Published online May 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i18.2302

Revised: September 26, 2010

Accepted: October 3, 2010

Published online: May 14, 2011

AIM: To evaluate double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) in post-surgical patients to perform endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and interventions.

METHODS: In 37 post-surgical patients, a stepwise approach was performed to reach normal papilla or enteral anastomoses of the biliary tract/pancreas. When conventional endoscopy failed, DBE-based ERCP was performed and standard parameters for DBE, ERCP and interventions were recorded.

RESULTS: Push-enteroscopy (overall, 16 procedures) reached enteral anastomoses only in six out of 37 post-surgical patients (16.2%). DBE achieved a high rate of luminal access to the biliary tract in 23 of the remaining 31 patients (74.1%) and to the pancreatic duct (three patients). Among all DBE-based ERCPs (86 procedures), 21/23 patients (91.3%) were successfully treated. Interventions included ostium incision or papillotomy in 6/23 (26%) and 7/23 patients (30.4%), respectively. Biliary endoprosthesis insertion and regular exchange was achieved in 17/23 (73.9%) and 7/23 patients (30.4%), respectively. Furthermore, bile duct stone extraction as well as ostium and papillary dilation were performed in 5/23 (21.7%) and 3/23 patients (13.0%), respectively. Complications during DBE-based procedures were bleeding (1.1%), perforation (2.3%) and pancreatitis (2.3%), and minor complications occurred in up to 19.1%.

CONCLUSION: The appropriate use of DBE yields a high rate of luminal access to papilla or enteral anastomoses in more than two-thirds of post-surgical patients, allowing important successful endoscopic therapeutic interventions.

- Citation: Raithel M, Dormann H, Naegel A, Boxberger F, Hahn EG, Neurath MF, Maiss J. Double-balloon-enteroscopy-based endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in post-surgical patients. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(18): 2302-2314

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i18/2302.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i18.2302

With the technique of push-and-pull enteroscopy by a double balloon endoscope, it is possible to advance much deeper into the small intestine than using a conventional push-enteroscope[1-3]. Double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) has been successfully applied for diagnosis and treatment of various small intestinal diseases, such as mid-gastrointestinal bleeding, polyposis syndromes, Crohn’s disease, lymphoma, foreign body impaction, or other inflammatory or neoplastic diseases in the jejunum or ileum[1-3]. Although the introduction of DBE by Yamamoto has brought a significant benefit for the management of various small intestinal diseases, its value in the diagnosis and treatment of biliary or pancreatic diseases in patients after complex abdominal or bilio-pancreatic surgery has recently been reported in some case studies of selected patients[4-10]. The emerging role of DBE in postoperative endoscopic procedures arises from the fact that conventional endoscopy using side viewing endoscopes, forward viewing push-enteroscopes, or (pediatric) colonoscopes has often been reported to be unsatisfactory in patients after partial or total gastrectomy (Billroth II gastrojejunostomy, Roux-en-Y reconstruction), Whipple resection or bilio-pancreatic reconstructions (pancreaticojejunostomy, choledocho-choledochostomy, hepaticojejunostomy)[4,5,10-12]. For example, in the pre-DBE era, conventional endoscopic access to the afferent loop and/or choledocho-, hepatico- or pancreaticojejunostomy was extremely difficult because of various lengths of bowel to be traversed, unfortunate locations of low jejunal anastomoses, jejunal loops of differing lengths, fixed jejunal loops, angulation or postoperative strictures and changes[4,5,10-12].

Failure of endoscopic access and therapy in post-surgical patients with normal papilla, choledocho-, hepatico- or pancreaticojejunostomy often results in more invasive and cost-intensive procedures such as percutaneous transhepatic cholangiodrainage (PTCD), computed tomography (CT)-guided pancreatic drainage, or repeated surgery. A training model for balloon-assisted enteroscopy and hepatobiliary interventions has been established by our group to learn, facilitate and adequately perform modern enteroscopic interventions[13-17]. Therefore, this study describes our clinical results from the prospective use of DBE in performing cholangio- and pancreatography, including therapeutic interventions of the biliary and pancreatic tract in a group of 37 consecutive post-surgical patients.

Between August 2005 and December 2008, 45 consecutive patients after complex abdominal surgery were admitted to the Department of Medicine 1 of the University Erlangen-Nürnberg because of abdominal pain, cholestasis, inflammatory symptoms, cholangitis, choledocholithiasis, or for an enlarging pancreatic pseudocyst. During this study period, eight patients with partial gastrectomy (Billroth II) and both afferent and efferent loops at the gastrojejunostomy were excluded from the study, because six could initially be successfully treated using the treatment gastroscope and two using the side-viewing duodenoscope.

Thirty-seven consecutive post-surgical patients were included in this study after having obtained informed consent and agreement to participate and for scientific documentation of the examination results. This clinical trial was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki declaration. The different indications for ERCP, previous surgery, localization of foot-point anastomosis, and depth of papilla or ostium localization are listed in Tables 1 and 2. In this prospective protocol, all patients underwent first usual, conventional endoscopy at least once using esophago-gastroduodenoscopy (GIF-Q160, GIF-1T140; Olympus, Hamburg, Germany), side-viewing duodenoscopy (TJF160; Olympus) and push-enteroscopy (PE; SIF Q140; Olympus) to exclude other diseases and to document postoperative anatomy, type of surgery, depth of anastomoses and, if possible, of papilla or biliary or pancreatic enteroanastomoses. Thirteen percent of all patients had two PEs in order to clarify the post-surgical situation and to reach the entero-anastomosis.

| Pts. | Age/sex | Indication | Previous surgery | Access by G/T/P |

| 1 | 72 f | Recurrent cholangitis | LTX, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| 23 | 76 m | Malignant cholestasis | Partial gastrectomy (BII) | No |

| 3 | 60 m | Liver abscesses | Whipple resection, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | P |

| 4 | 66 m | Benign cholestasis | CHE, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | P |

| 53 | 52 f | Benign cholestasis | Complicated CHE, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostom | No |

| 6 | 79 f | Postsurgical bile duct leakage | Complicated CHE partial gastrectomy (BII) | P |

| 7 | 38 m | Recurrent cholangitis | Congenital bile duct atresia Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| 8 | 66 m | Pancreatitis with pseudocyst | Pylorus preserving pancreatic head resection, Roux Y, hepatico-& pancreaticojejunostomy | No |

| 9 | 58 f | Benign cholestasis abdominal pain | Total gastrectomy, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| 10 | 64 f | Benign cholestasis with cholangitis | CHE, right hemihepatectomy, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| 11 | 50 f | Benign cholestasis, bile ducht stones | Dorsal gastroenterostomy with hepaticojejunostomy | G1 |

| 12 | 51 f | Benign cholestasis | CHE, partial gastrectomy (BII) with Roux Y | No |

| 13 | 81 f | Malignant cholestasis | CHE, partial gastrectomy (BII) with Roux Y | No |

| 143 | 52 f | Benign cholestasis | Compliated CHE, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| 153 | 71 m | Malignant cholestasis | Complicated CHE, partial gastrectomy (BII), Roux Y | No |

| 16 | 69 f | Recurrent cholangitis | CHE, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| 17 | 47 f | Cholangitis, malignant cholestasis | Total gastrectomy, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostom | T2 |

| 18 | 67 m | Benign cholestasis | LTX, bile duct revision, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| 19 | 51 f | Benign cholestasis, bile ducht stones | LTX, bile duct revision, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| 20 | 68 f | Benign cholestasis, chronic pancreatitis | Total gastrectomy, Roux Y | No |

| 21 | 71 m | Recurrent cholangitis | Modified Whipple resection, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| 22 | 68 m | Malignant cholestasis | Partial gastrectomy (BII) with Roux Y | No |

| 233 | 64 f | Malignant cholestasis | CHE, small bowel & colon resection, Roux Y, hepatico-jejunostomy | No |

| 24 | 61 m | Suspected malignant cholestasis | Modified Whipple resection, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| 25 | 62 m | Malignant cholestasis | Total gastrectomy, Roux Y | P |

| 26 | 73 m | Benign cholestasis | Pylorus preserving pancreatic head resection, Roux Y, hepatico& pancreaticojejunostomy | No |

| 27 | 76 m | Benign cholestasis | Total gastrectomy, Roux Y | No |

| 283 | 76 f | Malignant cholestasis | Total gastrectomy, Roux Y | No |

| 29 | 84 m | Malignant cholestasis | Partial gastrectomy (BII) with Roux Y | No |

| 30 | 54 m | Choledocholithiasis, cholangitis | Complicated CHE, Roux Y, choledochojejunostomy | No |

| 31 | 74 m | Choledocholithiasis | Total gastrectomy, Roux Y | No |

| 32 | 61 m | Recurrent cholangitis | LTX, bile duct revision, Roux Y, choledochojejunostomy | P |

| 333 | 55 m | Suspected malignant cholestasis, chronic pancreatitis | Whipple resection, Roux Y, hepatico- & pancreatico-jejunostomy | No |

| 34 | 34 f | Biliary colics, benign cholestasis hepatitis C | LTX, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | P |

| 353 | 64 m | Suspected malignant cholestasis, chronic pancreatitis | Whipple resection, Roux Y, hepatico- & pancreatico-jejnostomy | No |

| 36 | 51 f | Suspected choledocholithiasis,right abdominal pain | LTX, Roux Y, choledochojejunostomy | No |

| 37 | 61 m | Recurrent cholangitis | Complicated CHE, Roux Y, hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| Pts. | Foot-point anastomosis (cm) | Papilla/ostium (cm) | ERCP diagnosis | PTCD before/after DBE |

| 1 | 84 | 162 | Stenotic hepaticojejunostomy (mucosal and intramural stricture 3 mm), putrid cholangitis | (2) Yes |

| 21 | 67 | Not found | Swelling of anastomosis, afferent loop not found | No |

| 3 | 65 | 90 | Stenotic hepaticojejunostomy (mucosal, 11 mm stricture), cholangitis | No |

| 4 P | 75 | 110 | Sludge, stenotic hepaticojejunostomy (mucosal, 3 mm stricture) | No |

| 51 | Not found | PTCD stenotic hepaticojejunostomy (12 mm stricture) | (8) Yes(6) | |

| 6 P | 52 (BII) | 78 | Distal bile duct leakage and adhesion to abd. drainage | No |

| 7 | 80 | 165 | Stenotic hepaticojejunostomy (mucosal, 2 mm stricture), cholangitis | No |

| 8 | 85 | 107 | Normal choledochojejunostomy pancreaticojejunostomy with 10 mm diameter, 10 mm pancreatic | No |

| 85 | 118 | Duct stricture, pancreatic pseudocyst | ||

| 9 | 85 | 130 | Normal hepaticojejunostomy, bile duct kinking | No |

| 10 | 77 | 142 | Stenotic hepaticojejunostomy (intramural, 4 mm) and stricture, common hepatic duct 4mm, bilioma | No |

| 11 | 46 | 62 | Obstructed hepaticojejunostomy by sludge/stones (hepaticolithiasis) | No |

| 12 | 70 | 105 | Papilla stenosis, bile duct kinking and stricture 3 mm | No |

| 13 | 60 | 84 | Bile duct stricture 18 mm due to papilla tumor | Yes (2) |

| 141 | 95 | Not found | PTCD stenotic hepaticojejunostomy (12 mm stricture) | (12) Yes (6) |

| 151 | 57 | 110 | PTCD edematous, tumorous papilla | Yes (2) |

| 16 | 65 | 120 | Stenotic hepaticojejunostomy (mucosal, 4 mm stricture) | (10) Yes |

| 17 | 65 | 92 | Malignant proximal bile duct stricture 22 mm | No |

| 18 | 100 | 175 | Hepaticolithiasis, normal hepaticojejunostomy | No |

| 19 | 70 | 120 | Stenotic hepaticojejunostomy (intramural, 12 mm stricture), cholestasis due to bile duct bleeding | (1) Yes |

| 20 | 60 | 78 | Papilla & bile duct stenosis due to chronic, pancreatitis, pancreatic duct stenosis | No |

| 21 | 55 | 85 | Stenotic hepaticojejunostomy,(mucosal, 2 mm stricture) & intrahepatic stricture | No |

| 22 | 75 | 110 | Distal bile duct stricture 45 mm due to ampullary tumor | No |

| 231 | Not found | PTCD complete malignant stricture of hepaticojejunostomy due to progredient metastasis | Yes (1) | |

| 24 | 60 | 120 | Hilar and hepatic duct strictures 9 and 26 mm, normal hepatico jejunostomy | No |

| 25 P | 65 | 110 | Malignant obstruction biliary metal stent, sludge, cholangitis | (4) Yes |

| 26 | 110 | 158 | Stenotic hepaticojejunostomy, (intramural, 10 mm stricture) | No |

| 27 | 76 | 112 | 22 mm bile duct stricture due to chronic pancreatitis | (2) Yes |

| 281 | 88 | 145 | Polypoid papilla tumor | Yes (4) |

| 29 | 100 | 140 | Distal bile duct stricture 35mm due to suspected pancreatic tumor | No |

| 30 | 105 | 151 | Bile duct with sludge, normal choledochojejunostomy | No |

| 31 | 51 | 165 | Choledocholithiasis | (2) Yes (2) |

| 32 P | 78 | 147 | Stenotic choledochojejunostomy, (intramural, 6 mm stricture) and bilioma segment IV | No |

| 331 | 66 | Not found 126 | PTCD: malignant stenotic hepatico-jejunostomy (filia), but normal pancreaticojejunostomy and chronic pancreatitis - | Yes (3) |

| 66 | ||||

| 34 P | 80 | 132 | Stenotic hepaticojejunostomy & hilar stenosis in ischemic cholangiopathy | No |

| 351 | 68 | 114 | PTCD: recurrence of pancreatic tumor with malignant stenosis at hepaticojejunostomy, bile ducts and small intestine normal pancreaticojejnostomy and chronic pancreatitis | Yes (5) |

| 68 | 131 | |||

| 36 | 70 | 131 | Normal choledochojejunostomy | No |

| 37 | 78 | 139 | Stenotic hepaticojejunostomy (mucosal 2mm stricture) | No |

If this approach by conventional endoscopy failed to gain access to the papilla, the ostium of the bilio-digestive or pancreatico-digestive anastomosis, push-and-pull enteroscopy (DBE, EN-450T5; Fujinon Europe, Willich, Germany) was tried before admitting the patient for re-operation, CT-guided drainage or PTCD. Among these DBE examinations, the p-type enteroscope (EN-450P5/20; Fujinon Europe) was used in 13.7% and the t-type enteroscope (EN-450T5) in 86.2% of the patients.

All enteroscopic procedures were performed during conscious sedation (midazolam/pethidine or propofol/pethidine) by two experienced examiners (> 1500 ERCP) and two endoscopy assistants. Butylscopolamine was only used after reaching the end of the afferent loop for ERCP or at withdrawal of the enteroscope, respectively, in cases of vigorous peristalsis, to identify postoperative anatomy, hidden ostium or to facilitate cannulation of the ostium of the biliodigestive anastomosis.

PE was started in the left lateral position using the Olympus SIF-Q140 forward-viewing enteroscope (working length 2.50 m, no elevator lever) without overtube[18]. If PE failed to come forward, the patient was turned to the prone position and X-rays were used to localize loops, to straighten the enteroscope, to direct manual compression to guide the enteroscope forward, or to minimize pain by adequate withdrawal of the enteroscope[18-21]. Post-surgical anatomy, location of the foot-point anastomosis and the route to the afferent loop were each exactly documented, as well as time requirements for each diagnostic and therapeutic step. Foot-point anastomosis and the afferent loop were marked by India ink. Forward-viewing PE-based ERCP was performed using the typical ERCP technique as described previously[18-21].

DBE was performed using a standard technique, starting in the left lateral position, and thereafter changing to the prone position as described by Yamamoto and other authors[1-4]. At times, manual compression to guide the enteroscope in the abdomen and radiography were necessary. Provided that the anatomical situation and access to papilla or ostium of the enteroanastomoses were clarified, the afferent loop in proximity to the foot-point anastomosis was marked with clips and Indian ink on retraction of the enteroscope, so that this location would be found quicker in a future examination. Using a standardized protocol, the advance was exactly documented during DBE, and the respective anatomical depth of foot-point anastomosis, and papilla and ostium region were determined with the retracted and (as much as possible) straightened enteroscope. The time taken for this procedure and the whole procedure were also recorded. If during enteroscopy, advance failed, the enteroscope slid back, or if pain was experienced by the patient, radiography was applied to avoid kinking, to straighten loops and to retract the enteroscope carefully.

When papilla or pancreatico-, choledocho-, or hepaticojejunostomy were needed, ERCP was applied using the push-and-pull enteroscope, a forward-viewing endoscope of 2 m working length, without elevator lever[19-21]. This was assisted by X-rays for radiographic imaging of bile ducts and/or pancreatic ducts or a pancreatic cyst. Appropriate stabilization of the enteroscope with the overtube and/or enteroscope balloon was often required before performance of ERCP.

After administration of contrast medium and diagnosis, papillotomy or, an initial bougienage and/or incision of a stenotic ostium of the hepaticojejunostomy was performed. This was achieved by the use of a 5 and 6 Fr Huibregtse catheter and/or a 6 Fr papillotome (Olympus, intended for SIF Q140 enteroscope), or a snare. Further interventions aided by a 5-m guide wire (Metro guide wire; Cook, Limerick, Ireland) were implantation of endoprostheses (5-8 Fr) or of biliary 7 Fr nasobiliary probes, stone removal, or ostium and papilla dilation using either a CRE-dilation balloon (CRE 8-10mm balloon; Cook) or a basket.

With regard to prosthesis change, the old prosthesis was at first mobilized with a foreign-body forceps or a loop, and extracted and placed in the afferent loop. After DBE-ERCP implantation of the new prostheses was completed, the old prostheses were fixed again with the loop and extracted from the patient during the final retraction of the double balloon enteroscope.

During the period between August 2005 and December 2008, 45 post-surgical patients were admitted to hospital for endoscopy. Eight of these patients with partial gastrectomy (Billroth II, without Roux-en-Y reconstruction) could initially be successfully treated with gastroduodenoscopy or side-viewing duodenoscopy alone, and were therefore excluded from the prospective study. In the remaining 37 patients with complex abdominal surgery, neither a gastroscope nor duodenoscope gained initial access to the papilla or ostium, such that PE, and if it failed, then DBE were necessary.

Previous abdominal surgery of the remaining 37 patients (Table 1) was partial gastrectomy in eight patients (Bilroth II-resection, 21.6%, four patients had further resections after B-II-resection, five patients with Roux-en-Y reconstruction); total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y loop in seven patients (18.9%), and classical or modified Whipple operation with Roux-en-Y loop in seven patients (18.9%). Fifteen patients had normal stomach anatomy after biliary surgery with reconstruction of a choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomy via Roux-en-Y loop (40.5%).

Thus, 34 patients had previously undergone Roux-en-Y construction (91.8%), whereas only three had an end-to-side gastrojejunostomy that contained an afferent and efferent loop (8.1%).

Among all post-surgical patients, 24/37 patients (64.8%) had a final diagnosis of choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomy (23 Roux-en-Y, one dorsal gastrojejunostomy), while 13 patients (35.1%) still had a normal papilla. The pancreaticojejunostomy had to be searched additionally in only three of these patients (8.1%) (Table 2).

With regard to the indication, it was necessary to radiograph the bile ducts of 34 patients (91.8%), because these patients were admitted for cholestasis (59.3%), cholangitis (28.1%), or choledocholithiasis (13.3%), with a view to PTCD or re-operation. Radiography of the pancreatic duct was required in only three patients (8.1%), because of the presence of a pancreatic pseudocyst and suspected or advanced chronic pancreatitis, respectively (Table 1).

Due to the complex anatomical situation in seven patients (18.9%) with recurrent disease, 37 PTCDs had already been performed in these individuals before the introduction of DBE-ERCP (Table 2).

The individual endoscopic accessibility and anatomical depth of the anastomoses, as well as of the papilla and the ostium of the choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomy and of the pancreaticojejunostomy using PE and DBE are described in Tables 1 and 2. The average depth of all anastomoses (three Billroth II gastrojejunostomy, 34 foot-point anastomoses jejunojejunostomy) was 71 ± 21 cm, and the length of the afferent loop to the papilla or enteroanastomosis measured a further 53 ± 26 cm.

In total, a median of four (2-19, 25th-75th percentile) balloon-assisted enteroscopic cycles had to be performed after the passage of the anastomosis in the afferent loop, until the papilla or ostium were reached by DBE. Manual compression to guide the enteroscope was necessary in most patients.

The push-enteroscope could reach the papilla or the enteroanastomoses in only 6/37 cases (16.2%), while DBE had to be applied in 31 post-surgical patients (83.7%).

With DBE, access to papilla, choledocho-, hepatico- or pancreaticojejunostomy could be successfully and repeatedly achieved in 23 out of 31 patients (74.1%).

A total of 86 DBE-ERCPs were undertaken in those 31 patients, who failed to be successfully examined by PE. Seventy-five of the 86 DBE examinations (87.2%) were successfully carried out as a diagnostic or therapeutic DBE-ERCP (Tables 1-3), while 11 examinations (12.7%) in eight patients were unsuccessful.

| Pts. | Push ERCP-/DBE-ERCP | Sedation | X-ray | Procedure Time (min) | |||

| Procedures | Therapy | Dose (mg) | Drug | Time (min) | Dose (103 cGy/cm2) | ||

| 1 | 7 | Ostium incision (snare, papillotome) dilation, 2 stents inserted, regular change of 2 stents/1 yr | 12.8 ± 3 132 ± 31 | Midazolam Pethidine | 19 ± 11 | 3.4 ± 2 | 122 ± 158 |

| 2 | 1 | Not successful, re-operation | 10.0 | Midazolam | 3.3 | 1.0 | 82 |

| 100 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 120 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 3 P | 3 | Ostium incision (papillotome), dilation, stent insertion, regular change of stent/1 yr | 15.0 ± 1 | Midazolam | 7.5 ± 7 | 1.8 ± 1.9 | 115 ± 79 |

| 125 ± 35 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 40 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 4 P | 4 | Stent insertion, regular change of stent/1 yr | 12 ± 2 | Midazolam | 20 ± 29 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 110 ± 171 |

| 137 ± 25 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 5 | Diazepam | ||||||

| 5 | 2 | Not successful, PTCD | 12 ± 1 | Midazolam | 2.8 ± 1 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 77 ± 11 |

| 150 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 5 | Diazepam | ||||||

| 40 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 6 P | 2 | Stent insertion, closure of bile duct leakage | 7.8 ± 0.4 | Midazolam | 4.0 ± 1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 135 ± 71 |

| 100 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 7 | 9 | Ostium incision (papillotome), 2 stents inserted, regular change of stents/1 yr | 1691 ± 867 | Propofol | 7.1 ± 6 | 1.8 ± 2.4 | 168 ± 131 |

| 135 ± 74 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 40 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 8 | 4 | Bougienage pancreaticojejunostomy, stent insertion into pancreatic duct and pseudocyst; normal hepatico-jejunostomy | 13.3 ± 2 | Midazolam | 11.8 ± 9 | 2.0 ± 2 | 161 ± 92 |

| 158 ± 38 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 40 ± 28 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 9 | 1 | Normal hepaticojejunostomy | 14 | Midazolam | 10.1 | 0.5 | 91 |

| 150 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 10 | 4 | 3 stents inserted, one change of 2 stents | 11.2 ± 5 | Midazolam | 12.6 ± 9 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 61 ± 12 |

| 133 ± 28 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 11 | 4 | Insertion nasobiliary probe, dilation, stone extraction, insertion of stent | 9.5 ± 1 | Midazolam | 8.1 ± 2 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 61 ± 22 |

| 125 ± 35 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 20 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 12 | 8 | Bougienage, papillotomy, papilla dilation 8-10mm, stent insertion, regular change of stents/18 months | 1082 ± 476 | Propofol | 14 ± 8 | 3.1 ± 1.8 | 113 ± 97 |

| 156 ± 77 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 47 ± 11 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 13 | 3 | Stent insertion, regular change of stent unsuccessful due to progredient papilla tumor, PTCD | 10.8 ± 3 | Midazolam | 13 ± 4 | 5.9 ± 2.9 | 177 ± 61 |

| 91 ± 52 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 40 ± 28 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 14 | 2 | Not successful, PTCD | 25 ± 7 | Midazolam | 5.4 ± 1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 155 ± 21 |

| 175 ± 35 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 15 | 2 | Not successful, PTCD | 7.8 ± 3 | Midazolam | 5.9 ± 2 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 122 ± 46 |

| 100 ± 25 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 40 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 16 | 1 | Ostium incision (papillotome), 2 stents inserted (perforation) | 14 | Midazolam | 15.7 | 1.7 | 155 |

| 150 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 5 | Diazepam | ||||||

| 17 | 5 | Papillotomy*, bougienage, nasobiliary probe; insertion of 2 stents, regular change of 2 stents/9 mo | 16.8 ± 4 | Midazolam | 11.6 ± 11 | 2.5 ± 2.6 | 198 ± 98 |

| 210 ± 74 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 16.7 ± 10 | Diazepam | ||||||

| 30 ± 11 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 18 | 1 | Stone extraction | 19 | Midazolam | 24.4 | 5.3 | 178 |

| 200 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 19 | 4 | Extraction sludge & blood coagel, insertion nasobiliary probe, extraction of percutaneous drainage & insertion of 2 stents (rendezvous), regular change of 2 stents/ 9 mo | 13 ± 1 | Midazolam | 9.7 ± 9 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 82 ± 31 |

| 116 ± 28 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 5 ± 5 | Diazepam | ||||||

| 20 | 4 | Papillotomy, stent insertion pancreatic duct, regular change of stent/6 mo, hemostasis with injection therapy | 695 ± 275 | Propofol | 8.7 ± 1 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 61 ± 13 |

| 75 ± 50 | PSSSethidine | ||||||

| 70 ± 14 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 21 | 3 | Insertion of 2 stents, regular change of 2 stents/6 mo | 12 ± 1.8 | Midazolam | 15 ± 7 | 4.5 ± 1.9 | 185 ± 32 |

| 158 ± 62 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 22 | 1 | Papillotomy, insertion of 2 stents | 19 | Midazolam | 17.2 | 4.5 | 113 |

| 200 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 40 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 23 | 1 | Not successful, PTCD | 16 | Midazolam | 0.6 | 0.2 | 63 |

| 50 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 20 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 24 | 2 | Stent insertion | 17.5 ± 2 | Midazolam | 18.9 ± 15 | 5.6 ± 2.8 | 150 ± 61 |

| 100 ± 70 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 25 P | 3 | Stone/sludge extraction, dilation, biliary metal stent and malignant bile duct stricture, stent insertion, regular change of stent/9 mo | 9 ± 4 | Midazolam | 12.9 ± 2 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 54 ± 12 |

| 200 ± 65 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 26 | 2 | Ostium incision (papillotome), bougienage, stent insertion | 7 ± 4 | Midazolam | 4.5 ± 2 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 61 ± 23 |

| 75 ± 35 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 40 ± 20 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 27 | 3 | Papillotomy, extraction of percutaneous drainage and insertion of 2 stents (rendezvous) | 5.7 ± 1 | Midazolam | 5.0 ± 1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 71 ± 12 |

| 83 ± 28 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 40 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 28 | 1 | Not successful, PTCD | 5 | Midazolam | 2.1 | 0.6 | 109 |

| 50 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 29 | 2 | Papillotomy, bougienage, stent insertion | 9 ± 2 | Midazolam | 9.2 ± 2 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 113 ± 21 |

| 150 ± 25 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 30 | 1 | Sludge extraction, insertion nasobiliary | 2.5 | Midazolam | 16.4 | 7.8 | 123 |

| 50 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 31 | 2 | Papillotomy, stone extraction, extraction of percutaneous drainage and insertion of stent (rendezvous) | 7 ± 2 | Midazolam | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 96 ± 31 |

| 100 ± 25 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 80 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 32 P | 1 | Stent insertion | 10 | Midazolam | 27.1 | 7.9 | 161 |

| 200 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 20 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 33 | 2 | Not successful, PTCD diagnostic pancreatography, extraction of percutaneous drainage with both ostium incision and insertion of 2 stents (rendezvous) | 12 ± 5 | Midazolam | 10.6 ± 9 | 3.3 ± 2.5 | 97 ± 80 |

| 150 ± 70 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 40 ± 28 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 34 P | 3 | Insertion of 2 stents, regular change of stents/12 mo | 10 ± 7 | Midazolam | 19.9 ± 10 | 3.6 ± 2.3 | 98 ± 33 |

| 183 ± 124 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 10 ± 5 | Diazepam | ||||||

| 20 ± 20 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 35 | 1 | Not successful, PTCD diagnostic pancreatography | 11 | Midazolam | 0.3 | 0.1 | 86 |

| 150 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 40 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 36 | 1 | Normal choledochojejunostomy | 7 | Midazolam | 2.1 | 1.8 | 51 |

| 50 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 20 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 37 | 1 | Ostium incision (papillotome), insertion of 2 stents | 8.5 | Midazolam | 4.4 | 2.0 | 72 |

| 150 | Pethidine | ||||||

| Pts overall | Total number PE/DBE | Mean sedation dose per examination | Total x-ray time | Total x-ray dose | Total examination time | ||

| 37 | 16 PE 86 DBE | 11.7 ± 2.8 | Midazolam | 9.0 ± 5.5 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 111 ± 54 | |

| 124 ± 45 | Pethidine | ||||||

| 20 ± 20 | Butylscopolamine | ||||||

| 1156 ± 593 | Propofol | ||||||

After the initial, successful DBE-ERCP in two patients, the papilla and ostium of the hepaticojejunostomy, respectively, could be reached afterwards with the side-viewing endoscope or gastroscope. However, both treatments only worked after previous DBE, during which a large caliber overtube (17 mm, length 110 cm; Fujinon Europe) was inserted as a guide bar and the hepaticojejunostomy, located in an intestinal loop, was made visible through an inserted prosthesis.

In 8/31 patients (25.8%), despite DBE application, access to the bile ducts could not be achieved for a number of reasons (Tables 1 and 2): the anastomosis region was considerably swollen (one patient) or not visible because of metastasis (one patient); the afferent loop was technically not intubatable (one patient); the papillary or ostial region was infiltrated or covered by a tumor (four patients); or the ostium of the hepaticojejunostomy could not be found (one patient). Seven of these 8 patients (87.5%) underwent subsequent PTCD or surgery (one patient, 12.5%).

In choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomies, 14 out of 24 (58.3%) were cicatricially changed, three were infiltrated by malignant tissue (12.5%), and seven (29.1%) appeared normal in width and were intact (Table 2).

DBE was able to achieve access to 15 of the 24 choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomies (62.5%), while PE reached only four out of 24 (16.6%), and the remaining five patients with failure of the enteroscopic approach (20.8%) had to undergo PTCD.

Among the seven normal appearing ostium of the choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomies (29.1%), sludge and concrements had to be removed from one normal choledocho- and three normal hepaticojejunostomies in one patient suffering from cholangitis and choledocholithiasis, and three patients with hepaticolithiasis, respectively. In addition, endoprosthesis and/or nasobiliary probe insertion via the normal choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomy were necessary in two of these patients and in one with hilar and hepatic duct strictures, respectively.

Out of three tumor-induced malignant ostium stenoses (12.5%), the precise location of the enteroanastomosis could be identified twice, but in neither case could the stenosis be passed by a flexible hydrophilic guidewire and successfully treated. All three patients with tumorous hepaticojejunostomies required PTCD.

Eight patients out of 14 (57.1%) with cicatricial ostial stenosis at the choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomy were treated successfully via DBE-ERCP, and a further four via PE (28.5%), while the remaining two patients (14.2%) required PTCD (Tables 2 and 3).

In one case with stenotic hepaticojejunostomy and previous PTCD (suspected hepaticolithiasis) at an outlying hospital, DBE-ERCP revealed blood in the afferent loop, bile duct bleeding from PTCD, and obstruction of the stenotic ostium including bile ducts due to blood clots. Thus, extraction of sludge and blood clots was performed, and insertion of a temporary nasobiliary drainage for irrigation of the bile duct. Then, after 3 d, a first DBE-based rendezvous technique was applied via the PTCD with successful extraction of the percutaneous drainage and endoscopic insertion of two internal stents.

Of note, a successful rendezvous technique was further achieved in three patients with non-malignant disease who were admitted to our hospital after construction of a PTCD, and in one patient with initial failure of DBE (Table 3). Thus, these four patients had most significant benefit from DBE-ERCP because they had endoscopically inserted endoprotheses and lost their percutaneous drainage within 1 wk.

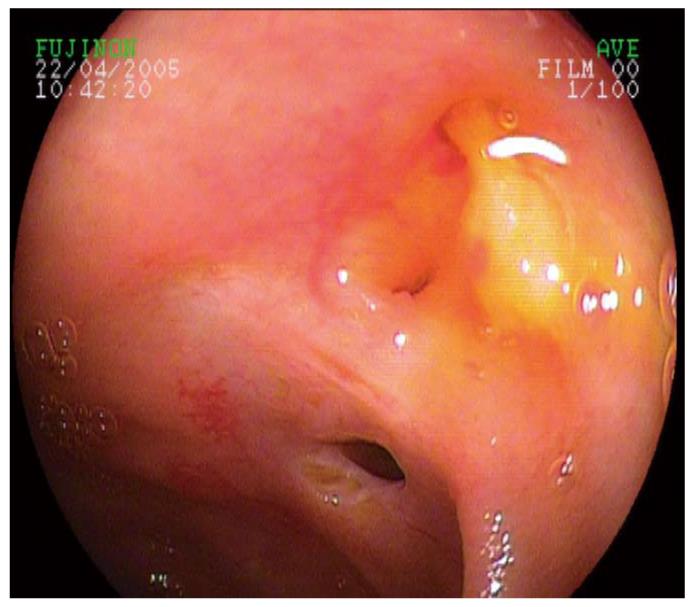

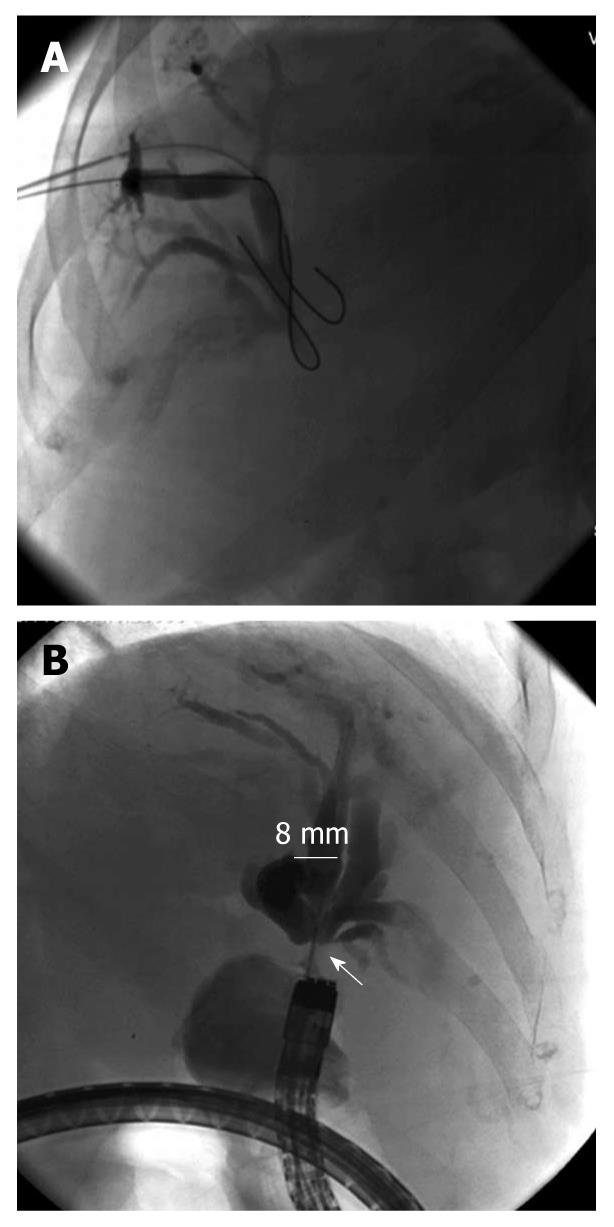

Initial endoscopic interventions at the non-malignant post-surgical biliary anstomosis (choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomy), which could not be cannulated by a flexible guidewire, included a careful, 1-3-mm ostium incision (by snare and/or 6 Fr papillotome) of each narrowed ostium in 6 out of 12 cases (50.0%) during DBE-ERCP. Five ostial incisions were made during DBE-ERCP, and one during PE-based ERCP. All incisions resulted in significant widening of the ostium with subsequent successful cannulation and intervention in the biliary system. Perforation occurred in one of the 5 patients treated with ostial incision by DBE-ERCP (20.0%), which had to be treated surgically. None (0%) of the ostial incisions caused relevant bleeding, but in two cases (40.0%), pus was discharged from the opened ostium (Figures 1 and 2).

The other six patients (50.0%) with post-surgically strictured choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomy were initially cannulated using a guidewire and were treated either with a bougienage via a papillotome or nasobiliary probe, to widen the ostium ready to implant subsequently a prosthesis, or by dilation using a colonic CRE balloon.

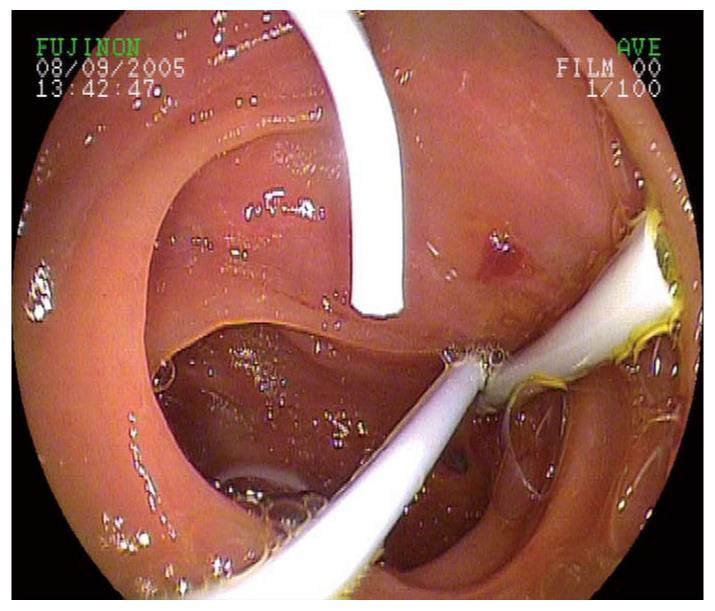

Overall, in patients with cicatricial changed choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomies, on average 1.5 ± 0.7 endoprostheses were implanted per DBE-ERCP examination (one double pigtail 5 Fr, 18 double pigtail 7 Fr and three double pigtail 8 Fr, as well as four straight 7 Fr endoprostheses and two 7 Fr nasobiliary probes; Figure 3).

At present, four patients with cicatricially changed ostium of the choledocho- and hepaticojejunostomy were treated several times by DBE-ERCP over a period of 1 year, with a regular exchange of prostheses every 3 mo (Table 3). After prosthesis implantation, all four patients had no further problems with cholangitis and cholestasis. In three out of four patients (75%), a sufficient widening of the ostium was achieved after the 1-year prosthesis therapy. Consequently, prosthesis therapy was no longer required and the cholestasis parameters stayed within the normal range over a prolonged period of time. However, the prosthesis exchange proved to be more difficult than the initial prosthesis implantation, because this procedure carries varying degrees of difficulty. In addition, an average treatment time of 12 ± 41 min had to be calculated for prostheses extraction and their temporary placing in the intestines.

Among the 31 post-surgical patients, pancreaticojejunostomy was also found via DBE in three patients (9.6%) because of recurrent abdominal pain, inflammatory symptoms and an expanding cystic lesion in the pancreatic region. This could only be achieved successfully by DBE (Tables 1 and 2). The pancreaticojejunostomies (mean insertion depth: 128 ± 7 cm) were located mostly at 3-8 cm aborally of the biliodigestive anastomosis, and hence, required 1 ± 1.7 balloon-assisted cycles more to identify the pancreaticojejunostomy and to stabilize the DBE in front of it.

During the DBE-based pancreatography, two duct systems in patients with recurrent pancreatic tumor presented a similar appearance to those with chronic pancreatitis (clotted side branches, duct irregularities, but no acute strictures). In addition, one significantly dilated residual pancreatic duct was detected merging into a cystic lesion (pseudocyst). In the latter case, for the first time a 7 Fr double pigtail prosthesis had to be inserted for drainage of the pseudocyst via DBE-ERCP, because the patient suffered evidently from pain, weight loss, and inflammatory symptoms. After 2 d, the patient was free of symptoms. However, a mild lipase increase occurred post-interventionally, but there was no manifestation of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Within a week, the pseudocyst regressed noticeably, which was sonographically controlled and later documented with endoscopic ultrasound and CT. The prosthesis was removed 2 mo after insertion.

Thirteen (41.9%) of the 31 patients still had a normal papilla. In 11 out of 13 patients (84.6%), the papilla was accessible via a Roux-en-Y loop, and only in two patients (15.3%) was it directly accessible from the Billroth IIstomach anastomosis via the afferent loop (Table 1).

The papilla could be reached with conventional PE in two of these 13 (15.3%) cases, and ERCP could be successfully performed with this forward-viewing enteroscope.

In the remaining 11 patients (84.6%) with normal papilla and prior abdominal surgery, the papilla had to be searched by push-and-pull-enteroscopy. DBE-ERCP could only be performed after appropriate stabilization of the enteroscope in front of the papilla, partly by use of the balloons. The DBE-ERCP and treatment was successful in eight of the 11 cases (72.7%; Tables 2 and 3), while in three cases (27.2%), DBE-based endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) failed because of tangential position to the papilla, or because of a papillary tumor (re-operation in one patient, and PTCD in two).

In the eight successful DBE-ERCs, seven patients (87.5%) had papillotomies of 3-7 mm in length using a 6 Fr papillotome, whereby moderate pancreatitis and bleeding (14.2% for each) occurred as side effects. In total, 1.2 ± 0.4 endoprostheses were successfully placed via the forward-viewing enteroscope (four double pigtail 7 Fr prostheses, one double pigtail 8 Fr prosthesis, seven straight 7 Fr endoprosthesis, and one 7 Fr nasobiliary probe).

In addition, apart from bougienage with the 6 Fr papillotome, dilatations using a CRE dilation balloon (8-10 mm, Cook) and removal of 5 ± 11 concrements and sludge using baskets were carried out in cases of papillary or distal bile duct stenoses. For treatment of purulent cholangitis with concrements, a nasobiliary drainage for irrigation was also placed via the enteroscope and left for 3 d to perform endoscopic shockwave lithotripsy and clean the bile system.

Before intervention, laboratory testing determined that the patients presented with distinct cholestasis and bilirubin elevation (2.8 ± 3.1 mg/dL) and/or inflammatory symptoms (leukocytes 12 800 ± 10 200/μL, C-reactive protein 51 ± 37 mg/L). By performing DBE-ERCP with ostial incisions, papillotomies and/or implantation of biliary endoprostheses, a clear reduction of cholestasis and cholangitis parameters was obtained. Values for bilirubin (1.6 ± 2.0 mg/dL), leukocytes (6800 ± 4000/μL) and C-reactive protein (18 ± 21 mg/L) decreased significantly (P < 0.05).

Among 86 DBE-ERCPs, post-interventional cholangitis was not observed in any of the 31 patients treated by DBE-ERCP. However, after six of 86 examinations (6.9%) in 31 patients (19.3%), a lipase increase of more than twice the norm was seen on the day after DBE, whereas clinically significant post-ERCP pancreatitis (one mild and one moderate) was only seen after two examinations (2.3%) in two patients.

Post-interventional bleeding occurred in one of 86 examinations (1.1%) in 31 patients (3.2%) after papillotomy, which required emergency endoscopy, intensive care treatment, and blood transfusion.

Post-interventional stomach pain was experienced after six of 86 examinations (6.9%) in 31 patients (19.3%), whereas perforation occurred in two DBE-ERCPs (2.3%). One perforation developed immediately after ostial incision, while the second became evident 8 h later, with ileal perforation. Both perforations could be treated surgically, and no patient died due to complications of DBE-ERCP. No other fatalities following DBE-ERCP were recorded.

After two of 86 examinations (2.3%), two patients complained of abdominal pain that lasted > 24 h, and raised temperature developed on the day after the examination. Of note, one patient developed tonsillitis after DBE-ERCP (1.1%). No other serious side effects occurred.

The average duration of all DBE-ERCPs was 111 ± 54 min, and radiography took 9.0 ± 5.5 min with a dose of 2465 ± 1295 cGy/m2. The individually required examinations for each patient are listed in Table 3, which included the exact therapeutic procedures, time measurements, and premedication.

With regard to premedication, an average of 11.7 ± 2.8 mg midazolam and 124.9 ± 45 mg pethidine or 1156 ± 593 mg propofol was needed per patient undergoing DBE-ERCP. In addition, butylscopolamine was administered at an average dose of 44.8 ± 20 mg. During conscious sedation for DBE-ERCP, one patient each developed hypoxia induced by midazolam/pethidine or propofol, which led in each case to abortion of the examination.

The difficulties involved with endoscopic access to the bile ducts and the pancreas in patients with prior abdominal surgery before the introduction of DBE have been described previously[4-6,10-12,19-21]. The success rate of ERCP with a side-viewing endoscope, push-enteroscope or pediatric colonoscope in patients with previous surgery depends on a number of factors, e.g. type of previous surgery, length of afferent loop, post-surgical changes, or experience of the endoscopist. Usually, results tend to be very variable (e.g. success rate of Billroth II gastrojejunostomy up to 92%, Roux-en-Y reconstruction, 33%, and pancreaticojejunostomy, 8%) accompanied by high complication rates[4,6,19-21].

Access through conventional endoscopy was particularly difficult in our patients after several rounds of complex abdominal surgery (91.8% Roux-en-Y reconstruction, 8.1% gastrojejunostomy), and initially, access or treatment by gastroscope or duodenoscope was not possible. As recently outlined by several other investigators in small patients series[5-10,22-24], our stepwise approach with PE and DBE in 37 non-selected, consecutive post-surgical patients found that DBE-ERCP was clearly more efficient than PE. By the appropriate use of DBE in over two-thirds of cases, enteroanastomoses or papilla could be repeatedly reached, identified and satisfactorily visualized. The enteroscope could be stabilized also for bilio-pancreatic intervention. DBE-ERCP could be successfully conducted in 74.1% of the cases via the enteroscope, while PE reached biliary anastomoses or papilla in only 16.2% of the patients, which resulted in successful ERCP in only a minority of patients. Both results are in good agreement with recently published data for the approach by double- or single-balloon enteroscopy[5-10,22-26], as well as for earlier published data on postoperative or PE-based ERCP[4,11,19-21].

However, until a successful DBE-ERCP was achieved, several balloon-assisted enteroscopic cycles over an average length of 124 ± 47 cm of the small intestine, application of X-rays, and manual guidance of the enteroscope were necessary. In addition, a substantial effort in time, staffing and sedation had to be afforded. Compared with PE, the push-and-pull method by DBE proved to be markedly more effective, because pushing and stretching of small intestinal loops is reduced by regular retractions of the DBE cycle. The threading of the small intestine onto the DBE and the option to block the balloons at the enteroscope provides the enteroscope tip with a greater possibility of movement for identifying the biliary or pancreatic anastomoses or the papilla. In addition, sliding back of the enteroscope may be prevented by inflated balloons, which, compared with PE, explains the significantly higher effectiveness of interventions during DBE-ERCP.

Out of the 37 post-surgical patients with significant cholestasis and cholangitis, PE achieved a successful bile duct drainage in six (16.2%), whereas, before DBE was introduced, a far more invasive procedure, either PTCD or surgery, would have been carried out in the remaining 31 patients. PTCD carries a significantly higher morbidity and mortality risk compared to the endoscopic procedure[12,14-17,27,28], therefore, all consecutive patients with previous abdominal surgery were included in this prospective treatment protocol after DBE had been introduced in August 2005 at the University of Erlangen–Nuremberg. Of note, DBE facilitated successful ERCP with biliary interventional procedures leading to significant reduction of cholestasis or cholangitis in 23 of 31 patients (74.1%). Thus, PTCD could be avoided in those 23 post-surgical patients, because endoscopic biliary drainage was achieved.

In comparison to reported PTCD-induced complication and infection rates of up to 55%, and even mortality[12,14-17,27,28] only one case of post-papillotomy bleeding (3.2%), two of post-ERCP pancreatitis (6.4%) and two perforations (6.4%) occurred following DBE-ERCP, but no cholangitis or mortality has been recorded to date. Thus, this first prospective investigation from a university tertiary referral center confirms that DBE-ERCP has considerable potential to treat successfully benign (postoperative) or malignant biliary and papillary stenoses, bile duct concrements, and cholangitis, even in non-selected post-surgical patients[4-10], and it helps to reduce the number of percutaneous approaches. Only in eight of 31 patients (25.8%), in whom the biliary or pancreatic anastomoses or papilla could not be found via DBE, was PTCD finally necessary. Even when the biliodigestive anastomoses could not be found and/or DBE-ERCP failed because of tumor-changed papilla or choledocho- and hepaticojejunostomy, a change in treatment procedure could be attempted after construction of PTCD by using DBE. After introduction of the percutaneous tube into the small intestine, percutaneous drainage was successfully changed in four patients to internal drainage inserted via DBE (Table 3). This was achieved by application of a DBE-PTCD rendezvous procedure, which was performed for the very first time in Erlangen in 2006. Before the DBE era, a longer-lasting bougienage and Yamakawa prosthesis therapy or biliary metal stent implantation were often indicated after the initial PTCD puncture[12,14-17]. By the use of DBE-ERCP, however, the external drainage could be extracted from all four patients after 1 wk. Practically, methylene blue injected externally through the PTCD helps to identify the afferent loop and/or biliary anastomoses or papilla, so that these are more easily and quickly detected by the subsequent DBE.

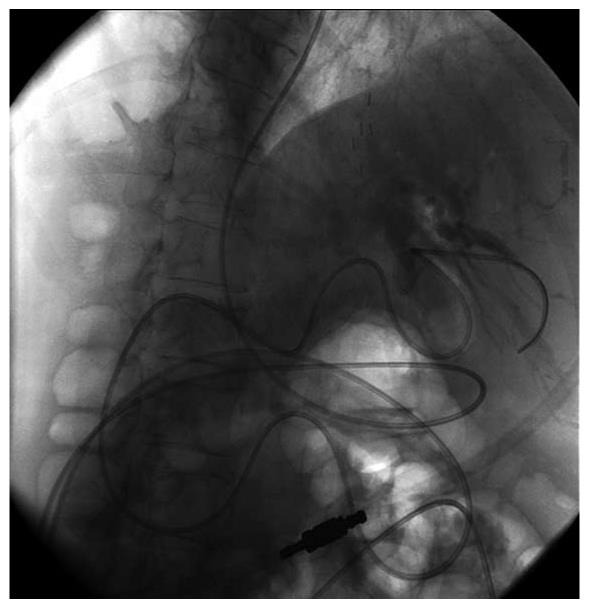

The key benefits of DBE-ERCP in the care of post-surgical patients with cholestasis/cholangitis and patients with installed percutaneous drainage are somewhat limited by the small caliber of bile duct prostheses that are applied via the enteroscope. According to the present state of technology, only an implantation of 5-8 Fr prostheses through an operating channel of 2.8 mm is possible. Consequently, several prostheses (1.5 ± 0.7) were implanted in our patients. In the case of strongly soiled bile ducts and concurrent cholangitis or sump syndrome, it is recommended first to apply a nasobiliary probe for irrigation of the bile ducts (Figure 4) to prevent rapid clogging of the small caliber bile duct prostheses.

The sequential coupling of two examinations (DBE and ERCP) explains the lengthy examination times, high doses of sedation, and applied fluoroscopy dosage. Considering the enormous benefit of DBE-ERCP with an approximately 74% successful biliary drainage and a significantly smaller complication rate than PTCD[11,12,14-17,27-29], the effort involved in such an examination seems justified.

In comparison to the more frequent cholestatic patients, only three of 37 patients also required radiography and interventions of the pancreatic duct after pancreatic resection. Overall, only a limited view could be gained as to which role DBE-ERCP might play in this area. In all three patients, the position of the pancreaticojejunostomy was only reached by DBE and was located deeper in the small intestine or considerably closer to the blind end of the afferent loop than was the choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomy. The technical conduction of the endoscopic retrograde pancreatography via DBE was undertaken in the same manner as described for ERCP. The ostium, however, was smaller, but in none of the cases stenotic. The main pathological changes of chronic pancreatitis were limited to the remaining pancreatic duct in the corpus area. During DBE-based pancreatography, a cystic lesion (pseudocyst) could be successfully drained via insertion of a 7 Fr double pigtail prosthesis for the first time, which led to a noticeable improvement of the patient, and regression of the pseudocyst within a week. Therefore, DBE offers also a novel option for pseudocyst drainage in postsurgical patients.

In conclusion, this prospective study from a single university tertiary referral center confirms the results from other investigators and shows that DBE-ERCP achieves a high rate of successful cholangiography and drainage in post-surgical patients[5-10,22-26,29], allows further treatment of pancreatic cystic lesions via pancreaticojejunostomy, and offers new possibilities in patients with PTCD as DBE-based rendezvous techniques are applicable.

Abdominal surgery involving the stomach, small bowel, pancreas, liver or biliary tract may change significantly the anatomy of these organs, with construction of small bowel anastomoses and small bowel limbs of differing length, angles or fixation. Thus, postoperative endoscopy with conventional endoscopes to reach the biliary tract or pancreas through small bowel limbs has often been described as unsatisfactory in postoperative disease.

Balloon-assisted endoscopy has been developed since 2004, with the introduction of a double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) system, followed later by single balloon endoscopy or balloon-guided enteroscopy techniques. All balloon-assisted endoscopy techniques have the potential to access more deeply into the small bowel than conventional endoscopes, and they allow one to examine the whole small bowel (4-7 m long). Thus, this study investigated the value of the DBE for examination of postoperative patients with diseases of the biliary tract or pancreas.

Before the era of balloon-assisted endoscopy, only 20%-30% of patients with diseases of the biliary tract or pancreas (e.g. tumor, stones, inflammation, stenosis) could be effectively managed by conventional endoscopy, whereas the other 70%-80% had to be treated by more invasive percutaneous puncture techniques, external tube insertion, drainage procedures, and more cost-intensive computed tomography (CT)-based therapies, or even re-operation. This paper describes, in a large number of consecutive patients, successful use of DBE to perform effective endoscopic treatment in a majority (74%) of post-surgical patients with bilio-pancreatic diseases.

DBE-based examination of the biliary tract or pancreas represents a further important endoscopic treatment modality for postoperative patients after complex abdominal resections. It allows successful application and interventions in post-surgical patients with bile duct stenosis, obstruction, stones or pancreatic diseases (chronic inflammation, tumor) in terms of performing incision of the bile duct ostium, or papillotomy, endoprosthesis insertion, or stone extraction.

DBE-based examination of the biliary tract and pancreas is achieved by forward-viewing optics in post-surgical patients, and requires examination of the small bowel by DBE, and includes endoscopic–radiological examination of the bile duct and/or pancreatic duct, with the aim of performing interventions in the case of bile duct, liver or pancreatic disease. This whole procedure is called DBE-based retrograde cholangiopancreaticiography and is indicated only when conventional endoscopy fails to reach the biliary tract or pancreas.

This study describes the utility of modern enteroscopy, especially DBE, in symptomatic patients with cholestasis and cholangitis after complex abdominal surgery. A high rate of enteroscopic access and successful biliary interventional procedures, with a new intervention, ostial incision at biliary anastomoses is presented, which resulted in a substantial reduction in more invasive procedures such as transhepatic percutaneous biliary interventions or CT-guided punctures.

Peer reviewer: Radha Krishna Yellapu, MD, DM, Dr., Department of Hepatology, Mount Sinai, 121 E 97 STREET, NY 10029, United States

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Iino S, Ido K, Sugano K. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216-220. |

| 2. | Kita H, Yamamoto H. New indications of double balloon endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:S57-S59. |

| 3. | May A, Nachbar L, Wardak A, Yamamoto H, Ell C. Double-balloon enteroscopy: preliminary experience in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding or chronic abdominal pain. Endoscopy. 2003;35:985-991. |

| 4. | Haber GB. Double balloon endoscopy for pancreatic andbiliary access in altered anatomy (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:S47-S50. |

| 5. | Chu YC, Su SJ, Yang CC, Yeh YH, Chen CH, Yueh SK. ERCP plus papillotomy by use of double-balloon enteroscopy after Billroth II gastrectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1234-1236. |

| 6. | Haruta H, Yamamoto H, Mizuta K, Kita Y, Uno T, Egami S, Hishikawa S, Sugano K, Kawarasaki H. A case of successful enteroscopic balloon dilation for late anastomotic stricture of choledochojejunostomy after living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1608-1610. |

| 7. | Chahal P, Baron TH, Topazian MD, Petersen BT, Levy MJ, Gostout CJ. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in post-Whipple patients. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1241-1245. |

| 8. | Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P. ERCP with the double balloon enteroscope in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1961-1967. |

| 9. | Pohl J, May A, Aschmoneit I, Ell C. Double-balloon endoscopy for retrograde cholangiography in patients with choledochojejunostomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction. Z Gastroenterol. 2009;47:215-219. |

| 10. | Aabakken L, Bretthauer M, Line PD. Double-balloon enteroscopy for endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in patients with a Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1068-1071. |

| 11. | Feitoza AB, Baron TH. Endoscopy and ERCP in the setting of previous upper GI tract surgery. Part II: postsurgical anatomy with alteration of the pancreaticobiliary tree. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:75-79. |

| 12. | Park JS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Seo DW, Lee SS, Han J, Min YI, Hwang S, Park KM, Lee YJ. Efficacy of endoscopic and percutaneous treatments for biliary complications after cadaveric and living donor liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:78-85. |

| 13. | Maiss J, Diebel H, Naegel A, Müller B, Hochberger J, Hahn EG, Raithel M. A novel model for training in ERCP with double-balloon enteroscopy after abdominal surgery. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1072-1075. |

| 14. | Yee AC, Ho CS. Complications of percutaneous biliary drainage: benign vs malignant diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:1207-1209. |

| 15. | Schumacher B, Othman T, Jansen M, Preiss C, Neuhaus H. Long-term follow-up of percutaneous transhepatic therapy (PTT) in patients with definite benign anastomotic strictures after hepaticojejunostomy. Endoscopy. 2001;33:409-415. |

| 16. | Ell C. Perkutane transhepatische Cholangiographie (PTC - PTCD). Gastro Update 2003. Schnetztor: Verlag, Konstanz 2003; 470. |

| 17. | Winick AB, Waybill PN, Venbrux AC. Complications of percutaneous transhepatic biliary interventions. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;4:200-206. |

| 18. | May A, Nachbar L, Schneider M, Ell C. Prospective comparison of push enteroscopy and push-and-pull enteroscopy in patients with suspected small-bowel bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2016-2024. |

| 19. | Faylona JM, Qadir A, Chan AC, Lau JY, Chung SC. Small-bowel perforations related to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy. Endoscopy. 1999;31:546-549. |

| 20. | Wright BE, Cass OW, Freeman ML. ERCP in patients with long-limb Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy and intact papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:225-232. |

| 21. | Hintze RE, Adler A, Veltzke W, Abou-Rebyeh H. Endoscopic access to the papilla of Vater for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with billroth II or Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. Endoscopy. 1997;29:69-73. |

| 22. | Spahn TW, Grosse-Thie W, Spies P, Mueller MK. Treatment of choledocholithiasis following Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy using double-balloon endoscopy. Digestion. 2007;75:20-21. |

| 23. | Emmett DS, Mallat DB. Double-balloon ERCP in patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y surgery: a case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1038-1041. |

| 24. | Chahal P, Baron TH, Poterucha JJ, Rosen CB. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in post-orthotopic liver transplant population with Roux-en-Y biliary reconstruction. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1168-1173. |

| 25. | Mönkemüller K, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P. Therapeutic ERCP with the double-balloon enteroscope in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:992-996. |

| 26. | Neumann H, Fry LC, Meyer F, Malfertheiner P, Monkemuller K. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using the single balloon enteroscope technique in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Digestion. 2009;80:52-57. |

| 27. | Cohan RH, Illescas FF, Saeed M, Perlmutt LM, Braun SD, Newman GE, Dunnick NR. Infectious complications of percutaneous biliary drainage. Invest Radiol. 1986;21:705-709. |