Published online Jan 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i2.236

Revised: October 15, 2010

Accepted: October 22, 2010

Published online: January 14, 2011

AIM: To investigate the current seroprevalence of hepatitis A virus (HAV) antibodies in patients with chronic viral liver disease in Korea. We also tried to identify the factors affecting the prevalence of HAV antibodies.

METHODS: We performed an analysis of the clinical records of 986 patients (mean age: 49 ± 9 years, 714 males/272 females) with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection who had undergone HAV antibody testing between January 2008 and December 2009.

RESULTS: The overall prevalence of IgG anti-HAV was 86.61% (854/986) in patients with chronic liver disease and was 88.13% (869/986) in age- and gender-matched patients from the Center for Health Promotion. The anti-HAV prevalence was 80.04% (405/506) in patients with chronic hepatitis B, 86.96% (20/23) in patients with chronic hepatitis C, 93.78% (422/450) in patients with HBV related liver cirrhosis, and 100% (7/7) in patients with HCV related liver cirrhosis. The anti-HAV prevalence according to the decade of age was as follows: 20s (6.67%), 30s (50.86%), 40s (92.29%), 50s (97.77%), and 60s (100%). The anti-HAV prevalence was significantly higher in patients older than 40 years compared with that in patients younger than 40 years of age. Multivariable analysis showed that age ≥ 40 years, female gender and metropolitan cities as the place of residence were independent risk factors for IgG anti-HAV seropositivity.

CONCLUSION: Most Korean patients with chronic liver disease and who are above 40 years of age have already been exposed to hepatitis A virus.

- Citation: Cho HC, Paik SW, Kim YJ, Choi MS, Lee JH, Koh KC, Yoo BC, Son HJ, Kim SW. Seroprevalence of anti-HAV among patients with chronic viral liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(2): 236-241

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i2/236.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i2.236

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is an epidemiologically important virus with a worldwide distribution and causes acute hepatitis in humans. This virus has been responsible for numerous disease outbreaks resulting from close personal contact or sexual contact[1-3], contaminated food or water[3-7], injection drug use[8,9] and other modes of transmission[8,10].

The pattern of this disease includes infection during early childhood followed by life-long immunity[11]. When acquired in childhood, HAV is a very benign disease, over 70% of patients are asymptomatic and fulminant liver failure is extremely rare[12,13]. When the infection occurs in adulthood, a much more prolonged course is seen and the rate of jaundice and fulminant liver failure is much higher[12-14].

During recent decades, due to improvements in sanitation and hygiene, the age of infection by this virus has shifted from early childhood to adolescence or even later[11,15,16]. Although the overall case-fatality rate of acute HAV among persons of all ages is only 0.01%-0.3%[17-19], it is higher (1.8%) among adults who are 50 years of age or older[19]. More importantly, acute HAV superinfection causes severe liver disease, acute liver failure and even higher mortality rates in patients with underlying chronic liver disease (CLD). Numerous studies have identified CLD as a risk factor for fulminant hepatitis and death from acute HAV infection[7,20-29].

The aim of this study was to investigate the current seroprevalence of HAV antibodies (anti-HAV) in patients with chronic viral liver disease in South Korea. We also tried to determine the age-specific seroprevalence in these patients to assess whether vaccination against HAV is necessary in all patients who have underlying viral liver diseases, and to determine the factors that affect IgG anti-HAV seropositivity.

We identified a total of 986 patients with chronic viral liver disease who had undergone HAV antibody testing between June 2008 and December 2009 at the Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea. The inclusion criteria consisted of hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity or hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies (anti-HCV) and HCV RNA positivity in more than two tests for at least 6 mo. Patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and a past medical history of HAV vaccination were excluded from this study.

The status of underlying liver disease was classified into chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis (LC). The diagnosis of LC was made if any one of the following findings was met: (1) compatible intraoperative gross findings or histologically compatible findings; (2) evidence of portal hypertension in patients with liver disease; and (3) compatible radiologic findings and platelet counts less than 100 × 109/L.

During the same period, 986 age- and gender-matched patients from the Center for Health Promotion were selected as the control group by one-to-one matching, and the study was statistically powered at 89%. There was no loss of subjects in the case group. Patients from the Center for Health Promotion who tested positive for HBsAg or anti-HCV and had a medical history of liver disease were excluded.

Commercially available immunoassays (Anti-HAV IgG IRMA kit, North Institute of Biological Technology, Beijing, China; ARCHITECT HBsAg assay, Abbott Laboratories, Sligo, Ireland; ADVIA Centaur HCV assay, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA, USA) were used to detect IgG anti-HAV, HBsAg and anti-HCV, respectively. The HCV RNA was amplified by RNA PCR and hybridization methods (COBAS® Amplicor HCV test version 2.0, Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA, lower limit of detection 50 IU/mL).

The Cochran-Armitage trend test was used to assess the association between age and seropositivity rate for anti-HAV. McNemar’s test was used to compare the seropositivity rate for anti-HAV between patients with CLD and patients from the Center for Health Promotion. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine the relationship between the variables and seropositivity for anti-HAV.

P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant and Bonferroni’s method was used to correct for inflated type I error due to multiple testing. All the statistical analyses were run on SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The institutional review board of Samsung Medical Center approved this retrospective study.

The patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 49 years (range: 20-80 years) and the vast majority of patients were over 40 years old (84%). A male preponderance (72.41%) was observed and the vast majority of patients had chronic viral hepatitis B (51.32%) and HBV related LC (45.64%). A relatively large proportion of the patients were from Seoul, the capital of South Korea (39.45%). The overall prevalence of IgG anti-HAV in patients with CLD was 86.61% (854/986).

| Variable | n (%) |

| Mean age (yr, range) | 49 ± 9 (20-80) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 272 (27.59) |

| Male | 714 (72.41) |

| Chronic liver disease | |

| Chronic viral hepatitis B | 506 (51.32) |

| Chronic viral hepatitis C | 23 (2.33) |

| HBV related liver cirrhosis | 450 (45.64) |

| HCV related liver cirrhosis | 7 (0.71) |

| Place of residence | |

| Seoul | 389 (39.45) |

| Gyeonggi-do | 274 (27.79) |

| Metropolitan cities | 101 (10.24) |

| Other provinces | 223 (22.62) |

| Prevalence of IgG anti-HAV | 854 (86.61) |

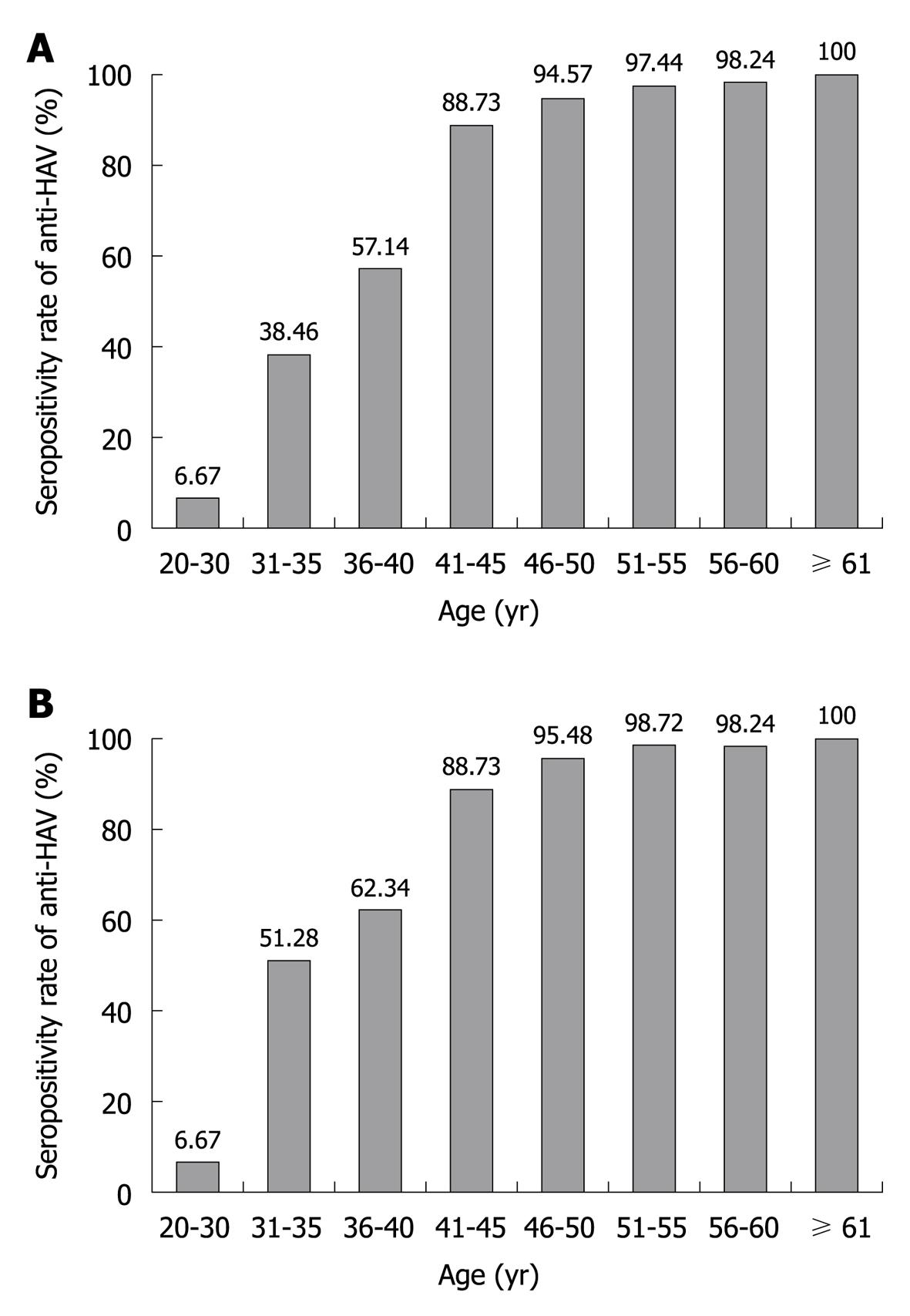

When the study participants were classified by decade of age into five groups, from 20s to more than 60 years old, the anti-HAV seroprevalence was 6.67% and 50.86% in the patients in their 20s and 30s, respectively. The positivity rate for anti-HAV in the patients in their 40s, 50s and 60s was 92.29%, 97.77% and 100%, respectively. The prevalence of IgG anti-HAV in patients with CLD, and as divided by 5-year age intervals, is shown in Figure 1A. The seropositivity rate for anti-HAV increased gradually as age increased (P < 0.001). The anti-HAV prevalence was significantly higher in patients older than 40 years compared with those patients younger than 40 years of age (94.95% vs 33.58%, respectively, P < 0.001).

The prevalence of IgG anti-HAV according to age in the age- and gender-matched patients from the Center for Health Promotion is shown in Figure 1B. The overall prevalence of anti-HAV was 88.13% (869/986) and the seropositivity rate for anti-HAV increased gradually as age increased (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the anti-HAV seroprevalence between patients with CLD and those from the Center for Health Promotion (P = 0.141).

The overall prevalence of anti-HAV was 86.51% in the 956 patients with chronic HBV infection, and it was 90% in the 30 patients with chronic HCV infection. There was no statistically significant difference in seropositivity for anti-HAV between the patients with HBV infection and those with HCV infection (P = 0.582). For the HBsAg-positive patients, the anti-HAV prevalence in each group divided by the decade of age increased gradually as age increased, which was similar for all the patients (Table 2).

| Age (yr) | Anti-HAV/HBV | Anti-HAV/HCV |

| 20-30 | 3/43 (6.98) | 0 |

| 31-40 | 58/112 (51.79) | 0/2 (0) |

| 41-50 | 325/351 (92.59) | 6/7 (85.71) |

| 51-60 | 378/387 (97.67) | 12/12 (100) |

| ≥ 61 | 63/63 (100) | 9/9 (100) |

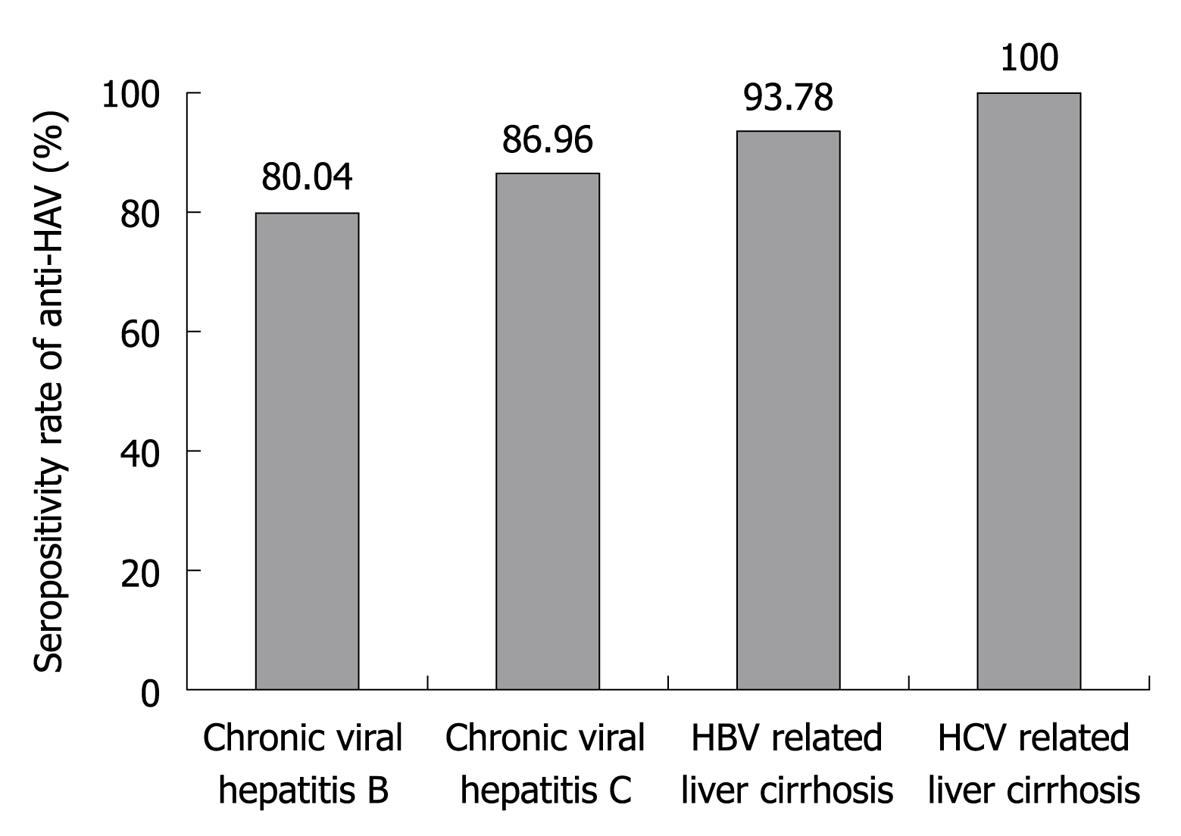

The prevalence of IgG anti-HAV according to the status of CLD is shown in Figure 2. The anti-HAV seroprevalence was 80.04% (405/506) in patients with chronic hepatitis B, 86.96% (20/23) in patients with chronic hepatitis C, 93.78% (422/450) in patients with HBV related LC and 100% (7/7) in patients with HCV related LC.

The anti-HAV prevalence according to gender, the status of liver disease and place of residence is shown in Table 3. Anti-HAV was more frequently detected in female patients (90.07%) than in male patients (85.29%, P = 0.049). As for the status of liver disease, anti-HAV antibody was more frequently detected in patients with LC (93.87%) than in those with chronic hepatitis (80.34%, P < 0.001). As for the place of residence, anti-HAV antibody was less frequently detected among patients who lived in Seoul or Gyeonggi-do (79.95%-87.96%) than among those living in metropolitan cities or other provinces (92.38%-95.05%, P < 0.001).

| Characteristics | Anti-HAV positivity, n (%) | P value |

| Sex | 0.049 | |

| Male | 609/714 (85.29) | |

| Female | 245/272 (90.07) | |

| Status of liver disease | < 0.001 | |

| Chronic viral hepatitis | 425/529 (80.34) | |

| Liver cirrhosis | 429/457 (93.87) | |

| Place of residence | < 0.001 | |

| Seoul | 311/389 (79.95) | |

| Gyeonggi-do | 241/274 (87.96) | |

| Metropolitan cities | 96/101 (95.05) | |

| Other provinces | 206/223 (92.38) |

Multivariable analysis of the factors for anti-HAV seropositivity is shown in Table 4. Age ≥ 40 years (P < 0.001), female gender (P = 0.014) and metropolitan cities as the place of residence (P = 0.012) were independent risk factors for IgG anti-HAV seropositivity.

| Characteristics | Anti-HAV positivity, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Age (≥ 40 yr) | 809/852 (94.95) | 33.44 (20.14-55.52) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 245/272 (90.07) | 2.07 (1.16-3.71) | 0.014 |

| Etiology | 0.487 | ||

| HBV | 827/956 (86.51) | 1 | |

| HCV | 27/30 (90) | 0.61 (0.15-2.47) | |

| Status of liver disease | 0.075 | ||

| Chronic viral hepatitis | 425/529 (80.34) | 1 | |

| Liver cirrhosis | 429/457 (93.87) | 1.64 (0.95-2.82) | |

| Place of residence | 0.035 | ||

| Seoul | 311/389 (79.95) | 1 | |

| Gyeonggi-do | 241/274 (87.96) | 1.51 (0.86-2.66) | 0.153 |

| Metropolitan cities | 96/101 (95.05) | 4.11 (1.37-12.35) | 0.012 |

| Other provinces | 206/223 (92.38) | 1.84 (0.93-3.65) | 0.080 |

The epidemiological pattern of HAV infection is currently changing in many developing countries. An improved socioeconomic status, more sanitary conditions and better hygiene practices have reduced the incidence of HAV infection, and the age-specific HAV seroprevalence in the general population has steadily decreased. The decrease in HAV infection in young adults has resulted in a reduction in individuals with protective antibody and increased hepatitis A in the adult population. In Korea, symptomatic hepatitis A has been gradually increasing since the mid-1990s, with a tendency toward an increase in the mean age and disease severity[30-35].

A number of studies have suggested that the clinical course of HAV infection is more severe in patients with CLD[7,20-29]. Mortality in patients with HBsAg was found to be significantly higher than that in patients without HBsAg in an outbreak of HAV infection in Shanghai[23], and an analysis of HAV associated deaths in the United States revealed a higher rate of fatality in HBV carriers than in patients without HBV[24]. Moreover, patients with HCV infection were reported to experience HAV associated fulminant hepatic failure more often than those patients without CLD. In a prospective cohort study of adults with HCV infection, Vento et al[31] reported that 41.2% of patients with acute HAV superinfection developed acute liver failure and 35.3% died.

In our study, the overall seroprevalence of IgG anti-HAV in the 986 Korean patients with chronic viral liver disease was 86.61%. When the study participants were classified by the decade of age, the anti-HAV seroprevalence was 6.67%, 50.86%, 92.29%, 97.77% and 100% in patients in their 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s, respectively. These results are consistent with recent Korean studies[28,29]. The anti-HAV prevalence was significantly higher in patients older than 40 years compared with those younger than 40 years of age (94.95% vs 33.58%, respectively). These data indicate that most patients with chronic viral liver diseases and who are above 40 years of age have already been exposed to HAV infection, and have naturally acquired immunity against HAV. Hence, vaccination against HAV should be considered in young anti-HAV-negative patients.

In the present study, we expected the seroprevalence of anti-HAV to be higher in patients with CLD than in those from the Center for Health Promotion, considering the relatively low socioeconomic status of the CLD patients. However, there was no statistically significant difference in anti-HAV seroprevalence between the two groups (86.61% vs 88.13%, respectively, P = 0.141). This finding may indicate that the immune response to HAV infection is not altered by chronic infection with either HBV or HCV. This result is also consistent with the results of the multivariable analysis in our study.

As shown in the multivariable analysis and Figure 1A, patient age was the most important factor for determining the seropositivity rate of IgG anti-HAV. Although anti-HAV was more frequently detected in patients with LC than in those with chronic viral hepatitis (93.87% vs 80.34%, respectively), this was probably attributable to age when considering the results of the multivariable analysis. Female patients had a relatively higher rate of HAV seropositivity. This finding might be explained by the fact that female subjects in Korea have a larger number of social and household contacts and so probably have more exposure to HAV. We also observed significant differences among the places of residence. The lowest seroprevalence was observed in Seoul, the largest and most urbanized city in Korea, and the highest was in the provinces, with a more rural way of life. Such differences in seroprevalence might well be attributed to the vast variations in living conditions.

The current study has a couple of limitations. First, this is a retrospective study and the available epidemiological data on HAV infection is limited. Socioeconomic characteristics, including the educational level, salary, the number of siblings, the type of residence, the water supply, etc., were not included in this study. Although multivariable analysis of the seropositivity of anti-HAV was carried out with relatively limited variables, the results in the present study may not be applicable to all patients with CLD. Second, although the current study included a large number of CLD patients, it was performed at a single medical center. Therefore, the patients may not be representative of the whole population of Korea. We also used data from the Center for Health Promotion and these patients may not be representative of the general Korean population without CLD when considering the fact that patients with a relatively higher level of socioecomonic status visit the Center for Health Promotion.

In conclusion, the overall prevalence of IgG anti-HAV in Korean patients with chronic viral liver disease was 86.61%, and most patients who are above 40 years of age have already been exposed to HAV. Therefore, vaccination against HAV should be considered, particularly for young anti-HAV-negative patients with chronic liver disease.

An improved socioeconomic status, more sanitary conditions and better hygiene practices have reduced the incidence of hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection. In Korea, symptomatic hepatitis A has been gradually increasing since the mid-1990s, with a tendency toward an increase in the mean age and disease severity. Acute HAV superinfection causes severe liver disease, acute liver failure and even higher mortality rates in patients with underlying chronic liver disease.

Identifying the current seroprevalence of HAV antibodies in patients with chronic viral liver disease would be valuable for establishing appropriate vaccination guidelines for patients with chronic liver disease.

Recent studies reported a rapid epidemiological shift in HAV infection. In this study, the authors evaluated seroprevalence of IgG anti-HAV in patients with chronic liver disease using large population based data, and investigated the age-specific seroprevalence and the factors that affect IgG anti-HAV seropositivity.

There has been an apparent epidemiological shift in HAV seroprevalence in patients with chronic liver disease. Most patients who are above 40 years of age have already been exposed to HAV. Therefore, vaccination against HAV should be considered, particularly for young anti-HAV-negative patients with chronic liver disease.

This manuscript is of interest.

Peer reviewers: Fernando Fornari, MD, Department of Gastroenterology, Universidade de Passo, Fundo, Rua Teixeira Soares, 817, 99010080 Passo Fundo, Brazil; Fen Liu, MD, University of Minnesota, 6155 Jackson Hall, 321 Church Street Se, Minneapolis, MN 55455, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Cotter SM, Sansom S, Long T, Koch E, Kellerman S, Smith F, Averhoff F, Bell BP. Outbreak of hepatitis A among men who have sex with men: implications for hepatitis A vaccination strategies. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1235-1240. |

| 2. | Cooksley WG. What did we learn from the Shanghai hepatitis A epidemic? J Viral Hepat. 2000;7 Suppl 1:1-3. |

| 3. | Bell BP, Shapiro CN, Alter MJ, Moyer LA, Judson FN, Mottram K, Fleenor M, Ryder PL, Margolis HS. The diverse patterns of hepatitis A epidemiology in the United States-implications for vaccination strategies. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1579-1584. |

| 4. | Public health dispatch: multistate outbreak of hepatitis A among young adult concert attendees--United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:844-845. |

| 5. | Franco E, Giambi C, Ialacci R, Coppola RC, Zanetti AR. Risk groups for hepatitis A virus infection. Vaccine. 2003;21:2224-2233. |

| 6. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis Surveillance Report No. 58. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2003; . |

| 7. | Moon HW, Cho JH, Hur M, Yun YM, Choe WH, Kwon SY, Lee CH. Laboratory characteristics of recent hepatitis A in Korea: ongoing epidemiological shift. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1115-1118. |

| 9. | Almasio PL, Amoroso P. HAV infection in chronic liver disease: a rationale for vaccination. Vaccine. 2003;21:2238-2241. |

| 10. | Wang JY, Lee SD, Tsai YT, Lo KJ, Chiang BN. Fulminant hepatitis A in chronic HBV carrier. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:109-111. |

| 11. | Lednar WM, Lemon SM, Kirkpatrick JW, Redfield RR, Fields ML, Kelley PW. Frequency of illness associated with epidemic hepatitis A virus infections in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:226-233. |

| 12. | Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 1999;48:1-37. |

| 13. | Yao G. Clinical spectrum and natural history of viral hepatitis A in a 1988 Shanghai epidemic. Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins 1991; 76-78. |

| 14. | Keeffe EB. Is hepatitis A more severe in patients with chronic hepatitis B and other chronic liver diseases? Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:201-205. |

| 15. | Koff RS. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of hepatitis A virus infection. Vaccine. 1992;10 Suppl 1:S15-S17. |

| 16. | Lefilliatre P, Villeneuve JP. Fulminant hepatitis A in patients with chronic liver disease. Can J Public Health. 2000;91:168-170. |

| 17. | Fiore AE. Hepatitis A transmitted by food. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:705-715. |

| 18. | Hutin YJ, Pool V, Cramer EH, Nainan OV, Weth J, Williams IT, Goldstein ST, Gensheimer KF, Bell BP, Shapiro CN. A multistate, foodborne outbreak of hepatitis A. National Hepatitis A Investigation Team. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:595-602. |

| 19. | Song MH, Lim YS, Song TJ, Choi JM, Kim JI, Jun JB, Kim MY, Pyun DK, Lee HC, Jung YH. The etiology of acute viral hepatitis for the last 3 years. Korean J Med. 2005;68:256-260. |

| 20. | Keeffe EB. Occupational risk for hepatitis A: a literature-based analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:440-448. |

| 21. | Foodborne transmission of hepatitis A--Massachusetts, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:565-567. |

| 22. | O'Donovan D, Cooke RP, Joce R, Eastbury A, Waite J, Stene-Johansen K. An outbreak of hepatitis A amongst injecting drug users. Epidemiol Infect. 2001;127:469-473. |

| 23. | Jacobsen KH, Koopman JS. Declining hepatitis A seroprevalence: a global review and analysis. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132:1005-1022. |

| 24. | Hendrickx G, Van Herck K, Vorsters A, Wiersma S, Shapiro C, Andrus JK, Ropero AM, Shouval D, Ward W, Van Damme P. Has the time come to control hepatitis A globally? Matching prevention to the changing epidemiology. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15 Suppl 2:1-15. |

| 25. | Akriviadis EA, Redeker AG. Fulminant hepatitis A in intravenous drug users with chronic liver disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:838-839. |

| 26. | Pramoolsinsap C, Poovorawan Y, Hirsch P, Busagorn N, Attamasirikul K. Acute, hepatitis-A super-infection in HBV carriers, or chronic liver disease related to HBV or HCV. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1999;93:745-751. |

| 27. | Keeffe EB. Acute hepatitis A and B in patients with chronic liver disease: prevention through vaccination. Am J Med. 2005;118 Suppl 10A:21S-27S. |

| 28. | Song HJ, Kim TH, Song JH, Oh HJ, Ryu KH, Yeom HJ, Kim SE, Jung HK, Shim KN, Jung SA. Emerging need for vaccination against hepatitis A virus in patients with chronic liver disease in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:218-222. |

| 29. | Kim do Y, Ahn SH, Lee HW, Kim SU, Kim JK, Paik YH, Lee KS, Han KH, Chon CY. Anti-hepatitis A virus seroprevalence among patients with chronic viral liver disease in Korea. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:923-926. |

| 30. | Melnick JL. History and epidemiology of hepatitis A virus. J Infect Dis. 1995;171 Suppl 1:S2-S8. |

| 31. | Vento S, Garofano T, Renzini C, Cainelli F, Casali F, Ghironzi G, Ferraro T, Concia E. Fulminant hepatitis associated with hepatitis A virus superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:286-290. |

| 32. | Kang JH, Lee KY, Kim CH, Sim D. Changing hepatitis A epidemiology and the need for vaccination in Korea. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2004;22:237-242. |

| 33. | Bianco E, Stroffolini T, Spada E, Szklo A, Marzolini F, Ragni P, Gallo G, Balocchini E, Parlato A, Sangalli M. Case fatality rate of acute viral hepatitis in Italy: 1995-2000. An update. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:404-408. |

| 34. | Kyrlagkitsis I, Cramp ME, Smith H, Portmann B, O'Grady J. Acute hepatitis A virus infection: a review of prognostic factors from 25 years experience in a tertiary referral center. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:524-528. |

| 35. | Lee TH, Kim SM, Lee GS, Im EH, Huh KC, Choi YW, Kang YW. [Clinical features of acute hepatitis A in the Western part of Daejeon and Chungnam province: single center experience]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;47:136-143. |