INTRODUCTION

Hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) of chemotherapy is a treatment option in cases of liver-confined metastatic disease from colorectal carcinoma and results in increased local drug concentrations. Although a recent meta-analysis involving 1277 patients[1] reported no significant survival benefit of fluoropyrimidine-based HAI in patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer, the study suggested using novel anticancer agents and/or drug combinations to improve the efficacy of HAI in the future. There is growing evidence for using the combination of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in different types of malignancies including colorectal cancer.

Here we present a case of radiological complete response after HAI of gemcitabine-oxaliplatin for a large unresectable liver metastasis from a colon cancer.

CASE REPORT

In April 2005, a 61-year-old man was referred to our hospital with rectal bleeding. A coloscopy revealed a subocclusive sigmoid mass 26 cm from the anal margin. A computed tomography (CT) scan performed before surgery revealed one liver metastasis that involved hepatic segment VIII. Carcinoembryonic antigen was not a tumor marker for this patient. The patient underwent sigmoid resection. Pathological examination revealed a sigmoid adenocarcinoma with 7 metastatic regional lymph nodes (pT3 pN2 M1). The patient received 10 cycles of the FOLFOX regimen (fluorouracil + oxaliplatin). The disease was stabilized according to RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours). The patient then underwent segmentectomy of hepatic segment VIII in November 2005. In January 2007, the patient presented with 5 new liver metastases that involved hepatic segments IV and VII. The patient received 12 cycles of the FOLFIRI (fluorouracil + irinotecan) and bevacizumab regimen. A partial response was obtained according to RECIST though the 5 metastases were still present on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The patient underwent right hepatectomy with partial resection of hepatic segment IV. This resection was complicated by serious liver failure, from which the patient eventually recovered.

In June 2008, the patient presented with a new liver metastasis measuring 4 cm in diameter. Molecular analysis of the tumor revealed no K-Ras mutation and no B-Raf mutation. The patient was treated with 6 cycles of FOLFIRI + cetuximab. However, in October 2008 the metastasis had progressed and measured 5 cm on the liver MRI (Figure 1). A repeat hepatic resection was contraindicated given the history of serious liver failure and the close proximity of the metastasis to the left portal vein. Therefore, HAI was proposed.

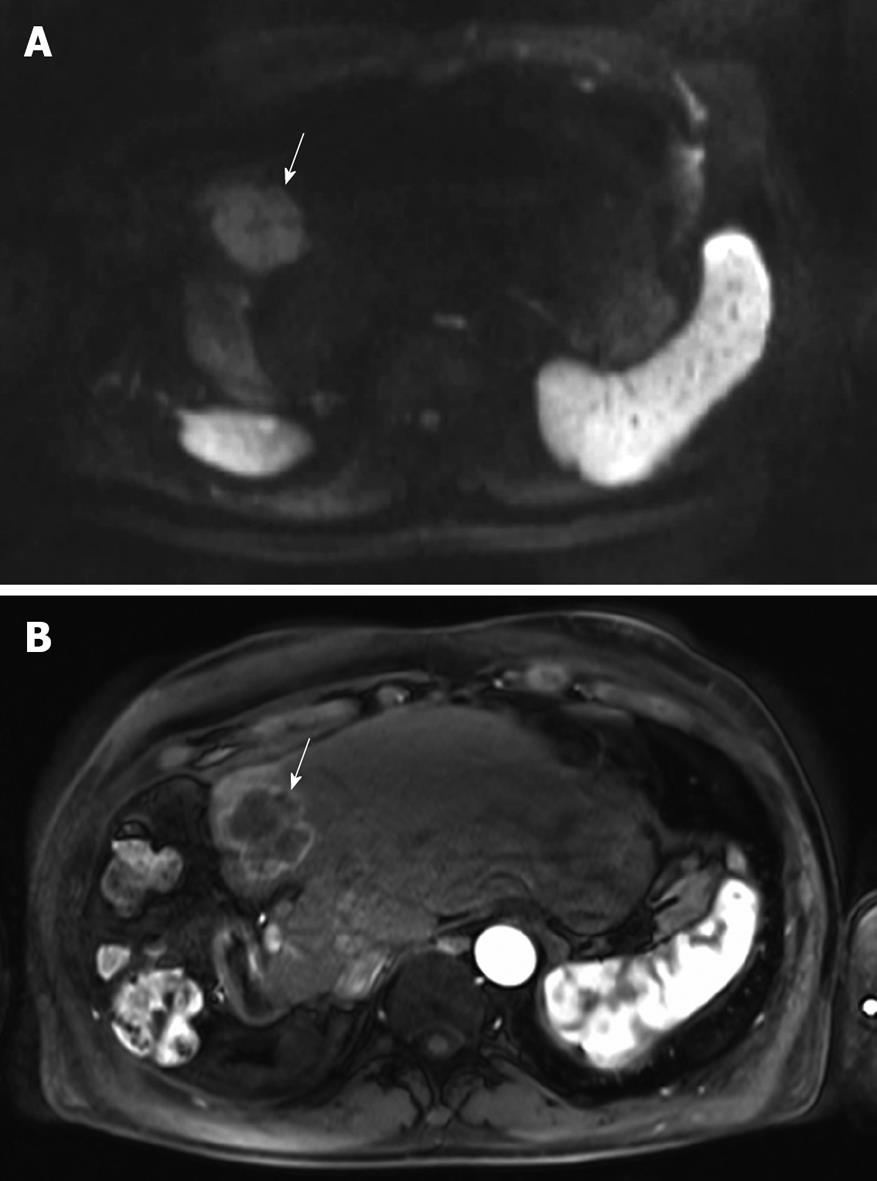

Figure 1 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver before starting hepatic arterial infusion (HAI).

A: The hyperintensity of the solitary large (5 cm) metastasis in segment 4 (arrow) on the axial diffusion-weighted image is consistent with malignancy; B: The metastasis is hypervascular (arrow) on the arterial phase after injection of gadolinium chelate.

An intrahepatic arterial catheter was percutaneously implanted after hepatic arteriography performed by femoral puncture. The catheter was then connected to a subcutaneous implantable port system, located in the inguinal area. After implantation, CT arteriography and a dynamic contrast-enhanced CT (DCE-CT) scan with injection of 1 mL/s of iodine contrast material (350 mg/mL) through the port were performed to check the absence of misperfusion and to assess tumor perfusion before starting hepatic arterial chemotherapy (Figure 2).

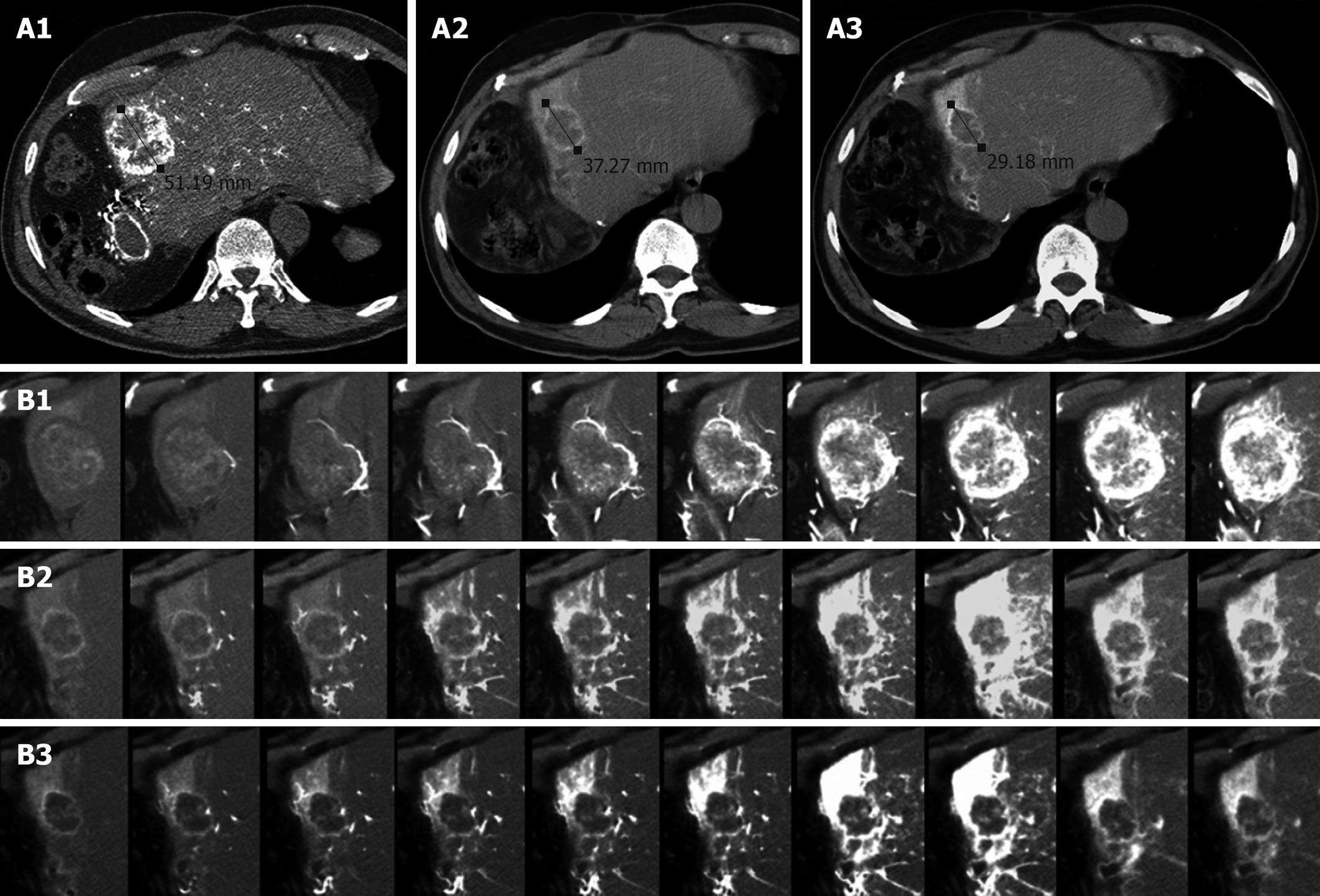

Figure 2 Computed tomography (CT) of liver metastasis.

A: CT arteriography at baseline (A1), after 2 cycles (A2) and after 6 cycles (A3) of HAI. The metastasis was hypervascular at baseline. It became shorter after 2 cycles but remained as a stable disease according to RECIST. After 6 cycles, a partial response was observed (43% reduction in diameter); B: Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT (DCE-CT) scan at baseline (B1), after 2 cycles (B2) and after 6 cycles (B3). At baseline, the tumor was progressively and massively enhanced. After 2 cycles, there was a dramatic decrease in tumor perfusion, strongly suggesting the efficacy of HAI. Normal hepatic segment 4 is strongly enhanced. After 6 cycles, only small enhanced areas are visible within the residual tumor.

The patient received 2 cycles of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (1 h infusion of gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 followed by 1 h infusion of oxaliplatin 100 mg/m2) every 2 wk. Evaluation by CT arteriography and DCE-CT scan (Figure 2) showed a stable disease according to RECIST, but a dramatic decrease in tumor perfusion. Therefore, the patient received 4 additional cycles. Imaging examinations revealed a partial response (residual tumor diameter: 2.5 cm) as well as an almost complete disappearance of tumor vascularity (Figure 2). After 2 more cycles of arterial chemotherapy, a liver MRI (Figure 3) showed the absence of tumor hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted imaging and a complete response regarding tumor perfusion. Positron emission tomography-CT with no significant hepatic uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose confirmed the absence of a viable macroscopic tumor. Finally, the treatment was completed with radiofrequency ablation of the residual mass. Only mild toxicity was observed, with grade 2 thrombocytopenia and asthenia with no specific toxicity related to the intraarterial procedure. To date, the patient is still in complete remission.

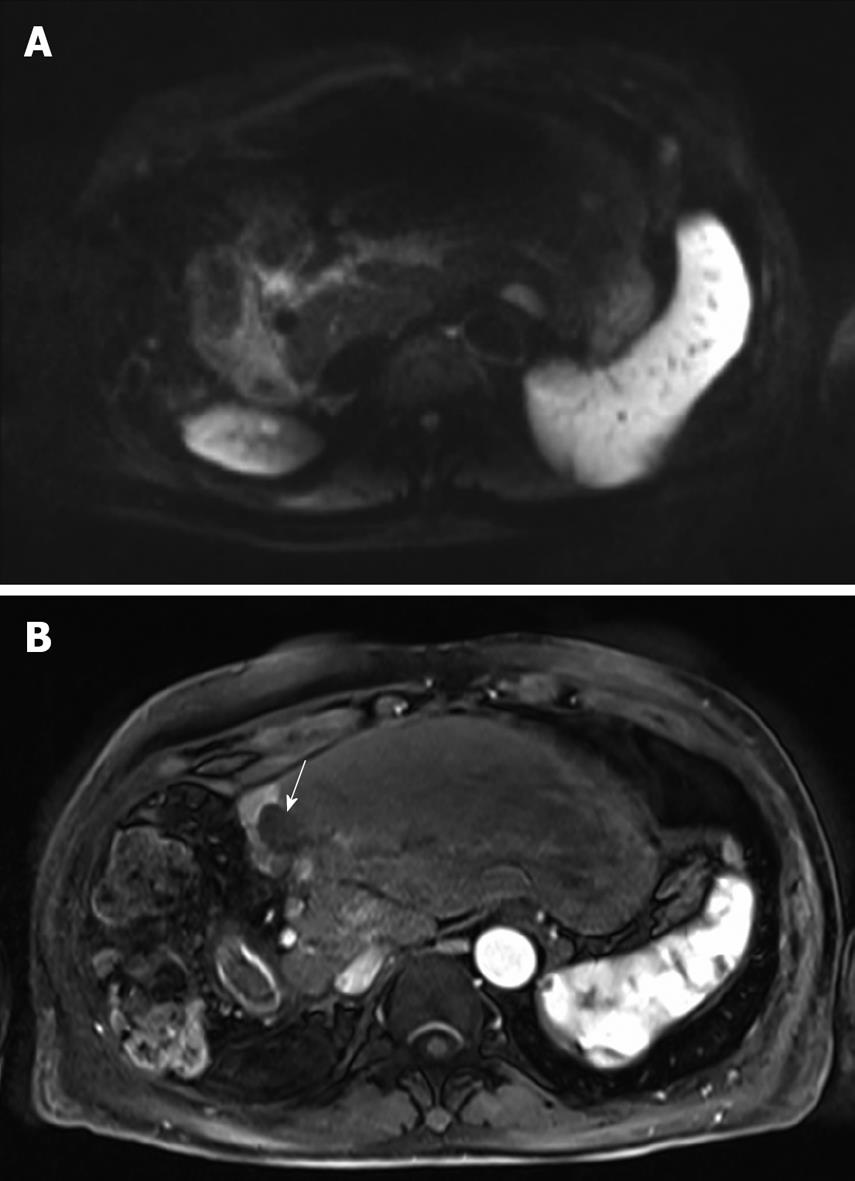

Figure 3 MRI of the liver after 8 cycles of HAI.

A: The lesion is isointense to the liver parenchyma on the diffusion-weighted image thereby suggesting the absence of viable tumor; B: The lesion is completely avascular (arrow) during the arterial phase after injection of gadolinium chelate. Note the enhancement of the remnant segment 4.

DISCUSSION

HAI of chemotherapy was first described in the early 1960s[2] and can be proposed in cases of liver-confined metastatic disease. It results in increased local drug concentrations and lower systemic concentrations and hence less toxicity than intravenous administration, provided that the drug is eliminated by hepatic extraction[3]. The use of HAI is also supported by the fact that, once hepatic metastases grow above 2-3 mm in size, they derive their blood supply from the hepatic artery, while normal hepatocytes are perfused mostly from portal circulation[4]. Although a recent meta-analysis involving 1277 patients[1] reported no significant survival benefit of fluoropyrimidine-based HAI in patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer, the study suggested using novel anticancer agents and/or drug combinations to improve the efficacy of HAI in the future. One of the major drawbacks of fluoropyrimidine-based HAI is the prolonged infusion time, which, in addition to causing patient discomfort, is likely to be responsible for chronic hepatobiliary toxicity[1,5].

To our knowledge, this is the first case to report the combined use of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin for HAI. The addition of oxaliplatin in systemic chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer has resulted in a higher response rate and longer survival than with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin[6]. HAI of oxaliplatin in a rabbit VX2 tumor model showed that the drug accumulated in the liver metastases in a 4:3 ratio (tumor/normal liver)[7]. A high liver extraction ratio has been reported with oxaliplatin administered in HAI[8], thereby explaining its low systemic bioavailability and thus, the good tolerance[9]. Human phase I or I/II studies reported a dose-limiting toxicity between 150 mg/m2 and 175 mg/m2 of oxaliplatin for every 3-wk administration via HAI[10,11]. The 100 mg/m2 dose used in our patient was well tolerated and resulted in no specific toxicity. However, since firstly oxaliplatin as a single agent has demonstrated only moderate activity in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer[12] and secondly, its combination with fluoropyrimidines would necessitate prolonged infusion with subsequent hepatobiliary toxicity, we needed to use a combination of oxaliplatin with another chemotherapeutic agent.

Gemcitabine is a deoxycytidine analogue which has to be intracellularly phosphorylated to its active forms (gemcitabine diphosphate and triphosphate) by deoxycytidine kinase[13], increased levels of which are found in liver metastases compared to normal liver tissue[14]. In addition, an in vitro study showed that gemcitabine had concentration- and time-dependent cytotoxic effects on many colon cancer cell lines[15]. As HAI makes it possible to reach an effective concentration locally, gemcitabine was deemed suitable for HAI. Interestingly, an experimental study conducted by Faivre et al[16] showed, in human colon cancer cell lines, a supra-additive effect of gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin, as well as a stronger effect of gemcitabine followed by oxaliplatin than the inverse. In a phase I study by Vogl et al[17], a maximum-tolerated dose of 1400 mg/m2 gemcitabine was reached after weekly 20-min HAIs of the drug in patients with cholangiocarcinomas and liver metastases from pancreatic cancer. A recent phase I study reported that gemcitabine given at doses higher or longer than the recommended systemic dose of 1000 mg/m2 over 30 min was well tolerated. All these results are consistent with the excellent tolerance in our patient.

CT arteriography using the implantable port system is useful to detect misperfusion[18] which may be responsible for undertreatment of liver metastases and/or for inadvertent chemotherapy perfusion of extra-hepatic organs such as the gastroduodenal wall. Early endovascular management prevents gastroduodenal lesions caused by the toxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs and allows treatment by HAI to be continued[19]. In this case, visual assessment of tumor perfusion on DCE-CT helped us to detect an early response to HAI. Although optimum quantitative perfusion parameters have not yet been determined, visual analysis of DCE-CT may be useful for monitoring the effects of HAI over time.

In conclusion, despite the poor prognosis of colon cancer with synchronous liver metastases, this patient has survived for 52 mo and is to date disease-free. This suggests that further trials involving HAI of oxaliplatin and gemcitabine in metastatic colon cancer are required.