Published online Mar 7, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i9.1110

Revised: January 4, 2010

Accepted: January 11, 2010

Published online: March 7, 2010

AIM: To examine the feasibility of predicting the flare-up of ulcerative colitis (UC) before symptoms emerge using the immunochemical fecal occult blood test (I-FOBT).

METHODS: We prospectively measured fecal hemoglobin concentrations in 78 UC patients using the I-FOBT every 1 or 2 mo.

RESULTS: During a 20 mo-period, 823 fecal samples from 78 patients were submitted. The median concentration of fecal hemoglobin was 41 ng/mL (range: 0-392 500 ng/mL). There were three types of patients with regard to the correlation between I-FOBT and patient symptoms; the synchronous transition type with symptoms (44 patients), the unrelated type with symptoms (19 patients), and the flare-up predictive type (15 patients). In patients with the flare-up predictive type, the values of I-FOBT were generally low during the study period with stable symptoms. Two to four weeks before the flare-up of symptoms, the I-FOBT values were high. Thus, in these patients, I-FOBT could predict the flare-up before symptoms emerged.

CONCLUSION: Flare-up could be predicted by I-FOBT in approximately 20% of UC patients. These results warrant periodical I-FOBT in UC patients.

- Citation: Kuriyama M, Kato J, Takemoto K, Hiraoka S, Okada H, Yamamoto K. Prediction of flare-ups of ulcerative colitis using quantitative immunochemical fecal occult blood test. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(9): 1110-1114

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i9/1110.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i9.1110

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic intestinal disorder of unknown etiology with a typically relapsing course. Although many UC patients often relapse with flare-ups of symptoms such as diarrhea and bloody stools despite appropriate maintenance therapies, the prediction of flare-ups a few weeks or months before symptoms emerge is impossible. If we could recognize relapses in the early stage, i.e. during the asymptomatic phase, treatment of the relapse could be started in the early stage and might allow the patient to enter remission again more easily.

The fecal occult blood test (FOBT) is generally used as a screening method for colorectal cancer (CRC)[1,2]. In many countries, the guaiac-based manual test is mainly used and validated to decrease mortality due to CRC[3-5]. Recently, however, mainly in Japan, the test has developed into an immunochemical method with instruments for automatic measurement. Immunochemical FOBT (I-FOBT) has been reported to be more sensitive and specific for CRC detection than the guaiac-based test, and its effectiveness has also been accepted and widely used in Western countries[6-21].

In this study, therefore, we measured fecal hemoglobin concentrations in UC patients in remission using an I-FOBT instrument each time they visited our hospital for regular UC-related check-ups. The aim of our study was to examine the feasibility of the prediction and prophylaxis of UC relapse by comparing fecal hemoglobin concentrations and symptoms in UC patients.

Between April 2006 and November 2007, all UC patients who visited Okayama University Hospital were requested to prepare and bring fecal samples each visit. A total of 110 patients routinely came to our hospital every month or every 2 mo for determination of their disease status. Of these, a total of 78 patients with submitted fecal samples were analyzed in this study. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

The diagnosis of UC was based on conventional criteria[22]. Patients without a definite diagnosis of UC (e.g. indeterminate colitis) were excluded. The duration of disease was defined as the period between the time of onset and the first hospital visit during the study period.

Clinical relapse was defined as follows: active phase with worsening symptoms or emerging new symptoms that required treatment with newly prescribed or increasing doses of 5-aminosalicylic acid, salazosulfapyridine, corticosteroids, azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, tacrolimus or infliximab, including enemas or suppositories with such ingredients. The start of apheresis therapy (leukocytapheresis) was also defined as a clinical relapse.

Details of the method used for the fecal samplings were described previously[17-20]. Fecal samples were prepared on the morning of or the day before the visit days. Patients were asked to prepare a fecal sample from a stool specimen by using the collection kit provided by the manufacturer (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan). The I-FOBT sampling probe is inserted into an 8 cm × 2 cm test tube-shaped container. The patient inserts the probe into several different areas of the stool and then reinserts it firmly into the tube to seal it. The probe tip with the fecal sample is suspended in a standard volume of hemoglobin-stabilizing buffer.

Submitted stool samples were immediately processed and examined using the OC-SENSOR neo (Eiken Chemical). The OC-SENSOR neo is the further-developed and large-scale version of the OC-SENSOR μ, which was used in previous reports[17-20].

We assessed patient symptoms and disease activity using the partial Mayo score. Schroeder et al[23] developed the Mayo score in 1987, which comprises 4 items: stool frequency, rectal bleeding, findings of flexible proctosigmoidoscopy, and physician’s global assessment. Each response is graded on a four-point scale ranging from “0” to “3”. A score of zero means stool frequency is normal, no rectal bleeding is seen, findings of flexible proctosigmoidoscopy are normal if inactive disease is present, and physician’s global assessment is normal. The total worst score is 12 points. This Mayo score is in common use in many clinical trials, and has noninvasive versions: the partial Mayo score (which excludes the mucosal appearance item from the 4-item index). Total worst score of the partial Mayo score is 9 points.

The patients were classified into three types according to I-FOBT data: synchronous transition with symptoms, the unrelated type with symptoms, and the flare-up predictive type. We first determined the patients who had the flare-up predictive type (the third type). Those patients with an I-FOBT value which was high an average of 1 mo before the flare-up of symptoms were assigned to this type.

After determining the third type, the remaining patients were classified into the first or second type by univariate regression analysis using I-FOBT values and the patient’s partial Mayo scores. The first type (synchronous transition with symptoms): Univariate regression analyses appeared significant or produced a P value of < 0.20. The second type (unrelated type with symptoms): Univariate regression analyses produced a P value of ≥ 0.20.

Statistical analysis was conducted using the SAS® System for Windows, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Trends were assessed with the exact trend test to compare three discrete variables. Continuous variables were compared among the three patient groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Comparisons of continuous variables were performed using Mann-Whitney’s U test. The results were considered to be statistically significant when P values were less than 0.05. To determine the correlation between the value of I-FOBT and the partial Mayo score, a univariate regression analysis was performed.

A total of 78 patients were analyzed. These patients comprised 33 men and 45 women, with a median age of 40 years. The median disease duration was 9 years (range: 1-37 years). Of the 78 patients, 40 (51%) had pancolitis, 22 (28%) had left-sided colitis, and 16 (21%) had proctitis. During the study period, a total of 823 fecal samples were submitted by 78 patients, with a median of 10 samples submitted per patient. The frequency of submission of fecal samples was 0.74 times per month for each patient.

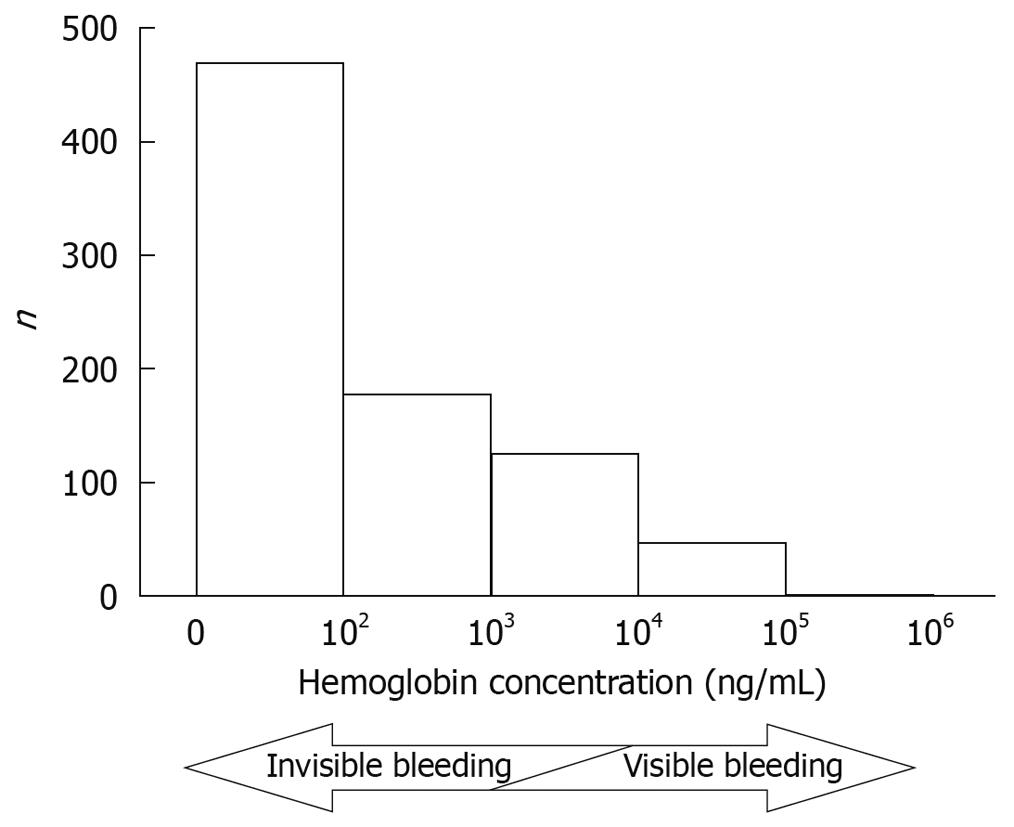

The quantified value of the I-FOBT for each fecal sample was immediately determined by the OC-SENSOR neo. The median concentration was 41 ng/mL (0-392 500 ng/mL), and the distribution of the 823 fecal samples is shown in Figure 1. In general, stools with hemoglobin concentrations of more than 1000-10 000 ng/mL were recognized as bloody stools.

We examined the correlation between the value of I-FOBT and the partial Mayo score in each patient by univariate regression analysis. We found three types of correlations between the two parameters: synchronous transition with symptoms, the unrelated type with symptoms, and the flare-up predictive type.

First type (synchronous transition with symptoms): In this type of patient, the values of I-FOBT were stable and did not fluctuate widely when patient symptoms were stable. However, the values increased or decreased along with deterioration or improvement of patient symptoms, respectively. These patients exhibited high I-FOBT values when their symptoms became worse. In turn, once their symptoms were relieved, the value of I-FOBT decreased. Forty-four patients (56%) were categorized into this type.

Second type (unrelated type with symptoms): The values of I-FOBT in this type of patient were not parallel with the symptoms. Of 78 patients, 19 (24%) were classified into this type. The values of I-FOBT in these patients were likely to be extremely high, although their symptoms were generally stable.

Third type (flare-up predictive type): In these patients, the values of I-FOBT were generally low during the period with stable symptoms. Before the flare-up of symptoms, the I-FOBT value was high, although the symptoms at that point had not worsened. An average of 1 mo after the rise in I-FOBT value (i.e. the day of the next consultation), the patient’s symptoms became worse, and additional UC therapies or admission was required. Therefore, the I-FOBT values in these patients could predict the worsening of symptoms nearly 1 mo in advance. Fifteen patients (19%) were classified in this type.

The demographic and clinical variables of the three types of patients are shown in Table 1. There was a higher proportion of females in the second-type group compared with the first- and third-type groups (P = 0.034). Age, disease duration, disease extent, and clinical course were not significantly different among the three groups. I-FOBT results were significantly higher in the second-type group compared with the first- and third-type groups (P < 0.0001).

| First type | Second type | Third type | P | |

| n | 44 | 19 | 15 | |

| Male/female | 23/21 | 3/16 | 7/8 | 0.034a |

| Age (yr) | 39 (18-79) | 40 (16-66) | 46 (27-70) | 0.54b |

| Disease duration (yr) | 9 (1-37) | 9 (1-28) | 8 (1-30) | 0.88b |

| Disease extent | ||||

| Pancolitis | 23 (52) | 8 (42) | 9 (60) | 0.22a |

| Left-side colitis | 10 (23) | 6 (32) | 6 (40) | |

| Proctitis | 11 (25) | 5 (26) | 0 (0) | |

| Total fecal samples | 427 | 204 | 192 | |

| Submitted fecal samples/person | 9 (4-20) | 10 (4-19) | 12 (6-26) | 0.13b |

| I-FOBT result (ng/mL)c | 9 (0-57 616) | 486 (0-142 639) | 189 (0-392 500) | < 0.0001b |

We were able to predict relapse before clinical symptoms emerged in approximately 20% of UC patients by quantifying fecal hemoglobin concentration on consultation days. The feasibility of predicting relapse is attractive, because it would permit earlier and therefore possibly more effective treatment. If colonoscopy is performed at the time when fecal hemoglobin concentration increases, but no symptoms of flare-up are observed, clinical relapse can be detected at the presymptomatic stage. If we start treatment for relapse at this stage, the severity of flare-ups could be reduced. Moreover, prophylaxis of flare-ups may be possible. Thus, follow up of the third-type of patients with I-FOBT would be beneficial.

Although many laboratory parameters (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP, platelet count, white blood cell count, α1-antitrypsin) have been proposed as predictors of clinical relapse in UC[24-31], it is difficult for these markers to predict relapse before symptoms emerge as they are not sufficiently specific or sensitive to inflammation in the colon. In contrast, increases in I-FOBT values are parallel with or predictive of the deterioration of symptoms in more than 80% of UC patients.

One promising predictive marker of relapse in UC is fecal calprotectin concentration. Tibble et al[32] and Costa et al[33] reported that in clinically quiescent UC patients followed for 12 mo, median fecal calprotectin levels at the beginning of the study in patients who relapsed were significantly higher than those in patients who did not relapse. In these reports, however, fecal calprotectin was measured once, and the concentration could be a marker of relapse that would occur several months after the measurement. Calprotectin is a granulocyte cytosolic protein, and a high fecal concentration of calprotectin indicates patients who are at risk of relapse. On the other hand, I-FOBT directly measures the fecal hemoglobin concentration, and a sequential change in fecal hemoglobin concentration could be a marker of relapse. Moreover, I-FOBT measurement was automated within a short time during outpatient consultation, and the instrument can be used as a screening method for CRC. Thus, sequential I-FOBT measurement is easier and more useful than the measurement of fecal calprotectin concentration in predicting early relapse.

There are limitations to this study. First, we adopted the 1-d method of I-FOBT. In CRC screening, the 2- or 3-d method is usually recommended because these methods are superior to the 1-d method in terms of sensitivity for colorectal neoplasia[34-36]. Therefore, in the present UC study the examination of two or three samples of feces in one consultation day may be more reliable. Second, I-FOBT can not be used in women during menstruation as the value of fecal hemoglobin concentration may be inaccurate.

In conclusion, we prospectively followed-up UC patients with I-FOBT. In some patients, an increase in fecal hemoglobin concentration was a useful marker of early relapse. The potential for sequential measurement is also an advantage of follow-up with I-FOBT. To confirm the usefulness of I-FOBT in the follow-up of UC patients, comparative studies are needed between patients with and without I-FOBT submission.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic intestinal disorder of unknown etiology with a typically relapsing course. Although many UC patients often relapse despite appropriate maintenance therapies, the prediction of flare-ups a few weeks or months before symptoms emerge is impossible.

Many laboratory parameters (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP, platelet count, white blood cell count, α1-antitrypsin) have been proposed as predictors of clinical relapse of UC, but it is difficult for these markers to predict relapse before symptoms emerge as they are not sufficiently specific or sensitive to inflammation in the colon.

This is the first study to report the feasibility of prediction of UC relapse using the immunochemical fecal occult blood test (I-FOBT).

Starting treatment for relapse in the early stage may allow the patient to enter remission again more easily than if treatment is started after the symptoms of flare-up emerge. In addition, the prophylaxis of flare-ups by modulating the maintenance therapy to anticipate flare-ups by a few days or weeks may become possible.

FOBT is generally used as a screening method for colorectal cancer. Recently, mainly in Japan, the test has developed into an immunochemical method with instruments for automatic measurement.

This study aimed to predict flare up of UC by estimating hemoglobin at regular intervals using I-FOBT. The authors evaluated a total of 78 patients over a period of 20 mo.

Peer reviewer: Gopal Nath, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Microbiology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005, India

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Allison JE. Review article: faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1-10. |

| 2. | Ouyang DL, Chen JJ, Getzenberg RH, Schoen RE. Noninvasive testing for colorectal cancer: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1393-1403. |

| 3. | Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM, Ederer F. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1365-1371. |

| 4. | Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW, James PD, Mangham CM. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:1472-1477. |

| 5. | Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jørgensen OD, Søndergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348:1467-1471. |

| 6. | Rozen P, Knaani J, Samuel Z. Performance characteristics and comparison of two immunochemical and two guaiac fecal occult blood screening tests for colorectal neoplasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2064-2071. |

| 7. | Rozen P, Knaani J, Samuel Z. Comparative screening with a sensitive guaiac and specific immunochemical occult blood test in an endoscopic study. Cancer. 2000;89:46-52. |

| 8. | Young GP, St John DJ, Cole SR, Bielecki BE, Pizzey C, Sinatra MA, Polglase AL, Cadd B, Morcom J. Prescreening evaluation of a brush-based faecal immunochemical test for haemoglobin. J Med Screen. 2003;10:123-128. |

| 9. | Allison JE, Tekawa IS, Ransom LJ, Adrain AL. A comparison of fecal occult-blood tests for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:155-159. |

| 10. | Saito H, Soma Y, Nakajima M, Koeda J, Kawaguchi H, Kakizaki R, Chiba R, Aisawa T, Munakata A. A case-control study evaluating occult blood screening for colorectal cancer with hemoccult test and an immunochemical hemagglutination test. Oncol Rep. 2000;7:815-819. |

| 11. | Nakama H, Zhang B, Zhang X. Evaluation of the optimum cut-off point in immunochemical occult blood testing in screening for colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:398-401. |

| 12. | Wong WM, Lam SK, Cheung KL, Tong TS, Rozen P, Young GP, Chu KW, Ho J, Law WL, Tung HM. Evaluation of an automated immunochemical fecal occult blood test for colorectal neoplasia detection in a Chinese population. Cancer. 2003;97:2420-2424. |

| 13. | Nakama H, Fattah A, Zhang B, Uehara Y, Wang C. A comparative study of immunochemical fecal tests for detection of colorectal adenomatous polyps. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:386-389. |

| 14. | Allison JE, Sakoda LC, Levin TR, Tucker JP, Tekawa IS, Cuff T, Pauly MP, Shlager L, Palitz AM, Zhao WK. Screening for colorectal neoplasms with new fecal occult blood tests: update on performance characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1462-1470. |

| 15. | St John DJ, Young GP, Alexeyeff MA, Deacon MC, Cuthbertson AM, Macrae FA, Penfold JC. Evaluation of new occult blood tests for detection of colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1661-1668. |

| 16. | Greenberg PD, Bertario L, Gnauck R, Kronborg O, Hardcastle JD, Epstein MS, Sadowski D, Sudduth R, Zuckerman GR, Rockey DC. A prospective multicenter evaluation of new fecal occult blood tests in patients undergoing colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1331-1338. |

| 17. | Vilkin A, Rozen P, Levi Z, Waked A, Maoz E, Birkenfeld S, Niv Y. Performance characteristics and evaluation of an automated-developed and quantitative, immunochemical, fecal occult blood screening test. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2519-2525. |

| 18. | Rozen P, Waked A, Vilkin A, Levi Z, Niv Y. Evaluation of a desk top instrument for the automated development and immunochemical quantification of fecal occult blood. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:MT27-MT32. |

| 19. | Levi Z, Hazazi R, Rozen P, Vilkin A, Waked A, Niv Y. A quantitative immunochemical faecal occult blood test is more efficient for detecting significant colorectal neoplasia than a sensitive guaiac test. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1359-1364. |

| 20. | Levi Z, Rozen P, Hazazi R, Vilkin A, Waked A, Maoz E, Birkenfeld S, Leshno M, Niv Y. A quantitative immunochemical fecal occult blood test for colorectal neoplasia. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:244-255. |

| 21. | van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, van Oijen MG, Fockens P, van Krieken HH, Verbeek AL, Jansen JB, Dekker E. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:82-90. |

| 22. | Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:3-11. |

| 23. | Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625-1629. |

| 24. | Lauritsen K, Laursen LS, Bukhave K, Rask-Madsen J. Use of colonic eicosanoid concentrations as predictors of relapse in ulcerative colitis: double blind placebo controlled study on sulphasalazine maintenance treatment. Gut. 1988;29:1316-1321. |

| 25. | Kjeldsen J, Lauritsen K, De Muckadell OB. Serum concentrations of orosomucoid: improved decision-making for tapering prednisolone therapy in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:933-941. |

| 26. | Cronin CC, Shanahan F. Immunological tests to monitor inflammatory bowel disease--have they delivered yet? Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:295-297. |

| 27. | Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:448-454. |

| 28. | Suffredini AF, Fantuzzi G, Badolato R, Oppenheim JJ, O'Grady NP. New insights into the biology of the acute phase response. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:203-214. |

| 29. | Campbell CA, Walker-Smith JA, Hindocha P, Adinolfi M. Acute phase proteins in chronic inflammatory bowel disease in childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1982;1:193-200. |

| 31. | Pepys MB, Druguet M, Klass HJ, Dash AC, Mirjah DD, Petrie A. Immunological studies in inflammatory bowel disease. Ciba Found Symp. 1977;283-304. |

| 32. | Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Bridger S, Fagerhol MK, Bjarnason I. Surrogate markers of intestinal inflammation are predictive of relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:15-22. |

| 33. | Costa F, Mumolo MG, Ceccarelli L, Bellini M, Romano MR, Sterpi C, Ricchiuti A, Marchi S, Bottai M. Calprotectin is a stronger predictive marker of relapse in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2005;54:364-368. |

| 34. | Nakama H, Zhang B, Fattah AS. A cost-effective analysis of the optimum number of stool specimens collected for immunochemical occult blood screening for colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:647-650. |

| 35. | Wong BC, Wong WM, Cheung KL, Tong TS, Rozen P, Young GP, Chu KW, Ho J, Law WL, Tung HM. A sensitive guaiac faecal occult blood test is less useful than an immunochemical test for colorectal cancer screening in a Chinese population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:941-946. |

| 36. | Nakama H, Yamamoto M, Kamijo N, Li T, Wei N, Fattah AS, Zhang B. Colonoscopic evaluation of immunochemical fecal occult blood test for detection of colorectal neoplasia. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:228-231. |