Lee DK, Choi MG, Chung IS. Biliary Stricture after Adult Right-Lobe Living-Donor Liver Transplantation with Duct-to-Duct Anastomosis: Long-Term Outcome and Its Related Factors after Endoscopic Treatment. Gut Liver. 2010;4:226-233. |

| 9. | Verdonk RC, Buis CI, Porte RJ, Haagsma EB. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: a review. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2006;89-101. |

| 10. | Ziessman HA. Nuclear medicine hepatobiliary imaging. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:111-116. |

| 11. | Kurzawinski TR, Selves L, Farouk M, Dooley J, Hilson A, Buscombe JR, Burroughs A, Rolles K, Davidson BR. Prospective study of hepatobiliary scintigraphy and endoscopic cholangiography for the detection of early biliary complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Br J Surg. 1997;84:620-623. |

| 12. | Kim JS, Moon DH, Lee SG, Lee YJ, Park KM, Hwang S, Lee HK. The usefulness of hepatobiliary scintigraphy in the diagnosis of complications after adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:473-479. |

| 13. | Gencoglu EA, Kocabas B, Moray G, Aktas A, Karakayali H, Haberal M. Usefulness of hepatobiliary scintigraphy for the evaluation of living related liver transplant recipients in the early postoperative period. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:234-237. |

| 14. | Al Sofayan MS, Ibrahim A, Helmy A, Al Saghier MI, Al Sebayel MI, Abozied MM. Nuclear imaging of the liver: is there a diagnostic role of HIDA in posttransplantation? Transplant Proc. 2009;41:201-207. |

| 15. | Concannon RC, Howman-Giles R, Shun A, Stormon MO. Hepatobiliary scintigraphy for the assessment of biliary strictures after pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13:977-983. |

| 16. | Balon HR, Fink-Bennett DM, Brill DR, Fig LM, Freitas JE, Krishnamurthy GT, Klingensmith WC, Royal HD. Procedure guideline for hepatobiliary scintigraphy. Society of Nuclear Medicine. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1654-1657. |

| 17. | Kuni CC, Engeler CM, Nakhleh RE, duCret RP, Boudreau RJ. Correlation of technetium-99m-DISIDA hepatobiliary studies with biopsies in liver transplant patients. J Nucl Med. 1991;32:1545-1547. |

| 18. | Engeler CM, Kuni CC, Nakhleh R, Engeler CE, duCret RP, Boudreau RJ. Liver transplant rejection and cholestasis: comparison of technetium 99m-diisopropyl iminodiacetic acid hepatobiliary imaging with liver biopsy. Eur J Nucl Med. 1992;19:865-870. |

| 19. | Snover DC, Freese DK, Sharp HL, Bloomer JR, Najarian JS, Ascher NL. Liver allograft rejection. An analysis of the use of biopsy in determining outcome of rejection. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:1-10. |

| 20. | Freese DK, Snover DC, Sharp HL, Gross CR, Savick SK, Payne WD. Chronic rejection after liver transplantation: a study of clinical, histopathological and immunological features. Hepatology. 1991;13:882-891. |

| 21. | Soejima Y, Taketomi A, Yoshizumi T, Uchiyama H, Harada N, Ijichi H, Yonemura Y, Ikeda T, Shimada M, Maehara Y. Biliary strictures in living donor liver transplantation: incidence, management, and technical evolution. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:979-986. |

| 22. | Kim ES, Lee BJ, Won JY, Choi JY, Lee DK. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage may serve as a successful rescue procedure in failed cases of endoscopic therapy for a post-living donor liver transplantation biliary stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:38-46. |

| 23. | Wojcicki M, Milkiewicz P, Silva M. Biliary tract complications after liver transplantation: a review. Dig Surg. 2008;25:245-257. |

| 24. | Zemel G, Zajko AB, Skolnick ML, Bron KM, Campbell WL. The role of sonography and transhepatic cholangiography in the diagnosis of biliary complications after liver transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151:943-946. |

| 25. | Linhares MM, Gonzalez AM, Goldman SM, Coelho RD, Sato NY, Moura RM, Silva MH, Lanzoni VP, Salzedas A, Serra CB. Magnetic resonance cholangiography in the diagnosis of biliary complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:947-948. |

| 26. | Boraschi P, Braccini G, Gigoni R, Sartoni G, Neri E, Filipponi F, Mosca F, Bartolozzi C. Detection of biliary complications after orthotopic liver transplantation with MR cholangiography. Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;19:1097-1105. |