Published online May 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i17.2206

Revised: January 11, 2011

Accepted: January 18, 2011

Published online: May 7, 2011

AIM: To determine if liver stiffness (LS) measurements by means of transient elastography (TE) correlate with the presence of significant esophageal varices (EV) and if they can predict the occurrence of variceal bleeding.

METHODS: We studied 1000 cases of liver cirrhosis divided into 2 groups: patients without EV or with grade 1 varices (647 cases) and patients with significant varices (grade 2 and 3 EV) (353 cases). We divided the group of 540 cases with EV into another 2 subgroups: without variceal hemorrhage (375 patients) and patients with a history of variceal bleeding (165 cases). We compared the LS values between the groups using the unpaired t-test and we established cut-off LS values for the presence of significant EV and for the risk of bleeding by using the ROC curve.

RESULTS: The mean LS values in the 647 patients without or with grade 1 EV was statistically significantly lower than in the 353 patients with significant EV (26.29 ± 0.60 kPa vs 45.21 ± 1.07 kPa, P < 0.0001). Using the ROC curve we established a cut-off value of 31 kPa for the presence of EV, with 83% sensitivity (95% CI: 79.73%-85.93%) and 62% specificity (95% CI: 57.15%-66.81%), with 76.2% positive predictive value (PPV) (95% CI: 72.72%-79.43%) and 71.3% negative predictive value (NPV) (95% CI: 66.37%-76.05%) (AUROC 0.7807, P < 0.0001). The mean LS values in the group with a history of variceal bleeding (165 patients) was statistically significantly higher than in the group with no bleeding history (375 patients): 51.92 ± 1.56 kPa vs 35.20 ± 0.91 kPa, P < 0.0001). For a cut-off value of 50.7 kPa, LS had 53.33% sensitivity (95% CI: 45.42%-61.13%) and 82.67% specificity (95% CI: 78.45%-86.36%), with 82.71% PPV (95% CI: 78.5%-86.4%) and 53.66% NPV (95% CI: 45.72%-61.47%) (AUROC 0.7300, P < 0.0001) for the prediction of esophageal bleeding.

CONCLUSION: LS measurement by means of TE is a reliable noninvasive method for the detection of EV and for the prediction of variceal bleeding.

- Citation: Sporea I, Raţiu I, Şirli R, Popescu A, Bota S. Value of transient elastography for the prediction of variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(17): 2206-2210

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i17/2206.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i17.2206

Transient elastography (TE) is a new promising noninvasive and rapid method for the diagnosis and quantification of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease. It was originally developed to detect solid malignancies in soft tissues such as breast cancer and prostate cancer[1]. Liver stiffness (LS) measurement using TE is reproducible and independent of the operator[2]. Some recent extensive studies have demonstrated that LS measurement with TE is a good alternative for liver biopsy. The amount of fibrosis can be quantified very easily and reliably and is feasible in more than 95% of the patients[3-5]. In cirrhotic patients, LS measurements range from 12.5 to 75.5 kPa. However, the clinical relevance of these values is unknown.

The risk of variceal hemorrhage is clearly related to the size of esophageal varices (EV). Therefore primary prevention of variceal bleeding applies in patients with previously diagnosed large EV (grade 2 or 3) detected by periodical upper digestive endoscopy [Baveno V and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) Consensuses][6,7]. A generalized program of periodical upper tract endoscopy in these patients might result in a heavy economic burden even for developed countries. Furthermore, repeated examinations, when not performed under profound sedation, are often poorly accepted by patients who may refuse further follow up.

TE may be used to predict the presence of portal hypertension. LS measurement may allow prediction of the presence of large EV in patients with cirrhosis and may help to select patients for endoscopic screening[8-11].

The purpose of this study was to determine if TE can be used to predict indirectly the presence of portal hypertension and the risk of variceal bleeding. At present the Baveno V and AASLD Consensuses recommend screening all cirrhotic patients for EV. If LS measurement could predict the presence of large EV in patients with cirrhosis, we could select these patients for endoscopic screening.

We studied 1000 consecutive patients with liver cirrhosis. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were excluded. In all patients, upper digestive endoscopy was performed by 10 experienced endoscopists (at least 300 upper digestive endoscopies performed). The time interval between endoscopy and TE evaluation was less than three months. EV were classified as: small (grade I) - small straight varices; medium (grade II) - enlarged tortuous varices occupying less than one third of the lumen; large (grade III) - large coil-shaped varices occupying more than one third of the lumen.

In accordance with EV diagnosed on endoscopy and the history of variceal bleeding we divided this batch into 2 groups: Group V0,1 - without EV and patients with grade 1 varices (647 cases); Group V2,3 - with significant portal hypertension (grade 2 and 3 EV) (353 cases).

We selected only those cases with EV and we divided them into 2 groups: Group no upper digestive bleeding (UDB) - without variceal hemorrhage (375 patients) and Group UDB - (165 cases) with variceal bleeding.

In all patients we performed LS measurement by TE using a FibroScan device (Echosens, Paris). Measurements were performed in the right lobe of the liver through the intercostal spaces, on patients lying in the dorsal decubitus position with the right arm in maximal abduction. The tip of the transducer probe was covered with coupling gel and placed on the skin, between the rib bones at the level of the right lobe of the liver. The operator, assisted by an ultrasonic time-motion image, located a liver portion of at least 6 cm thick, free of large vascular structures. Once the measurement area had been located, the operator pressed the probe button to start an acquisition. Measurement depth was between 25 mm and 65 mm below the skin surface. Measurements which did not had a correct vibration shape or a correct follow up of the vibration propagation were automatically rejected by the software. Ten successful measurements were performed on each patient. The success rate (SR) was calculated as the ratio of the number of successful measurements over the total number of acquisitions. The results are expressed in kilopascal (kPa). The median value of the successful measurements was kept as representative of LS. Only LS measurements obtained with at least 10 successful measurements, with a SR of at least 60% and an IQR < 30% (IQR, the interquartile range interval, is the difference between the 75th and the 25th percentile, essentially the range of middle 50% of the data) were considered reliable.

Both the endoscopist and FibroScan operator were blinded to the result of TE evaluation and endoscopic evaluation of EV, respectively.

For a statistical study of quantitative variables, the mean and standard variation were calculated. T-tests were performed to compare mean values of LS in various subgroups. The diagnostic performance of LS measurements was assessed by using receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves. ROC curves were thus built for the detection of various grades of EV and for predicting the risk of variceal bleeding. Optimal cut-off values for LS measurements were chosen to maximize the sum of sensitivity and specificity.

The statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office 2007) and GraphPad Prism 5 programs.

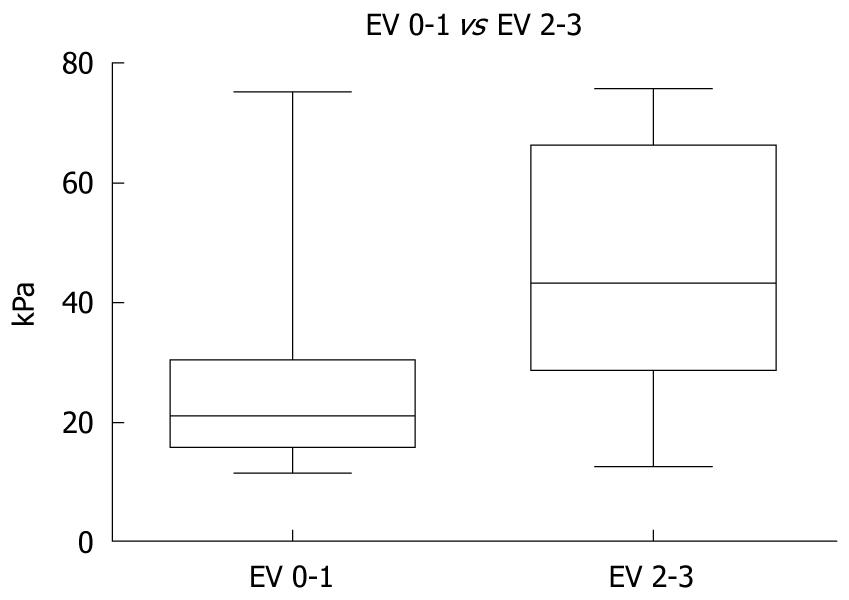

The mean LS values in the 647 patients without or with grade 1 EV were statistically significantly lower than in the 353 patients with significant EV (26.29 ± 0.60 kPa vs 45.21 ± 1.07 kPa, P < 0.0001) (Figure 1).

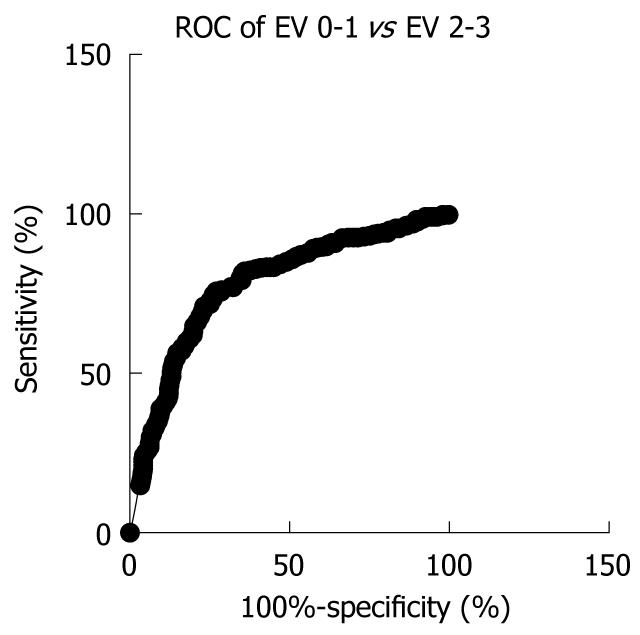

Using the ROC curve we established a cut-off value of 31 kPa for the presence of significant EV, with 83% sensitivity (95% CI: 79.73%-85.93%) and 62% specificity (95% CI: 57.15%-66.81%), with 76.2% positive predictive value (PPV) (95% CI: 72.72%-79.43%) and 71.3% negative predictive value (NPV) (95% CI: 66.37%-76.05%) (AUROC 0.7807, P < 0.0001) (Figure 2).

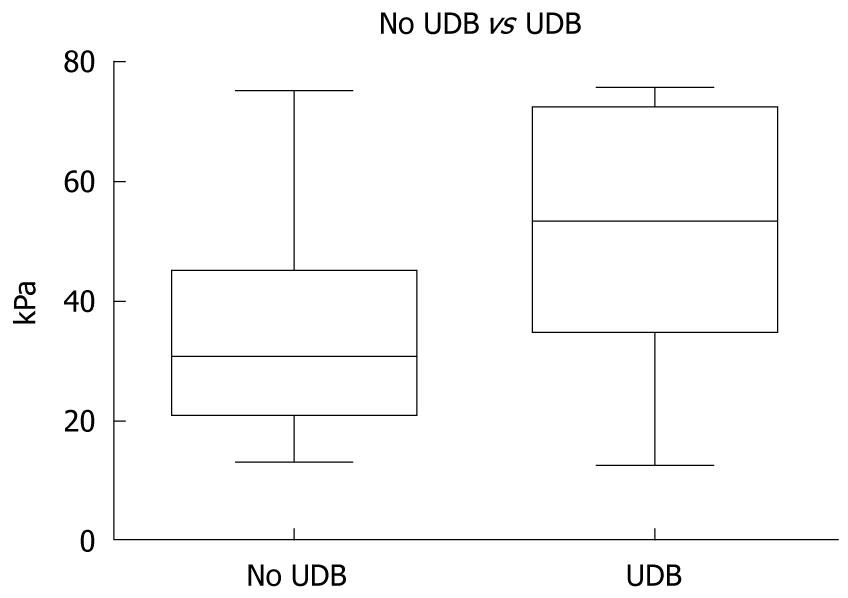

The mean LS values in the group with a history of variceal bleeding (165 patients) were statistically significantly higher than in the group with no bleeding history (375 patients): 51.92 ± 1.56 kPa vs 35.20 ± 0.91 kPa, P < 0.0001) (Figure 3).

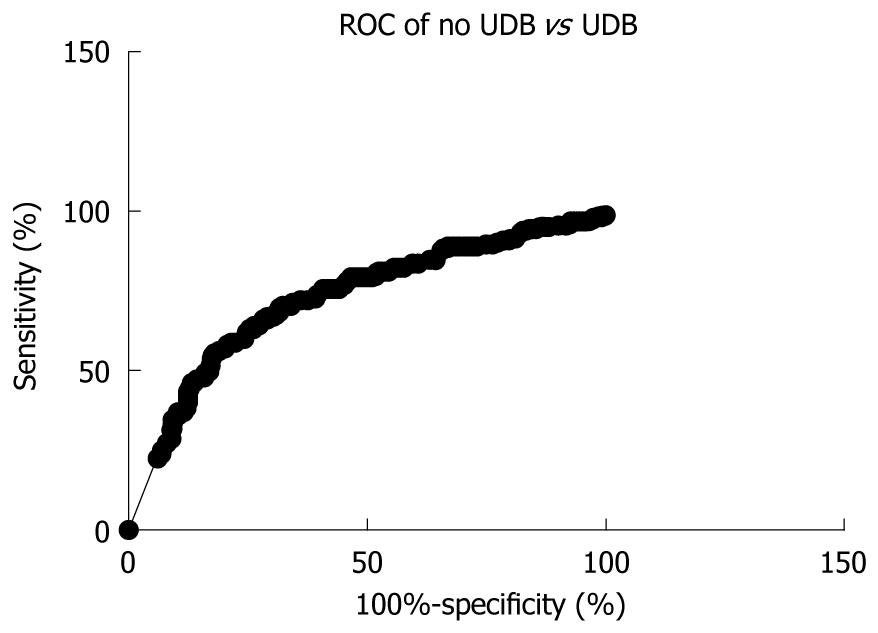

For a cut-off value of 50.7 kPa, LS had 53.33% sensitivity (95% CI: 45.42%-61.13%) and 82.67% specificity (95% CI: 78.45%-86.36%), with 82.71% PPV (95% CI: 78.5%-86.4%) and 53.66% NPV (95% CI: 45.72%-61.47%) (AUROC 0.7300, P < 0.0001) (Figure 4).

In previous studies, LS values < 19 kPa were highly predictive of the absence of significant EV (≥ grade 2), the cut off values for the presence of grade 2 and 3 EV ranging from 27.5 to 35 kPa, and the cut off value for esophageal bleeding being 62.7 kPa[12-14].

In other studies, LS measurement by TE was not accurate for the prediction of EV, with AUROC ranging from 0.76 to 0.84. Although sensitivity was good (71%-96%), specificity and PPV were low (60%-80% and 48%-54%, respectively) and overall accuracy was inferior as compared to simple tests like platelet count/spleen diameter ratio[11]. Another problem arising from these studies is the wide range of proposed cut offs, varying from 13.9 to 21.3 kPa for all varices, from 19 to 30 kPa for grade 2 varices and from 55 to 63 kPa for bleeding varices. The optimal cut offs therefore are still to be defined[15,16].

Foucher et al[13] (2006) assessed the accuracy of TE for the detection of large EV and the risk of variceal bleeding in patients with chronic liver disease. For the presence of EV grade 2 and 3, and esophageal bleeding, the cut offs were 27.5 and 62.7 kPa, respectively. The authors concluded that TE use for the follow-up and management of these patients could be of great interest and should be evaluated further.

Rudler et al[17] reported their data on consecutive patients admitted to the intensive care unit with variceal hemorrhage who underwent hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) measurement and TE. With an HVPG cut off > 20 mmHg (HVPG > 20 mmHg is an independent predictor of death in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding), 8 patients were enrolled, but 4 could not undergo elastography because of severe ascites. Correlation between LS and HVPG was poor. The authors concluded that TE is unlikely to be of utility in this patient population.

Klibansky et al[18] was more successful in describing a useful application of TE to predict clinical outcomes in cirrhosis. Clinical endpoints were defined as the development of ascites or encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, development of hepatocellular carcinoma, or liver transplantation. Multivariate analysis indicated that the only independent predictors of outcome were Child-Pugh score and LS.

In 2009, Castéra et al[19] showed that TE could be a valuable tool for the diagnosis of cirrhosis but cannot replace endoscopy for variceal screening.

Another study assessed the correlation between LS with FibroScan and HVPG in diagnosing significant portal hypertension in 150 patients who underwent a liver biopsy and hemodynamic measurements. In patients with significant portal hypertension (HVPG > 10 mmHg), AUROC for FibroScan was 0.945. The cut off value of 21 kPa accurately predicted significant portal hypertension in 92% of patients for whom measurements were successful[20].

Due to the controversial results of all the studies described above we wanted to evaluate the value of TE for the prediction of EV and for the risk of bleeding in our patients.

The results of our study showed that TE is a useful technique for evaluating the presence of EV and hemorrhage prediction in cirrhotic patients. For a cut off value of 31 kPa, negative and PPVs were 76.2% and 71.3%, respectively. For > 31 kPa criterion, the cut off value was chosen to maximize the sum of sensitivity and specificity, whereas for > 40 kPa criterion we chose a cut off value to have a PPV of more than 85% with 77.8% sensitivity (95% CI: 74.57%-80.79%), 68.3% specificity (95% CI: 62.55%-73.68%), 86% PPV (95% CI: 83.18%-88.66%) and 55% NPV (95% CI: 49.60%-60.23%). For a cut-off value of 17.1 kPa, chosen to have a NPV close to 90%, we found the NPV to be 89.3%, with 43.2% PPV, 92.6% sensitivity and 33.5% specificity.

In clinical practice, such results could be of major relevance for the follow up of patients with cirrhosis. Cirrhosis places the patient at risk of clinical complications, such as portal hypertension, and variceal rupture is the second cause of death in cirrhosis, justifying early screening for EV. The usual means of diagnosing EV is upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. However, endoscopy can be considered invasive due to the technique and level of discomfort and the last recent consensus did not recommend endoscopic screening for the evaluation of bleeding risk in patients with grade 2 or 3 EV[6,7]. Non-invasive methods for diagnosis need to be developed.

According to our data, in patients with TE values > 40 kPa at least 8/10 cases will have significant portal hypertension. Therefore it is reasonable to recommend prophylactic β-blocker therapy without endoscopy. On the other hand, in patients with TE values < 40 kPa, 5/10 cases will have significant EV (NPV 54.9%), thus we recommend endoscopic evaluation. Below the cut-off value of 17.1 kPa we do not recommend endoscopic evaluation, since the chance of those patients having significant EV is only 1 in 10 (NPV 89.3%).

In our study we established an LS cut off value of 50.7 kPa for the risk of bleeding. A cut off value higher than 64 kPa correlates with a PPV > 90%, which means that those patients have a very high risk of bleeding despite primary prophylaxis with propranolol, with 77.75% sensitivity (95% CI: 73.64%-81.50%), 72.94% specificity (95% CI: 62.21%-82%), 93.88% PPV (95% CI: 90.96%-96.08%), 38.04% NPV (95% CI: 30.56%-45.96%). This data shows that 9 from 10 cases with TE values above 64 kPa will have variceal bleeding and we recommend prophylactic ligation in patients with LS values of more than 64 kPa.

In conclusion, LS measurement by means of TE is accurate for assessing the presence of large EV and the risk of variceal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients.

The risk of variceal hemorrhage is related to the size of esophageal varices (EV). Therefore primary prevention of variceal bleeding applies in patients with previously diagnosed large EV (grade 2 or 3) detected by periodical upper digestive endoscopy. A generalized program of periodical upper tract endoscopy in these patients might result in a heavy economic burden even for developed countries. Furthermore, repeated examinations when not performed under profound sedation are often poorly accepted by patients who may refuse further follow up. Transient elastography (TE) may be used to predict the presence of portal hypertension. Liver stiffness (LS) measurement by means of TE may allow prediction of the presence of large EV in patients with cirrhosis and may help select patients for endoscopic screening

TE may be used to predict the presence of portal hypertension. LS measurement may allow prediction of the presence of large EV in patients with cirrhosis and may help to select patients for endoscopic screening. The purpose of this study was to determine if TE can be used to predict indirectly the presence of portal hypertension and the risk of variceal bleeding. Currently, the Baveno V and AASLD Consensuses recommend screening all cirrhotic patients for EV. If LS measurement could predict the presence of large EV in patients with cirrhosis, we could select these patients for endoscopic screening.

The study showed that, in patients with TE values > 40 kPa at least 8/10 cases will have significant portal hypertension. Therefore it is reasonable to recommend prophylactic β-blocker therapy without endoscopy. In patients with TE values < 40 kPa, 5/10 cases will have significant EV [negative predictive value (NPV) 54.9%], thus endoscopic evaluation is mandatory. Below the cut-off value of 17.1 kPa endoscopic evaluation is not recommended, since the chance of those patients having significant EV is only 1 in 10 (NPV 89.3%). The research team established a LS cut off value of 50.7 kPa for the risk of bleeding. A cut off value higher than 64 kPa correlates with a positive predictive value > 90%, which means that those patients have a very high risk of bleeding despite primary prophylaxis with propranolol. The data shows that 9 from 10 cases with TE values above 64 kPa will have variceal bleeding and they recommend prophylactic ligation in patients with LS values of more than 64 kPa.

The authors recommend prophylactic β-blocker therapy without endoscopy in all patients with LS measurements > 40 kPa. In patients with LS measurements between 17.1 kPa and 40 kPa, considered to be “the grey zone”, we recommend endoscopic evaluation of EV. Below the cut-off value of 17.1 kPa, endoscopic evaluation is not recommended since the chance of those patients to have significant EV is only 1 in 10 (NPV 89.3%). In patients with LS measurements higher than 64 kPa we recommend prophylactic band ligation of EV.

TE is a new promising noninvasive and rapid method for the diagnosis and quantification of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease. Some recent extensive studies have demonstrated that LS measurement by means of TE is a good alternative for liver biopsy. In cirrhotic patients, LS measurements range from 12.5 to 75.5 kPa.

This is a nice study on the important topic of the non invasive diagnosis of large EV. Its strengths are in its size and what appears to be reliable data from TE.

Peer reviewer: Ned Snyder, MD, FACP, AGAF, Professor of Medicine, Chief of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, The University of Texas Medical Branch, 301 University Blvd., Galveston, TX 77555-0764, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Sandrin L, Tanter M, Gennisson JL, Catheline S, Fink M. Shear elasticity probe for soft tissues with 1-D transient elastography. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2002;49:436-446. |

| 2. | Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM, Yon S, Fournier C, Mal F, Christidis C, Ziol M, Poulet B, Kazemi F. Transient elastography: a new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1705-1713. |

| 3. | Castéra L, Vergniol J, Foucher J, Le Bail B, Chanteloup E, Haaser M, Darriet M, Couzigou P, De Lédinghen V. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:343-350. |

| 4. | Friedrich-Rust M, Ong MF, Herrmann E, Dries V, Samaras P, Zeuzem S, Sarrazin C. Real-time elastography for noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis in chronic viral hepatitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:758-764. |

| 5. | Foucher J, Castéra L, Bernard PH, Adhoute X, Laharie D, Bertet J, Couzigou P, de Lédinghen V. Prevalence and factors associated with failure of liver stiffness measurement using FibroScan in a prospective study of 2114 examinations. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:411-412. |

| 6. | de Franchis R. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762-768. |

| 7. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938. |

| 8. | Del Poggio P, Colombo S. Is transient elastography a useful tool for screening liver disease? World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1409-1414. |

| 9. | Pritchett S, Afdhal N. The Optimal Cutoff For Predicting Large Esophageal Varices Using Transient Elastography Is Disease Specific. CDDW and the 5th Annual CASL Winter Meeting;. 2009;Feb 27-Mar 2; Banff, Alberta Available from: http://meds.queensu.ca/gidru/CDDW%20posters%202009.pdf. |

| 10. | Vizzutti F, Arena U, Romanelli RG, Rega L, Foschi M, Colagrande S, Petrarca A, Moscarella S, Belli G, Zignego AL. Liver stiffness measurement predicts severe portal hypertension in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45:1290-1297. |

| 11. | Lim JK, Groszmann RJ. Transient elastography for diagnosis of portal hypertension in liver cirrhosis: is there still a role for hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement? Hepatology. 2007;45:1087-1090. |

| 12. | Kazemi F, Kettaneh A, N'kontchou G, Pinto E, Ganne-Carrie N, Trinchet JC, Beaugrand M. Liver stiffness measurement selects patients with cirrhosis at risk of bearing large oesophageal varices. J Hepatol. 2006;45:230-235. |

| 13. | Foucher J, Chanteloup E, Vergniol J, Castéra L, Le Bail B, Adhoute X, Bertet J, Couzigou P, de Lédinghen V. Diagnosis of cirrhosis by transient elastography (FibroScan): a prospective study. Gut. 2006;55:403-408. |

| 14. | Khokhar A, Farnan R, MacFarlane C, Bacon B, McHutchison J, Afdhal N. Liver stiffness and biomarkers: correlation with extent of fibrosis, portal hypertension and hepatic synthetic function. Hepatology. 2005;42 Suppl 1: 433A. |

| 15. | Giannini E, Botta F, Borro P, Risso D, Romagnoli P, Fasoli A, Mele MR, Testa E, Mansi C, Savarino V. Platelet count/spleen diameter ratio: proposal and validation of a non-invasive parameter to predict the presence of oesophageal varices in patients with liver cirrhosis. Gut. 2003;52:1200-1205. |

| 16. | Castera L, Bernard PH, Le Bail B, Foucher J, Merrouche W, Couzigou P, de Ledinghen V. What is the best non invasive method for early prediction of cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C? Prospective comparison between Fibroscan and serum markers (Lok index, APRI, AST/ALT ratio, platelet count and Fibrotest). Hepatology. 2007;46 Suppl 1:581A. |

| 17. | Rudler M, Cluzel P, Massard J, Varaut A, Lebray P, Auguste M, Poynard T, Thabut D. Transient elastography (FibroScan) and hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement in patients with cirrhosis and gastrointestinal haemorrhage related to portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2008;48:324A. |

| 18. | Klibansky D, Blanco PG, Kelly E, Brown A, Afdhal NH. Liver stiffness predicts clinical outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2008;48:1057A. |

| 19. | Castéra L, Le Bail B, Roudot-Thoraval F, Bernard PH, Foucher J, Merrouche W, Couzigou P, de Lédinghen V. Early detection in routine clinical practice of cirrhosis and oesophageal varices in chronic hepatitis C: comparison of transient elastography (FibroScan) with standard laboratory tests and non-invasive scores. J Hepatol. 2009;50:59-68. |

| 20. | Bureau C, Metivier S, Peron JM, Selves J, Robic MA, Gourraud PA, Rouquet O, Dupuis E, Alric L, Vinel JP. Transient elastography accurately predicts presence of significant portal hypertension in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1261-1268. |