Published online Apr 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i13.1753

Revised: February 21, 2011

Accepted: February 28, 2011

Published online: April 7, 2011

AIM: To evaluate the esophageal motility and abnormal acid and bile reflux incidence in cirrhotic patients without esophageal varices (EV).

METHODS: Seventy-eight patients with liver cirrhosis without EV confirmed by upper gastroesophageal endoscopy and 30 healthy control volunteers were prospectively enrolled in this study. All the patients were evaluated using a modified protocol including Child-Pugh score, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, esophageal manometry, simultaneous ambulatory 24-h esophageal pH and bilirubin monitoring. All the patients and volunteers accepted the manometric study.

RESULTS: In the liver cirrhosis group, lower esophageal sphincter pressure (LESP, 15.32 ± 2.91 mmHg), peristaltic amplitude (PA, 61.41 ± 10.52 mmHg), peristaltic duration (PD, 5.32 ± 1.22 s), and peristaltic velocity (PV, 5.22 ± 1.11 cm/s) were all significantly abnormal in comparison with those in the control group (P < 0.05), and LESP was negatively correlated with Child-Pugh score. The incidence of reflux esophagitis (RE) and pathologic reflux was 37.18% and 55.13%, respectively (vs control, P < 0.05). And the incidence of isolated abnormal acid reflux, bile reflux and mixed reflux was 12.82%, 14.10% and 28.21% in patients with liver cirrhosis without EV.

CONCLUSION: Cirrhotic patients without EV presented esophageal motor disorders and mixed acid and bile reflux was the main pattern; the cirrhosis itself was an important causative factor.

- Citation: Zhang J, Cui PL, Lv D, Yao SW, Xu YQ, Yang ZX. Gastroesophageal reflux in cirrhotic patients without esophageal varices. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(13): 1753-1758

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i13/1753.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i13.1753

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common diseases in modern civilization, which greatly affects people’s health and quality of life[1]. GERD is defined as reflux of gastroduodenal content to the esophagus, and includes reflux esophagitis (RE), nonerosive reflux disease (NERD) and Barrett’s esophagus (BE). GERD originates from a disturbance in the structure and function of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) barrier, and dysfunctional esophageal motility coupled with a weak LES can cause uncoordinated propulsion, regurgitation of gastric and/or duodenal contents into the esophagus[2].

Gastroesophageal reflux consists of a broad mixture of oral-esophageal, gastric, and duodenal secretions. It is accepted that acid reflux plays an important role in the pathogenesis of GERD[3]. But the role of non-acid reflux is still a controversy[4,5], and some recent studies have shown that duodenogastroesophageal reflux (DGER) is another important causative factor in esophageal mucosal damage[6,7]. So the combination of esophageal pH and bilirubin monitoring is indispensable for a precise diagnostic test in acid and non-acid reflux of GERD.

GERD can be induced or aggravated under many conditions including liver diseases. It has been reported that in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux occurs at a high frequency (64%)[8]. Moreover, hepatic cirrhosis has a high morbidity and mortality due to the portal hypertension with the development of esophageal varices, and the possibility of a digestive hemorrhage and worsening of hepatic insufficiency[9-11]. It is important to identify predictive or aggravating factors and if possible, to prevent these factors. Esophageal motor disorders have been found to be associated with acid gastroesophageal reflux in cirrhotic patients with esophageal varices, and functional studies have shown decreased functions of the lower esophageal sphincter with low amplitude of primary peristalsis and acid clearance, which might attribute to a mechanical effect of the presence of varices[12]. It is still unclear whether the presence of cirrhosis itself presents as a causative factor for the onset of gastroesophageal reflux, and there are few studies on the incidence of acid reflux and DGER in the cirrhotic patients without esophageal varices. Therefore, this study was designed to evaluate the esophageal motility and abnormal acid and bile reflux incidence in cirrhotic patients without esophageal varices.

Seventy-eight patients with liver cirrhosis without EV confirmed by upper gastroesophageal endoscopy from March 2008 to November 2010 were prospectively enrolled to this study. All the patients were the inpatients of Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University. Patients with systemic diseases related to esophageal motor disorders and/or gastroesophageal reflux diseases (progressive systemic sclerosis, diabetes mellitus, neuromuscular disorders), alcohol abusers within 6 mo and chronic drug users that influence esophageal motility (such as theophylline, nitrates and calcium channel blockers) were excluded.

All the patients were evaluated by the same physician according to a modified protocol including Child-Pugh score[13], ascites, and other complications and a reflux disease questionnaire (RDQ; AstraZeneca R and D, Wuxi, China). RDQ is a detailed questionnaire regarding the severity and frequency of four symptoms: heartburn, acid regurgitation, food regurgitation, and retrosternal pain, and each symptom is graded in severity and frequency. The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was verified by the clinical, laboratory, radiologic and histopathological results according to the criteria of the Chinese Medical Society for Liver Diseases[14].

Thirty healthy volunteers (15 women) with a mean age of 33 years served as controls in this study. None of them had a history of reflux disease or of surgery in the upper gastrointestinal tract or thorax. All the volunteers accepted the manometric study without medication.

The written informed consent for the study was approved by the hospital ethics committee, and obtained from all the subjects and the procedure followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. To exclude the EV cases, all patients received the upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination (OlympusXQ260; Olympus, Japan). Gastric varices and/or related congestive gastropathy were also recorded. Reflux esophagitis if present was classified according to the Los Angeles classification standards. Barrett’s esophagus was defined as a columnar-lined esophageal mucosa with intestinal metaplasia.

Esophageal manometry. Manometry was performed using a water-perfused manometric assembly (Medtronic, Deutschland). The manometric probe consisted of a 4.5-mm polyvinyl catheter (Medtronic) with eight measuring sites (0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 15, and 20 cm). The position, length and pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) were identified by the method of stepwise retraction of the probe through gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). After correct positioning of the catheter in the esophageal lumen, patients were asked to swallow ten 5-mL boluses of water. Manometric signals were recorded on a computer for subsequent display and analysis, and the information included: the length of the LES, antegrade and retrograde peristalses, synchronous and isolated contractile waves, peristaltic amplitude (PA), peristaltic duration (PD), and peristaltic velocity (PV) of primary peristaltic wave in distal esophagus. LES disorder and esophageal body dysmotility were diagnosed according to the criteria in a previous study[15].

Simultaneous ambulatory 24-h esophageal pH and bilirubin monitoring. After esophageal manometry, an antimony esophageal pH electrode and fiber optic probe for detecting acid and bilirubin were positioned pernasally 5 cm above the upper border of the LES and connected with an ambulatory pH recorder (Digitrapper Mk III 2000, Synetice Medical, Sweden) and an ambulatory duodenogastroesophageal reflux (DGER) monitoring system (Bilitic 2000, Synetice Medical, Sweden), respectively. The method was reported previously[16]. The recorded data were analyzed using the Synectics PM Software.

In brief, the 24-h pH ambulatory recording was carried out with a portable digital system composed of a catheter with an antimony electrode and external reference electrode. Patients were instructed to keep a diary recording the time of meals, position changes, and the time and type of their symptoms, and encouraged to pursue their normal daily activities and maintain their usual diet, avoiding citric fruit and soft drinks. Proton pump inhibitor if in use, were discontinued at least 7-10 d prior to the examination, H2 blockers at least 48-72 h and prokinetics agents 24 h. An esophageal pH of less than 4 for at least 15 s was considered to be a reflux episode. Pathological acid reflux was considered if the percentage of the time with the intraesophageal pH less than 4 was greater than 4%, the number of reflux episodes was larger than 50 or the DeMeester value was higher than 14.72[17].

The fiber optic spectrophotometer Bilitec 2000 was used to quantify DGER. The system consisted of a miniaturized probe measuring 1.5 mm in diameter that carried light signals into the esophagus and backed via a plastic fiberoptic bundle. Before each study, the probe was calibrated in water, and the probe tip was checked for obstruction after completion of the study.

Patients were also encouraged to maintain normal activities, sleep schedule, and to follow a particular low-fat diet containing light food elements, and not to take coffee, tea and fruit juice, in order to prevent any interference with the spectrophotometric recording. Skimmed milk and non-sparkling water were allowed. An episode of DGER was defined as an increase in esophageal bilirubin absorbance 0.14 for more than 10 s[18,19].

Blood samples were drawn for a complete analysis of blood cell count and levels of prothrombin, albumin, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), alkaline phosphatase, gamma glutamyl transferase, bilirubin, cholesterol, creatinine.

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical program SPSS 13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). All data were presented as mean ± SD, and P values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Seventy-eight patients met the inclusion criteria, 40 males (51.28%) and 38 females (48.72%), with a mean age of 56.41 ± 9.72 years (range, 18-75 years). Twenty-eight patients were classified as Child A, 27 as Child B and 23 as Child C patients. Typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease were present in 25 (32.05%) patients. The RDQ scores were significantly higher in liver cirrhosis group (11.32 ± 3.14) than in control group (6.25 ± 3.31) (P < 0.01). There were no statistical differences of RDQ scores among the liver cirrhosis subgroups, and no relationship between Child-Pugh score and abnormal reflux (P > 0.05).

In the liver cirrhosis group, LESP (15.32 ± 2.91 mm Hg), PA (61.41 ± 10.52 mmHg), PD (5.32 ± 1.22 s), and PV (5.22 ± 1.11 cm/s) were all significantly abnormal in comparison with those in the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 1). The results showed a gradual decrease of LESP and PA, also an extension of PD and PV in the liver cirrhosis group from Child A to Child C. LESP was negatively correlated with Child-Pugh score (P < 0.01, r = -0.625).

| Group | LESP (mmHg) | PA (mmHg) | PD (s) | PV (cm/s) |

| Liver cirrhosis (n = 78) | 15.32 ± 2.91a | 61.41 ± 10.52a | 5.32 ± 1.22a | 5.22 ± 1.11a |

| Child A (n = 28) | 16.18 ± 2.81 | 70.52 ± 8.93a | 3.91 ± 1.03a | 4.56 ± 1.22a |

| Child B (n = 27) | 15.41 ± 3.13c | 67.4 ± 9.3c | 5.11 ± 1.21c | 5.10 ± 1.02c |

| Child C (n = 23) | 14.52 ± 2.91e | 56.13 ± 10.06e | 6.02 ± 1.23e | 5.91 ± 1.01e |

| Control (n =30) | 16.21 ± 5.33 | 74.41 ± 17.53 | 2.70 ± 0.81 | 3.71 ± 1.82 |

The results demonstrated a stepwise increase of pathologic esophageal pH-metry in liver cirrhosis patients, and an increase of acid reflux episodes and percentage of a pH < 4 in the upright, supine and total phases of measurement (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Group | Number of acid reflux episodes | Number of acid reflux episodes lasting≥5 min | Mean time pH < 4 (%) | ||

| Total | Upright | Supine | |||

| Liver cirrhosis (n = 78) | 61.17 ± 33.35a | 15.25 ± 5.73a | 10.34 ± 4.45a | 5.22 ± 2.71a | 9.56 ± 3.42a |

| Child A (n = 28) | 51.24 ± 20.54a | 10.66 ± 7.28a | 8.11 ± 2.32a | 4.48 ± 1.76a | 7.32 ± 5.44a |

| Child B (n = 27) | 60.35 ± 18.66c | 12.35 ± 9.83c | 10.51 ± 1.62c | 5.64 ± 1.31c | 9.14 ± 4.37c |

| Child C (n = 23) | 73.52 ± 28.63e | 17.34 ± 12.46e | 12.34 ± 2.15e | 6.79 ± 1.51e | 11.56 ± 5.43e |

| Child D (n = 30) | 39.62 ± 29.32 | 4.81 ± 2.04 | 2.35 ± 1.53 | 3.58 ± 1.34 | 8.69 ± 3.45 |

The results showed a significant stepwise increase of pathologic esophageal bilirubin-metry in liver cirrhosis patients, along with significant increases of bile reflux episodes and percentage of absorbance > 0.14 in the upright, supine, and total phases of measurement (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

| Group | Number of bile reflux episodes | Number of bile reflux episodes lasting≥5 min | Mean time Abs > 0.14 (%) | ||

| Total | Upright | Supine | |||

| Liver cirrhosis (n = 78) | 36.53 ± 9.31a | 4.09 ± 1.15a | 6.73 ± 1.15a | 3.32 ± 1.05a | 4.37 ± 1.44a |

| Child A (n = 28) | 27.32 ± 10.31a | 3.85 ± 1.34a | 5.12 ± 1.45a | 3.15 ± 0.92a | 4.12 ± 0.97a |

| Child B (n = 27) | 39.46 ± 18.31c | 4.11 ± 1.65c | 6.54 ± 1.21c | 3.37 ± 1.13c | 5.04 ± 1.11c |

| Child C (n = 23) | 48.54 ± 26.41e | 4.23 ± 2.14e | 7.32 ± 1.34e | 4.28 ± 1.22e | 5.52 ± 1.12e |

| Control (n = 30) | 12.76 ± 6.97 | 2.15 ± 1.36 | 1.98 ± 0.86 | 1.03 ± 0.23 | 0.83 ± 0.62 |

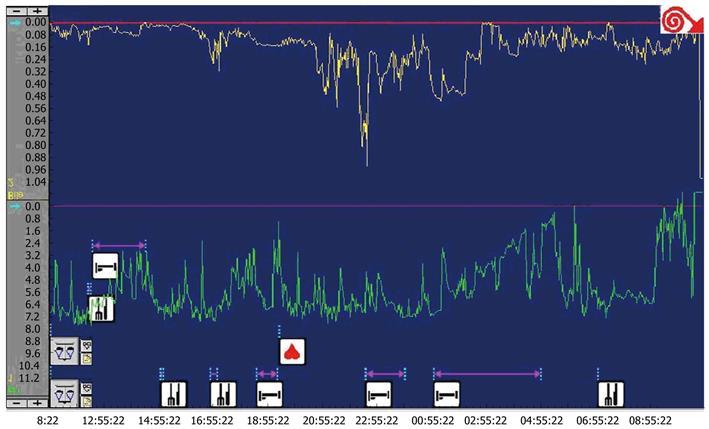

The incidence of RE and pathologic reflux was 37.18% and 55.13% in patients with liver cirrhosis, respectively, which were all higher than those in the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 4 and Figure 1). The incidence of isolated abnormal acid reflux, bile reflux and mixed reflux was 12.82%, 14.10% and 28.21% in patients with liver cirrhosis, respectively (Table 5). And the incidence of BE was 5.13% (4/78) in patients with liver cirrhosis, and none was found in the control group.

| Group | RE | Abnormal reflux |

| Child A (n = 28) | 8 (28.57) | 12 (42.86) |

| Child B (n = 27) | 11 (40.74) | 15 (55.56) |

| Child C (n = 23) | 10 (43.48) | 16 (69.57) |

| Total (n = 78) | 29 (37.18) | 43 (55.13) |

| Group | Isolated abnormal acid reflux | Isolated abnormal bile reflux | Mixed abnormal reflux | No abnormal reflux |

| Child A (n = 28) | 4 | 3 | 5 | 16 |

| Child B (n = 27) | 3 | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| Child C (n = 23) | 3 | 4 | 9 | 7 |

| Total (n = 78) | 10 (12.82%) | 11 (14.10%) | 22 (28.21%) | 35 (44.87%) |

As a complication of chronic liver disease, GERD in cirrhotic patients with EV accounted for about 20%, which mainly belongs to a dyskinetic type[20]. Previous studies found that esophageal varices played an important role in the development of esophageal motor disorders and abnormal gastroesophageal reflux in these patients, who presented obvious esophageal motor and motility disorders[21,22]. The most prevalent disorder was the inefficient esophageal motility, along with abnormal PA, PD and PV[12,21-23]. Some studies found that motor disorders existed in the esophageal body in these cirrhotic patients with EV, as compared with the cirrhotic patients without varices and control group[24]. Thus, it seemed that EV itself, independent of the cirrhosis, delayed esophageal clearance and increased the contact time between acid and mucosa.

In this study, LESP, PA, PD and PV in cirrhotic patients without esophageal varices were significantly abnormal as compared with those in the control group. LESP was markedly lower in patients with severe liver function damage, and negatively correlated with Child-Pugh score (P < 0.01, r = -0.625). The results showed that cirrhosis itself was another important factor for the esophageal motor disorder.

The incidence of esophageal acid reflux among cirrhotic patients with EV has also been studied in the last decades using pH-metry recording. It has been postulated that acid reflux may contribute to esophagitis and variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients, and it occurs at a high frequency (64%) in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension, irrespective of the etiology of cirrhosis and the grade of esophageal varices[8]. The results indicated that there was a correlation between typical gastroesophageal reflux disease and abnormal reflux, but no relationship between ascites, variceal size, congestive gastropathy and Child-pugh score and abnormal reflux.

The high incidence of RE in patients with severe chronic liver disease was also demonstrated, and asymptomatic RE was more common in cirrhotic and liver failure patients[25,26]. In the present study, abnormal reflux and RE were demonstrated in 55.13% and 37.18% of the cirrhotic patients without esophageal varices, and the more severe liver function damage, the more abnormal parameters of acid and bilirubin reflux. In the mean time, typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease were presented in only 32.05% of the cirrhotic patients in this study, and abnormal reflux was found in 62% of the patients in the night possibly due to the lowered esophageal defenses during this period, with reduction of saliva production, swallowing and esophageal clearance.

GERD may occur in acid, bile or a mixed form, and DGER is considered as an independent risk factor for complicated GERD. However, few studies have reported the incidence of DGER among cirrhotic patients. Patients with Barrett’s esophagus had significantly higher levels of DGER than patients with uncomplicated GERD, and bile reflux either alone or mixed with acid reflux contributed obviously to the severity of erosive and non-erosive reflux disease[6]. Moreover, DGER in acid medium was more injurious to the esophagus than DGER in alkaline pH[7]. We studied for the first time the incidence of BE and DGER in cirrhotic patients without esophageal varices. We found that the mixed acid and bile reflux was the predominant pattern of reflux in GERD patients, and the reflux incidence was also higher in Child B or C group than in Child A group. A stepwise increase of mixed reflux was demonstrated along with the severity of liver function damage. Four BE patients (2 with mixed abnormal reflux, 2 with DGER) were found in Child C group.

The causes and the mechanism of liver cirrhosis in patients with abnormal GERD have not been fully elucidated. In this study, we demonstrated an obvious esophageal motility disorder and abnormal gastroesophageal reflux in cirrhotic patients without esophageal varices, and abnormalities of esophageal motility and reflux parameter were correlated with the severity of liver function damage. It seemed that not only mechanical effect (EV), but also neural and humoral factor are related to the high incidence of GERD in patients with liver cirrhosis. The progress of liver dysfunction decreased the incidence of LESP, worsened the esophageal motility and the reflux in the cirrhotic patients. In some studies, the levels of plasma vasoactive peptides and neurotensin were markedly higher in patients with liver cirrhosis than in the normal population, which were also known to lower the pressure of the LES, facilitating the reflux of the stomach content[21,27].

The importance of nitrous oxide (NO) in the exacerbation of portal hypertension in liver cirrhosis was also reported[28,29]. This substance can be found in large amounts in the systemic circulation of cirrhotic patients, and NO concentration increased significantly in patients with liver disease, which was closely related to the transient LES relaxation, suggesting that NO played an important role in the process of GERD. Whether the excessive NO in cirrhotic patients could exacerbate these manifestations, needs to be further confirmed.

We found that gastric half-emptying of liquid food was delayed in patients with liver cirrhosis, and the function of gastric emptying was also influenced by the damaged liver function[30]. Ascites induced an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, compressing the stomach and the stomach content reflux[31].

In summary, the majority of cirrhotic patients without EV presented esophageal motor disorders; mixed acid and bile reflux was the main pattern of reflux in GERD patients; and the presence of cirrhosis itself was an important causative factor for the onset of gastroesophageal reflux. Further researches on the functional and humoral factors and mechanism of GERD in liver diseases will gain a broad attention and interest in this field.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common diseases in modern civilization, and it has been reported that gastroesophageal reflux disease occurs at a high frequency in patients with liver cirrhosis.

The relationship between esophageal motor disorders and acid gastroesophageal reflux in cirrhotic patients with esophageal varices has been reported. This study was designed to evaluate the esophageal motility and abnormal acid and bile reflux incidence in cirrhotic patients without esophageal varices.

This study showed that the presence of cirrhosis itself was an important causative factor for the onset of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with liver cirrhosis without varices. It is the first research on the incidence of Barrett’s esophagus and DGER in cirrhotic patients without esophageal varices.

This study helped better understand the mechanism of GERD in patients with liver cirrhosis, and contributed to the diagnosis and treatment of liver cirrhosis and its complications in clinical practice.

This is an interesting study on GERD in patients with liver cirrhosis, but without esophageal varices. Since it has before been thought that esophageal varices somehow have something to do with the increased frequency of GERD in patients with liver disease, the authors have made an interesting contribution to the literature by showing that reflux symptoms and pathologic esophageal motility changes are more common in patients with cirrhosis but without varices.

Peer reviewer: Helena Nordenstedt, MD, PhD, Upper Gastrointestinal Research, Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm 17176, Sweden

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Gisbert JP, Cooper A, Karagiannis D, Hatlebakk J, Agréus L, Jablonowski H, Nuevo J. Impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on work absenteeism, presenteeism and productivity in daily life: a European observational study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:90. |

| 2. | Cappell MS. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89:243-291. |

| 3. | Gutschow CA, Bludau M, Vallböhmer D, Schröder W, Bollschweiler E, Hölscher AH. NERD, GERD, and Barrett’s esophagus: role of acid and non-acid reflux revisited with combined pH-impedance monitoring. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3076-3081. |

| 4. | Green BT, O’Connor JB. Most GERD symptoms are not due to acid reflux in patients with very low 24-hour acid contact times. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1084-1087. |

| 5. | Tack J, Fass R. Review article: approaches to endoscopic-negative reflux disease: part of the GERD spectrum or a unique acid-related disorder? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19 Suppl 1:28-34. |

| 6. | Hak NG, Mostafa M, Salah T, El-Hemaly M, Haleem M, Abd El-Raouf A, Hamdy E. Acid and bile reflux in erosive reflux disease, non-erosive reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:442-447. |

| 7. | Elhak NG, Mostafa M, Salah T, Haleem M. Duodenogastroesophageal reflux: results of medical treatment and antireflux surgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:120-126. |

| 8. | Ahmed AM, al Karawi MA, Shariq S, Mohamed AE. Frequency of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40:478-480. |

| 9. | Millwala F, Nguyen GC, Thuluvath PJ. Outcomes of patients with cirrhosis undergoing non-hepatic surgery: risk assessment and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4056-4063. |

| 10. | Tangkijvanich P, Yee HF Jr. Cirrhosis--can we reverse hepatic fibrosis? Eur J Surg Suppl. 2002;100-112. |

| 11. | Mumtaz K, Ahmed US, Abid S, Baig N, Hamid S, Jafri W. Precipitating factors and the outcome of hepatic encephalopathy in liver cirrhosis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20:514-518. |

| 12. | Flores PP, Lemme EM, Coelho HS. [Esophageal motor disorders in cirrhotic patients with esophageal varices non-submitted to endoscopic treatment]. Arq Gastroenterol. 2005;42:213-220. |

| 13. | Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646-649. |

| 14. | Jia JD, Li LJ. [The guideline of prevention and treatment for chronic hepatitis B (2010 version).]. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2011;19:13-24. |

| 15. | Freys SM, Fuchs KH, Heimbucher J, Thiede A. Tailored augmentation of the lower esophageal sphincter in experimental antireflux operations. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:1183-1188. |

| 16. | Xu XR, Li ZS, Zou DW, Xu GM, Ye P, Sun ZX, Wang Q, Zeng YJ. Role of duodenogastroesophageal reflux in the pathogenesis of esophageal mucosal injury and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:91-94. |

| 17. | Martinez SD, Malagon IB, Garewal HS, Cui H, Fass R. Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)--acid reflux and symptom patterns. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:537-545. |

| 18. | Cuomo R, Koek G, Sifrim D, Janssens J, Tack J. Analysis of ambulatory duodenogastroesophageal reflux monitoring. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:2463-2469. |

| 19. | Tack J, Bisschops R, Koek G, Sifrim D, Lerut T, Janssens J. Dietary restrictions during ambulatory monitoring of duodenogastroesophageal reflux. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1213-1220. |

| 20. | Ueda A, Enjoji M, Kato M, Yamashita N, Horikawa Y, Tajiri H, Kotoh K, Nakamuta M, Takayanagi R. [Frequency of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) as a complication in patients with chronic liver diseases: estimation of frequency scale for the system of GERD]. Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi. 2007;98:373-378. |

| 21. | Grassi M, Albiani B, De Matteis A, Fontana M, Lucchetta MC, Raffa S. [Prevalence of dyspepsia in liver cirrhosis: a clinical and epidemiological investigation]. Minerva Med. 2001;92:7-12. |

| 22. | Suzuki K, Suzuki K, Koizumi K, Takada H, Nishiki R, Ichimura H, Oka S, Kuwayama H. Effect of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease on quality of life of patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:335-339. |

| 23. | Guo Q, Chen Y, Long Y. [Study on esophageal motility and its effect by EVL in patients with esophageal varices]. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 1999;7:201-202. |

| 24. | Passaretti S, Mazzotti G, de Franchis R, Cipolla M, Testoni PA, Tittobello A. Esophageal motility in cirrhotics with and without esophageal varices. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:334-338. |

| 25. | Schechter RB, Lemme EM, Coelho HS. Gastroesophageal reflux in cirrhotic patients with esophageal varices without endoscopic treatment. Arq Gastroenterol. 2007;44:145-150. |

| 26. | Li B, Zhang B, Ma JW, Li P, Li L, Song YM, Ding HG. High prevalence of reflux esophagitis among upper endoscopies in Chinese patients with chronic liver diseases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:54. |

| 27. | Richter JE. Role of the gastric refluxate in gastroesophageal reflux disease: acid, weak acid and bile. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338:89-95. |

| 28. | Okamoto E, Amano Y, Fukuhara H, Furuta K, Miyake T, Sato S, Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y. Does gastroesophageal reflux have an influence on bleeding from esophageal varices? J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:803-808. |

| 29. | Papadopoulos N, Soultati A, Goritsas C, Lazaropoulou C, Achimastos A, Adamopoulos A, Dourakis SP. Nitric oxide, ammonia, and CRP levels in cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy: is there a connection? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:713-719. |

| 30. | Souza RC, Lima JH. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review of this intriguing relationship. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:256-263. |

| 31. | Navarro-Rodriguez T, Hashimoto CL, Carrilho FJ, Strauss E, Laudanna AA, Moraes-Filho JP. Reduction of abdominal pressure in patients with ascites reduces gastroesophageal reflux. Dis Esophagus. 2003;16:77-82. |