Published online Dec 7, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5739

Revised: July 10, 2010

Accepted: July 17, 2010

Published online: December 7, 2010

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of self expandable metallic stents (SEMS) in patients with malignant esophageal obstruction and fistulas.

METHODS: SEMS were implanted in the presence of fluoroscopic guidance in patients suffering from advanced and non-resectable esophageal, cardiac and invasive lung cancer between 2002 and 2009. All procedures were performed under conscious sedation. All patients had esophagus obstruction and/or fistula. In all patients who required reintervention, recurrence of dysphagia, hemorrhage, and fistula formation were indications for further endoscopy. Patients’ files were scanned retrospectively and the obtained data were analyzed using SPSS 13.0 for Windows. The χ2 test was used for categorical data and was analysis of variance for non-categorical data. Patients’ long-term survival was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

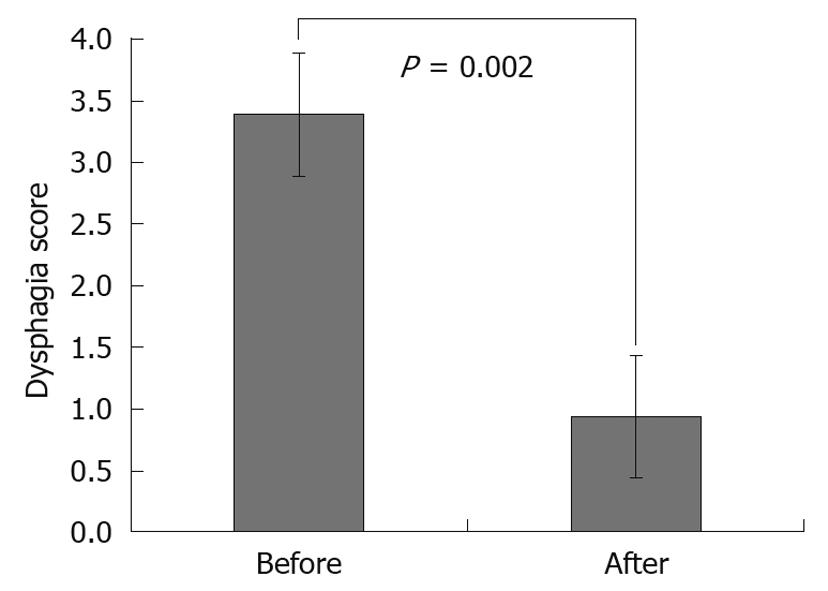

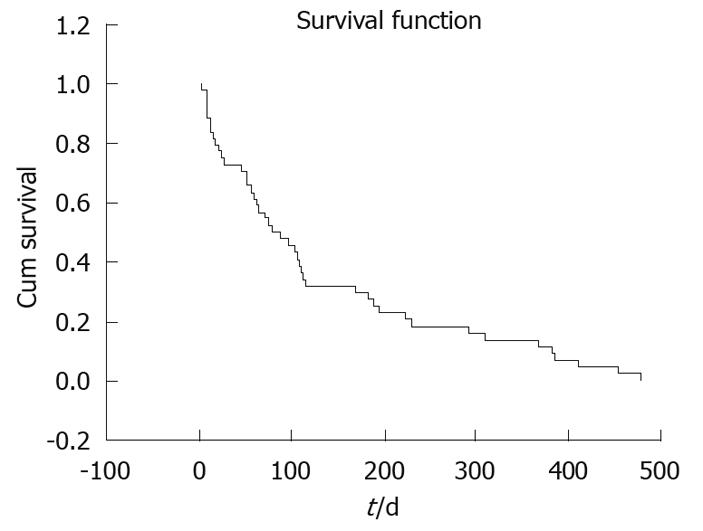

RESULTS: Stents were successfully implanted in 90 patients using fluoroscopic guidance. Reasons for stent implantation in these patients were esophageal stricture (77/90, 85.5%), external pressure (8/90, 8.8%) and tracheo-esophageal fistula (5/90, 5.5%). Dysphagia scores (mean ± SD) were 3.37 ± 0.52 before and 0.90 ± 0.43 after stent implantation (P = 0.002). Intermittent, non-massive hemorrhage due to the erosion caused by the distal end of the stent in the stomach occurred in only one patient who received implementation at cardio-esophageal junction. Mean survival following stenting was 134.14 d (95% confidence interval: 94.06-174.21).

CONCLUSION: SEMS placement is safe and effective in the palliation of dysphagia in selected patients with malignant esophageal strictures.

- Citation: Dobrucali A, Caglar E. Palliation of malignant esophageal obstruction and fistulas with self expandable metallic stents. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(45): 5739-5745

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i45/5739.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5739

Patients with esophageal cancer and cancer of the gastro-esophageal junction commonly present with an advanced disease mainly because the esophagus is quite distendable and patients may not experience dysphagia until almost half of the luminal diameter is compromised[1]. At the time of diagnosis, a high percentage of patients with esophageal cancer have an advanced stage of disease and when the tumor is not operable, only palliative treatment is applicable, primarily to manage dysphagia[2]. Dysphagia is the most devastating symptom in malign stricture of the esophagus. Aspiration is another frequent symptom requiring palliative therapy. This is either aspiration of saliva or food as a result of complete dysphagia or a tracheo-esophageal fistula. Similar problems may occur due to local pressure, particularly in patients with advanced lung cancer or mediastinal tumors. Early palliation of dysphagia and other symptoms is important in terms of nutritional status and a good quality of life. Among palliative treatments, radiotherapy, laser therapy and conventional plastic endoprostheses have a limited effect in preventing rapid weight loss due to malnutrition[3].

Several self expandable metallic stents (SEMS) are now available and have been used widely to provide immediate symptomatic relief of malignant dysphagia. They are useful for patients with poor functional status who cannot tolerate radiotherapy or chemotherapy, who have advanced metastatic disease, or in whom previous therapy has failed[3]. The aim of this report was to summarize our experience with expandable metal stents for palliation of malignant dysphagia in our 90 patients.

From September 2002 to December 2009, 90 patients (65 men, 25 women; mean age 61.57 years, range 38-85 years) with malignant inoperable esophageal obstruction and high grade dysphagia or fistula were treated using flexible self-expanding metallic stents. Surgery was considered to be contraindicated in all patients due to the patients’ poor general condition, the advanced stage of tumors, untreatable tumor recurrence or distant metastases. The ability to swallow was expressed as a dysphagia score. The scoring system was modified from that reported by Mellow and Pinkas; a score of 0 denoted the ability to eat a normal diet; 1, the ability to eat some solid food; 2, the ability to eat semisolid only; 3, the ability to swallow liquids only; and 4, complete dysphagia[4]. The data were compared with that published in the literature. All patients gave their informed consent for the procedure.

We employed self-expendable covered metallic esophageal stents from different companies (Boston Scientific, Watertown, MA, USA and Micro-Tech, Nanjing, China) in 76 patients. A covered self expanding stent was used in 5 patients with esophagotracheal fistulas. Diameters and length of covered stents varied between 18 and 20 mm, and 6 and 15 cm, respectively. Uncovered metallic stents (Ultraflex Boston Scientific, Watertown, MA, USA) were used in 14 patients. Diameters and length of uncovered stents varied between 18 and 23 mm, and 10 and 15 cm, respectively.

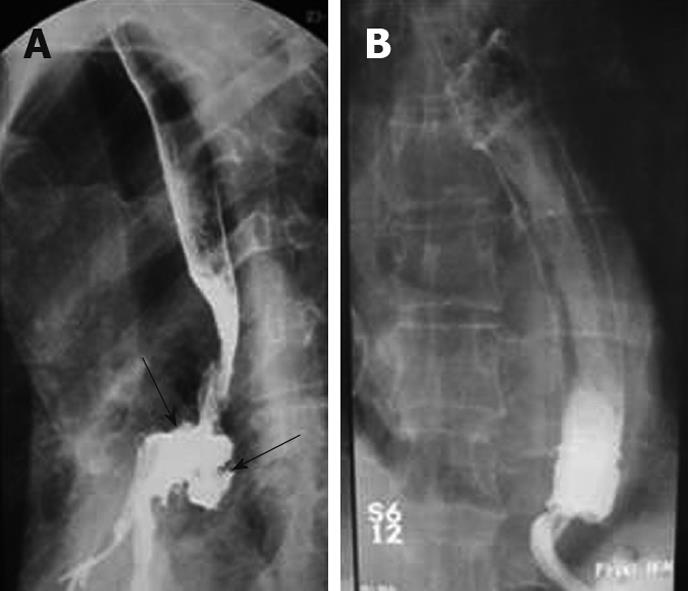

Before stent implantation, patients were prepared by administering conscious sedation analgesia (2.5-5 mg midazolam and 25-50 mg meperidine iv) The entire length of tumor stenosis and the location of the esophagotracheal fistula, if available, were precisely determined by an endoscope with an 11 mm diameter. High-grade strictures that could not pass an endoscope were opened prior to stenting to a diameter of at least 8-10 mm using a balloon dilator. After the preparatory treatment, the upper gastrointestinal tract was inspected endoscopically and the tumor margins on both sides were marked on the patients’ skin with metallic markers. After the placement of a guidewire into the stomach and the removal of the endoscope, the stent introducer was inserted over the guidewire into the esophagus under fluoroscopic guidance. The stent was positioned under fluoroscopic control with guidance of radio-opaque skin markers and then released from the delivery system. The stents expanded by themselves within 10-60 s. After another minute, the delivery system and the guidewire were carefully removed. After retraction of the delivery system, an immediate endoscopic check was made (Figure 1). A plain chest radiograph and a contrast study using swallowed water-soluble contrast medium were performed to ensure the correct positioning and expansion of the stent and to exclude perforation. In cases of esophago-tracheal fistula, a radiographic control using a water-soluble contrast medium was carried out (Figure 2). These patients were advised to consume only liquids until the stent position was checked. Then they had semisolid or solid food, as individually tolerated. Most patients were discharged on an outpatient basis and were instructed to start oral ingestion the same day. Anti reflux measures (proton pomp inhibitors and/or prokinetic agents) were administered to patients whose prosthesis extended beyond the gastroesophageal junction. We did not use antireflux stents.

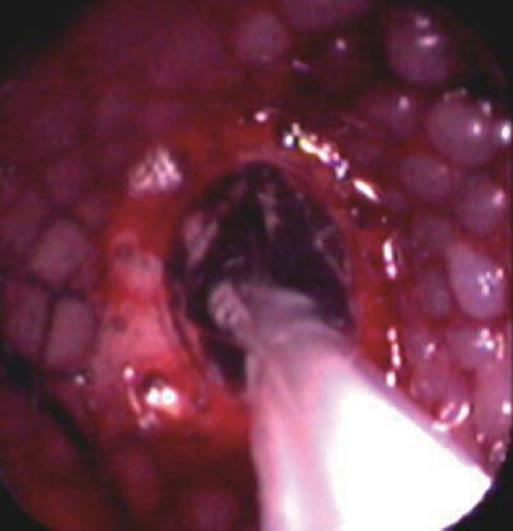

In some cases, because of the kinking of the esophageal lumen due to malign stricture, insertion of the stent introducer was difficult. In such cases, an endoscope was inserted after the introducer to help push it through the narrowed malign segment. In 3 cases with distal esophageal polypoid tumors, debulking was performed with a polypectomy snare because of extensive vegetation in the lumen preventing stent positioning and expansion. In 17 cases with insufficient stent expansion due to tight stricture, an endoscopic balloon dilatation through the opened stent was performed immediately after stenting to obtain an appropriate passageway (Figure 3).

An exploratory analysis was performed by using SPSS 13.0. Analysis of variance was used for non-categorical (continuous) data and the χ2 test was used for categorical data. Survival data were assessed by the Kaplan-Meier method.

A total of 100 expandable metal stents were placed in 90 patients for malignant dysphagia caused by esophageal cancer or extrinsic compression. Fifteen uncovered SEMS were placed in 14 patients and 85 covered stents were placed in 76 patients. Our series consisted of 25 women and 65 men with a mean ± SD age of 61.57 ± 12.05 years (range, 38-85 years). The mean size of the strictured segment of the esophagus where the stent was implanted was 7.14 ± 2.67 cm. The primary reason for stenting was esophageal stenosis alone in 77 patients (85.5%), followed by esophageal extrinsic compression in 8 patients (8.8%) and trachea-esophageal fistula in 5 patients (5.5%). In one patient stenting was performed in both his esophagus and the bronchus. In 4 cases, when the stent was opened in an inappropriate position, the stent was removed by pulling the attached string and a new stent was reinserted. Endoscopic balloon dilatation was performed before stenting in 27 patients (30%). Almost all patients improved in terms of oral intake. After the procedure, 84.4% of the patients (76/90) did not report any dysphagia during follow-up. Before stent placement, mean dysphagia score was 3.37 ± 0.52; after stent placement, mean dysphagia score was 0.90 ± 0.43 (P = 0.002) (Figure 4). There were no clinically significant complications during the insertion of stents. With respect to complications associated with stents, migration was noted in 4 patients (5%). Intermittent, non-massive hemorrhage due to the erosion caused by the distal end of the stent in the proximal stomach occurred in one patient who had received stent implantation in the cardio-esophageal junction. Migration was noted after 140 d on average (after 419 d in the first patient, after 69 d in the second patient, after 45 d in the third patient and after 27 d in the fourth patient). Migrations occurred following chemotherapy in 3 of the patients. Proximal tumor overgrowth was observed after 165 d on average following stenting in 6 patients (8.1%). Tumor overgrowth was observed within the first month following stenting only in one patient (at day 13). A second extendable stent was implanted in all of these patients. Minimal tissue ingrowth was detected in 3 patients (3.3%) treated with the uncovered stent and none had overt dysphagia.

Mean survival following stenting was 134.14 d [95% confidence interval: 20.45 (94.06-174.21)] (Figure 5). Restenting was needed in 10 patients (Table 1). No patient had esophageal perforation or procedure-related death. Dilatation was performed in 27 patients pre-operatively via a 12-16 mm balloon dilator for high grade strictures. Argon plasma coagulation was performed for one patient because of proximal tumor overgrowth.

| Age (yr) | Sex | Reason for restenting | Tumor location (stage) | Stenosis location | Dilatation | Stent type |

| 62 | M | Proximal overgrowth | Gastric (T4) | Distal | No | 6 cm, 20 mm CVRD |

| 52 | M | Proximal overgrowth | Lung Tm | Middle | No | 6 cm, 20 mm CVRD |

| 54 | M | Proximal overgrowth | Gastric (T4) | Distal | APC | 6 cm, 20 mm CVRD |

| 71 | M | Proximal overgrowth | Esophagus (T4) | Distal | No | 6 cm, 20 mm CVRD |

| 75 | M | Migration | Lung Tm | Middle | No | 10 cm, 20 mm CVRD |

| 53 | M | Proximal overgrowth | Esophagus (T4) | Proximal | No | 6 cm, 18 mm CVRD |

| 64 | M | Migration | Esophagus (T3) | Middle | No | 10 cm, 18 mm CVRD |

| 67 | M | Migration | Esophagus (T4) | Distal | No | 10 cm, 20 mm UCVRD |

| 55 | F | Proximal overgrowth | Gastric (T4) | Distal | No | 15 cm, 20 mm CVRD |

| 49 | F | Migration | Esophagus (T4) | Distal | No | 6 cm, 20 mm CVRD |

Table 2 illustrates the localizations of the stents, the reasons for stenting and the patients’ demographic data.

| n (%) | |

| Total No. of patients | 90 |

| Mean age (yr, range) | 61.57 (38-85) |

| Male/female | 65/25 (72.2/27.8) |

| Present illness | |

| Esophagus carcinoma | 54 (60.0) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 47 (52.2) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 7 (7.7) |

| Gastric carcinoma (and cardiac) | 20 (22.2) |

| Lung carcinoma | 16 (17.7) |

| Location of obstruction | |

| Proximal | 5 (5.6) |

| Middle | 31 (34.4) |

| Distal | 54 (60.0) |

| Restenting | 10 (11.1) |

Our results suggest that SEMS provide a rapid and effective palliation for dysphagia in malignant stenosis, and low morbidity is associated with the procedure. In our study, all patients had significant relief of dysphagia. The frequency of the common conditions associated with stenting as identified in our study are presented in Table 3, in comparison with data reported from other studies[5-15].

| Series | n | Dilation rate (%) | Stents uncovered | Perforation rate (%) | Migration rate (%) | Overgrowth rate (%) | Ingrowth rate (%) | Reintervention rate (%) | Median survival (d) |

| Present series | 90 | 30.0 | 15/85 | 0 | 4.4 | 6.6 | 3.3 | 15.5 | 134 |

| Wilkes et al[5]1 | 98 | 8 | 95/5 | 0 | 3.1 | 25.5 | - | 39.8 | 100 |

| Adam et al[6] | 42 | 100 | 45/55 | 0 | 19 | 2.3 | 9.5 | 36 | 53 |

| Knyrim et al[7]2 | 21 | 0 | 100/0 | 0 | 0 | 9.5 | 14.2 | 3.8 | 167 |

| Sarper et al[8] | 41 | 100 | 19/81 | 4.9 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | - | 94 |

| Siersema et al[9] | 100 | 7 | 0/100 | 6 | 13 | 10 | 0 | 49 | 109 |

| Christie et al[10] | 100 | 77 | 76/24 | 1 | 8.7 | 4 | 29.1 | 51 | - |

| Wengrower et al[11]3 | 81 | - | 100/0 | 3.6 | 5.95 | 2.4 | 0 | - | 120 |

| De Palma et al[12]2 | 19 | 0 | 100/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.5 | - | 198 |

| Kozarek et al[13] | 38 | 100 | 5/95 | 3 | 18.4 | 23.6 | 5.2 | 80 | 90 |

| White et al[14]1 | 70 | 100 | 57/43 | 2.8 | 0 | 1.4 | 2.8 | - | - |

| Maroju et al[15]1 | 30 | - | 9/91 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 10 | - | 161 |

Palliation is often difficult to achieve in patients with esophageal obstruction as a result of cancer. Among many endoscopic and nonendoscopic treatment alternatives for palliation of cancer-related dysphagia, stenting with SEMS is one of the main options. It is useful for patients with poor functional status who cannot tolerate radiation or chemotherapy, who have advanced metastatic disease, or in whom previous therapy has failed[16]. It can be concluded that stents provide better oral intake and quality of life compared to surgical palliation techniques. Despite the substantially higher cost of expandable metal stents as compared to traditional rigid plastic esophageal stents, there are substantial overall cost savings resulting from the reduction in the number of days of hospitalization for surgery and possible complications[7]. The majority of our subjects were patients who were referred to our clinic for dysphagia palliation from different centers and none were hospitalized after stenting. Our experience supported that SEMS could be inserted in outpatients, reducing the cost of treatment.

It has been shown that dysphagia was relieved in approximately 90% of patients who received an expendable metal stent[7,12,17]. Compared to other palliative methods, the most significant and fastest improvement in swallowing is achieved in patients undergoing implantation of SEMS[6,14,18,19]. Improvements in dysphagia were achieved in almost all of our patients following stenting. While the mean dysphagia score was 3.37 before stenting, the score was 0.90 following SEMS (P = 0.002). This decrease in dysphagia score is consistent with the literature. Recurrent dysphagia due to device migration and proximal overgrowth occurred in 10/90 (11.1%) of those who received SEMS. No significant difference was found between mean decreases in dysphagia scores in patients who were implanted with covered and uncovered stents (mean decreases in dysphagia scores in the 2 groups were 2.48 ± 0.53, 2.42 ± 0.51, respectively; P = 0.487). Covered and uncovered stents are equally good for dysphagia palliation[20].

Esophageal expandable metal stents are also used to treat tracheo-esophageal fistulas due to cancer. Tracheo-esophageal fistulas develop in patients with advanced esophageal and lung cancer and lead to devastating symptoms as a result of continuous aspiration of saliva and food. Survival over 30 d is rare in these patients, unless they undergo an occluding procedure using an endoprosthesis[18,21-25]. Noncovered stents are not suitable for the treatment of fistulas, because the esophageal contents can pass easily through the mesh and into the esophageal defect. The covered types of metal stents are considered as the primary choice of treatment since treatment of fistula with SEMS improves survival[18,26,27]. In our study group, fistulas were successfully closed with covered stents in all patients with a fistula. All 5 of these patients had primary lung tumors.

Stents were implanted in 5 of our patients because of proximal constriction within 4 cm. The Ultraflex type of covered stent was implanted in all these patients. Stent intolerability due to foreign body sensation, aspiration, perforation, proximal migration or pain was not observed in any of these patients. Verschuur et al[28] reported 44 patients had a malignant stricture within 4 cm of the upper esophageal sphincter. In this study, dysphagia improved in most patients, and the occurrence of complications and recurrent dysphagia was comparable to that in patients who underwent stent placement in the mid and distal esophagus. It has been reported that 5%-15% of patients had a foreign body sensation; however, in none of the patients was stent removal indicated[29]. There is a continuing debate about the advisability of SEMS placement for proximal esophageal cancer. If placed, it is frequently recommended that a distance of 2 cm below the upper esophageal sphincter should be maintained while placing a stent.

Intraprocedural complications of endoscopic stenting include those associated with sedation, aspiration, malpositioning of the stent, and esophageal perforation. Immediate postprocedural complications may include chest pain, bleeding, and tracheal compression, with resultant airway compromise and respiratory arrest. Late complications include distal or proximal stent migration, formation of an esophageal fistula, bleeding, perforation, and stent occlusion. Approximately 0.5%-2% of patients who undergo the procedure die as a direct result of placement of an expandable metal stent[30]. No patients died during the procedure in our patient group. Perforation of the esophageal wall is potentially related to the device itself and prior chemoradiotherapy[31]. This complication is presumably due to stent-induced pressure necrosis within devitalized esophageal tissue. The majority of stenting complications are reported in the literature to occur with plastic endoprostheses. In a study by Knyrim et al[7], 42 patients with metallic stent and plastic endoprosthesis were compared and the frequency of complications was reported to be less in patients who were implanted with metallic stents (0 and 9 patients, respectively). Two prospective, randomized, controlled trials have shown a significantly lower rate of procedural complications using expanding metal stents[7,12]. Perforation as a direct complication of stent placement was not seen in our patients. This result of perforation compares favorably with other studies[18,32-37]. In contrast to placement of conventional esophageal stents, placement of expendable metal stents do not require a large-bore bougienage, thereby minimizing the risk of perforation and facilitating the insertion procedure. However, in our series balloon dilatation was performed in 27 patients before stenting. The frequency of dilatation has been reported to be in the range of 0%-100% in the literature[7,12,13].

A tracheoesophageal (TE) fistula is one of the late complications that may occur after SEMS. The incidence of fistulas following stenting has been reported as 0%-10% in the literature. The type of the implanted stent was found to have no role in fistula development[6,18,38,39]. Fistulas should be treated with placement of additional, overlapping covered metallic stents. Retrospective analysis of our patients did not reveal any patient developing fistulas after stenting. Kozarek et al[13] did not find an association between perforation, bleeding or TE fistula development in patients who had received previous chemotherapy/irradiation. Consistent with the findings reported by Kozarek et al[13], TE fistulas did not develop in any of our patients who were receiving treatment.

Stent migration may be a bothersome problem in SEMS. Studies have reported the incidence of late migration from 0% to 58% for different types of covered stents. A higher incidence of late migration of all types of covered stents was observed compared to the uncovered types[6,18,21,40]. Stent migration was noted in 4 (4.4%) of our patients; 3 of these patients had covered and one had an uncovered type of stent.

Another ongoing issue with stents is the occurrence of recurrent dysphagia because of stent migration, tumoral or nontumoral tissue growth and food impaction. Frequencies of recurrent dysphagia associated with overgrowth, ingrowth and obstruction due to food impaction reported in the literature varies between 17% and 33%, somewhat higher than those observed in our study[2,7]. As the malignant tumor continues to grow after stent implantation, the growth of tumor tissue through the stent lumen (ingrowth) and extension over the stent borders (overgrowth) are 2 major late complications[10,41,42]. The disadvantages of uncovered stents are tumor ingrowth and recurrent obstruction. Covered stents have been designed to prevent ingrowth. Ingrowth in uncovered stents has been reported in literature to be in the range of 0%-100%[6,10,11,38,39]. Authors who used partially covered stents reported the incidence of growth in the uncovered ends of stents between 2% and 25% in different series[10,41,42]. The frequency in covered stents has been reported as 0%-53%[2,6]. In our study, tumor ingrowth was found in 3 patients (3.3%) treated with uncovered stents.

Overgrowth is the result of progression of malignancy rather than a failure or a complication of the stent. It is usually seen in 2.3%-30% of patients after a mean period of 2-4 mo after stent replacement[2,6,9,39,43]. Overgrowth may not always be due to the tumor but may also result from benign epithelial hyperplasia or granulation tissue. The most frequent symptom in cases of overgrowth was dysphagia in our group. Following stenting, 6 patients (6.6%) were restented due to restenosis associated with proximal overgrowth. Restenosis associated with early proximal overgrowth occurred in only one of our patients (at day 13). Stent migration may facilitate development of overgrowth formation though it may not be possible to confirm this complication endoscopically. The use of covered stents may help decrease tumor ingrowth, although it will not affect tumor overgrowth. The most frequently used method for the treatment of tumor overgrowth is the placement of a second stent. Argon plasma coagulation was performed additionally in one of our patients with proximal tumor overgrowth. Stent obstruction was observed in 4 of our patients as a result of food impaction, and stents were cleaned endoscopically in all patients.

Hematemesis is also a possible complication after SEMS insertion, and the incidence in our study was 1.1% (1/90). This complication could have been the result of pressure necrosis, the natural progress of the disease, or esophageal or gastric trauma from the sharp end of the stent.

Mean survival after stenting, reported in the literature, varies between 53 and 198 d[6,7,12]. In our study mean survival after stenting was 134 d. Overall survival time in our study was not significantly different from others in the literature. It has been shown that survival is influenced by the type and stage of the underlying disease.

It has been reported that SEMS are being implanted in the absence of fluoroscopic guidance in some centers and that this is a safe approach[5,6,15]. We believe that esophageal stenting under fluoroscopic guidance with endoscopic control is safer.

In summary, in our retrospective screening, we noted that all of our patients had been stented with covered or uncovered metallic stents and that the use of these stents was safe and effective in rapid alleviation of dysphagia. The placement of a self-expandable metallic stent can improve the oral alimentation status. Esophageal fistulas can be completely and rapidly closed with placement of covered metallic endoprostheses. Esophageal stents are a means to an end: in the setting of malignant disease, they occlude TE fistulae or alleviate dysphagia, but do not affect the natural course of the disease process except by virtue of inadequate palliation or subsequent stent-related complications.

Self expandable metallic stents (SEMS) introduction plays an important role in the management of esophageal obstruction and fistula secondary to malignancy. Early palliation of dysphagia is important for the maintaining of nutritional status and life quality. SEMS provides a considerable palliation with low mortality and morbidity especially in patients with advanced disease.

This research is regarding to the efficacy and safety of SEMS in patients with esophageal obstruction or fistula due to advanced cancer.

The authors found that the covered and uncovered SEMS are equally effective for dysphagia palliation in malignant esophageal obstruction. This study is the most comprehensive retrospective review from Turkey about the palliation of malignant esophageal obstruction and fistula with SEMS. Also this study showed that it is possible to minimize the complications which may arise from SEMS placement.

The advantages of SEMS over the other palliative methods are rapidly improving of dysphagia, nutritional status and life quality. Stenting with covered SEMS is the most effective method in patients with malignant esophageal fistula.

Palliation of malign obstruction of esophagus via SEMS is a rapid and effective treatment. The authors summarized their own experience retrospectively and the manuscript is generally well written.

Peer reviewer: Tarkan Karakan, Associate Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Gazi University, Ankara 06500, Turkey

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Katsoulis IE, Karoon A, Mylvaganam S, Livingstone JI. Endoscopic palliation of malignant dysphagia: a challenging task in inoperable oesophageal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:38. |

| 2. | Saranovic Dj, Djuric-Stefanovic A, Ivanovic A, Masulovic D, Pesko P. Fluoroscopically guided insertion of self-expandable metal esophageal stents for palliative treatment of patients with malignant stenosis of esophagus and cardia: comparison of uncovered and covered stent types. Dis Esophagus. 2005;18:230-238. |

| 3. | Baron TH. Expandable metal stents for the treatment of cancerous obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1681-1687. |

| 4. | Mellow MH, Pinkas H. Endoscopic laser therapy for malignancies affecting the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. Analysis of technical and functional efficacy. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1443-1446. |

| 5. | Wilkes EA, Jackson LM, Cole AT, Freeman JG, Goddard AF. Insertion of expandable metallic stents in esophageal cancer without fluoroscopy is safe and effective: a 5-year experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:923-929. |

| 6. | Adam A, Ellul J, Watkinson AF, Tan BS, Morgan RA, Saunders MP, Mason RC. Palliation of inoperable esophageal carcinoma: a prospective randomized trial of laser therapy and stent placement. Radiology. 1997;202:344-348. |

| 7. | Knyrim K, Wagner HJ, Bethge N, Keymling M, Vakil N. A controlled trial of an expansile metal stent for palliation of esophageal obstruction due to inoperable cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1302-1307. |

| 8. | Sarper A, Oz N, Cihangir C, Demircan A, Isin E. The efficacy of self-expanding metal stents for palliation of malignant esophageal strictures and fistulas. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:794-798. |

| 9. | Siersema PD, Hop WC, van Blankenstein M, van Tilburg AJ, Bac DJ, Homs MY, Kuipers EJ. A comparison of 3 types of covered metal stents for the palliation of patients with dysphagia caused by esophagogastric carcinoma: a prospective, randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:145-153. |

| 10. | Christie NA, Buenaventura PO, Fernando HC, Nguyen NT, Weigel TL, Ferson PF, Luketich JD. Results of expandable metal stents for malignant esophageal obstruction in 100 patients: short-term and long-term follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1797-1801; discussion 1801-1802. |

| 11. | Wengrower D, Fiorini A, Valero J, Waldbaum C, Chopita N, Landoni N, Judchack S, Goldin E. EsophaCoil: long-term results in 81 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:376-382. |

| 12. | De Palma GD, di Matteo E, Romano G, Fimmano A, Rondinone G, Catanzano C. Plastic prosthesis versus expandable metal stents for palliation of inoperable esophageal thoracic carcinoma: a controlled prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:478-482. |

| 13. | Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, Brandabur JJ, Patterson DJ, Low D, Hill L, Raltz S. Expandable versus conventional esophageal prostheses: easier insertion may not preclude subsequent stent-related problems. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:204-208. |

| 14. | White RE, Mungatana C, Topazian M. Esophageal stent placement without fluoroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:348-351. |

| 15. | Maroju NK, Anbalagan P, Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N. Improvement in dysphagia and quality of life with self-expanding metallic stents in malignant esophageal strictures. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:62-65. |

| 16. | Bethge N, Sommer A, von Kleist D, Vakil N. A prospective trial of self-expanding metal stents in the palliation of malignant esophageal obstruction after failure of primary curative therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:283-286. |

| 17. | Roseveare CD, Patel P, Simmonds N, Goggin PM, Kimble J, Shepherd HA. Metal stents improve dysphagia, nutrition and survival in malignant oesophageal stenosis: a randomized controlled trial comparing modified Gianturco Z-stents with plastic Atkinson tubes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:653-657. |

| 18. | Raijman I, Siddique I, Ajani J, Lynch P. Palliation of malignant dysphagia and fistulae with coated expandable metal stents: experience with 101 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:172-179. |

| 19. | Ahmad NR, Goosenberg EB, Frucht H, Coia LR. Palliative Treatment of Esophageal Cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1994;4:202-214. |

| 20. | Watkinson A, Ellul J, Entwisle K, Farrugia M, Mason R, Adam A. Plastic-covered metallic endoprostheses in the management of oesophageal perforation in patients with oesophageal carcinoma. Clin Radiol. 1995;50:304-309. |

| 21. | Song HY, Choi KC, Cho BH, Ahn DS, Kim KS. Esophagogastric neoplasms: palliation with a modified gianturco stent. Radiology. 1991;180:349-354. |

| 22. | Raijman I, Lynch P. Coated expandable esophageal stents in the treatment of digestive-respiratory fistulas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2188-2191. |

| 23. | Rahmani EY, Rex DK, Lehman GA. Z-stent for malignant esophageal obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1999;9:395-402. |

| 24. | Wong K, Goldstraw P. Role of covered esophageal stents in malignant esophagorespiratory fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:199-200. |

| 25. | Roy-Choudhury SH, Nicholson AA, Wedgwood KR, Mannion RA, Sedman PC, Royston CM, Breen DJ. Symptomatic malignant gastroesophageal anastomotic leak: management with covered metallic esophageal stents. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:161-165. |

| 26. | Morgan RA, Ellul JP, Denton ER, Glynos M, Mason RC, Adam A. Malignant esophageal fistulas and perforations: management with plastic-covered metallic endoprostheses. Radiology. 1997;204:527-532. |

| 27. | Freitag L, Tekolf E, Steveling H, Donovan TJ, Stamatis G. Management of malignant esophagotracheal fistulas with airway stenting and double stenting. Chest. 1996;110:1155-1160. |

| 28. | Verschuur EM, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Esophageal stents for malignant strictures close to the upper esophageal sphincter. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1082-1090. |

| 29. | Siersema PD. Treatment options for esophageal strictures. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:142-152. |

| 30. | Ramirez FC, Dennert B, Zierer ST, Sanowski RA. Esophageal self-expandable metallic stents--indications, practice, techniques, and complications: results of a national survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:360-364. |

| 31. | Muto M, Ohtsu A, Miyata Y, Shioyama Y, Boku N, Yoshida S. Self-expandable metallic stents for patients with recurrent esophageal carcinoma after failure of primary chemoradiotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2001;31:270-274. |

| 32. | Nicholson DA, Haycox A, Kay CL, Rate A, Attwood S, Bancewicz J. The cost effectiveness of metal oesophageal stenting in malignant disease compared with conventional therapy. Clin Radiol. 1999;54:212-215. |

| 33. | Boulis NM, Armstrong WS, Chandler WF, Orringer MB. Epidural abscess: a delayed complication of esophageal stenting for benign stricture. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:568-570. |

| 34. | Bethge N, Sommer A, Vakil N. Palliation of malignant esophageal obstruction due to intrinsic and extrinsic lesions with expandable metal stents. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1829-1832. |

| 35. | Cwikiel W, Tranberg KG, Cwikiel M, Lillo-Gil R. Malignant dysphagia: palliation with esophageal stents--long-term results in 100 patients. Radiology. 1998;207:513-518. |

| 36. | O'Sullivan GJ, Grundy A. Palliation of malignant dysphagia with expanding metallic stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:346-351. |

| 37. | Song HY, Do YS, Han YM, Sung KB, Choi EK, Sohn KH, Kim HR, Kim SH, Min YI. Covered, expandable esophageal metallic stent tubes: experiences in 119 patients. Radiology. 1994;193:689-695. |

| 38. | Acunas B, Rozanes I, Sayi I, Akpinar S, Terzioglu T, Kumbasar A, Gökmen E. Treatment of malignant dysphagia with nitinol stents. Eur Radiol. 1995;5:599-602. |

| 39. | Cwikiel W, Stridbeck H, Tranberg KG, von Holstein CS, Hambraeus G, Lillo-Gil R, Willén R. Malignant esophageal strictures: treatment with a self-expanding nitinol stent. Radiology. 1993;187:661-665. |

| 40. | Bartelsman JF, Bruno MJ, Jensema AJ, Haringsma J, Reeders JW, Tytgat GN. Palliation of patients with esophagogastric neoplasms by insertion of a covered expandable modified Gianturco-Z endoprosthesis: experiences in 153 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:134-138. |

| 41. | Wang MQ, Sze DY, Wang ZP, Wang ZQ, Gao YA, Dake MD. Delayed complications after esophageal stent placement for treatment of malignant esophageal obstructions and esophagorespiratory fistulas. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:465-474. |

| 42. | Lagattolla NR, Rowe PH, Anderson H, Dunk AA. Restenting malignant oesophageal strictures. Br J Surg. 1998;85:261-263. |

| 43. | Poyanli A, Sencer S, Rozanes I, Acunaş B. Palliative treatment of inoperable malignant esophageal strictures with conically shaped covered self-expanding stents. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:166-171. |