Published online Apr 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i15.1976

Revised: October 5, 2010

Accepted: October 12, 2010

Published online: April 21, 2011

AIM: To investigate clinical characteristics associated with the presence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms in hemodialysis (HD) patients.

METHODS: This was a cross-sectional study. A questionnaire based on the Bowel Disease Questionnaire that records gastrointestinal symptoms was given to 294 patients in 4 dialysis centers. A total of 196 (67%) subjects returned the survey. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to identify factors significantly associated with IBS symptoms.

RESULTS: Symptoms compatible with IBS were present in 27 (13.8%) subjects and independently associated with low post-dialysis serum potassium [OR = 0.258, 95% CI (0.075-0.891), P = 0.032], paracetamol use [OR = 3.159, 95% CI (1.214-8.220), P = 0.018], and Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL) cognitive function score [OR = 0.977, 95% CI (0.956-0.999), P = 0.042]. Univariate regressions were also performed and the reported significance is for multivariate analysis. No association was detected for age, gender, depressed mood, smoking (present or past), body mass index, albumin level, Kt/V, sodium pre- or post-dialysis level, change in potassium level during HD, proton pump inhibitor or H2 blocker use, aspirin use, residual diuresis, hepatitis B or C infection, diabetes mellitus, marital status and education level.

CONCLUSION: This study examined potential risk factors for symptoms compatible with IBS in HD patients and identified an association with paracetamol use, post-dialysis potassium level and KDQOL-cognitive function score.

- Citation: Fiderkiewicz B, Rydzewska-Rosołowska A, Myśliwiec M, Birecka M, Kaczanowska B, Rydzewska G, Rydzewski A. Factors associated with irritable bowel syndrome symptoms in hemodialysis patients. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(15): 1976-1981

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i15/1976.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i15.1976

Chronic gastrointestinal symptoms are common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The prevalence rate is reportedly as high as 70%[1-4], and there is an association with impaired psychological well-being[5]. Among these gastrointestinal symptoms, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is also more frequent than in the general population, and is present in 11%-44% of hemodialysis (HD) patients[2-4]. Although the pathophysiology of IBS is uncertain, altered gut reactivity (motility, secretion), visceral hypersensitivity and dysregulation of the brain-gut axis are believed to play an important role[6]. The risk factors associated with IBS in HD patients are not known. The aim of this study was to determine the possible relationship between IBS symptoms in HD patients and their clinical characteristics.

This was a cross-sectional study. All patients in 4 HD centers (2 state financed and 2 privately owned) were asked to complete a questionnaire. The questionnaires were given to patients during a planned hemodialysis procedure. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

All of the subjects were Caucasian. They were dialyzed 3 times a week for 180 to 300 min using either polysulfone or cellulose acetate dialyzers and bicarbonate dialysis fluid containing 2 mEq/L of potassium in 3 centers and 2 or 3 mEq/L (adjusted on the basis of the knowledge of prevailing pre-dialysis serum potassium levels in a given individual) in 1center.

Causes of ESRD were as follows: glomerulonephritis, n = 60 (30.6%); diabetic nephropathy, n = 32 (16.3%); amyloidosis, n = 11 (5.6%); polycystic kidneys, n = 22 (11.2%); hypertension/atherosclerosis, n = 16 (8.2%); tubulo-interstitial disease, n = 39 (19.9%); unknown/uncertain, n = 15 (7.7%); nephrectomy, n = 1 (0.5%).

A questionnaire based on the Bowel Disease Questionnaire was used[7]. It was translated to the Polish language by 2 of the authors (BF, AR). Translations were compared and discrepancies reconciled. The resulting translation was then tested in 20 randomly selected dialysis patients, and as a result some of the expressions in the translation were altered to make them easier to understand. The questionnaire was then checked by a person who was not involved in translation (ARR), and finally evaluated by a certified gastroenterologist (GR).

IBS was defined using Manning criteria[8] as described by Talley et al[9], as an ache or pain that occurred more than 6 times per year which was either often made better by a bowel movement or often associated with more frequent or looser bowel movements when the pain began. In addition, 2 or more of the following symptoms had to be present: fewer than 3 bowel movements per week or more than 3 bowel movements per day; loose, watery stools or hard stools; straining to have bowel movements; feelings of incomplete rectal evacuation; urgency; mucus; or bloating with distention.

Additionally, we included questions taken from the validated Polish translation of Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL) questionnaire, related to depressed mood and cognitive function[10]. Depressed mood was measured by the following KDQOL items: How much of the time during the last 30 d have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up? and How much of the time during the last 30 d have you felt downhearted and blue? The six possible responses to these questions were (1) none of the time; (2) a little of the time; (3) some of the time; (4) a good bit of the time; (5) most of the time; and (6) all of the time. Patients were classified as reporting depressed mood when they indicated that they had felt down in the dumps or felt downhearted and blue a good bit of the time or more often[11].

Cognitive function was measured by the KDQOL-CF score. Patients had to answer the following questions: During the past 4 wk, did you react slowly to things that were said or done? Did you have difficulty concentrating or thinking? Did you become confused? Responses on a six-point scale were weighted and transformed to a score ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better self-assessed cognitive function[12].

Relevant laboratory and clinical data were extracted from medical records. Data corresponding closest to the date of the HD session during which the questionnaire was distributed, were used. We allowed for a time span of 14 d before and after HD.

Results are expressed as means ± SD or frequency. Variables were tested for normality of distribution using the Wilk-Shapiro test. The Fisher’s exact test and χ2 test were used for comparing categorical variables, as appropriate.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression was used to identify patient characteristics associated with IBS compatible symptoms. Risk factors considered in this analysis included age, sex, education level, marital status, presence of diabetes mellitus, procedure, hemoglobin level, pre- and post-HD potassium level, change in potassium level during HD, use of paracetamol in the last year, KDQOL-CF score, depressed mood, smoking (present or past), body mass index (BMI), albumin level, Kt/V, sodium pre- and post-dialysis level, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or H2 blocker use, aspirin and paracetamol use, residual diuresis, hepatitis B or C infection. Variables were included in the multivariable logistic model if P < 0.10 in the univariate analysis. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The software, used for statistical computations was Stata 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

A total of 294 HD patients were asked to complete the questionnaire, of which 196 were returned giving a 67% response rate. All the responders completed the questionnaires by themselves. Their clinical characteristics are given in Table 1.

| Group | IBS symptoms | All | P value | |

| (+) | (-) | |||

| n | 27 | 169 | 196 | |

| Gender (M/F) | 13/14 | 105/64 | 118 / 78 | 0.168 |

| Age (yr) | 68.1 ± 11.5 | 63.2 ± 13.4 | 63.9 ± 13.2 | 0.073 |

| Dialysis duration (min) | 40.1 ± 36.9 | 38.6 ± 45.8 | 38.8 ± 44.6 | 0.874 |

| BMI (kg//m2) | 25.0 ± 3.7 | 24.9 ± 4.9 | 24.9 ± 4.7 | 0.897 |

| Residual diuresis (mL/24 h) | 301 ± 559 | 401 ± 592 | 388 ± 42 | 0.411 |

| Kt/V | 1.26 ± 0.31 | 1.21 ± 0.27 | 1.22 ± 0.28 | 0.355 |

| Hepatitis C or B infection (n) | 7 (25.9%) | 31 (18.3%) | 38 (19.4%) | 0.430 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.4 ± 1.4 | 10.7 ± 1.5 | 10.8 ± 1.5 | 0.026a |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.72 ± 0.40 | 3.71 ± 0.44 | 3.71 ± 0.44 | 0.857 |

| Smoking (n) | 7 (25.9%) | 23 (13.6%) | 30 (15,3%) | 0.144 |

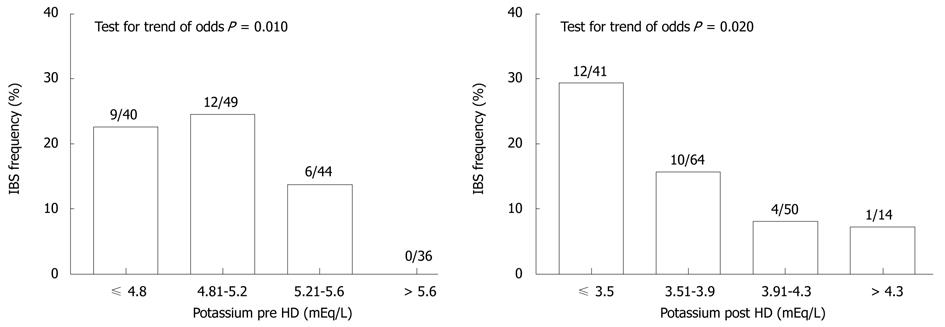

Symptoms compatible with IBS were present in 27 (13.8%) subjects. They were more common in women (18.0%) than in men (11.0%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.168). Symptoms of IBS were more frequent in patients with a post-hemodialysis potassium level ≤ 3.5 mEq/L than in subjects with potassium > 3.5 mEq/L. Also pre-dialysis potassium level was related to the frequency of IBS symptoms (Figure 1).

In univariate logistic regression, pre-dialysis serum potassium [OR = 0.462, 95% CI (0.222-0.965), P = 0.040], post-dialysis serum potassium [OR = 0.237, 95% CI (0.084-0.666), P = 0.006], hemoglobin level [OR = 1.403, 95% CI (1.038-1.897), P = 0.028], use of paracetamol in the last year [OR = 3.541, 95% CI (1.499-8.364), P = 0.004], and KDQOL-CF score [OR = 0.972, 95% CI (0.954-0.991), P = 0.004] were associated with IBS symptoms. Age (P = 0.076), gender (P = 0.172), depressed mood (P = 0.118), smoking (present or past) (P = 0.105), BMI (P = 0.896), albumin level (P = 0.856), Kt/V (P = 0.353), sodium pre- (P = 0.961) or post-dialysis level (P = 0.176), change in potassium level during HD (P = 0.556), PPI or H2 blocker use (P = 0.857), aspirin use (P = 0.172), residual diuresis (P = 0.411), hepatitis B or C infection (P = 0.358), diabetes mellitus (P = 0.822), marital status (P = 0.941) and education level (P = 0.377) were not associated with IBS symptoms.

When the risk factors for symptoms of IBS were assessed by multiple logistic regression analysis, independent predictors of IBS symptoms included: paracetamol use, post-dialysis serum potassium and KDQOL-CF score (Table 2).

| Variable | b coefficient (SE) | P value | OR (95% CI) |

| Potassium level pre-HD | -0.325 ± 0.437 | 0.457 | 0.723 (0.307-1.703) |

| Potassium level post-HD | -1.356 ± 0.633 | 0.032a | 0.258 (0.075-0.891) |

| Paracetamol use | 1.150 ± 0.488 | 0.018a | 3.159 (1.214-8.220) |

| Cognitive function | -0.023 ± 0.011 | 0.042a | 0.977 (0.956-0.999) |

| Hemoglobin | 0.327 ± 0.168 | 0.052 | 1.387 (0.998-1.928) |

| Age | 0.026 ± 0.021 | 0.213 | 1.027 (0.985-1.070) |

The frequency of symptoms compatible with IBS in our study is somewhat higher than that reported (11%) among 105 Austrian HD patients[3] using similar criteria, and lower than that among 148 English HD patients (21%) using Rome II criteria[2]. In the latter study, IBS was significantly more common in HD subjects than in both hospital outpatients and community controls[2]. In a study from Turkey, the prevalence of IBS, using Rome II criteria, was 44% among 93 HD patients, significantly more common than in healthy volunteers (21%)[4].

The overall IBS prevalence in Europe is 11.5%[13]. It varies, however, widely among countries, being highest in the UK and Italy[13], depending to a large extent on the diagnostic criteria used[14]. There is even more variability between continents[15]. Unfortunately, there is no data on IBS prevalence in the general population in Poland.

As there is no biologic marker of the disease, the diagnosis of IBS relies heavily on symptom-based criteria. The most widely used is a consensus definition called the Rome criteria[16,17], where IBS is defined chiefly by abdominal pain associated with defecation or a change in bowel habit and with features of disordered defecation. Some researchers have suggested that these criteria overemphasize abdominal pain and fail to emphasize postprandial urgency, abdominal pain, and/or diarrhea[18,19]. We thought that for the HD population, with frequent comorbidities, the use of supportive symptoms that are not part of the Rome criteria would be more appropriate. The Kruis scoring system[20], which in addition to self-reported symptoms includes: erythrocyte sedimentation rate, leukocytosis and anemia could not be used in HD patients for obvious reasons.

Fulfillment of IBS criteria is not unequivocally diagnostic of IBS, however, to make a positive diagnosis of IBS the use of diagnostic criteria is the recommended method, rather than exhaustive investigations to exclude an underlying organic cause[21]. Surprisingly, however, very few studies have examined the utility of the various diagnostic criteria in differentiating IBS from organic disease. The authors of a recent systematic review were able to find only 4 studies that reported on the accuracy of the Manning criteria, 1 study that reported on the Rome I criteria, and no studies on the Rome II or Rome III criteria[21].

In clinic-based studies, IBS has been associated with female gender, psychological distress, physical and sexual abuse, food allergies, enteric infections, and previous abdominal surgeries[22]. In a community-based study Locke et al[23]found associations with somatic symptoms, analgesic use, and food allergies and sensitivities[23].

The association between acetaminophen use and IBS has been previously reported, and is difficult to explain[23]. A possibility exists that most people take paracetamol for their IBS. It is interesting that there was no association between aspirin use and IBS symptoms, similar to Locke et al[23] when the use of these drugs was reported independently. Additionally, in this country aspirin is most frequently used for cardiovascular prophylaxis.

Cognitive deficits often accompany chronic illnesses, although the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood and may differ between diseases. Cognitive impairment is common in HD patients[24]. Risk factors include: age, race, stroke, diabetes, low education status, anemia, measures of malnutrition and an equilibrated Kt/V ≥ 1.2[25,26]. Also, IBS in the general population is associated with cognitive impairment[27,28]. An observed association between IBS symptoms and KDQOL-CF score might suggest that IBS worsens cognitive deficits in HD patients. We used the KDQOL-CF self reported score for the assessment of cognitive function. Although the KDQOL-CF provides estimates rather than a definitive assessment of cognitive function, it was shown that the KDQOL-CF scale scores correlate with the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination, and are acceptable for estimating cognitive function in dialysis subjects[12,29].

In the general population, IBS is associated with stress[6]. In our study, the presence of IBS compatible symptoms was not related to the presence or absence of anxiety or depression. This is similar to the findings by Cano and colleagues[2]. They, therefore, concluded that IBS in HD patients might be related to either the “uremic” state or the treatment method. This is in contrast to Kahvecioglu et al[4] who found that IBS in dialyzed patients was associated with depression and anxiety. In the general population, IBS seems to be more common in younger people. Our population was mostly over 50 years, and that might explain the lack of an age effect on the frequency of IBS symptoms.

Patients suffering from diabetes mellitus report a greater prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms than controls, which is not related to glycemic control[30]. We did not observe, however, any difference in the frequency of IBS symptoms between diabetic and non-diabetic HD patients. This is in agreement with Cano et al[2].

It is difficult to offer an explanation for the unexpected univariate association between IBS symptoms and hemoglobin level. Patients dialyzed in central and eastern European dialysis centers have lower mean hemoglobin levels and are less likely to attain target levels than those treated in western European counterparts[31]. HD patients with higher hemoglobin levels report higher quality of life, and IBS patients in the general population have lower health-related quality of life[32]. Additionally, gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with chronic kidney disease are associated with impaired general psychological well-being[5]. However, IBS patients have a propensity to report pain and label negatively expected adversive sensations, so it is conceivable that IBS specific symptoms are “unmasked” in patients who have an overall higher quality of life.

To our knowledge, the association between serum potassium level and the frequency of symptoms compatible with IBS has not been reported before. This finding, however, has to be treated with caution. Although gastrointestinal motility is impaired in chronic pre-dialysis kidney disease[33], it is alleviated by hemodialysis[34]. Thus, another mechanism may be responsible. Hypokalemia may cause decreased motility and propulsive activity of the intestine, and even lead to ileus. We recorded potassium levels before and after a single HD session, whereas a level prevailing over a specific time period might be more appropriate. It may be, however, that episodes of hypokalemia, which are likely just after hemodialysis, are responsible for the appearance of IBS symptoms. A consistent trend of a higher prevalence of IBS compatible symptoms with lower potassium concentration, also suggests a causative role for hypokalemia. During conventional HD, large amounts of potassium are removed, approximately 40% of which originates from the extra- and the remainder from the intracellular space[35]. A change in the plasma potassium concentration during hemodialysis, however, is difficult to predict, due to the concomitant movement of the ion into cells due to correction of metabolic acidosis. After HD, plasma potassium concentration increases rapidly during the first hour and steadily thereafter. The post-dialysis rise in potassium concentration is not correlated with pre- or post-dialysis plasma K[35].

In CAPD patients, it has been reported that episodes of hypokalemia are a risk factor for developing peritonitis and bacterial overgrowth, possibly due to altered intestinal motility[36,37].

In our study, neither the dialysis session time nor the change in potassium level influenced the prevalence of IBS symptoms, what suggests that the between dialyses level rather than the intradialytic change is important. In line with this electrophysiological mechanism reasoning, is the observation that pre-dialysis potassium < 4.0 or > 5.6 mEq/L is associated with increased mortality in HD patients, most probably due to cardiac arrhythmias[38]. Despite the plausible electrophysiological mechanism, the association between potassium level and IBS symptoms might be confounded by other factors. It has been suggested for both HD and PD patients, that hypokalemia could be a surrogate marker for poor nutrition and associated comorbidities[38,39].

This study has a number of shortcomings: firstly the Bowel Disease Questionnaire was not formally validated. To that end we ensured that the Polish translation was faithful and easy to understand. Additionally, the number of subjects was rather low, the study was observational and could not prove causality in relationships. Finally, the study potentially lacked generalizability due to cross-cultural differences in the symptomatology of functional gastrointestinal disorders[15].

In summary, this study examined potential risk factors for symptoms compatible with IBS in HD patients and identified an association with acetaminophen use, serum potassium level, and KDQOL-cognitive function score. The role of hypokalemia requires further well designed and controlled clinical studies.

Chronic gastrointestinal symptoms are very common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) treated by hemodialysis (HD) including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Risk factors associated with IBS in HD patients are not known.

Risk factors that are associated with IBS in the general population include: somatic symptoms, female gender, psychological distress, physical and sexual abuse, food allergies, enteric infections, previous abdominal surgeries, analgesic use, and food allergies and sensitivities. Of the 196 HD patients included in this study, symptoms compatible with IBS were present in 27 (13.8%) subjects and were independently associated with low post-dialysis serum potassium, paracetamol use, and KDQOL cognitive function score.

This study showed that low post-dialysis serum potassium, paracetamol use, and KDQOL cognitive function score are independently associated with increased risk of IBS compatible symptoms.

This analysis of the risk factors for IBS may be helpful in reducing the risk of abdominal symptoms in HD patients.

The authors report an observational study looking at various factors associated with IBS as defined by Manning criteria in haemodialysis patients.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Julian RF Walters, PhD, MD, BSc, MBBS, Department of Gastroenterology, Imperial College London, Hammersmith Hospital, Du Cane Road, London, W120HS, United Kingdom

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Abu Farsakh NA, Roweily E, Rababaa M, Butchoun R. Brief report: evaluation of the upper gastrointestinal tract in uraemic patients undergoing haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:847-850. |

| 2. | Cano AE, Neil AK, Kang JY, Barnabas A, Eastwood JB, Nelson SR, Hartley I, Maxwell D. Gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing treatment by hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1990-1997. |

| 3. | Hammer J, Oesterreicher C, Hammer K, Koch U, Traindl O, Kovarik J. Chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in hemodialysis patients. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1998;110:287-291. |

| 4. | Kahvecioglu S, Akdag I, Kiyici M, Gullulu M, Yavuz M, Ersoy A, Dilek K, Yurtkuran M. High prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome and upper gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with chronic renal failure. J Nephrol. 2005;18:61-66. |

| 5. | Strid H, Simrén M, Johansson AC, Svedlund J, Samuelsson O, Björnsson ES. The prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with chronic renal failure is increased and associated with impaired psychological general well-being. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1434-1439. |

| 6. | American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2105-2107. |

| 7. | Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Assessment of functional gastrointestinal disease: the bowel disease questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:1456-1479. |

| 8. | Manning AP, Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Morris AF. Towards positive diagnosis of the irritable bowel. Br Med J. 1978;2:653-654. |

| 9. | Talley NJ, Gabriel SE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW. Medical costs in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1736-1741. |

| 10. | Hayes RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Amin N, Carter WB. Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form (KDQOL-SF), Version 1.3: A Manual for Use and Scoring. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation 1995; . |

| 11. | Lopes AA, Bragg J, Young E, Goodkin D, Mapes D, Combe C, Piera L, Held P, Gillespie B, Port FK. Depression as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization among hemodialysis patients in the United States and Europe. Kidney Int. 2002;62:199-207. |

| 12. | Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Bliwise DL. Association of sleep difficulty with Kidney Disease Quality of Life cognitive function score reported by patients who recently started dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:284-289. |

| 13. | Hungin AP, Whorwell PJ, Tack J, Mearin F. The prevalence, patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40,000 subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:643-650. |

| 14. | Mearin F, Badía X, Balboa A, Baró E, Caldwell E, Cucala M, Díaz-Rubio M, Fueyo A, Ponce J, Roset M. Irritable bowel syndrome prevalence varies enormously depending on the employed diagnostic criteria: comparison of Rome II versus previous criteria in a general population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1155-1161. |

| 15. | Sperber AD. The challenge of cross-cultural, multi-national research: potential benefits in the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:351-360. |

| 16. | Drossman DA. The Rome criteria process: diagnosis and legitimization of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2803-2807. |

| 17. | Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. |

| 18. | Boyce PM, Koloski NA, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome according to varying diagnostic criteria: are the new Rome II criteria unnecessarily restrictive for research and practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3176-3183. |

| 19. | Camilleri M, Choi MG. Review article: irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:3-15. |

| 20. | Kruis W, Thieme C, Weinzierl M, Schüssler P, Holl J, Paulus W. A diagnostic score for the irritable bowel syndrome. Its value in the exclusion of organic disease. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1-7. |

| 21. | Ford AC, Talley NJ, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Vakil NB, Simel DL, Moayyedi P. Will the history and physical examination help establish that irritable bowel syndrome is causing this patient's lower gastrointestinal tract symptoms? JAMA. 2008;300:1793-1805. |

| 22. | Horwitz BJ, Fisher RS. The irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1846-1850. |

| 23. | Locke GR 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Melton LJ. Risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: role of analgesics and food sensitivities. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:157-165. |

| 24. | Kurella M, Luan J, Yaffe K, Chertow GM. Validation of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL) cognitive function subscale. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2361-2367. |

| 25. | Kurella M, Mapes DL, Port FK, Chertow GM. Correlates and outcomes of dementia among dialysis patients: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2543-2548. |

| 26. | Murray AM, Tupper DE, Knopman DS, Gilbertson DT, Pederson SL, Li S, Smith GE, Hochhalter AK, Collins AJ, Kane RL. Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients is common. Neurology. 2006;67:216-223. |

| 27. | Attree EA, Dancey CP, Keeling D, Wilson C. Cognitive function in people with chronic illness: inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Appl Neuropsychol. 2003;10:96-104. |

| 28. | Dancey CP, Attree EA, Stuart G, Wilson C, Sonnet A. Words fail me: the verbal IQ deficit in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:852-857. |

| 29. | Kurella M, Chertow GM, Luan J, Yaffe K. Cognitive impairment in chronic kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1863-1869. |

| 30. | Quan C, Talley NJ, Jones MP, Howell S, Horowitz M. Gastrointestinal symptoms and glycemic control in diabetes mellitus: a longitudinal population study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:888-897. |

| 31. | Wiecek A, Covic A, Locatelli F, Macdougall IC. Renal anemia: comparing current Eastern and Western European management practice (ORAMA). Ren Fail. 2008;30:267-276. |

| 32. | Rey E, García-Alonso MO, Moreno-Ortega M, Alvarez-Sanchez A, Diaz-Rubio M. Determinants of quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:1003-1009. |

| 33. | Hirako M, Kamiya T, Misu N, Kobayashi Y, Adachi H, Shikano M, Matsuhisa E, Kimura G. Impaired gastric motility and its relationship to gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with chronic renal failure. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1116-1122. |

| 34. | Adachi H, Kamiya T, Hirako M, Misu N, Kobayashi Y, Shikano M, Matsuhisa E, Kataoka H, Sasaki M, Ohara H. Improvement of gastric motility by hemodialysis in patients with chronic renal failure. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2007;43:179-189. |

| 35. | Blumberg A, Roser HW, Zehnder C, Müller-Brand J. Plasma potassium in patients with terminal renal failure during and after haemodialysis; relationship with dialytic potassium removal and total body potassium. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:1629-1634. |

| 36. | Chuang YW, Shu KH, Yu TM, Cheng CH, Chen CH. Hypokalaemia: an independent risk factor of Enterobacteriaceae peritonitis in CAPD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1603-1608. |

| 37. | Shu KH, Chang CS, Chuang YW, Chen CH, Cheng CH, Wu MJ, Yu TM. Intestinal bacterial overgrowth in CAPD patients with hypokalaemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1289-1292. |

| 38. | Kovesdy CP, Regidor DL, Mehrotra R, Jing J, McAllister CJ, Greenland S, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Serum and dialysate potassium concentrations and survival in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:999-1007. |

| 39. | Szeto CC, Chow KM, Kwan BC, Leung CB, Chung KY, Law MC, Li PK. Hypokalemia in Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients: prevalence and prognostic implication. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:128-135. |