INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and the third most common cause of cancer mortality[1]. Underlying cirrhosis is present in 90% of cases. Its prognosis remains poor with lots of advanced forms, and there is no curative therapeutic approach.

Since 2007, sorafenib has been the standard treatment for first-line therapy of advanced or metastatic disease that is not eligible for intra-arterial chemo-embolization. It has been shown to significantly improve progression-free and overall survival[2]. However, sorafenib is not able to induce any objective response and tumor shrinkage that allows secondary surgery. Its role in neoadjuvant therapy has not been established either.

Although HCC has been documented as a chemoresistant tumor, some chemotherapeutic regimens, such as gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin, have shown some interesting efficacy results, with objective response rates around 20% and disease control rates > 50% in phase II trials[3-5]. Here, we report what is believed to be the first case of a patient with advanced HCC who received sorafenib together with gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin, which allowed secondary curative surgery.

CASE REPORT

A 61-year-old man, working as a radiologist, was admitted for a liver mass that was detected by ultrasonography that was performed for abdominal pain, in December 2009. He had a history of cholecystectomy and post-transfusional hepatitis C, which was treated effectively by interferon and ribavirin therapy in 1998. Clinically, the ECOG performance status was 0, the patient weighed 94 kg, his height was 188 cm, and he had no symptoms except for moderate abdominal pain that was controlled with class II analgesics. In January 2010, Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a 4.5-cm hypervascular hepatic tumor that occupied the sixth hepatic segment, without signs of underlying cirrhosis (Figure 1A). There were also two metastatic lymph nodes (MLNs): one celiac measuring 4 cm, and one measuring 3 cm located in the liver hilum (Figure 2A). Laboratory data showed normal blood cell and platelet counts, liver enzymes, bilirubin and albumin levels. α-fetoprotein (AFP) was markedly increased at 2572 ng/mL (upper limit of normal = 8). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy did not show gastroesophageal varices or other upper gastrointestinal tract abnormalities.

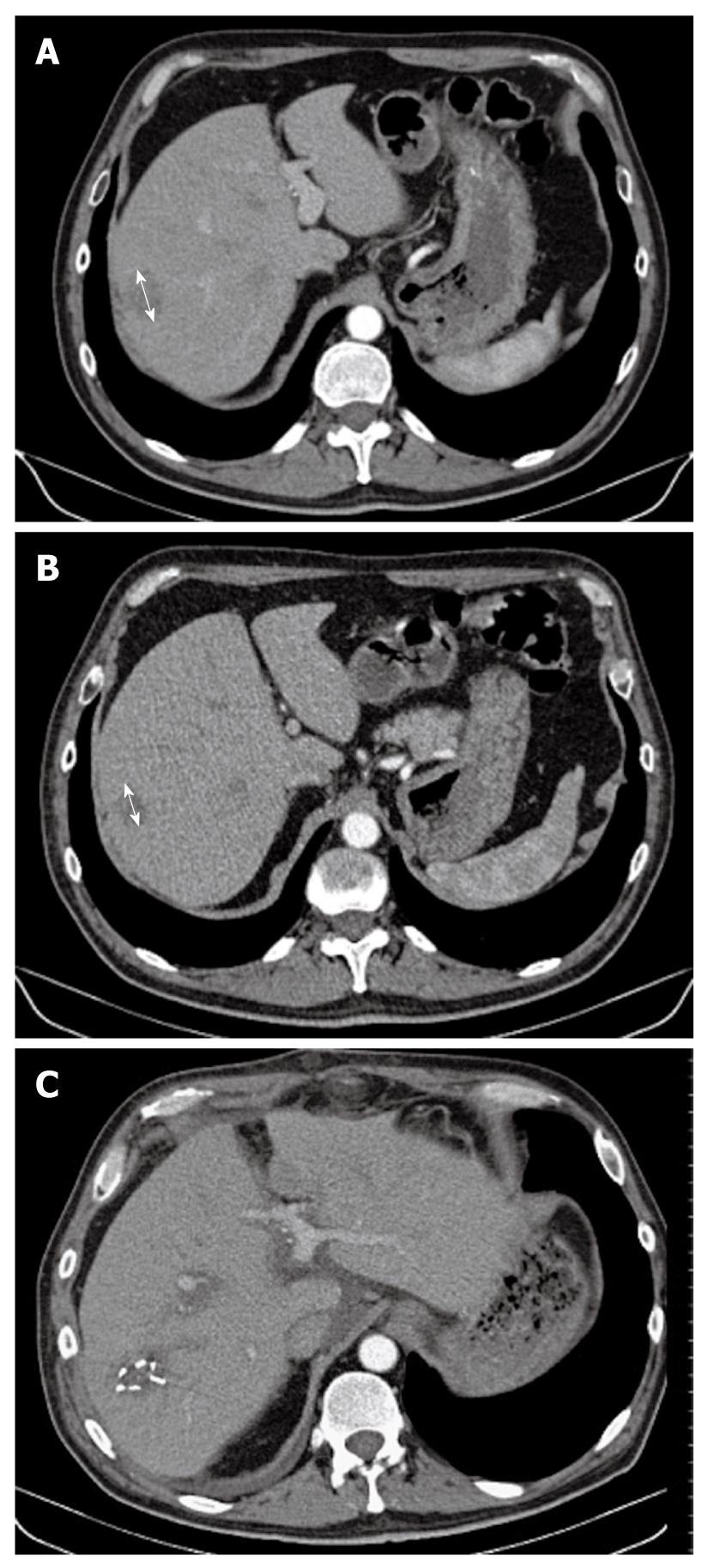

Figure 1 Computed tomography scan.

A: A 4.5-cm hypervascular hepatic tumor (arrow) that occupied the sixth hepatic segment, without signs of underlying cirrhosis; B: After eight cycles of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin combined with sorafenib, we observed tumor shrinkage of > 40% (arrow), as compared to baseline assessment; C: Secondary surgery was performed: hemostatic clips were still visible on this postoperative CT scan.

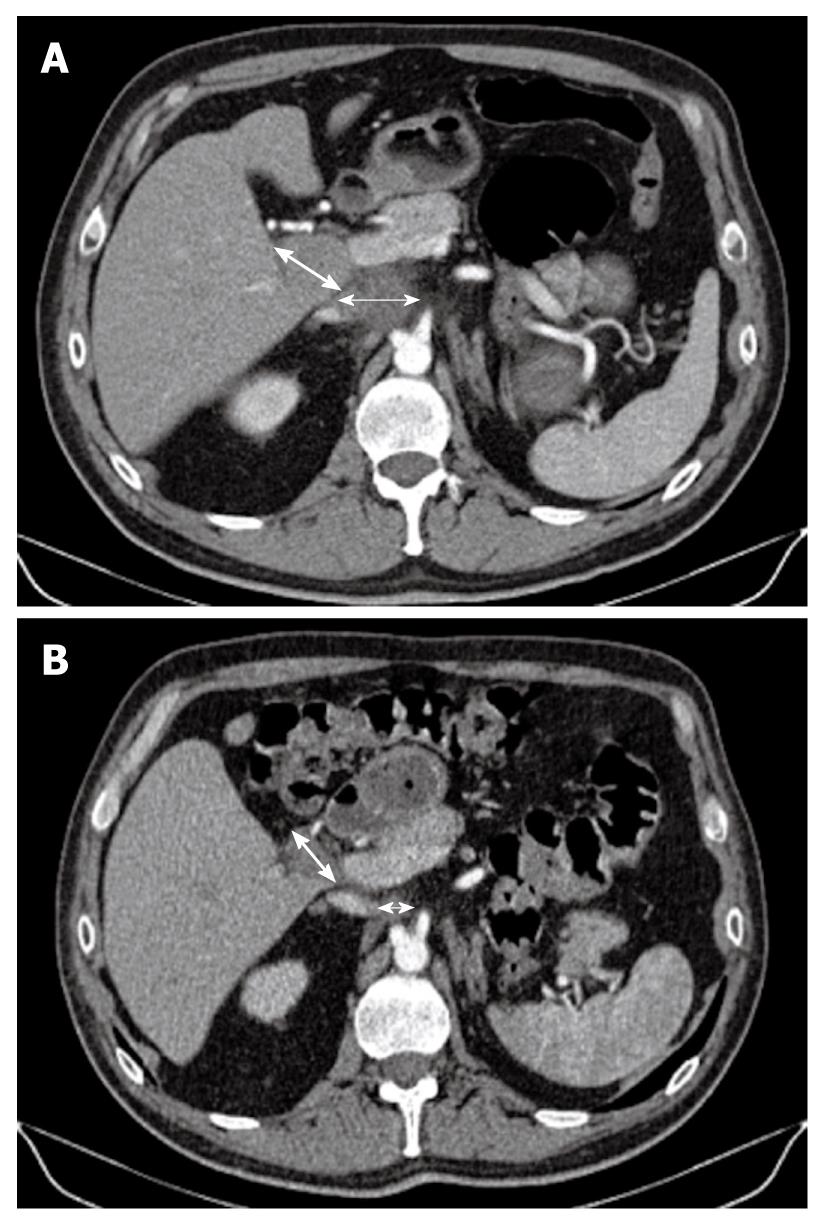

Figure 2 Computed tomography scan.

A: Initially, there were two metastatic lymph nodes (MLNs): one celiac (thin arrow) measuring 4 cm and one measuring 3 cm located in the liver hilum (thick arrow); B: Computed tomography scan taken after the end of the eight cycles of gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin combined with sorafenib, showed that the MLNs (thin arrow for celiac node and thick arrow for hilar node) decreased in size dramatically with a more necrotic aspect, which allowed secondary surgery followed by radiotherapy.

Fine needle echoendoscopic aspiration from celiac lymph nodes was performed and showed a typical trabecular liver carcinoma. Evaluation by a multidisciplinary team concluded that the primary tumor was theoretically resectable in this patient, who had an excellent performance status, without underlying cirrhosis, and who wished an aggressive therapeutic approach. However, because there were MLNs, initial surgery was rejected and intensive systemic therapy with sorafenib combined with gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin was initiated. He received four cycles of the GEMOX regimen (gemcitabine 1 g/m2 on day 1 and oxaliplatin 100 mg/m2 on day 2), as previously described[3]. This treatment was repeated every 2 wk and sorafenib was taken every day (400 mg twice daily). No grade 3/4 toxicities were observed. Grade 1 diarrhea, thrombopenia and neurotoxicity were reported, together with grade 2 asthenia after the fourth cycle. Efficacy assessment showed a decrease of AFP from 2572 to 97 ng/mL. CT scan showed tumor shrinkage of 25% in the liver (Figure 1B), and a slight decrease in MLN size, which were more necrotic (Figure 2B). A new multidisciplinary evaluation was performed and it was decided to continue the same therapeutic schedule for more cycles. Second efficacy evaluation showed normalization of AFP levels (2.7 ng/mL) and tumor volume reduction of around 40% (Figure 2A), as compared to baseline assessment.

Surgery was then decided upon, which consisted of removing the primary tumor, together with satellite adenopathies. The sites were marked by surgical clips (Figure 1C) to allow for postoperative radiotherapy (RT).

Pathological examination of the specimens showed a well-differentiated HCC that measured 2.5 cm, without underlying cirrhosis (METAVIR score A1F2). All resection margins were negative, and only one lymph node of five removed was metastatic, which was located in the liver hilum and measured 2 cm, with a necrotic center. There were no postoperative complications except for exacerbation of oxaliplatin-induced neurosensory toxicity, as previously described[6,7]. Global status of the patient improved and postoperative RT of MLNs was performed, by delivering 46 Gy over 5 wk, without any side effects. Complementary adjuvant chemotherapy, with combined sorafenib and gemcitabine for 3 wk in four, was started for 3 mo, and is currently ongoing. Oxaliplatin was not reintroduced because of persistent grade 2 neurosensory toxicity.

DISCUSSION

The role of chemotherapy in HCC patients is still a matter of debate. There is no clear evidence for efficacy of any tested schedule in the adjuvant (or neoadjuvant) setting, as reviewed by a recent Cochrane study[8]. However, many oncologists are using systemic chemotherapy for their HCC patients in a palliative setting. Doxorubicin, which was considered as potential standard chemotherapy 20 years ago, seems to be toxic and does not convincingly improve survival over that with supportive care[9]. Recent studies have suggested that oxaliplatin and gemcitabine could be interesting agents, alone or in combination, even if there has been no phase III trial to confirm their efficacy. The choice of gemcitabine-oxaliplatin combinations in this disease is based on: (1) synergy between the two drugs and their sequence dependency (gemcitabine followed by oxaliplatin is most active in preclinical models)[10]; (2) clinical activity of gemcitabine alone and of 5-fluorouracil/oxaliplatin combination in patients with HCC in phase II trials[11,12]; and (3) lack of renal and hepatic oxaliplatin toxicity in cirrhotic patients, unlike doxorubicin. The GEMOX combination has thus been evaluated in many phase II studies with promising results in term of response rate and survival[3-5,13]. Patients with complete response have been described by ourselves and others[14].

In the pivotal SHARP trial, response rate with sorafenib was particularly low (2.3%) and not significantly different from placebo[2]. To the best of our knowledge, only one patient receiving sorafenib and eligible for secondary surgery has been reported in the literature[15]. Sorafenib does not seem to be a candidate drug for tumor downstaging that allows secondary surgery. However, the antiangiogenic effect of sorafenib seems to modify HCC vascularization, by normalizing tumor vessels[16]. This vascular normalization has been described as potentially favoring chemotherapy efficacy through better delivery of the drugs to the tumor site[17]. Combination of sorafenib and GEMOX could thus lead to synergistic antitumor activity.

The toxicity of the GEMOX regimen has been well described over the past 10 years through 31 phase II and two phase III trials, mainly in pancreatic and biliary tract cancers. Grade 3 neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and neurotoxicity have been reported in 22%, 11% and 10%, respectively, and severe nausea has occurred in 16% of the cases[18]. These results are similar to those described in the phase II trials that have evaluated this combination in HCC patients with underlying cirrhosis. The elevated liver enzymes and anaphylactic reactions (due to gemcitabine and oxaliplatin, respectively) did not seem more frequent in this population.

In the SHARP trial, diarrhea (grade 2 in 50%, grade 3 in 10%), weight loss, fatigue, hand-foot skin reaction (grade 2 in 30%, grade 3 in 8%), and hypophosphatemia were the most frequent toxicities associated with sorafenib. To date, no trial has assessed GEMOX plus sorafenib combination therapy.

Adjuvant RT after resection of MLNs from HCC is not common. To the best of our knowledge, only two Asian cases have been described in the literature[19,20]. However, three retrospective studies have demonstrated its role in local control of MLNs from HCC that is not eligible for surgery, but is present in patients with good performance status. RT doses range from 40 to 60 Gy, and could prolong overall survival[21-23]. For example, in Zeng’s retrospective study on 125 patients, partial and complete responses were observed in 37.1% and 59.7% of patients, respectively. The median survival was 9.4 mo[23]. However, these results need to be confirmed. To avoid unnecessary toxicity, the RT dose chosen in the present case did not exceed 50 Gy[21].

In conclusion, this case is an example of successful multimodal aggressive treatment for advanced HCC, which combined for the first time, GEMOX and sorafenib followed by surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy. GEMOX + sorafenib combination therapy was well tolerated with only grade 1/2 toxicity that was easily manageable, and gave an objective response, together with a dramatic decrease in AFP levels. These promising results need to be confirmed and GEMOX/sorafenib combination therapy is currently being evaluated in an ongoing randomized phase II trial and compared to sorafenib alone.

Peer reviewer: Fernando J Corrales, Associate Professor of Biochemistry, Division of Hepatology and Gene Therapy, Proteomics Laboratory, CIMA, University of Navarra, Avd. Pío XII, 55, Pamplona, 31008, Spain

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM