Published online May 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i19.2450

Revised: February 15, 2011

Accepted: February 22, 2011

Published online: May 21, 2011

The therapeutic options for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have been so far rather inadequate. Sorafenib has shown an overall survival benefit and has become the new standard of care for advanced HCC. Nevertheless, in clinical practice, some patients are discontinuing this drug because of side effects, and misinterpretation of radiographic response may contribute to this. We highlight the importance of prolonged sorafenib administration, even at reduced dose, and of qualitative and careful radiographic evaluation. We observed two partial and two complete responses, one histologically confirmed, with progression-free survival ranging from 12 to 62 mo. Three of the responses were achieved following substantial dose reductions, and a gradual change in lesion density preceded or paralleled tumor shrinkage, as seen by computed tomography. This report supports the feasibility of dose adjustments to allow prolonged administration of sorafenib, and highlights the need for new imaging criteria for a more appropriate characterization of response in HCC.

- Citation: Abbadessa G, Rimassa L, Pressiani T, Carrillo-Infante C, Cucchi E, Santoro A. Optimized management of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Four long-lasting responses to sorafenib. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(19): 2450-2453

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i19/2450.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i19.2450

Therapeutic options for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have been so far inadequate[1-5]. Recent progress in molecular biology has allowed identification of new therapeutic targets, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is overexpressed and related to progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in HCC[6,7]. Sorafenib, an oral multi-kinase inhibitor, blocks tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis by targeting RAF, VEGF receptors, platelet-derived growth factor receptor β, c-KIT and FLT3 signaling pathways[8].

Efficacy and safety of sorafenib have been demonstrated by phase II/III trials, which have proven that 400 mg bid sorafenib significantly prolongs OS, reduces the risk of death by 31%, and increases the time to radiological progression[9-11]. Consequently, sorafenib has become the standard of care for patients with advanced HCC.

We present four cases of unresectable, systemic-treatment-naïve HCC, enrolled in phase II (HOPE) and III (SHARP) trials at the Department of Medical Oncology and Hematology of the Istituto Clinico Humanitas in Rozzano (Milan, Italy), who obtained long-lasting objective responses. All patients were diagnosed by histology and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Their peculiar responses and the personalized management of side effects provide suggestions to optimize the use of sorafenib in the management of HCC patients.

In December 2002, a 61-year-old caucasian man was examined by MRI, which showed a single 110 mm × 140 mm hepatic lesion and thrombosis of the main and right branches of the portal and superior mesenteric veins. The patient was Child-Pugh class A, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) 0, with α fetoprotein (AFP) of 10 ng/mL. Sorafenib treatment was started in January 2003. In February 2003, grade 2 diarrhea was controlled with loperamide. In April 2003, the lesion measured 70 mm × 66 mm; grade 3 diarrhea appeared and resolved in July 2003, after a 3-d pause from sorafenib and daily loperamide. In December 2003, persistent grade 2/3 diarrhea reappeared, and resolved after a 50% reduction in sorafenib dose. In January 2004, treatment was discontinued due to progressive disease: a new lesion appeared at the edge of the previous one. From March 2003 to January 2004, AFP values progressively increased from 20 to 218 ng/mL. The patient achieved a 70% objective response according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, and 12 mo PFS. The patient died in June 2005.

A 63-year-old caucasian man was diagnosed with hepatitis B and C virus-related cirrhosis in 1983, and with HCC in November 2002. In February 2003, at baseline, a 20 mm × 25 mm lesion in hepatic segment IV and a non-clearly definable lesion in segment II were visible. Gynecomastia, moderate thrombosis and erythema were managed, since March 2003, with periodical treatment pauses. In September 2003, sorafenib dose was reduced by 50% (400 mg/d) due to persistent grade 2 diarrhea. A minor response was detected in May 2004, and the lesion in segment IV reduced to 15 mm × 15 mm (55%) in July 2004; the lesion in segment II lost density and became undetectable on subsequent scans. In August 2005, after 30 mo on therapy, HCC disease progression was observed as an increase in the number of tumor lesions and an increase in the diameter of existing lesions. We observed progression in the liver and not at other sites. Thereafter, the patient was lost to follow-up and died in April 2008.

A 70-year-old caucasian man with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related cirrhosis, with a good PS, was diagnosed in July 2002 with vascular-invading HCC. In January 2003, at baseline, a single hepatic lesion measured 60 mm × 50 mm and AFP was 15 ng/mL. In June 2003, a 50% reduction in sorafenib dose was required due to paresthesia and cramps in the hands and feet. From July to November 2003, the lesion gradually reached 35 mm × 35 mm. At that time, the area originally covered by the lesion ranged from a denser portion, which surrounded the persistent tumor, to a less dense area, towards the normal liver. In October 2004, the lesion was barely visible. In October 2005, a complete response was achieved. AFP slightly decreased throughout the study, stabilizing at 12 ng/mL. In January 2008, after PFS of 60 mo, a new 10-mm lesion was detected in segment VIII, outside the area previously involved. The patient was treated with two chemoembolizations and he is in complete response as of July 2010.

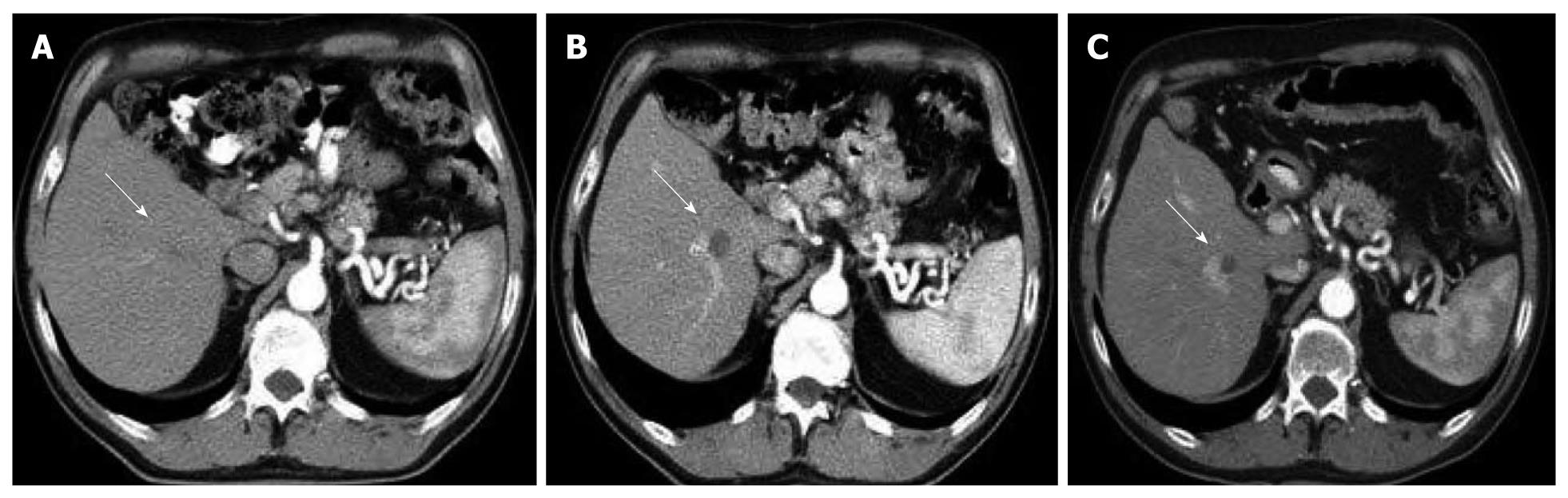

A 69-year-old caucasian man who had HCV-related cirrhosis since 1987 was diagnosed with HCC in May 2005. At baseline, in June 2005, the patient presented with three hepatic lesions, thrombosis of the portal vein main branch, Child-Pugh class A and ECOG PS 0. After 10 d on sorafenib, treatment was stopped for 1 mo due to grade 3 hand-foot skin reaction, and restarted at 50% of the dose. In September 2005, a partial response was observed, and the density of the only remaining lesion was reduced. In October 2005, the treatment was paused for 9 d due to grade 3 hand-foot skin reaction. At resolution, treatment was restarted at a dose of 400 mg every other day. In May 2007, the lesion was radiographically unchanged, was biopsied and proven disease free. As of July 2010, 62 mo from enrollment, the patient, still on the reduced dose regimen, maintains a complete response (Figure 1).

Sorafenib is the only effective systemic therapy for the treatment of HCC, but side effects lead to treatment discontinuation in some patients. Nowadays, HCC is treated by hepatologists or oncologists. The former may be less accustomed to the typical side effects of anticancer drugs, and the latter may not be keen to manage problems related to underlying liver cirrhosis. This report proves the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in the management of advanced HCC patients.

The described cases highlight how, in case of sorafenib-related side effects, reductions and pauses in the administered dose can allow long-term treatments. Efficacy of conventional cytotoxic agents is strictly related to the administered dose. With new targeted agents, length of treatment, rather than dose intensity, may be fundamental for tumor control. The winning strategy may lie in managing side effects, and tailoring the anticancer regimen to the characteristics of the patients, rather than discontinuing treatment at the appearance of signs of intolerance. Unfortunately, data on drug blood levels that are needed to achieve and maintain target inhibition are inadequate. The multi-target nature of sorafenib is one additional challenge, which means that various factors play a role in the activity of this agent[6-8].

In three of the four reported cases, objective responses were achieved following substantial dose reductions. In patient 2, partial response was observed at month 16 of the study (7 mo at full dose and 9 at half dose). In patient 3, sorafenib dose was reduced by 50% during the month 6 on treatment; an objective response was seen in month 8 of therapy, and a complete response was achieved after a total of 34 mo on study. In patient 4, sorafenib dose was reduced by 50% after just 10 d of therapy, and 20 d later, a partial response was observed. One month later, dose was further reduced to 25%, and complete response was documented after 24 mo on study. The lesson appears clear: the recommended sorafenib dose is 400 mg bid; when needed, dose reductions, by limiting side effects, offer a better quality of life and can allow long-term administration and achievement/maintenance of tumor control.

The radiological features of responding lesions are another issue worthy of attention. When assessing the efficacy of targeted therapies by imaging, a gradual change in tumor density and blood flow may be observed before tumor shrinkage. However, the uncommon radiological patterns can lead to late recognition of responses, or worse, to misleading evaluations. Indeed, in two of the reported cases (patients 3 and 4), lesions seemed unchanged and, at first sight, had been considered active. On the contrary, these lesions were responding and being substituted by residual scars (in patient 4, this was confirmed by liver biopsy). This issue deserves serious consideration and calls for new, more appropriate methods of appraisal. With targeted therapies, traditional methods of quantitative evaluation, such as WHO criteria or Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, may not be optimal, and the need for qualitative standardized measurements becomes more pressing[9,12-14]. Although positron emission tomography is not reliable for evaluation of HCC, Hounsfield unit (HU) density scale for CT scan imaging, and signal patterns for MRI can be used to measure tumor necrosis. Combination of these methods with dimensional measurements allows more precise characterization of sorafenib responses in this disease[13,14]. In our experience, a lesion density reduction to 40 HU on CT scan can be considered indicative of tumor necrosis.

An additional mean of response evaluation may be provided by analysis of blood samples. At present, there is no agreement on specific biomarkers of response to sorafenib. We analyzed routine laboratory tests and did not identify any correlation in our patients, however, we did not search for alternative signals such as markers of inflammation and oxidative stress. The recommendations that derive from the reported cases are to tailor dose and schedule, to administer the drug until progressive disease is observed, and to evaluate critically dimensional and density changes in tumor lesions. Anticancer drugs have evolved in recent years, and so should the way physicians view tumor treatment strategies. Although this calls for more personalized treatment plans, agreement on standardized and more appropriate assessment techniques will allow more conscious decision making in the treatment of advanced HCC patients[13,14].

Peer reviewer: Dr. Assy Nimer, MD, Assistant Professor, Liver Unit, Ziv Medical Centre, BOX 1008, Safed 13100, Israel

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Nagasue N, Kohno H, Chang YC, Taniura H, Yamanoi A, Uchida M, Kimoto T, Takemoto Y, Nakamura T, Yukaya H. Liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Results of 229 consecutive patients during 11 years. Ann Surg. 1993;217:375-384. |

| 2. | Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693-699. |

| 3. | Tateishi R, Shiina S, Teratani T, Obi S, Sato S, Koike Y, Fujishima T, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, Omata M. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. An analysis of 1000 cases. Cancer. 2005;103:1201-1209. |

| 4. | Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, Ayuso C, Sala M, Muchart J, Solà R. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734-1739. |

| 5. | Rimassa L, Santoro A. The present and the future landscape of treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42 Suppl 3:S273-S280. |

| 6. | Chao Y, Li CP, Chau GY, Chen CP, King KL, Lui WY, Yen SH, Chang FY, Chan WK, Lee SD. Prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and angiogenin in patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:355-362. |

| 7. | Poon RT, Lau CP, Cheung ST, Yu WC, Fan ST. Quantitative correlation of serum levels and tumor expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3121-3126. |

| 8. | Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, Wilkie D, McNabola A, Rong H, Chen C, Zhang X, Vincent P, McHugh M. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099-7109. |

| 9. | Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S, Amadori D, Santoro A, Figer A, De Greve J, Douillard JY, Lathia C, Schwartz B. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4293-4300. |

| 10. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. |

| 11. | Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25-34. |

| 12. | Ratain MJ, Eckhardt SG. Phase II studies of modern drugs directed against new targets: if you are fazed, too, then resist RECIST. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4442-4445. |

| 13. | Llovet JM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bruix J, Kramer BS, Lencioni R, Zhu AX, Sherman M, Schwartz M, Lotze M, Talwalkar J. Design and endpoints of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:698-711. |

| 14. | Horger M, Lauer UM, Schraml C, Berg CP, Koppenhöfer U, Claussen CD, Gregor M, Bitzer M. Early MRI response monitoring of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma under treatment with the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:208. |