Published online Apr 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i13.1787

Revised: November 3, 2010

Accepted: November 10, 2010

Published online: April 7, 2011

Therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the mainstay treatment for bile duct disease. The procedure is difficult per se, especially when a side-viewing duodenoscope is used, and when the patient has altered anatomical features, such as colonic interposition. Currently, there is no consensus on the standard approach for therapeutic ERCP in patients with total esophagectomy and colonic interposition. We describe a novel treatment design that involves the use of a side-viewing duodenoscope to perform therapeutic ERCP in patients with total esophagectomy and colonic interposition. A gastroscope was initially introduced into the interposed colon and a radio-opaque standard guidewire was advanced to a distance beyond the papilla of Vater, before the gastroscope was withdrawn. A side-viewing duodenoscope was then introduced along the guidewire under fluoroscopic guidance. After cannulation into the papilla of Vater, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) revealed a filling defect (maximum diameter: 15 cm) at the distal portion of the common bile duct (CBD). This defect was determined to be a stone, which was successfully retrieved by a Dormia basket after complete sphincterotomy. With this treatment design, it is possible to perform therapeutic ERCP in patients with colonic interposition, thereby precluding the need for percutaneous drainage or surgery.

- Citation: Yii CY, Chou JW, Peng YC, Chow WK. Application of a wire-guided side-viewing duodenoscope in total esophagectomy with colonic interposition. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(13): 1787-1790

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i13/1787.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i13.1787

The application of a side-viewing duodenoscope in total esophagectomy with colonic interposition is technically difficult, because of the altered structure of the colon and the redundancy of the endoscopic route. We report a wire-guided treatment designed to overcome this pitfall by introducing a side-viewing duodenoscope along a radio-opaque standard guidewire to facilitate therapeutic ERCP in patients undergoing esophagectomy with colonic interposition. The use of this treatment method ensured the safety of wire-guided therapeutic ERCP in patients undergoing total esophagectomy with colonic interposition.

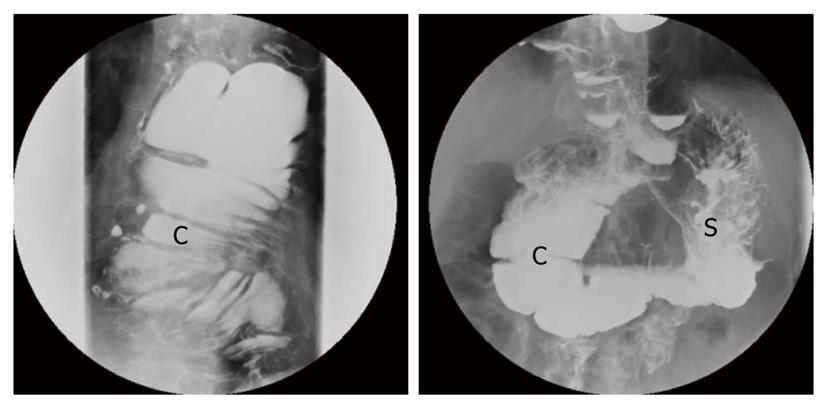

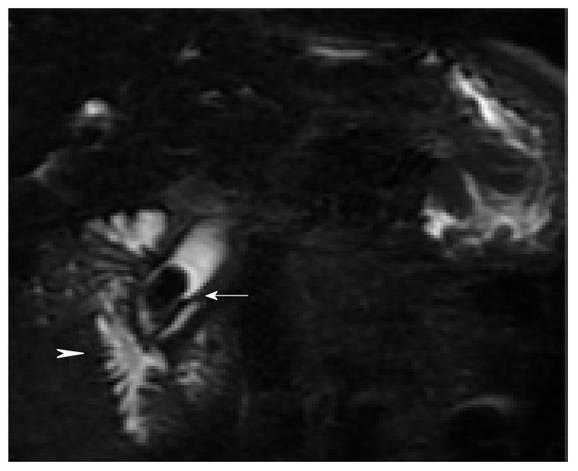

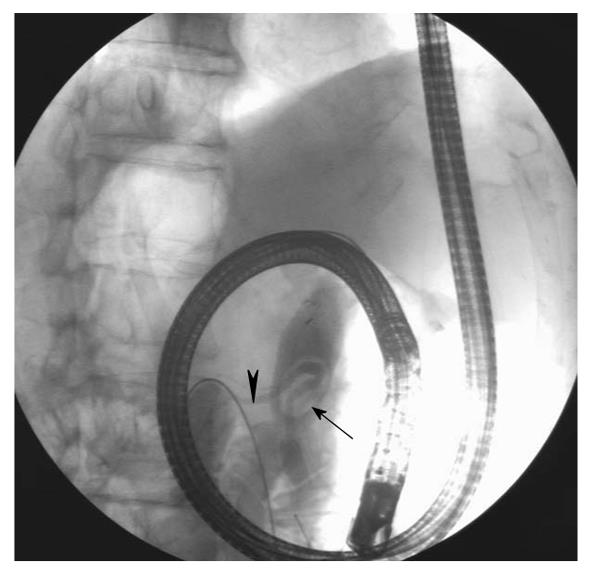

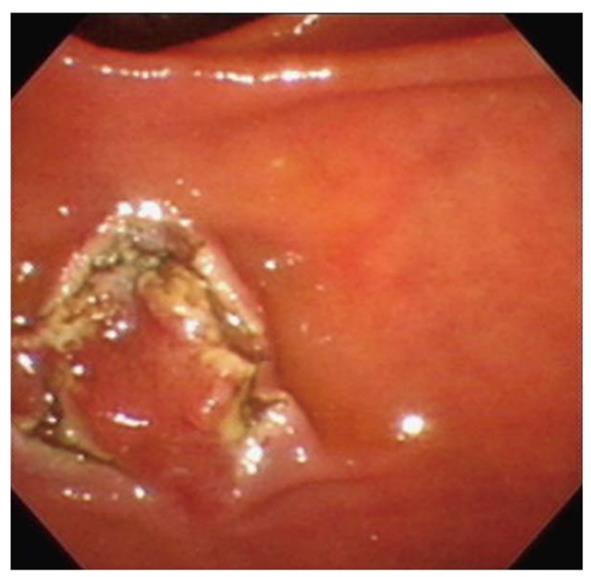

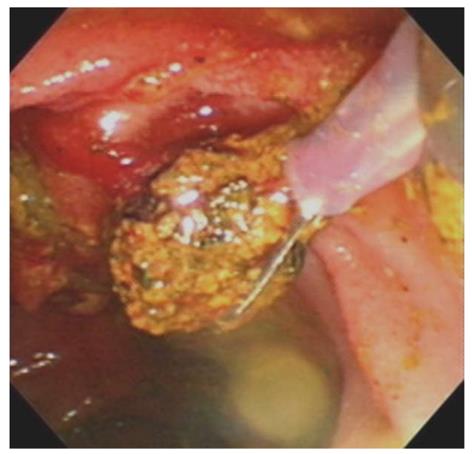

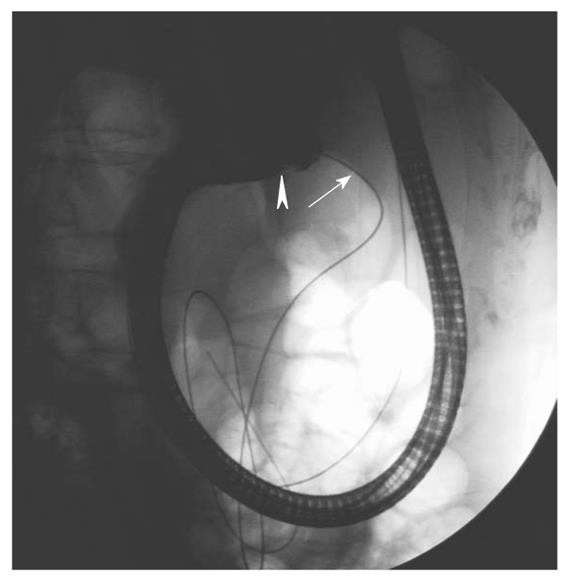

An 87-year-old man was referred to our hospital, a tertiary referral medical center, for the management of episodic fever, chills, and right upper quadrant abdominal pain, which had been occurring intermittently for two months. He had undergone total esophagectomy with colonic interposition 17 years ago for the treatment of intractable esophageal ulcers with massive bleeding (Figure 1). He denied having passed tea-colored urine or clay-colored stool. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed dilatation of the common hepatic duct (CHD) and common bile duct (CBD; diameter: 1.45 cm). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed the presence of a stone impacted at the distal portion of the CBD (Figure 2). The patient was intravenously administered midazolam (3 mg), pethidine (50 mg), and butylscopolamine (20 mg), and ERCP was performed with the patient in the left lateral position. A forward-viewing gastroscope (GIF-Q260, Olympus) was initially introduced; it was advanced through the interposed colonic segment, gastric remnant, and duodenum to reach the papilla of Vater. A radio-opaque standard guidewire (THSF-35-480, Wilson-Cook) was inserted deep into the small intestine, up to a distance beyond the papilla of Vater, via the accessory channel (Figure 3). The gastroscope was then withdrawn over-the-wire. Under fluoroscopic guidance, and with the patient in the left-lateral position, a side-viewing duodenoscope (TJF-240, Olympus) was introduced carefully along the guidewire until it reached the papilla of Vater. After cannulation with an ERCP catheter (StarTip cannula, PR-106Q-1, Olympus) as usual, cholangiography showed a filling defect (diameter, 1.5 cm) in the distal portion of the CBD; the lesion was determined to be a CBD stone (Figure 4). Complete sphincterotomy with a traction sphincterotome was performed (Figure 5). The pigmented stone was successfully retrieved using a Dormia basket (Figure 6). Subsequent balloon-occlusion cholangiography showed complete clearance of the CBD. The patient was followed up in the outpatient department and remains well.

The colon has been used as an esophageal substitute since 1911. It has been proven to be superior to other substitutes, such as the stomach and small intestine, because of it is length, acid resistance, and richness of vascular supply. It affords good overall satisfaction and allows maintenance of a wider surgical resection margin in patients with cancers of the gastroesophageal junction. The disadvantages of its application include prolonged operation time, extensive pre-operative preparation, and the late redundancy of colonic grafts[1,2].

Therapeutic ERCP with the application of a side-viewing duodenoscope is widely used in the management of pancreatic or hepatobiliary diseases, such as biliary stones[3]. Technically, it is difficult to advance a side-viewing duodenoscope through the colon because the duodenoscope affords visualization of only areas to the sides of the scope, and because of the presence of colonic interhaustral folds, the angulation of the colon, and the redundancy of the colonic graft[4]. To date, several techniques have been described for using the side-viewing duodenoscope to visualize the colon. Dafnis reported the successful application of a unique technique for approaching an inaccessible colonic polyp at the splenic flexure using an overtube to advance the side-viewing duodenoscope[5]. Another report of a case series on the management of inaccessible colonic polyps, advocated the technique of slightly bending the tip of the side-viewing duodenoscope, thereby providing a sloped-forward view for performing polypectomy[6]. We believe that the use of a wire-guided side-viewing duodenoscope might represent a safe technique for approaching inaccessible colonic polyps.

In the present case, our most important concern was the smooth advancement of the duodenoscope through the colonic graft. To address this concern, we inserted a radio-opaque guidewire to serve as a roadmap. Fry et al[7] reported an over-the-wire method by using a Super-Stiff Amplatz guidewire, which was actually designed for cardiac catheterization, to intubate the duodenum with a side-viewing duodenoscope in a patient with large paraesophageal hernia. The reason we chose the standard guidewire, instead of a Super-Stiff Amplatz guidewire, was because it is entirely radio-opaque. It facilitated the localization and visualization of the tip of the duodenoscope under close fluoroscopic guidance. Despite this, the duodenoscope did, at one point, move away from the appropriate path in the gastrointestinal tract, during the procedure. When the graft lumen could not be visualized on the endoscopic screen, we pushed the duodenoscope forward once its axis was the same as that of the wire, as determined by fluoroscopy; the scope was advanced in this manner until the graft lumen could be seen (Figure 7). The duodenoscope was advanced through the graft, and the CBD stone was eventually retrieved.

Manipulation of the guidewire is an art. One of its principles is to avoid looping, especially in a spacious cavity, such as the stomach. In our experience, we have observed that the looping of the guidewire may cause the failure of esophageal or duodenal metallic stent implantation in patients with malignant obstruction. The looping of the guidewire could render it difficult to introduce the scope further. To avoid this looping, we advanced the tip of the guidewire to a distance beyond the papilla of Vater, instead of stopping within the stomach.

Some experienced endoscopists prefer to backload the guidewire through the working channel of the duodenoscope. However, we think that this is not feasible because the side-viewing characteristic, with its acute angle of elevation. Backloading would render it difficult to insert the duodenoscope and would increase the number of loops formed. Furthermore, the double-balloon enteroscope could not be applied in our case because it is a forward-viewing scope and lacks the angle of elevation required to support the use of ERCP accessories.

Another technique that could have been considered in the present case would be the direct introduction of the side-viewing duodenoscope without the initial use of the forward-viewing gastroscope; however, this would have made it difficult to clearly visualize the lumen, especially as this patient had undergone colonic interposition. Such an approach would be accompanied by a high risk of perforation. The successful application of our technique for performing therapeutic ERCP is proof of the feasibility of this technique. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the use of this novel technique for treating a CBD stone in a patient with esophagectomy and colonic interposition.

In conclusion, in cases with rare clinical presentations, it is necessary to carefully and accurately estimate possible hindrances and develop appropriate solutions to successfully overcome them.

Peer reviewer: Klaus Mönkemüller, MD, PhD, FASGE, Division of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, Marien Hospital, Josef-Albers-Str. 70, 46236 Bottrop, Germany.

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Yildirim S, Köksal H, Celayir F, Erdem L, Oner M, Baykan A. Colonic interposition vs. gastric pull-up after total esophagectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:675-678. |

| 2. | DeMeester SR. Colon interposition following esophagectomy. Dis Esophagus. 2001;14:169-172. |

| 3. | Cohen S, Bacon BR, Berlin JA, Fleischer D, Hecht GA, Loehrer PJ Sr, McNair AE Jr, Mulholland M, Norton NJ, Rabeneck L. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: ERCP for diagnosis and therapy, January 14-16, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:803-809. |

| 4. | Grisolano SW, Petersen BT. Use of a duodenoscope to identify and treat a colonic vascular malformation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:323-325. |

| 5. | Dafnis G. A novel technique for endoscopic snare polypectomy using a duodenoscope in combination with a colonoscope for the inaccessible colonic polyp. Endoscopy. 2006;38:279-281. |

| 6. | Frimberger E, von Delius S, Rösch T, Schmid RM. Colonoscopy and polypectomy with a side-viewing endoscope. Endoscopy. 2007;39:462-465. |

| 7. | Fry LC, Howell CA, Mönkemüller KE. Use of a super-stiff Amplatz guidewire to intubate the duodenum with a duodenoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:773-774. |