Published online Feb 21, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i7.875

Revised: December 1, 2009

Accepted: December 8, 2009

Published online: February 21, 2010

AIM: To suggest a new cleansing score system for small bowel preparation and to evaluate its clinical efficacy.

METHODS: Twenty capsule endoscopy cases were reviewed and small bowel preparation was assessed with the new scoring system. For the assessment, two visual parameters were used: proportion of visualized mucosa and degree of obscuration. Representative frames from small bowel images were serially selected and scored at 5-min intervals. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was obtained to assess the reliability of the new scoring system. For efficacy evaluation and validation, scores of our new scoring system were compared with another previously reported cleansing grading system.

RESULTS: Concordance with the previous system, inter-observer agreement, and intra-patient agreement were excellent with ICC values of 0.82, 0.80, and 0.76, respectively. The intra-observer agreements at four-week intervals were also excellent. The cut-off value of adequate image quality was found to be 2.25.

CONCLUSION: Our new scoring system is simple, efficient, and can be considered to be applicable in clinical practice and research.

- Citation: Park SC, Keum B, Hyun JJ, Seo YS, Kim YS, Jeen YT, Chun HJ, Um SH, Kim CD, Ryu HS. A novel cleansing score system for capsule endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(7): 875-880

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i7/875.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i7.875

Capsule endoscopy (CE) was introduced as a method for investigating the full length of the small intestine[1-3]. However, there are limitations such as impaired visualization by air bubbles, food residue, bile, and blood clots. Unfortunately, current CE does not have functions which allow suctioning of fluid or washing the small bowel mucosa during the examination. Therefore, since some of the lesions can be overlooked and missed, adequate bowel cleansing is mandatory for a successful CE[4]. There have been many studies on the necessity and methods of bowel preparation for CE[1,5-8]. However, the benefits of bowel preparation prior to CE remain controversial and it is unclear which method is best.

One of the reasons for this controversy is that the current grading systems have not been standardized and therefore, a generally accepted grading system is not available. The presence of numerous grading systems has caused difficulties in comparing the results of studies on small bowel preparation prior to CE[4,9]. In addition, most of the previously reported grading systems are time-consuming, complicated, and difficult to apply in the clinical setting. The aim of this study is to suggest a new cleansing score system for small bowel preparation and to evaluate its clinical efficacy.

Twenty CE cases were reviewed according to the protocol by three examiners who had experience in interpreting more than 50 cases of CE. These examiners separately assessed small bowel cleanliness by using the grading system described below. The software program Rapid Reader 4 (Given Imaging Ltd, Yoqneam, Israel) was used to review and score the images.

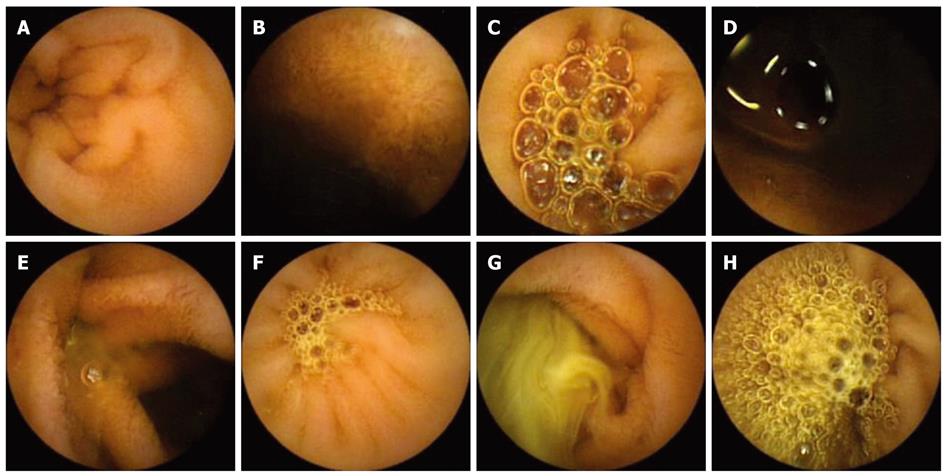

Two visual parameters were used in our scoring system. The first parameter was the proportion of visualized mucosa. This was scored using a 4-step scale ranging from 0 to 3: score 3, greater than 75%; score 2, 50% to 75%; score 1, 25% to 50%; score 0, less than 25% (Table 1, Figure 1). The second parameter was the degree of obscuration by bubbles, debris, and bile etc. This was also scored using a 4-step scale ranging from 0 to 3: score 3, less than 5%, no obscuration; score 2, mild (5% to 25%) obscuration; score 1, moderate (25% to 50%) obscuration; score 0, severe (greater than 50%) obscuration (Table 1, Figure 1). Images from the entire small bowel were serially selected at 5-min intervals (1 frame/5 min) by manual mode using the RAPID system. If the capsule got stuck or remained in the same place for more than 5 min, the frames were scored only once and not repeatedly.

| The proportion of visualized mucosa | |

| Score 3 | ≥ 75% |

| Score 2 | 50%-75% |

| Score 1 | 25%-50% |

| Score 0 | < 25% |

| The degree of bubbles, debris and bile | |

| Score 3 | < 5%, no obscuration |

| Score 2 | 5%-25%, mild obscuration |

| Score 1 | 25%-50%, moderate obscuration |

| Score 0 | ≥ 50%, severe obscuration |

Mean scores of each parameter were obtained by summing the scores of all selected images and dividing them by the number of examined frames. The representative values for each parameter were then calculated by the overall average of two mean scores.

First, 20 CE cases were reviewed and frames were selected twice: once according to our scoring system and once according to one of the previously reported systems which evaluated CE images for 2 min in every 5-min period (e.g. 240 frames/5 min or 40% of the small bowel images)[6]. The images from selected frames were then graded using the aforementioned parameters. The concordance of scores between the two grading systems was analyzed.

Second, the reliability of our grading system was evaluated by assessing the inter-observer, intra-patient, and intra-observer agreement. For the assessment on inter-observer agreement, three examiners each scored the same selected frames separately at 5-min intervals which were then compared. For the evaluation of intra-patient agreement, each examiner reviewed the same case after choosing their own starting frame within the first 5 min of the capsule’s entrance into the duodenum, from where the ensuing frames were picked up at 5-min intervals and scored accordingly. For the analysis on intra-observer agreement, the same frames from the same cases were scored once again after four weeks and scores were compared with the previous results.

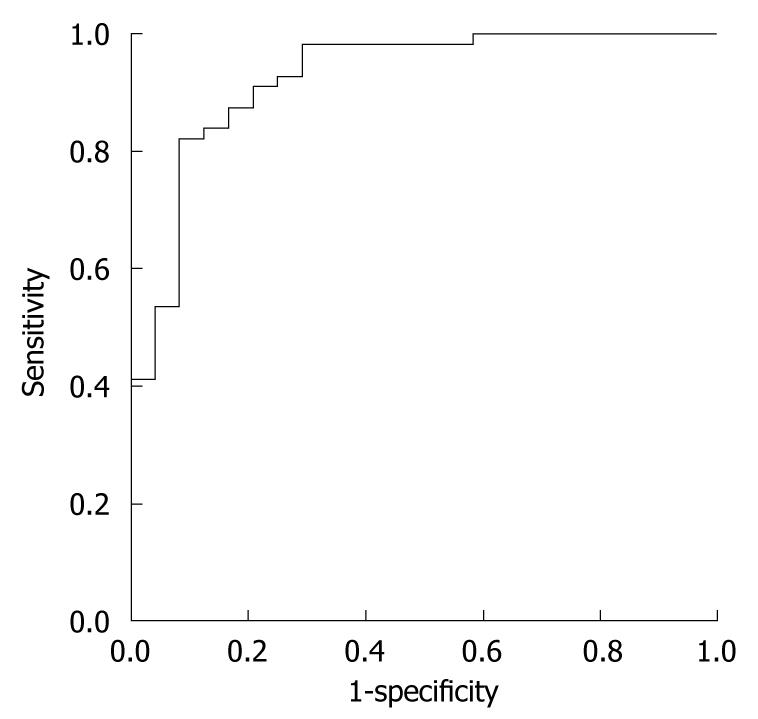

Third, in order to determine the cut-off value for adequate cleansing, our scoring system was compared with another grading system, which examined all of the images obtained from the entire small bowel. This grading system defined small bowel mucosa as “clean” if less than 25% of the mucosal surface was covered by intestinal contents or food debris, and cleanliness was graded as “adequate” if the time the mucosa appeared clean was greater than 90% of the total examination time[5]. Overall adequacy was compared with that of our scoring system and the results were analyzed using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

Concordance was determined by using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). An ICC value less than 0.40 was considered poor, between 0.40 and 0.75 was considered fair to good, and greater than 0.75 was considered excellent[6,10,11]. The cut-off value of the cleansing scores according to our scoring system, with optimal sensitivity and specificity, was determined using the ROC curve. Area under the curve (AUC) was used for assessing the overall accuracy of our scoring system which employed the ROC curve. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Twenty cases were selected from previously diagnosed patients. Mean age of the subjects was 48.5 (21-80) years and 80% (18/20) were male. Their indications for CE were gastrointestinal bleeding (12/20, 60%), iron deficiency anemia (4/20, 20%), abdominal pain (3/20, 15%), and diarrhea (1/20, 5%). Cases were prepared with 4 L of polyethylene glycol (PEG) four hours before examination without prokinetic agent or simethicone. The concordance between our cleansing score system and a previously reported system, which selected the frames and evaluated them for 2 min in every 5-min period, was excellent with an ICC value of 0.82 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.33-0.94, Table 2).

| Parameter | System | Score (median and IQR) | Inter-system ICC (95% CI) |

| Visualized mucosa | A | 2.44 (2.20-2.62) | 0.72 (0.27, 0.89) |

| B | 2.24 (2.11-2.48) | ||

| Degree of obscuration | A | 2.13 (1.92-2.35) | 0.86 (0.53, 0.95) |

| B | 1.98 (1.87-2.22) | ||

| Overall average | A | 2.30 (2.09-2.50) | 0.82 (0.33, 0.94) |

| B | 2.12 (1.97-2.36) |

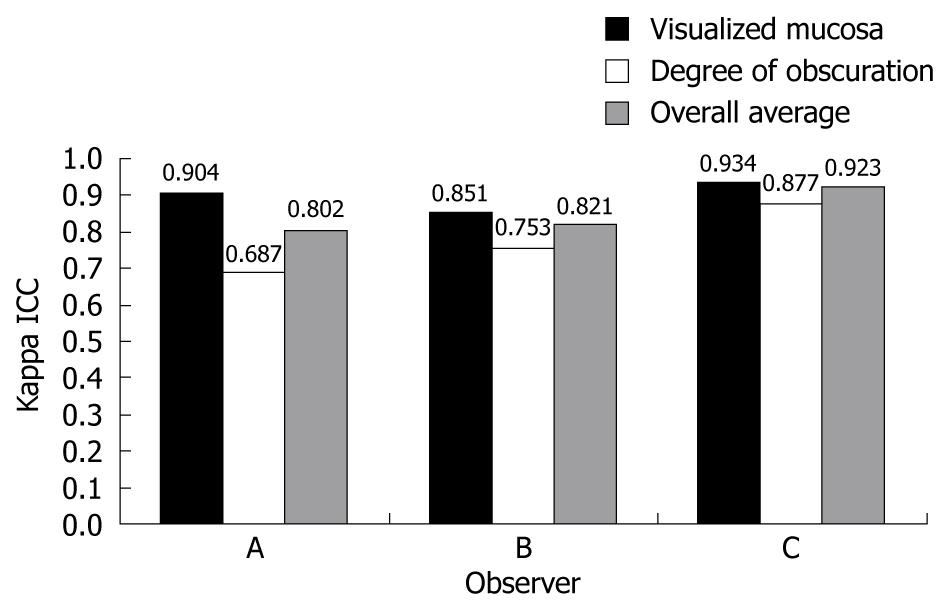

As for the assessment on reliability, inter-observer and intra-patient agreement were excellent with ICC values of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.35-0.93, Table 3) and 0.76 (95% CI: 0.41-0.93, Table 4), respectively. The data regarding the assessment on intra-observer agreement was available from three examiners and the results were also excellent with ICC values of 0.80, 0.82, and 0.92, respectively (Figure 2).

| Parameter | Observer | Score (median and IQR) | Inter-observer ICC (95% CI) |

| Visualized mucosa | A | 2.61 (2.40-2.81) | 0.88 (0.47, 0.99) |

| B | 2.62 (2.42-2.82) | ||

| C | 2.44 (2.20-2.62) | ||

| Degree of obscuration | A | 2.34 (2.17-2.55) | 0.71 (0.39, 0.87) |

| B | 2.28 (2.12-2.56) | ||

| C | 2.13 (1.92-2.35) | ||

| Overall average | A | 2.47 (2.32-2.63) | 0.80 (0.35, 0.93) |

| B | 2.47 (2.26-2.62) | ||

| C | 2.30 (2.09-2.50) |

| Parameter | Frame | Score (median and IQR) | Intra-patient ICC (95% CI) |

| Visualized mucosa | A | 2.33 (1.93-2.59) | 0.95 (0.81, 0.98) |

| B | 2.39 (1.88-2.66) | ||

| C | 2.31 (1.90-2.44) | ||

| Degree of obscuration | A | 2.13 (1.97-2.61) | 0.72 (0.39, 0.87) |

| B | 2.01 (1.52-2.34) | ||

| C | 2.01 (1.57-2.20) | ||

| Overall average | A | 2.28 (2.08-2.61) | 0.76 (0.41, 0.93) |

| B | 2.45 (1.70-2.50) | ||

| C | 2.16 (2.09-2.50) |

To assess the overall adequacy of small bowel cleansing, the ROC curve was generated to determine the cut-off value of image quality. The cut-off value, estimated by the ROC curve at an optimal level of sensitivity and specificity, was 2.25 with 85% sensitivity and 87% specificity. The AUC of the scoring system was 0.925 (95% CI: 0.859-0.990, Figure 3).

CE has provided a new perspective for diagnosing, treating, and monitoring small bowel diseases, such as obscure GI bleeding, Crohn’s disease, celiac sprue, polyposis syndromes, and small-bowel tumors.

However, CE has several limitations, one of which is image quality. Although 12 h-fasting or PEG ingestion is used for small bowel preparation in CE, air bubbles, intestinal secretions, bile or food residue occasionally cover the small bowel mucosa and obscure the view. The capsule endoscope is not equipped with functions to allow suctioning, inflating, and washing the lumen of the small intestine. Therefore, some parts of the lumen will not be visualized and examiners are unable to observe the entire small bowel mucosa thoroughly. This means that small bowel preparation plays an important role because it can improve image quality by cleansing the small bowel. There have been many studies on the preparation for CE, however, there is no standardized procedure for small bowel preparation for CE. In addition, preparation type, doses, and time of administration differ among centers.

To assess the effect of bowel preparation on the cleansing of the small bowel mucosa objectively, scoring systems for grading small bowel cleanliness have been introduced[1,5,6,12-14]. Prior studies on preparation, formulated and used their own scoring systems to grade small bowel cleanliness, thus making it difficult to compare the effect of preparation among studies[4,9]. For example, the grading system by Viazis et al[5] simply graded the small bowel cleanliness as “adequate” or “inadequate” and the time, during which the small bowel mucosa appeared unclean, was recorded using a timer; the concordance among the investigators was excellent (92.5%). However, thousands of frames per case had to be reviewed with this system. Therefore, grading the cleanliness is time-consuming and laborious. In the studies by Niv et al[1,7] the capsule images were graded according to the proportion of the small bowel transit time during which the intraluminal fluid interfered with visualization and interpretation. Although concordance on the quality of bowel preparation was excellent (kappa statistic = 0.91, P < 0.001), this grading system, in which the entire small bowel could be examined, is also time-consuming.

The study by Dai et al[13] assessed the visibility of the small bowel as a percentage of the visualized intestinal wall during 10-min video segments at 1-h intervals. In the study by Shiotani et al[6] individual frames were examined for 2 min of every 5-min period and scored using four visual parameters: circumference, bubbles, debris, and lightning. In recent studies, five video segments (each 5 or 10 min long) were selected from all the videos[15-17]. However, no standard guidelines for grading small bowel cleanliness are currently available. Most of the reported grading systems are time-consuming, complicated, and difficult to apply clinically. In addition, the reliability and efficacy of these grading systems have rarely been evaluated. Therefore, we designed a novel, simple, and time-sparing grading system of small bowel preparation for CE. In our scoring system, one frame was selected every 5 min (1 frame/5 min) to reduce the duration of grading small bowel cleansing. As a result, the duration of grading was greatly shortened compared with prior systems, which evaluated the entire small bowel mucosa. Our scoring system was compared with a previous method, which analyzed the frames for 2 min of every 5-min period; this method is a grading system that has recently been reported, but is time-consuming in that a substantial number of frames have to be analyzed. The concordance between this grading system and our scoring system was excellent.

Validity and reliability are two minimum qualities required for a grading system. Without reliability, even a valid scale can differ among study groups[18]. In a recent study, the quantitative index (QI) was better than the qualitative evaluation (QE) for intra-observer and inter-observer reliability[19]. To make the scoring system more reliable, we selected two parameters: the proportion of visualized mucosa and the degree of obscuration by bubbles, debris, bile, etc. For each parameter, small bowel cleanliness can be graded objectively by scoring the images according to the percent of the area. As a result, although the agreement on the degree of obscuration tended to be lower than that of the visualized mucosa in some cases, inter-observer, intra-patient, and intra-observer agreements were excellent. If the examiners in our study had received a calibration exercise before grading cleanliness, the concordance may have been better.

To determine whether our grading system was reasonable for assessing the adequacy of small bowel preparation, we compared our system with the grading system by Viazis et al[5], and the AUC of the ROC curve was 0.925. This means that our grading system had good discriminative power. From the ROC curve, we found that the cut-off value of image quality score on adequate bowel cleansing was 2.25, which was considered to have optimal sensitivity and specificity. Therefore, this value may be used as a criterion for determining the overall adequacy of small bowel preparation for CE.

In conclusion, our novel scoring system for CE was simple, objective, and efficient. It showed excellent inter-observer, intra-patient, and intra-observer agreement. In addition, a cut-off value for the adequacy of small bowel preparation was also proposed. Therefore, our scoring system may be useful in clinical practice and in studies determining the optimal small bowel cleansing method.

For successful capsule endoscopy (CE), adequate bowel cleansing is mandatory. However, the benefits of bowel preparation prior to CE remain controversial and it is unclear which method is best. One of the reasons for this controversy is that the current grading systems have not been standardized and a generally accepted grading system is not available.

Most of the reported grading systems are time-consuming, complicated, and difficult to apply clinically. In addition, the reliability and efficacy of these grading systems have rarely been evaluated. Therefore, the authors designed a novel, simple, and time-sparing grading system of small bowel preparation for CE. For assessment, two visual parameters were used: the proportion of visualized mucosa and degree of obscuration. Representative frames from small bowel images were serially selected and scored at 5-min intervals. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was obtained to assess the reliability of the new scoring system. For efficacy evaluation and validation, scores of this new scoring system were compared with those of another previously reported cleansing grading system. Concordance with the previous system, inter-observer agreement, and intra-patient agreement were excellent with ICC values of 0.82, 0.80, and 0.76, respectively. The intra-observer agreements at four-week intervals were also excellent. The cut-off value for adequate image quality was shown to be 2.25.

In this scoring system, one frame was selected every 5 min (1 frame/5 min) to reduce the duration of grading small bowel cleansing. As a result, the duration of grading was greatly shortened compared with prior systems, which evaluated the entire small bowel mucosa. From the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, the found that the cut-off value of image quality score on adequate bowel cleansing was 2.25, which was considered to have optimal sensitivity and specificity. Therefore, this value may be used as a criterion to determine the overall adequacy of small bowel preparation for capsule endoscopy.

The new scoring system is simple, efficient, and may be useful in clinical practice and in studies to determine the optimal small bowel cleansing method.

ICC: A descriptive statistic that can be used when quantitative measurements are made on units that are organized into groups. It describes how strongly units in the same group resemble each other. Its major application is in the assessment of consistency or reproducibility of quantitative measurements made by different observers measuring the same quantity.

In this manuscript, authors have reported a novel cleansing score system for capsule endoscopy. This new scoring system is simple, and efficient. Furthermore, it showed good inter-observer, intra-patient, and intra-observer agreement.

Peer reviewers: Nageshwar D Reddy, Professor, Asian Institute of Gastroenterology, 6-3-652, Somajiguda, Hyderabad, 500082, India; Satoru Kakizaki, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine and Molecular Science, Gunma University, Graduate School of Medicine, 3-39-15 Showa-machi, Maebashi, Gunma, 371-8511, Japan

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Niv Y, Niv G, Wiser K, Demarco DC. Capsule endoscopy - comparison of two strategies of bowel preparation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:957-962. |

| 2. | Ell C, Remke S, May A, Helou L, Henrich R, Mayer G. The first prospective controlled trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2002;34:685-689. |

| 3. | Chong AK, Taylor A, Miller A, Hennessy O, Connell W, Desmond P. Capsule endoscopy vs. push enteroscopy and enteroclysis in suspected small-bowel Crohn's disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:255-261. |

| 4. | Villa F, Signorelli C, Rondonotti E, de Franchis R. Preparations and prokinetics. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2006;16:211-220. |

| 5. | Viazis N, Sgouros S, Papaxoinis K, Vlachogiannakos J, Bergele C, Sklavos P, Panani A, Avgerinos A. Bowel preparation increases the diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:534-538. |

| 6. | Shiotani A, Opekun AR, Graham DY. Visualization of the small intestine using capsule endoscopy in healthy subjects. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1019-1025. |

| 7. | Niv Y, Niv G. Capsule endoscopy: role of bowel preparation in successful visualization. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1005-1009. |

| 8. | Fireman Z, Paz D, Kopelman Y. Capsule endoscopy: improving transit time and image view. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5863-5866. |

| 9. | Ben-Soussan E, Savoye G, Antonietti M, Ramirez S, Ducrotté P, Lerebours E. Is a 2-liter PEG preparation useful before capsule endoscopy? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:381-384. |

| 10. | Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Epidemiology: beyond the basics. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers 2000; . |

| 11. | Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159-174. |

| 12. | Ge ZZ, Chen HY, Gao YJ, Hu YB, Xiao SD. The role of simeticone in small-bowel preparation for capsule endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2006;38:836-840. |

| 13. | Dai N, Gubler C, Hengstler P, Meyenberger C, Bauerfeind P. Improved capsule endoscopy after bowel preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:28-31. |

| 14. | Albert J, Göbel CM, Lesske J, Lotterer E, Nietsch H, Fleig WE. Simethicone for small bowel preparation for capsule endoscopy: a systematic, single-blinded, controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:487-491. |

| 15. | van Tuyl SA, den Ouden H, Stolk MF, Kuipers EJ. Optimal preparation for video capsule endoscopy: a prospective, randomized, single-blind study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1037-1040. |

| 16. | Lapalus MG, Ben Soussan E, Saurin JC, Favre O, D'Halluin PN, Coumaros D, Gaudric M, Fumex F, Antonietti M, Gaudin JL. Capsule endoscopy and bowel preparation with oral sodium phosphate: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:1091-1096. |

| 17. | Endo H, Kondo Y, Inamori M, Ohya TR, Yanagawa T, Asayama M, Hisatomi K, Teratani T, Yoneda M, Nakajima A. Ingesting 500 ml of polyethylene glycol solution during capsule endoscopy improves the image quality and completion rate to the cecum. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3201-3205. |

| 18. | Rostom A, Jolicoeur E. Validation of a new scale for the assessment of bowel preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:482-486. |

| 19. | Brotz C, Nandi N, Conn M, Daskalakis C, DiMarino M, Infantolino A, Katz LC, Schroeder T, Kastenberg D. A validation study of 3 grading systems to evaluate small-bowel cleansing for wireless capsule endoscopy: a quantitative index, a qualitative evaluation, and an overall adequacy assessment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:262-270, 270.e1. |