Published online Jan 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i1.89

Revised: September 7, 2010

Accepted: September 14, 2010

Published online: January 7, 2011

AIM: To examine the relationship between the trends in food consumption and gastric cancer morbidity in Poland.

METHODS: The study was based on gastric cancer incidence rates and consumption of vegetables, fruit, vitamin C and salt in Poland between 1960 and 2006. Food consumption data were derived from the national food balance sheets or household budget surveys. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to estimate the relationship between the variables.

RESULTS: A negative correlation was found between vegetables (-0.70 both for men and women; P < 0.0001), fruit (-0.65 and -0.66; P < 0.0001) and vitamin C (-0.75 and -0.74; P < 0.0001) consumption and stomach cancer incidence rates. The same applied to the availability of refrigerators in the household (-0.77 and -0.80; P < 0.0001). A decline in these rates could also be linked to reduction in salt intake.

CONCLUSION: The decline of gastric cancer incidence probably resulted from increased consumption of vegetables, fruit and vitamin C and a decrease in salt consumption.

- Citation: Jarosz M, Sekuła W, Rychlik E, Figurska K. Impact of diet on long-term decline in gastric cancer incidence in Poland. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(1): 89-97

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i1/89.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i1.89

Gastric cancer ranks fourth in morbidity and second in mortality for malignant cancers worldwide[1]. However, in numerous countries, in particular in economically developed ones, gastric cancer morbidity within the past few decades has reduced significantly. Several epidemiological studies have shown that this phenomenon is most probably related to favorable changes in dietary pattern in the developed countries, that is, mostly to increased consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables, and decreased consumption of salt-preserved food[2] and greater availability of refrigerators[3]. It is assumed that lower gastric cancer morbidity rates are also related to lower prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, which is considered as an essential factor for the development of a majority of gastric cancers[4,5]. In these countries, prevalence of H. pylori infections affects 20%-40% of the population.

Against this background, Poland seems to be a particular case. Despite the fact that, according to national epidemiological studies, the percentage of people infected with H. pylori is unusually high and amounts to 73% of the total population and 85%-95% of those aged > 25 years[6], in 2006, gastric cancer morbidity rate was twofold lower compared to that in 1960[7,8].

What was the reason for such a significant decrease in morbidity rate, taking such widespread dissemination of H. pylori as a major carcinogen into consideration? This intriguing phenomenon might be most probably assigned to specific changes in dietary pattern, as in the case of western countries.

Data that reflect average food consumption per capita in Poland in 1950-2006 show that this period was highly diversified with regard to dietary trends[9-11]. In relation to the above, the two following periods can be distinguished: 1950-1989 and 1990-2006. Within the first period, consumption of products of animal origin (meat and meat products, animal fat, milk and dairy products, butter, fish and eggs) as well as sugar and sugar products showed a growing trend. At the same time, consumption of cereals and potatoes had decreased. Growth of vegetable consumption had come to an end in the 1950s and 1960s. Fruit consumption was low, particularly compared to other countries, due to frequent fluctuations in crops and limited fruit import, which was insufficient to mitigate the effect of such fluctuations.

Within the second period, a reversal in these trends was noticeable, particularly in relation to consumption of butter and other animal fats, red meat as well as milk and dairy products. This period was also characterized by a significant increase in fruit consumption and, despite no increasing trend, also in relatively high vegetable consumption[9-11].

The above-mentioned favorable phenomena are considered to have brought about a significant improvement in the health situation in Poland. It can be assumed that positive changes in diet have influenced the decline in overall mortality seen since 1992, and stabilization of total malignant cancer mortality as well as a significant decrease in morbidity.

Data on gastric cancer incidence rates were derived from the National Cancer Registry administered by the Maria Skłodowska-Curie Memorial Cancer Center and Institute of Oncology in Warsaw[7,8]. They showed standardized gastric cancer incidence rates for men and women covering individual years between 1960 and 2006, excepting 1984, 1986, 1997 and 1998, for which no such data were available; in the case of the missing data for 1997-1998, the physicians’ strike was the main contributing reason.

The source of information on the dietary pattern in the same time period was the database that was established and maintained for several decades by the National Food and Nutrition Institute[9-11]. This database covers both published and unpublished data derived from the national food balance sheets and shows major food quantities available for consumption per capita/year. They are converted into energy and nutrients with the use of a set of nutrient conversion factors developed at the institute and based on the national food composition tables[12]. The resultant estimates show energy and nutrient amounts derived from food and available for consumption per capita/d.

In Poland, no data on average consumption of table salt per capita over the long term are available. Such data are available only for the period before World War II[13]. After the war, this practice has not been continued. Data on salt consumption re-appeared, however, in 1998. They show average monthly consumption of salt per capita in households, which participated in budget surveys, carried out on annual basis using a sampling method that allowed for generalization of the results to all households in the country[14]; these data were used for the analyses in the present study.

The features of the data on food quantities available for consumption and the derived estimates of the amounts of energy and nutrients made them particularly useful in the analysis of the trends over time, and to compare them with the trends in the health situation. In such a way, they were utilized in the present study. The study was focused on identification and measurement of the relationship between gastric cancer incidence rates and variables related to dietary pattern represented by the consumption of fruit, vegetables, vitamin C and kitchen salt. A trend in the equipment of Polish households with refrigerators was taken into consideration also as an important factor that affected perishable food quality and protected against nutrient loss.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (rs) were estimated as a measure of the relationship between stomach cancer incidence rates and selected parameters.

Gastric cancer has a much higher incidence among men than women. In a base year of our analysis, i.e. 1960, the standardized rate for men amounted to 25.1/100 000, which exceeded twice the incidence rate for women (10.4/100 000)[7]. For men, this rate reached a maximum level in 1970 and was 38% higher compared to 1960. In the same year, the maximum morbidity level was observed among women also; the rate was 39% higher than in 1960. The following years brought a decline in morbidity, and in 2006, the rates for men and women were approximately two times lower compared to the base year[8].

Due to the fact that gastric cancer is one of two major types of cancer for which the risk is commonly agreed to be modified mainly by food and nutrition[15], correlations between morbidity rates and consumption of certain food products and nutrients, which had both a positive and negative impact on this type of cancer, were analyzed. Due to reliable evidence that diets rich in fruit and vegetables protect against gastric cancer, these groups of products were analyzed first.

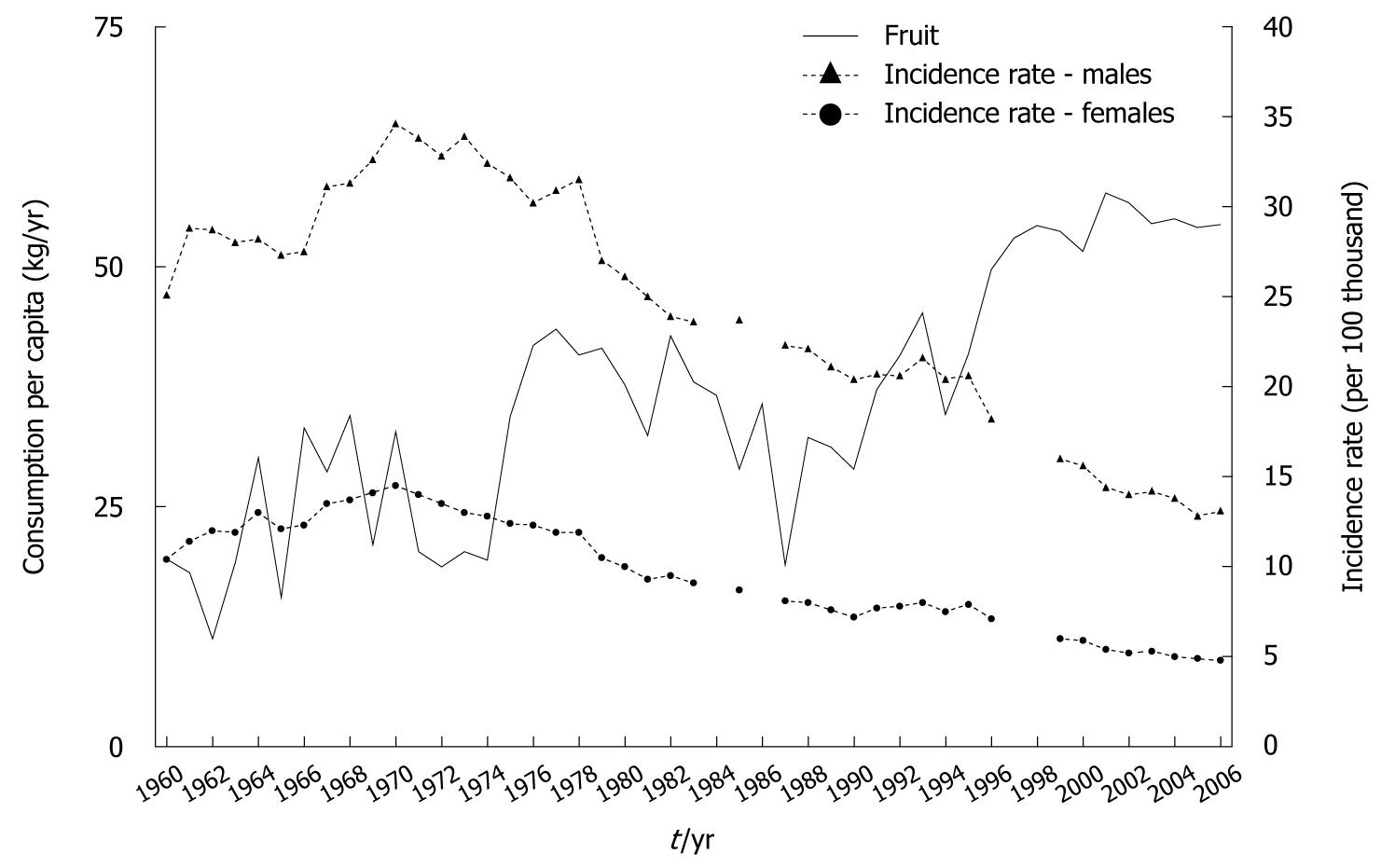

At the beginning of the 1960s, fruit was of minor importance in the average dietary pattern in our country, which resulted from low domestic production levels and no imports (Figure 1)[10]. In the following years, the role of fruit has been gradually increased due to its greater availability. A particular improvement has been observed within the past 12 years, i.e. after initiation of political, economic and social transformation, accompanied by an increase in domestic fruit production and import[9,11]. Also, changes in retail price relations between fruit and other food products have stimulated consumer demand for fruit and this has had a great impact.

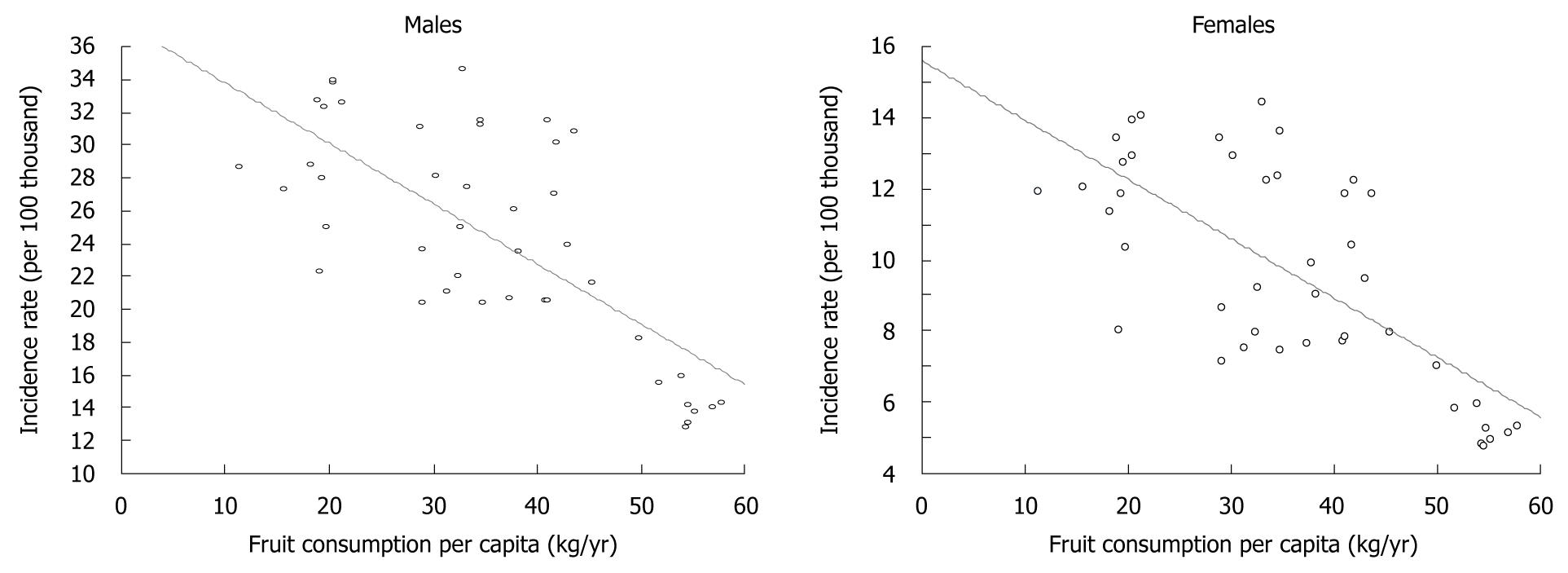

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, which covered fruit consumption in 1960-2006 and gastric cancer morbidity in the same period, showed a high correlation between the increase in fruit consumption and decrease in morbidity rate (Figure 2).

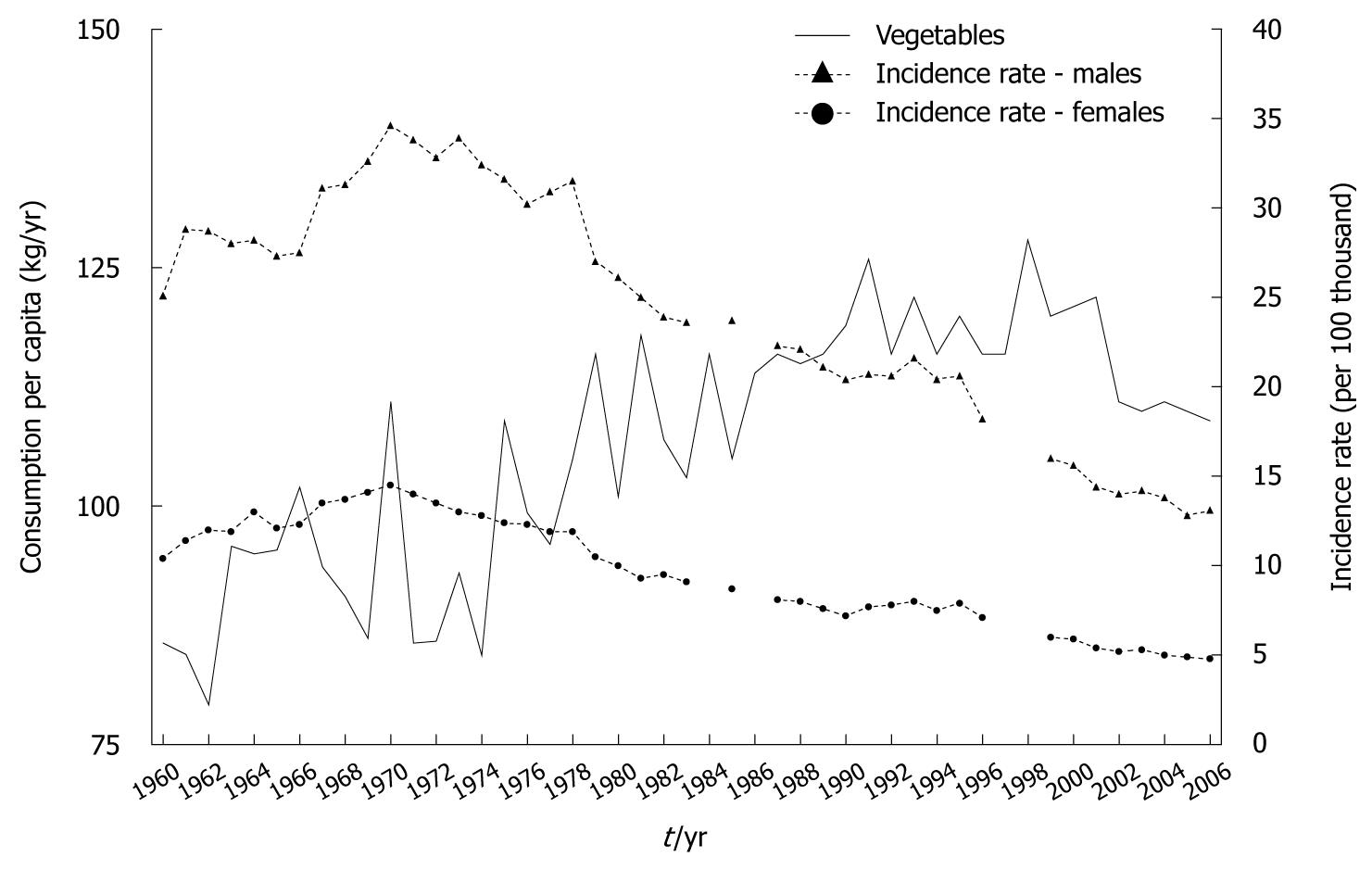

Vegetables traditionally have been more prominent than fruit in the dietary pattern in Poland, which has resulted from their greater availability and, in consequence, lower prices. Consumption of this group of products, similarly to fruit, has been subject to a growing trend, and in 2006 was almost 30% higher compared to 1960 (Figure 3)[9-11].

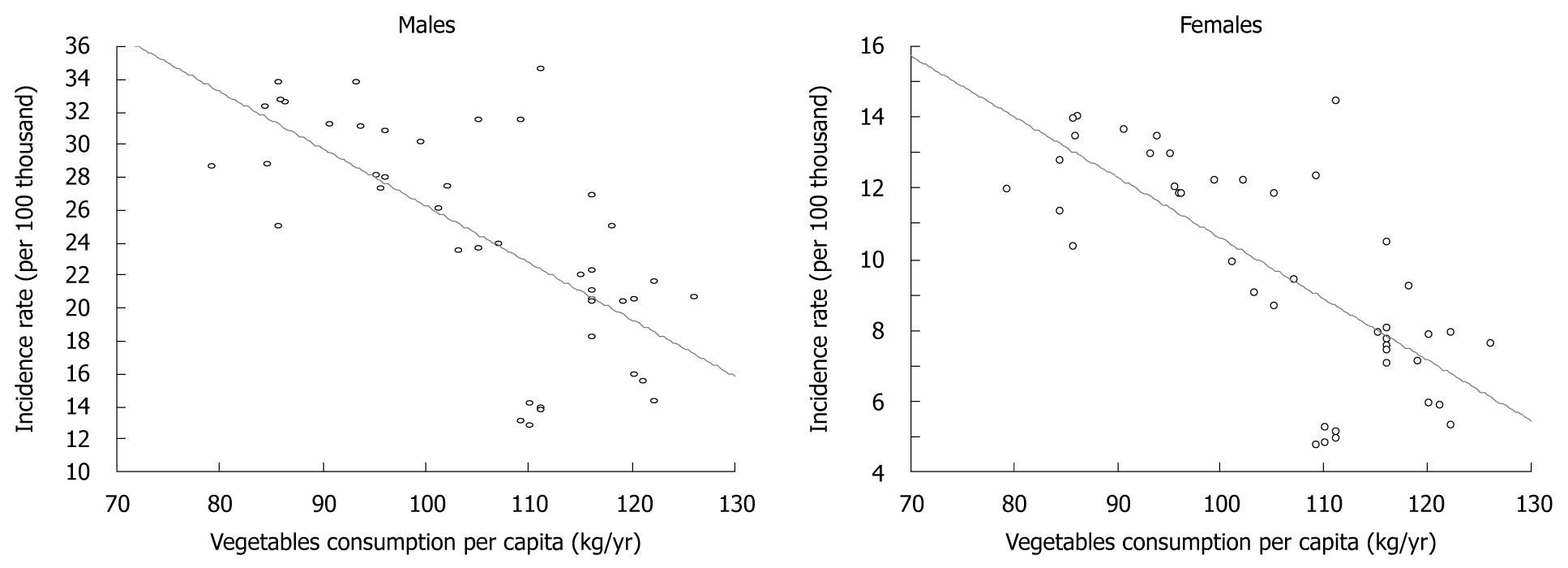

Estimate of the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient showed a very high correlation between the trend in vegetable consumption and gastric cancer morbidity (Figure 4).

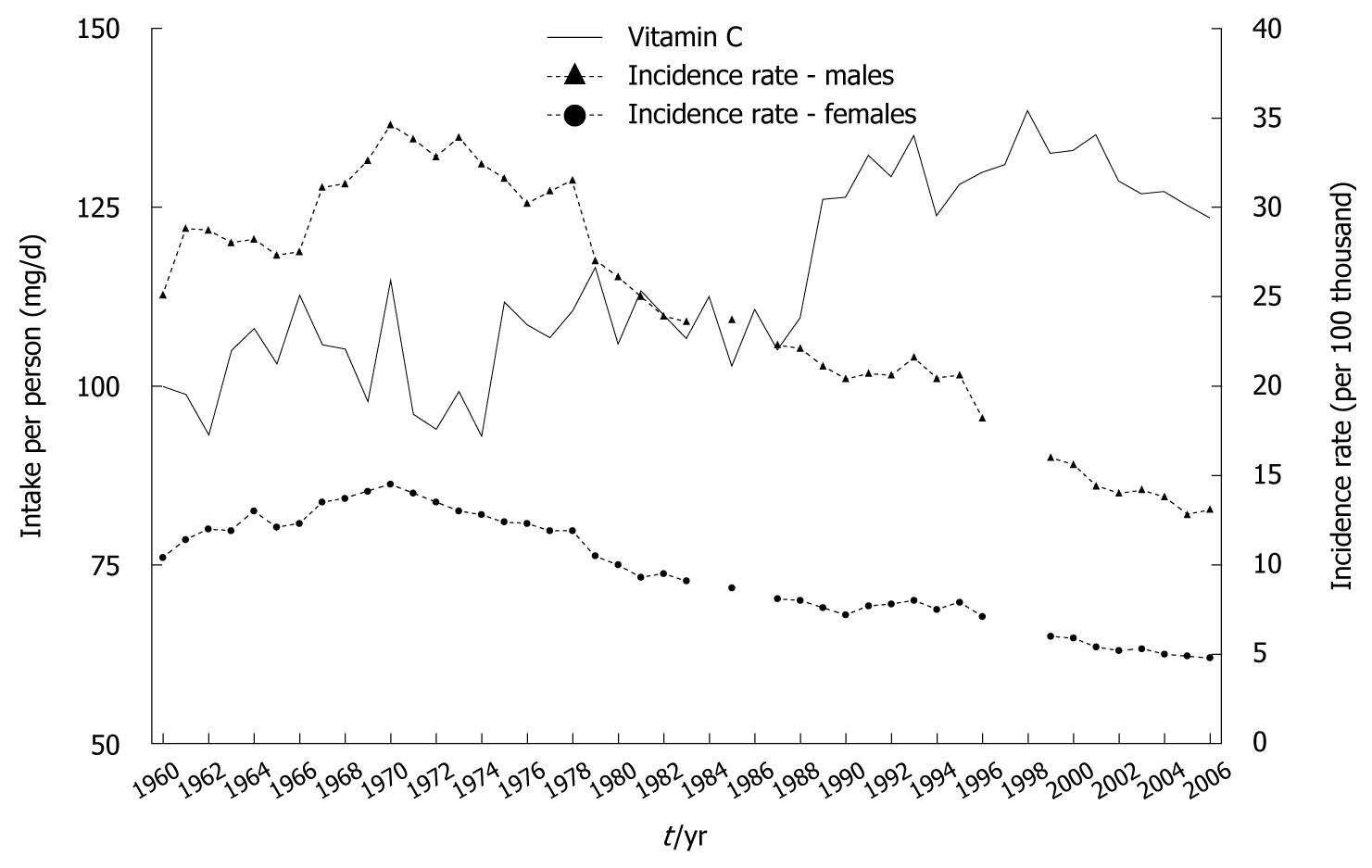

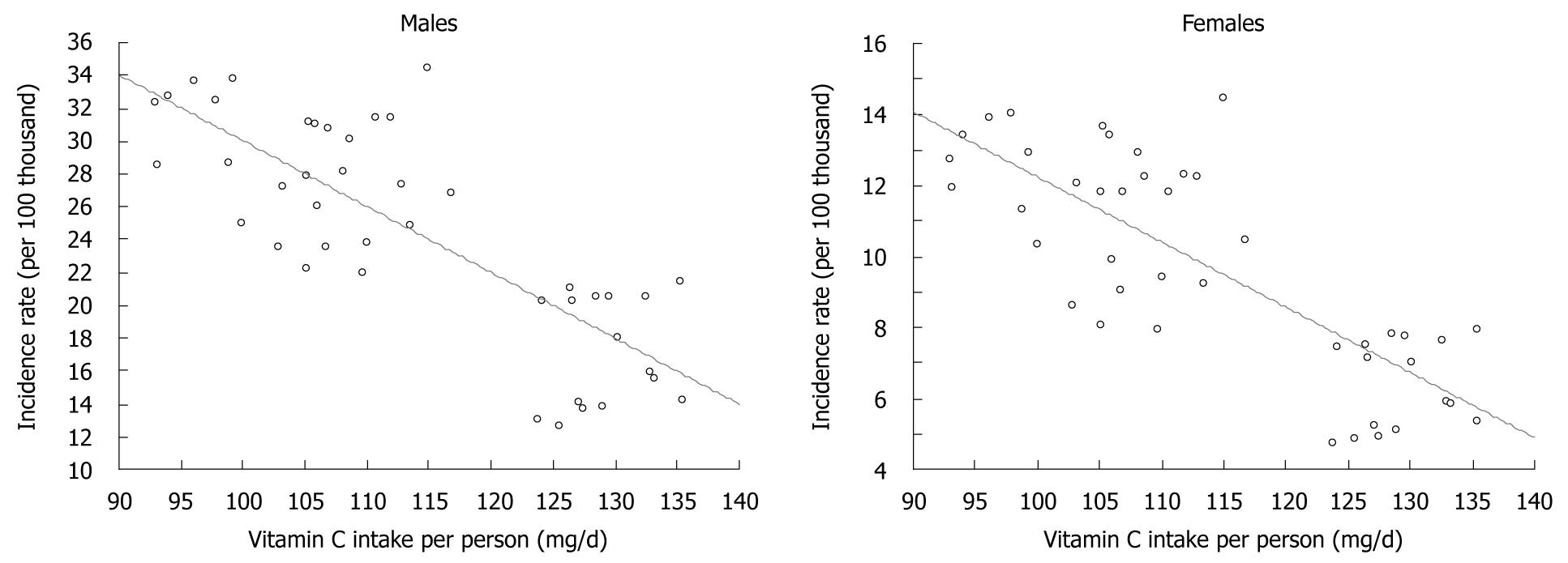

Increased consumption of both food groups resulted in the growth of vitamin C content in the diet, despite a reduction in potato consumption: total vitamin C content grew from approximate 100 mg/d in 1960 to 124 mg in 2006, and a rise in the proportion contributed by fruit and vegetables was noted (Figure 5)[9-11]. Calculations made for the purposes of this study showed a very high correlation between increased vitamin C intake and decreased gastric cancer morbidity (Figure 6).

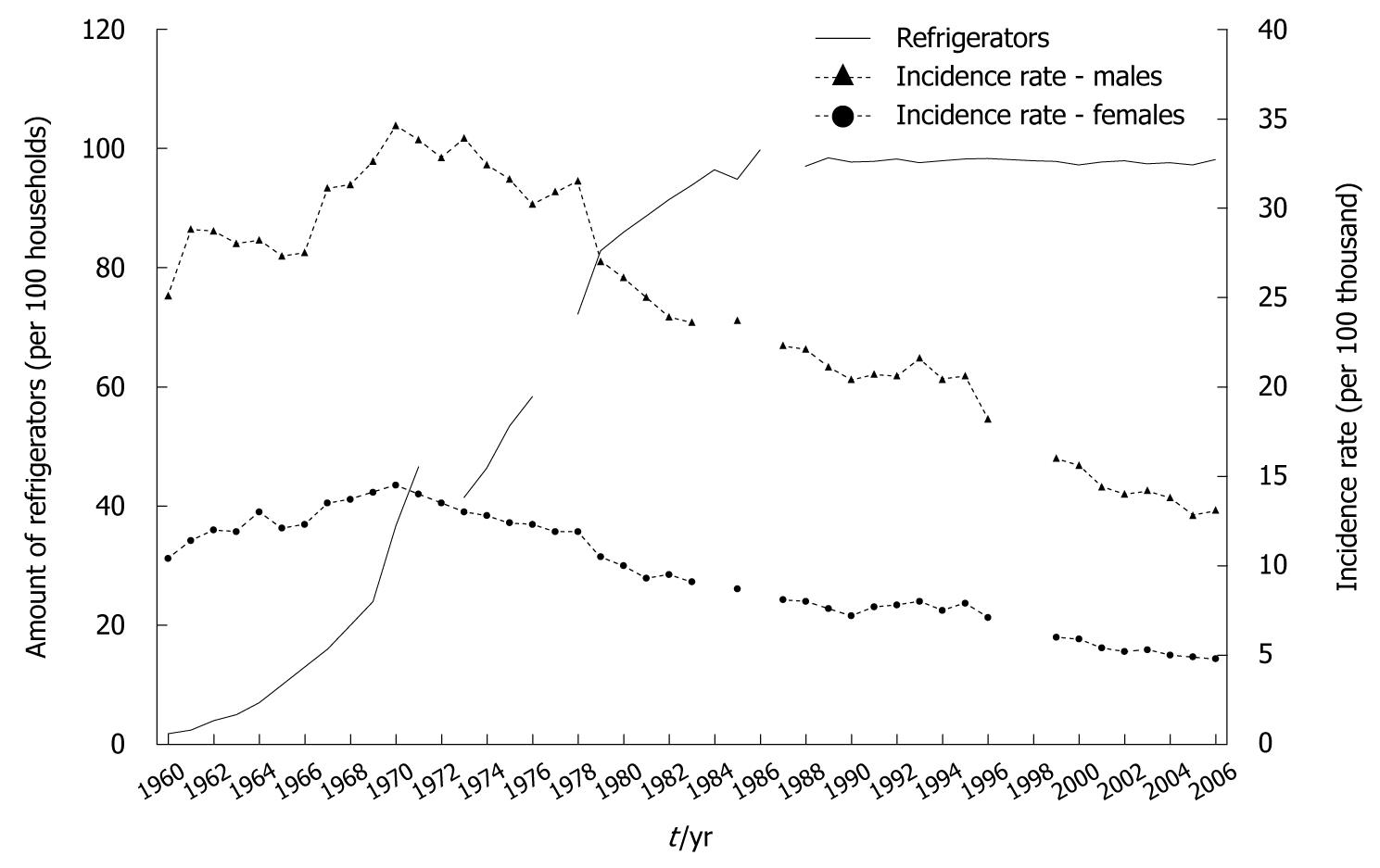

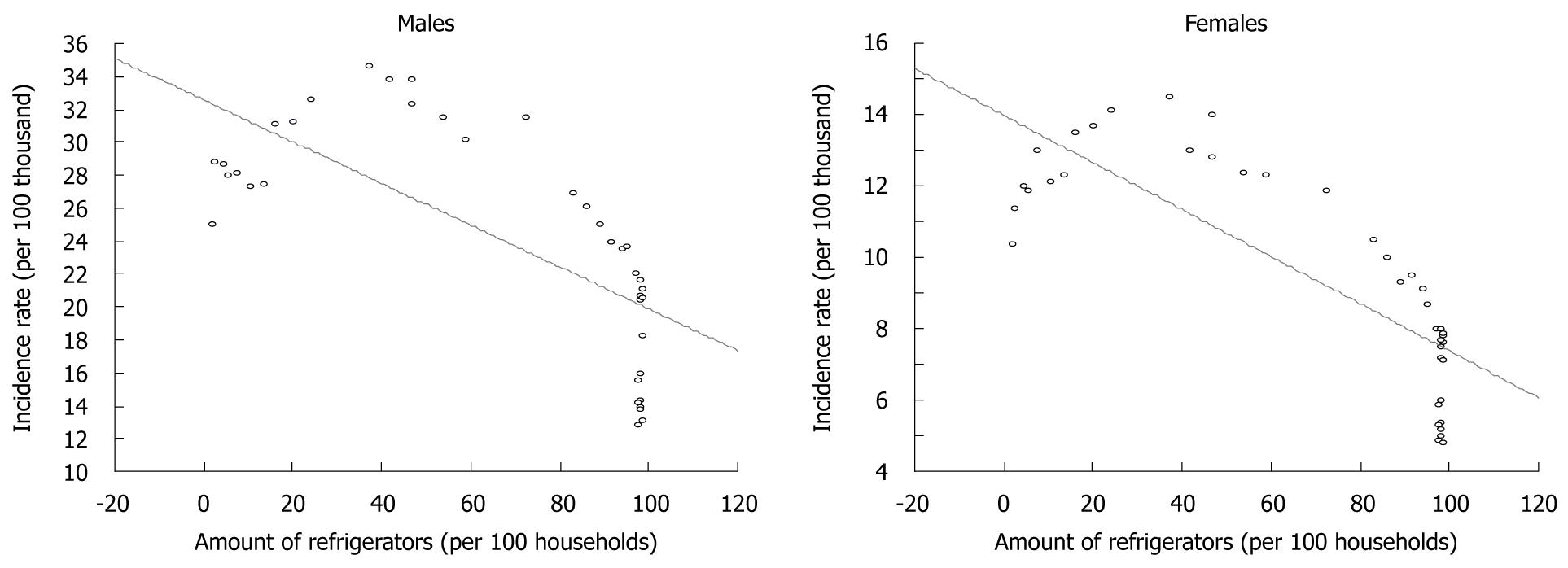

Reliable evidence that confirmed that storing food in refrigerators protects against gastric cancer[15-17] has focused attention on the trend in their availability in Polish households. This equipment has become popular relatively late in our country. In 1960, there were only an average of 1.8 refrigerators per 100 households, which contrasts with western countries (Figure 7). The above situation has also related to the availability of refrigerators in the retail and catering trades.

Up to 1970, the number of refrigerators increased to approximate 37 per 100 households, although still only about one-third of the total number of households. Only at the beginning of the 1980s were > 90% of households equipped with refrigerators.

Estimates made for the purposes of this study demonstrated a very high correlation between the equipment of households with refrigerators and gastric cancer morbidity (Figure 8).

It has been proven that diets with high salt content have an unfavorable effect on gastric cancer. Consumption of table salt in 1929 amounted to 9.9 kg per capita (27 g/d), and decreased to 8.4 kg in 1938 (23 g/d). Despite the decrease, this amount was still very high, which resulted mainly from its common usage as a preserving agent, which in turn, was determined by insufficient development of commercial food processing. Slow progress in this area in the early years after World War II allows us to assume that salt consumption was maintained at the same very high level observed in the pre-war period, and then decreased. According to the results of household budget surveys, table salt consumption in 2006 amounted to 0.25 kg/mo per person, that is, 3 kg/year (8.2 g/d)[14]. This is almost threefold lower compared to consumption in 1938, but the fact that data from food balance sheets and budget surveys are not fully comparable should be mentioned. Despite this reservation, the decrease in salt consumption is unquestionable.

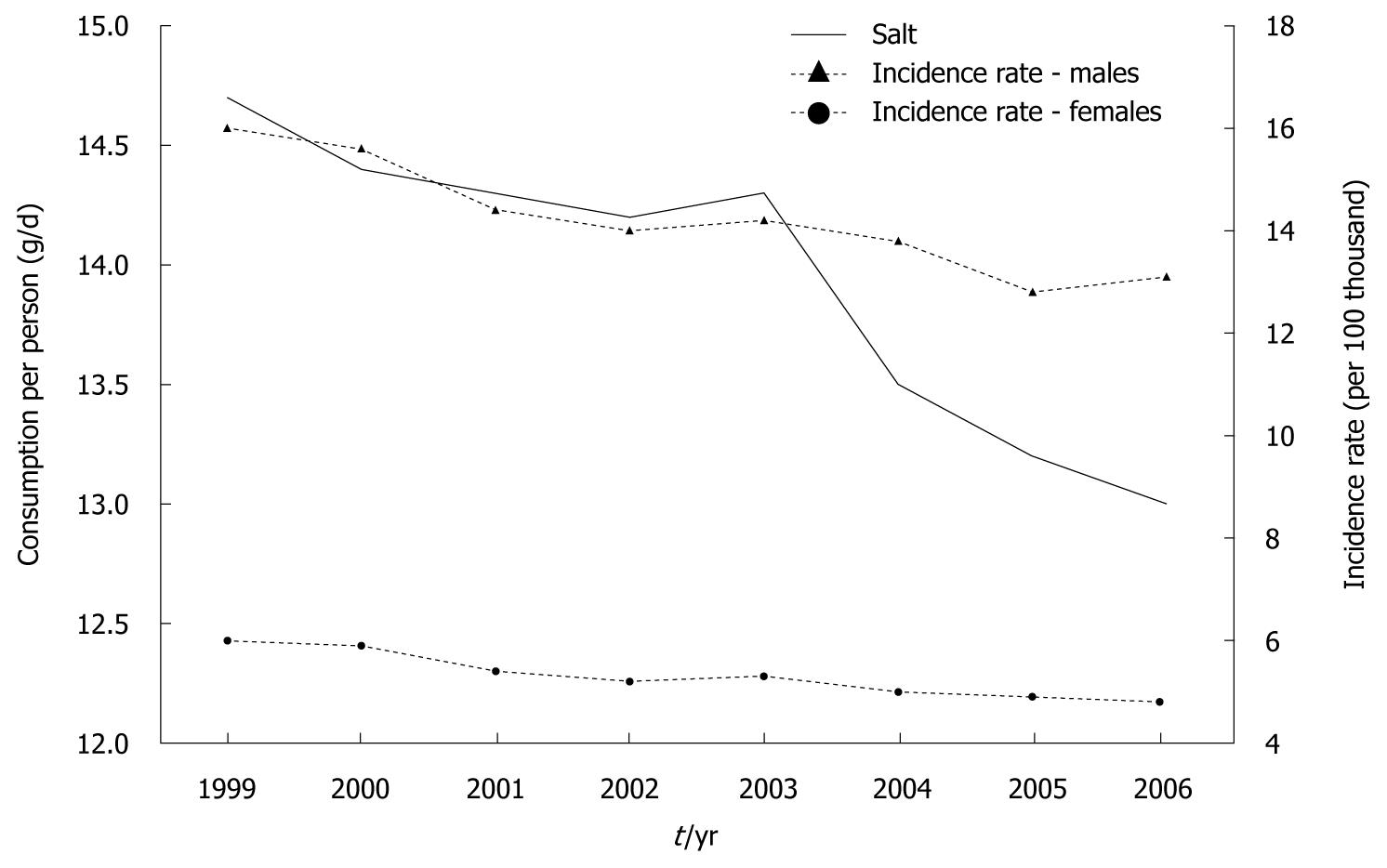

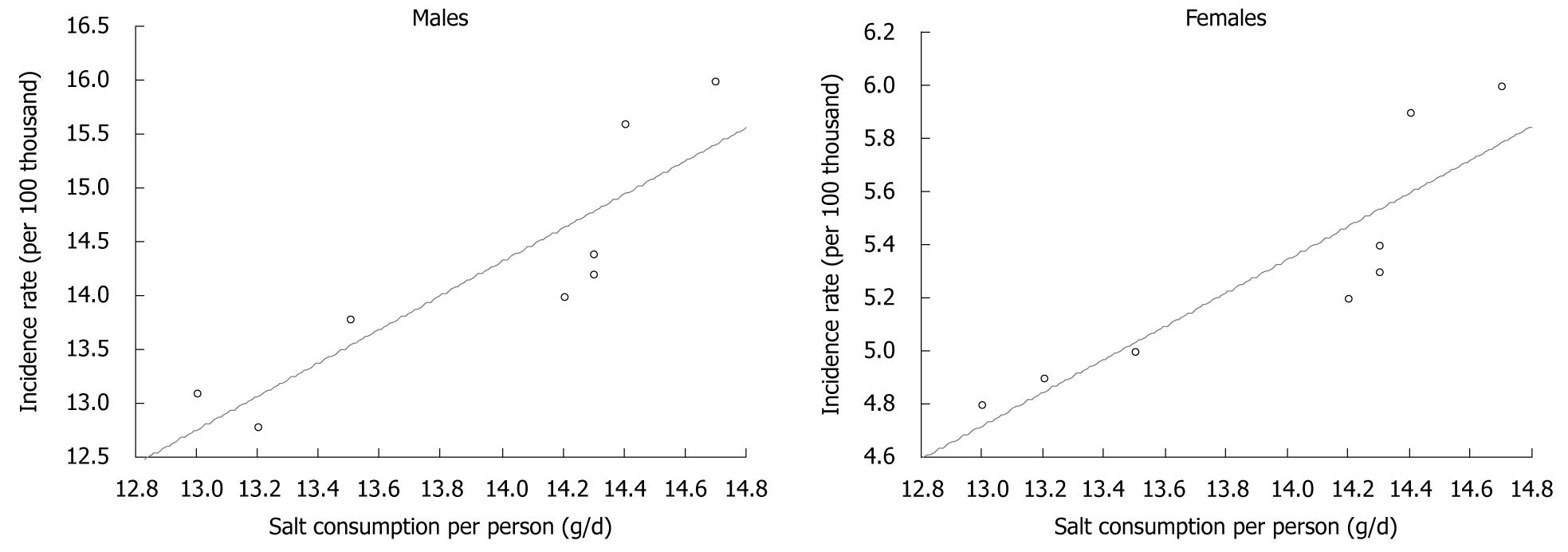

Data on total sodium chloride consumption, including both table salt and salt contained in food products (calculated on the basis of sodium content) showed that between 1999 and 2006, this consumption decreased significantly (Figure 9). At the same time, similar to previous years, a regular decrease in gastric cancer morbidity has been recorded, both for men and women. Calculations made for the purposes of this study demonstrated almost full correlation between the analyzed factors (Figure 10).

Our results enabled us to conclude that dietary factors have had a significant impact on gastric cancer risk in Poland. Their importance was underlined by the very high decrease in gastric cancer morbidity rate within the past few decades, despite a significant prevalence of H. pylori infection (73% of total population and 85-95% of adults aged > 25 years)[6] and smoking, which are important, commonly accepted factors that increase gastric cancer risk.

Infection with H. pylori (first-class carcinogen) is considered to be an essential factor for initiation of a series of inflammatory lesions in gastric mucous membrane, from chronic superficial inflammation to pre-cancer lesions (atrophic inflammation, metaplasia, dysplasia), from which gastric cancer may develop[18,19]. Gastric cancer grows as a result of complex interactions between genetic factors, virulence of H. pylori and environmental factors (dietary pattern, smoking). Our study shows that nutritional factors probably constitute one of the most important elements in these complex interactions.

For many years vitamin C has been considered as a significant factor for decreasing the risk of gastric cancer morbidity. As some studies have demonstrated, high concentrations of this vitamin in gastric juice and gastric mucous membrane can establish unfavorable conditions for development of H. pylori in the stomach, and its administration in high doses can even lead to eradication of this bacterium[20]. It has been proven that vitamin C reduces growth of bacteria in culture, and the activity of urease produced by these bacteria[21]. This enzyme enables H. pylori to survive in the acid environment of gastric juice, because it alkalizes the microenvironment by decomposition of urea to ammonium and carbon dioxide. However, it should be emphasized that the most important mechanism by which vitamin C can reduce the carcinogenic effect of H. pylori infection is destruction of free oxygen radicals that are produced in great amounts during infection[22]. They damage the genetic material of gastric epithelial cells, which leads to mutations.

It can be assumed that increased vitamin C intake reduces the deficiency in vitamin C in smokers. Smoking, similar to H. pylori infection, results in lower concentration of vitamin C in gastric juice. This decrease is greater in smokers infected with H. pylori compared with non-smokers[21]. An increase in consumption of fruit, vegetables and fruit juices could reduce the risk of gastric cancer development in smokers.

The impact of vitamin C on the decreased concentration of N-nitro compounds in the stomach in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis might also be significant[23,24]. A previous study has proven that vitamin C has the ability to slow down the nitrosation process, which results in the presence of nitrosamines in the stomach; compounds that have a mutagenic effect and are considered as carcinogens[25]. In vitro and in vivo tests have shown that ascorbic acid is the strongest inhibitor of this process[26]. It reacts with nitrites to produce nitrogen oxides. It oxidizes itself to dehydroascorbic acid, which reduces the nitrosation reaction; details of which remain unknown. In addition, ascorbic acid reduces transformation of nitrates to nitrites, which are direct substrates for nitrosamine production. The above is of significant importance in H. pylori infection, because, in the course of such infection, there is a significant increase in the concentration of nitrous compounds that are the source for nitrosamine production.

We found a very high correlation between decrease in gastric cancer morbidity and increase in dietary vitamin C content, which was related to growing consumption of fruit and vegetables. The purpose of many studies has been to examine the association between fruit and vegetable consumption and the incidence of gastric cancer. In a prospective study of Swedish women and men, consumption of vegetables was inversely associated with risk of gastric cancer after controlling for potential confounders[27]. However, no significant association was observed between fruit consumption and gastric cancer risk. In a Canadian study that evaluated associations between dietary patterns and incident gastric cancer risk, dietary patterns characterized by increased consumption of fruit and vegetables were associated with lower risk[28]. The association between vegetables and fruit consumption and gastric cancer risk was investigated in the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study[29]. That study suggested that vegetable and fruit intake, even in low amounts, was associated with a lower risk of stomach cancer. In contrast, a different Japanese study (Japan Collaborative Cohort Study) found no association between stomach cancer mortality and consumption of fruit and vegetables[30]. The Netherlands Cohort Study found evidence for an inverse association between stomach cancer and the consumption of vegetables and fruit, however, it became weaker and non-significant in multivariate analysis[31].

The nested case-control EPIC study is one of the largest prospective analyses of the association of nutrition with cancer. That study found no association between total vegetable intake or specific groups of vegetables and gastric cancer risk, except for the intestinal type, for which a negative association was found for total vegetable intake. There was no evidence of any association between fresh fruit intake and gastric cancer risk[32]. Within the EPIC cohort, dietary vitamin C also showed no significant association with gastric cancer risk at any level of intake[33].

In Poland, decreased salt consumption within the past few decades has probably also contributed to the decrease in gastric cancer morbidity. High concentrations of sodium chloride in the stomach facilitate damage and inflammation of mucous membranes, which leads to development of atrophic lesions, which are pre-cancerous lesions[34]. A high-salt diet is considered to alter the viscosity of the protective mucous barrier and facilitate exposure to carcinogenic factors such as nitrates. Some information suggests that high salt intake in some way facilitates colonization with H. pylori[35,36]. However, other studies have suggested that high salt intake per se does not promote H. pylori infection[37].

According to the WCRF/AICR report, any effect of salt on stomach cancer is principally the result of regular consumption of salted or salt-preserved food, rather than salt as such[15]. Some studies have investigated only salt added in cooking or at the table, but this is usually a small proportion of total salt consumption. The results from such studies are liable to produce different conclusions. For example in the Netherlands Cohort Study, an inverse association was found between stomach cancer and salt added to hot meals[38].

However many studies have confirmed the association between salt and/or salty food intake and the risk of stomach cancer. In a case-control study in Lithuania, a higher risk of gastric cancer was found in subjects who added salt to prepared meals or those who liked salty food[39]. In a cohort study conducted in a rural area of Japan, the frequent intake of highly salted food remained as a significant risk factor for gastric cancer mortality[40].

It is not entirely clear whether high salt intake and H. pylori infection are independent or interdependent risk factors. In a prospective study of a Japanese population, the effect of high salt intake on gastric carcinogenesis was strong in subjects who had atrophic gastritis and H. pylori infection[37]. A study of 67 Chinese rural counties has suggested an interaction between high salt consumption and H. pylori infection[41]. The significant correlation between H. pylori prevalence and stomach cancer mortality was only observed in counties with high levels of urinary sodium, and the significant correlation between urinary sodium and stomach cancer mortality only existed in counties with high H. pylori prevalence. In a case-control study in Korea, subjects with positive H. pylori infection and a high salt preference had a 10-fold higher risk of early gastric cancer than those without H. pylori infection and a low salt preference[42].

In light of the above-mentioned results, the observed decrease in gastric cancer morbidity in Poland could be explained by the fact that, in the years when salt consumption was very high, the impact of H. pylori infection on carcinogenesis was significantly higher compared to the time in which dietary salt content was lower. Another factor that could have influenced the decrease in gastric cancer morbidity in Poland could be improvement in food storage, which has resulted from better equipment of households with refrigerators. This method of food storage protects fruit and vegetables against loss of vitamin C. It also prevents growth of microorganisms that can reduce nitrates contained in food products to nitrites.

The WCRF/AICR report has concluded that there is convincing evidence that use of refrigeration indirectly protects against gastric cancer[15]. Some surveys have shown a significant association between the use of refrigeration and reduced risk of gastric cancer. According to a case-control study conducted in Northern Italy, 5% of all gastric cancer cases were attributable to less than 30 years use of an electric refrigerator[16]. In a case-control study in Germany, the use of a refrigerator at home for ≥ 30 years compared to ≤ 24 years showed an inverse relationship with stomach cancer risk[17]. However, in the Netherlands Cohort Study, no association was observed for duration of refrigerator use[38]. Similarly, in a Polish case-control study, no association was found between stomach cancer risk and long-term refrigerator use[43].

To summarize, our study shows that the effect of certain nutritional factors (increase in fruit and vegetable consumption and related increase in dietary vitamin C and decrease in salt consumption) within the past few decades could have had a positive preventive impact on gastric cancer. The preventive effect probably depends on recognized and well-documented mechanisms reducing the risk of carcinogenesis, and perhaps on still unknown mechanisms. The prevention might also occur in populations that are exposed to other, strong, unfavorable environmental factors (carcinogens), such as H. pylori or smoking. Our results constitute a crucial argument for aiming to improve diet in the population through nutritional education, food production and mass catering.

In many countries, gastric cancer morbidity within the past few decades has reduced significantly. This phenomenon is most probably related to favorable changes in the dietary pattern in developed countries; mostly to increased consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables and decreased consumption of salt-preserved food. Lower gastric cancer morbidity is also related to lower prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, which is considered to be essential for development of the majority of gastric cancer cases. However, Poland seems to be a particular case. Despite the fact that the percentage of people infected with H. pylori is unusually high, in 2006, gastric cancer morbidity rate was twofold lower compared to that in 1960.

Gastric cancer ranks fourth in morbidity and second in mortality among malignant cancers worldwide. Despite the decline in incidence of this cancer, it is important to investigate the factors that could decrease or increase the risk of the disease. In this study, the relationship between diet and gastric cancer morbidity during the past few decades in Poland was evaluated.

The relationship between diet and cancer morbidity is mainly based on the results of case-control studies or prospective cohort studies. The present study was conducted using national data on diet that were derived from food balance sheets or household budget surveys.

The results suggest a positive influence of increased fruit and vegetable consumption, and related increase in dietary vitamin C content and reduced salt consumption, on the decline in gastric cancer morbidity. These results could be useful in preparation of dietary guidelines for cancer prevention.

Metaplasia is the reversible replacement of one differentiated cell type with another mature differentiated cell type. Dysplasia is an expansion of immature cells, with a decrease in the number and location of mature cells. Urease is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea into carbon dioxide and ammonia. Nitrosation is a process of converting organic compounds into nitroso derivatives.

The manuscript is well written and underlines in an exhaustive manner the cause of the decline in gastric cancer incidence in Poland.

Peer reviewer: Maria Gabriella Caruso, MD, Piazza Giuseppe Garibaldi 49, 70122 Bari, Italy

S- Editor Shi ZF L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Boyle P, Levin B. World Cancer Report 2008. World Health Organization. Lyon: IARC Press 2008; 344-349. |

| 2. | Coggon D, Barker DJ, Cole RB, Nelson M. Stomach cancer and food storage. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1178-1182. |

| 3. | La Vecchia C, Negri E, D'Avanzo B, Franceschi S. Electric refrigerator use and gastric cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:136-137. |

| 4. | Bruce MG, Maaroos HI. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2008;13 Suppl 1:1-6. |

| 5. | Mbulaiteye SM, Hisada M, El-Omar EM. Helicobacter Pylori associated global gastric cancer burden. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1490-1504. |

| 6. | Matysiak-Budnik T, Mégraud F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection with special reference to professional risk. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;48 Suppl 4:3-17. |

| 7. | Koszarowski T, Gadomska H, Wronkowski Z, Romejko M. Malignant carcinoma in Poland in years 1952-1982. Warsaw: Maria Skłodowska-Curie Memorial Cancer Center and Institute of Oncology 1987; . |

| 8. | Maria Skłodowska-Curie Memorial Cancer Center and Institute of Oncology. Reports based on data of National Cancer Registry. Available from: http://85.128.14.124/krn/english/index.asp. |

| 9. | Sekuła W, Figurska K, Jutrowska I, Barysz A. Changes in the food consumption pattern during the political and economic transition in Poland and their nutritional and health implications. Polish Popul Rev. 2005;27:141-158. |

| 10. | Sekuła W, Niedziałek Z, Figurska K, Morawska M, Boruc T. Food Consumption in Poland Converted into Energy and Nutrients, 1950-1995. Warsaw: National Food and Nutrition Institute 1996; . |

| 11. | Sekuła W. Political and economic determinants of dietary changes-focus on Poland. Żyw Człow Metab. 2001;28:146-159. |

| 12. | Kunachowicz H, Nadolna I, Przygoda B, Iwanow K. Tables of content and nutritional value of food. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL 2005; . |

| 13. | Central Statistical Office. Concise Statistical Yearbook 1939. Warsaw: Central Statistical Office 1939; . |

| 14. | Sekuła W, Ołtarzewski M, Barysz A. An estimate of the sodium chloride consumption in Poland based on the results of the households budget surveys. Żyw Człow Metab. 2008;35:265-282. |

| 15. | World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: WCRF/AICR 2007; . |

| 16. | La Vecchia C, D'Avanzo B, Negri E, Decarli A, Benichou J. Attributable risks for stomach cancer in northern Italy. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:748-752. |

| 17. | Boeing H, Frentzel-Beyme R, Berger M, Berndt V, Göres W, Körner M, Lohmeier R, Menarcher A, Männl HF, Meinhardt M. Case-control study on stomach cancer in Germany. Int J Cancer. 1991;47:858-864. |

| 18. | Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735-6740. |

| 19. | Lauwers GY. Defining the pathologic diagnosis of metaplasia, atrophy, dysplasia, and gastric adenocarcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:S37-S43; discussion S61-S62. |

| 20. | Jarosz M, Dzieniszewski J, Dabrowska-Ufniarz E, Wartanowicz M, Ziemlanski S, Reed PI. Effects of high dose vitamin C treatment on Helicobacter pylori infection and total vitamin C concentration in gastric juice. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1998;7:449-454. |

| 21. | Jarosz M, Dzieniszewski J, Dabrowska-Ufniarz E, Wartanowicz M, Ziemlanski S. Tobacco smoking and vitamin C concentration in gastric juice in healthy subjects and patients with Helicobacter pylori infection. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2000;9:423-428. |

| 22. | Davies GR, Simmonds NJ, Stevens TR, Sheaff MT, Banatvala N, Laurenson IF, Blake DR, Rampton DS. Helicobacter pylori stimulates antral mucosal reactive oxygen metabolite production in vivo. Gut. 1994;35:179-185. |

| 23. | Kyrtopoulos SA. Ascorbic acid and the formation of N-nitroso compounds: possible role of ascorbic acid in cancer prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:1344-1350. |

| 24. | Mirvish SS. Effects of vitamins C and E on N-nitroso compound formation, carcinogenesis, and cancer. Cancer. 1986;58:1842-1850. |

| 25. | Mirvish SS. Inhibition by vitamins C and E of in vivo nitrosation and vitamin C occurrence in the stomach. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1996;5 Suppl 1:131-136. |

| 26. | Mirvish SS. Blocking the formation of N-nitroso compounds with ascorbic acid in vitro and in vivo. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1975;258:175-180. |

| 27. | Larsson SC, Bergkvist L, Wolk A. Fruit and vegetable consumption and incidence of gastric cancer: a prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1998-2001. |

| 28. | Campbell PT, Sloan M, Kreiger N. Dietary patterns and risk of incident gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:295-304. |

| 29. | Kobayashi M, Tsubono Y, Sasazuki S, Sasaki S, Tsugane S. Vegetables, fruit and risk of gastric cancer in Japan: a 10-year follow-up of the JPHC Study Cohort I. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:39-44. |

| 30. | Tokui N, Yoshimura T, Fujino Y, Mizoue T, Hoshiyama Y, Yatsuya H, Sakata K, Kondo T, Kikuchi S, Toyoshima H. Dietary habits and stomach cancer risk in the JACC Study. J Epidemiol. 2005;15 Suppl 2:S98-S108. |

| 31. | Botterweck AA, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA. A prospective cohort study on vegetable and fruit consumption and stomach cancer risk in The Netherlands. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:842-853. |

| 32. | González CA, Pera G, Agudo A, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Ceroti M, Boeing H, Schulz M, Del Giudice G, Plebani M, Carneiro F. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of stomach and oesophagus adenocarcinoma in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-EURGAST). Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2559-2566. |

| 33. | Jenab M, Riboli E, Ferrari P, Sabate J, Slimani N, Norat T, Friesen M, Tjønneland A, Olsen A, Overvad K. Plasma and dietary vitamin C levels and risk of gastric cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-EURGAST). Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:2250-2257. |

| 34. | Kono S, Hirohata T. Nutrition and stomach cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1996;7:41-55. |

| 35. | Fox JG, Dangler CA, Taylor NS, King A, Koh TJ, Wang TC. High-salt diet induces gastric epithelial hyperplasia and parietal cell loss, and enhances Helicobacter pylori colonization in C57BL/6 mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4823-4828. |

| 36. | Beevers DG, Lip GY, Blann AD. Salt intake and Helicobacter pylori infection. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1475-1477. |

| 37. | Shikata K, Kiyohara Y, Kubo M, Yonemoto K, Ninomiya T, Shirota T, Tanizaki Y, Doi Y, Tanaka K, Oishi Y. A prospective study of dietary salt intake and gastric cancer incidence in a defined Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:196-201. |

| 38. | van den Brandt PA, Botterweck AA, Goldbohm RA. Salt intake, cured meat consumption, refrigerator use and stomach cancer incidence: a prospective cohort study (Netherlands). Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:427-438. |

| 39. | Strumylaite L, Zickute J, Dudzevicius J, Dregval L. Salt-preserved foods and risk of gastric cancer. Medicina (Kaunas). 2006;42:164-170. |

| 40. | Kurosawa M, Kikuchi S, Xu J, Inaba Y. Highly salted food and mountain herbs elevate the risk for stomach cancer death in a rural area of Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1681-1686. |

| 41. | Wang X, Terry P, Yan H. Stomach cancer in 67 Chinese counties: evidence of interaction between salt consumption and helicobacter pylori infection. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17:644-650. |

| 42. | Lee SA, Kang D, Shim KN, Choe JW, Hong WS, Choi H. Effect of diet and Helicobacter pylori infection to the risk of early gastric cancer. J Epidemiol. 2003;13:162-168. |

| 43. | Jedrychowski W, Boeing H, Popiela T, Wahrendorf J, Tobiasz-Adamczyk B, Kulig J. Dietary practices in households as risk factors for stomach cancer: a familial study in Poland. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1992;1:297-304. |