Published online Dec 7, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5722

Revised: July 10, 2010

Accepted: July 17, 2010

Published online: December 7, 2010

AIM: To present a new technique of cervical esophagogastric anastomosis to reduce the frequency of fistula formation.

METHODS: A group of 31 patients with thoracic and abdominal esophageal cancer underwent cervical esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination of the proximal esophageal stump into the stomach tube. In the region elected for anastomosis, a transverse myotomy of the esophagus was carried out around the entire circumference of the esophagus. Afterwards, a 4-cm long segment of esophagus was invaginated into the stomach and anastomosed to the anterior and the posterior walls.

RESULTS: Postoperative minor complications occurred in 22 (70.9%) patients. Four (12.9%) patients had serious complications that led to death. The discharge of saliva was at a lower region, while attempting to leave the anastomosis site out of the alimentary transit. Three (9.7%) patients had fistula at the esophagogastric anastomosis, with minimal leakage of air or saliva and with mild clinical repercussions. No patients had esophagogastric fistula with intense saliva leakage from either the cervical incision or the thoracic drain. Fibrotic stenosis of anastomoses occurred in seven (22.6%) patients. All these patients obtained relief from their dysphagia with endoscopic dilatation of the anastomosis.

CONCLUSION: Cervical esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination of the proximal esophageal stump into the stomach tube presented a low rate of esophagogastric fistula with mild clinical repercussions.

- Citation: Henriques AC, Godinho CA, Saad Jr R, Waisberg DR, Zanon AB, Speranzini MB, Waisberg J. Esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination into stomach: New technique to reduce fistula formation. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(45): 5722-5726

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i45/5722.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5722

Definitive curative treatment for cancer of the esophagus remains a challenge for surgeons[1-8]. The approach involves major surgery that has high morbidity and mortality rates, mainly due to pulmonary complications, cervical fistulas, stenosis of anastomosis, necrosis of the tubularized stomach, and mediastinitis[5,9-12].

Among these possible complications, fistula of the esophagogastric anastomosis represents one of the principal problems of esophagectomy. In several studies, the incidence has ranged from 0% to 50%, with most authors reporting a high incidence of this complication[4,6,13-18].

Although these fistulas usually have a favorable course, about 2% of cases can have a catastrophic outcome[5,16]. In cases in which the fistula does not lead directly to death, it can compromise quality of life, interfere with resumption of feeding, require laborious local care, and prolong hospital stay. Additionally, 30%-50% of those patients who present with fistula go on to develop stenosis[15,19-22].

Given this scenario and personal experience of a high incidence of cervical esophagogastric fistula in treatment of carcinoma of the esophagus[23], we decided to perform cervical esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination of the proximal esophageal stump into the stomach tube, and to analyze the incidence of fistula and stenosis formation following this procedure.

This study conformed to the regulations of The Human Ethics Research Committee at our Institution and with the Helsinki Declaration, revised in 1983.

Our study group consisted of 31 patients with thoracic or abdominal carcinoma of the esophagus, who underwent open access with subtotal esophagectomy and esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination of the proximal esophageal stump into the stomach tube. The study group included 27 (87.1%) men and four (12.9%) women, with a mean age of 60.2 ± 8.5 years (range: 44-74 years). Lesions were located in the medial third of the esophagus in 15 cases (48.3%) and the inferior third in 16 (51.6%).

The inclusion criteria for operation were: esophagogram with no abnormal axis deviation, lesions up to 5.0 cm long, absence of signs of invasion of the respiratory tree on bronchoscopy, and absence of signs of irresectability of the esophageal lesion or neoplastic dissemination on thoracic and abdominal helicoidal tomography. Cases in which an anesthetic or surgical procedure was contraindicated due to compromised clinical state and/or concurrent serious systemic disease were excluded from the study. The diagnosis was confirmed by upper esophageal endoscopy and biopsy: 25 (80.6%) patients had squamous cell carcinoma and the remaining six (19.3%) had adenocarcinoma.

All patients underwent preoperative clinical evaluation. Thirteen (41.9%) had serious clinical malnutrition as shown by weight loss of greater than 20% of normal weight. Tumor staging was performed using physical examination, thoracic radiography, barium esophography, thoracic and abdominal tomography, and bronchoscopy in patients whose lesions were situated in the medial third of the esophagus. Clinicopathological staging using the TNM classification by the UICC[24] was: stage I in two (6.4%) patients; stage IIA in five (16.1%); stage IIB in four (12.9%); stage III in 16 (51.6%); and stage IVA in four (12.9%).

In the absence of contraindications, a transhiatal esophagectomy followed by a cervical esophagogastroplasty was performed. All surgeries were carried out in parallel during the same operating period by two teams, with one team operating in the abdominal region and the other in the cervical region. Lymph node resection was done in both the abdominal and inferior mediastinal fields. In all cases, the tubularized stomach was placed into the cervical region by the posterior mediastinum.

The esophagus was dissected and separated from its neighboring structures in the cervical, thoracic and abdominal areas. In distally located tumors, the esophagus was sectioned in the cervical region, with care taken to preserve enough of the proximal end to allow 4.0 cm of esophagus to be inserted into the stomach, with a safe margin ≥ 5.0 cm. The esophagus was then pulled to the abdominal region, and the stomach sectioned with a linear stapler that released the surgical specimen.

To guarantee a sufficient margin for lesions that involved the middle third, the stomach was initially sectioned and tubularized, and the piece pulled up to the cervical region, where it was very carefully examined, and the surgical section site was chosen with a safe margin. If the margin was judged to be inadequate, end-to-end anastomosis was performed instead of invagination, and that patient was excluded from the study.

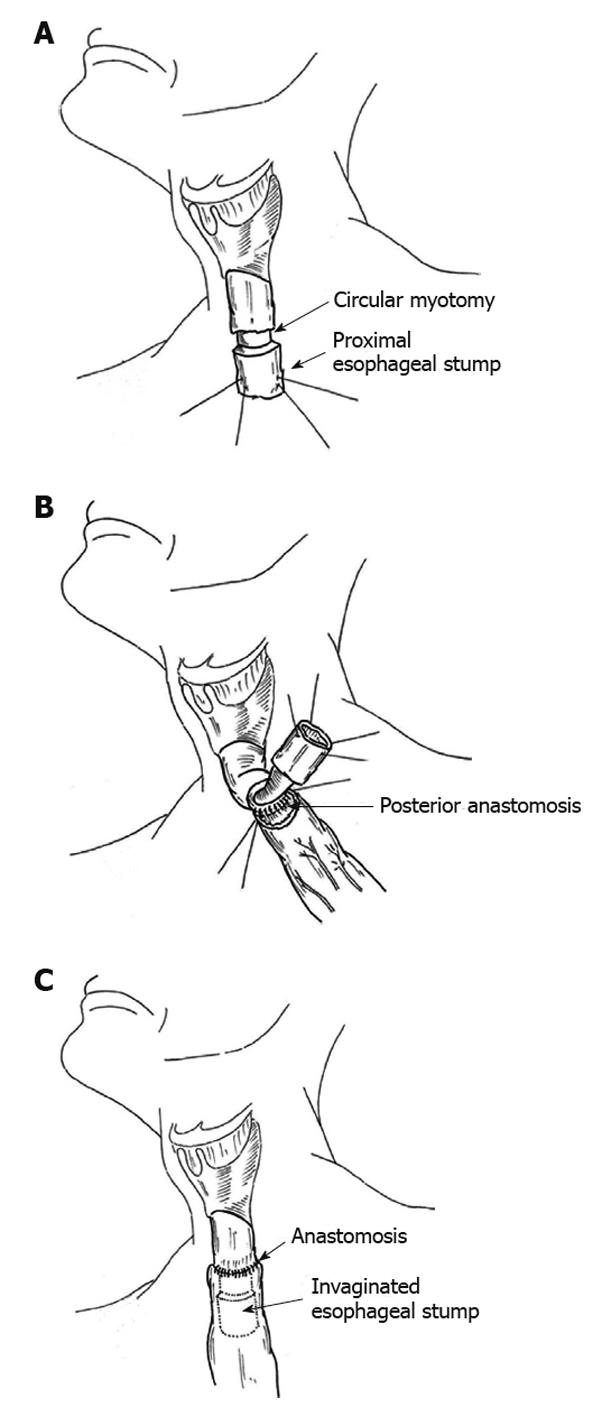

In the region that was selected for anastomosis, a transverse myotomy was carried out around the entire circumference of the esophagus (Figure 1A). The proximal border of the myotomy was anastomosed, with the tip of the tubularized stomach placed in the cervical region. The anastomosis of the posterior wall was performed first using interrupted sutures of 4-0 polydioxanone (Figure 1B). Subsequently, the 4-cm segment of esophagus was introduced or invaginated into the stomach and sutured to the anterior wall as per the posterior wall (Figure 1C). In all patients, extra-mucosal pyloroplasty was carried out, a nasogastric tube was also inserted, and the cervical region was drained by a laminar drain.

Oral feeding was typically started on the postoperative day 10, in the absence of signs of esophagogastric fistula. If a fistula was present, the affected site was treated, to maintain feeding by nasogastric tube. In this case, oral diet was begun following closure of the fistula.

No patients died intraoperatively. Postoperative minor complications occurred in 22 (70.9%) patients. Four (12.9%) patients had serious complications that led to death: two (6.4%) as a result of bronchopneumonia, one due to multiple organ failure after acute cholecystitis, and the other from sepsis following ischemic necrosis of the stomach; all of them with no relationship to the esophagogastric anastomosis.

Three (9.7%) patients had fistula at the esophagogastric anastomosis with minimal leakage of air or saliva; all of them with mild clinical repercussions. Two of these had a fistula on postoperative days 7 and 10, with the leak of a small quantity of air or saliva from the cervical incision and consequent formation of a bubble during swallowing. In these two patients, spontaneous closure occurred after 10 and 5 d, respectively. The third case had a seropurulent pleural effusion on postoperative day 13, which was later drained. There was a negligible quantity of secretion from the pleural drain, which indicated a mild blocked esophago-pleurocutaneous fistula. This patient had no adverse effects from this and was discharged from hospital on postoperative day 23. No patients had esophagogastric fistula with intense saliva leakage from either the cervical incision or the thoracic drain.

Postoperative stricture of the anastomosis occurred in seven (22.6%) patients; in six of these, this appeared within 16-60 d, and the last appeared at 12 mo after surgery. All of these patients obtained relief from their dysphagia with endoscopic dilatation of the anastomosis, with the number of sessions required ranging from one to seven (mean = 3). One (3.2%) patient with a lesion located in the inferior third of the esophagus had recurrence of the cancer in the area of the anastomosis and required a nasogastric tube. The other complications were successfully treated: dysphonia in 15 (48.4%), bronchopneumonia in four (12.9%), atelectasis in two (6.4%), renal failure in two (6.4%), and wound infection in one (3.2%). Dysphonia was temporary and resolved after a few weeks in all cases. Patients with pre-renal renal failure responded well to expansion with fluids. Atelectasis was reversed with respiratory physiotherapy. The mean length of hospital stay was 15.2 d, with a range of 13-35 d (Table 1).

| Complication | n (%) |

| Dysphonia | 15 (48.4) |

| Anastomosis stricture | 7 (22.6) |

| Bronchopneumonia | 6 (19.3) |

| Anastomosis fistula | 3 (9.7) |

| Atelectasis | 2 (6.4) |

| Renal failure | 2 (6.4) |

| Gastric ischemic necrosis | 1 (3.2) |

| Acute cholecystitis | 1 (3.2) |

| Wound infection | 1 (3.2) |

Esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination is a modification of a technique that is performed to reduce fistula formation at the anastomosis site[22]. Szücs et al[22] have reported 108 patients that underwent esophagectomy with esophagogastric anastomosis and telescoping of a 10-15-mm length of the esophageal end into the stomach. Twelve (11.1%) of these patients developed fistula at the anastomotic site. We chose to invaginate a 4.0-cm segment made up of all the layers of the esophagus wall, a much longer segment than that suggested by Szücs et al[22] and we added a transverse myotomy around the circumference of the esophagus. Our intention was not only to cover the entire site of the anastomosis, but also to encourage the discharge of saliva at a lower region, while attempting to leave the anastomosis site out of alimentary transit. To this end, it was necessary to invaginate a longer segment that consisted of all the layers of the wall of the esophagus, such that the inserted portion remained in the shape of a tube in the interior of the stomach.

To execute the anastomosis, we elected a region at the proximal esophagus where the suture would be placed, and preserved 4.0 cm of esophagus to be invaginated into the stomach. At this point, a transverse myotomy was done around the circumference of the esophagus. We sutured the proximal border of the myotomy together with the seromuscular layer of the stomach. The purpose of the myotomy was to create a border with viability in the muscular layer of the esophagus, to be sutured with the seromuscular layer of the stomach, and also to elongate the esophageal tube to be inserted into the stomach.

The point of esophageal section must be chosen to allow for a safe margin, because carcinoma of the esophagus can disseminate within the wall to sites distal from the principal lesion[8,25-28]. To perform an esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination, it is necessary to save 4.0 cm more of proximal esophagus than for anastomosis without invagination. If it is not possible to achieve an adequate margin, the invagination procedure should be abandoned.

In our view, the fact that this technique conserves 4.0 cm more of the esophagus does not detract from the radical nature of the operation. Upon constructing a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination, the amount of remaining esophagus is no greater than that usually left when anastomosis is done in the thoracic apex. Walther et al[6], in a prospective randomized study, have compared cervical with intrathoracic esophagogastric anastomosis. They have concluded that the withdrawal of an extra 5.0 cm of esophagus to perform anastomosis in the neck does not affect the 5-year survival rate. Consequently, we believe that following all the recommendations and leaving a secure margin, esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination does not breach any radical oncological principles.

The diagnosis of fistula of the esophagogastric anastomosis was made based exclusively on clinical criteria, given that a radiological study with water-soluble contrast medium has low sensitivity and a high incidence of false-negative results[29]. None of our cases operated upon by esophagectomy with esophagogastric anastomosis and invagination developed fistula with heavy egress of saliva from the cervical incision. Compared with results from the literature[4,6,13-18,30] which show an incidence of fistulas of 0%-50%, cervical esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination had a low incidence of fistula formation, with only one case (3.4%) having clinical repercussions.

It is possible that esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination did not influence the factors responsible for the formation of the fistula. Moreover, it is likely that points of dehiscence could occur along the suture line similarly when we perform the end-to-end technique. However, as the saliva flows to an area below the anastomosis, these points of dehiscence probably can undergo rapid regeneration. On the other hand, in cases without invagination, the saliva discharges directly into the area of the suture with dehiscence, which provokes local inflammation and infection, thereby delaying the healing process of the suture line and enlarging this area.

In view of this mechanism, we believe that the three cases observed of fistula formation in esophagogastric anastomosis presented with mild clinical repercussions, even when the fistula was directed toward the pleural space. We also believe that, despite fistula with minimal clinical repercussions, the technique of esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination can still prove advantageous over the method without invagination.

In the present study, seven (24.1%) cases developed postoperative strictures of anastomosis; this rate lies within the 5%-45% limit described by other authors[15,19,20]. We believe that this result could have been due to the fact that anastomosis with invagination did not influence the factors that might predispose the formation of fistulas, such as ischemia in the proximal portion of the gastroplasty. In this situation, the points of dehiscence would have occurred along the suture line at a similar rate to anastomosis without invagination. However, the presence of a fistula was not always identified using clinical criteria, possibly due to the fact that saliva discharges below the point of the dehiscence. These events could possibly trigger a fibrotic reaction and scarring, with subsequent stenosis formation in the anastomosis.

We conclude that performing cervical esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination of the proximal esophageal stump into the stomach in subtotal esophagogastrectomy with gastroplasty in patients with carcinoma of the thoracic and abdominal regions of the esophagus represents a potential real advantage of this technique over other conventional techniques without invagination.

However, prospective, randomized, and controlled studies that involve esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination of the proximal esophageal stump into the tip of the stomach placed to the cervical region are needed to confirm the initials results obtained in this study.

Definitive curative treatment for cancer of the esophagus remains a challenge for surgeons. The approach involves major surgery that has a high morbidity and mortality rate, mainly due to pulmonary complications, cervical fistulas, stenosis of anastomosis, necrosis of the tubularized stomach, and mediastinitis. Among these possible complications, fistula of the esophagogastric anastomosis represents one of the principal problems of esophagectomy. Incidence in several studies has ranged from 0% to 50%, with most authors reporting a high incidence of this complication.

In view of the high incidence of esophagogastric fistulas associated with significant levels of mortality and morbidity, several surgical techniques have been tried to reduce the frequency of fistula formation. These approaches include protection of the anastomosis with fibrin glue, anastomosis in two stages, gastric fundus rotation, microsurgical revascularization of the transposed viscera, mechanical anastomosis, laparoscopic construction of the gastric tube 5 d before esophagectomy, preservation of the vascular arcade of the splenic hilum, administration of prostaglandin E1, and anastomosis with invagination.

Esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination is a modification of a technique that is performed to reduce fistula formation at the anastomosis site. We chose to invaginate a 4.0-cm segment made up of all the layers of the esophagus wall, a much longer segment than that suggested by other authors, and we added transverse myotomy around the circumference of the esophagus. Our intention was not only to cover the entire site of the anastomosis, but also to encourage the discharge of saliva at a lower region, while attempting to leave the anastomosis site without contact with saliva. To this end, it was necessary to invaginate a longer segment that consisted of all the layers of the wall of the esophagus, such that the inserted portion remained in the shape of a tube in the interior of the stomach.

Cervical esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination of the proximal esophageal stump into the stomach in subtotal esophagogastrectomy with gastroplasty in patients with carcinoma of the thoracic and abdominal regions of the esophagus is associated with a low incidence of esophagogastric fistula, while having similar stenosis rates to anastomosis without invagination.

Cervical esophagogastric anastomosis with invagination of the proximal esophageal stump into the stomach tube is a new technique of cervical esophagogastric anastomosis to reduce the frequency of fistula formation.

This is an interesting report on a novel technique for cervical esophagogastric anastomosis after esophagectomy and gastric replacement.

Peer reviewer: Marcelo A Beltran, MD, Chairman of Surgery, Hospital La serena, PO Box 912, La Serena, IV REGION, Chile

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Gockel I, Heckhoff S, Messow CM, Kneist W, Junginger T. Transhiatal and transthoracic resection in adenocarcinoma of the esophagus: does the operative approach have an influence on the long-term prognosis? World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:40. |

| 2. | Johansson J, DeMeester TR, Hagen JA, DeMeester SR, Peters JH, Oberg S, Bremner CG. En bloc vs transhiatal esophagectomy for stage T3 N1 adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus. Arch Surg. 2004;139:627-631; discussion 631-633. |

| 3. | Korst RJ. Surgical resection for esophageal carcinoma: speaking the language. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2211-2212. |

| 4. | van Lanschot JJ, van Blankenstein M, Oei HY, Tilanus HW. Randomized comparison of prevertebral and retrosternal gastric tube reconstruction after resection of oesophageal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1999;86:102-108. |

| 5. | Rentz J, Bull D, Harpole D, Bailey S, Neumayer L, Pappas T, Krasnicka B, Henderson W, Daley J, Khuri S. Transthoracic versus transhiatal esophagectomy: a prospective study of 945 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:1114-1120. |

| 6. | Walther B, Johansson J, Johnsson F, Von Holstein CS, Zilling T. Cervical or thoracic anastomosis after esophageal resection and gastric tube reconstruction: a prospective randomized trial comparing sutured neck anastomosis with stapled intrathoracic anastomosis. Ann Surg. 2003;238:803-812; discussion 812-814. |

| 7. | Siewert JR, Ott K. Are squamous and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus the same disease? Semin Radiat Oncol. 2007;17:38-44. |

| 8. | Kunisaki C, Makino H, Takagawa R, Yamamoto N, Nagano Y, Fujii S, Kosaka T, Ono HA, Otsuka Y, Akiyama H. Surgical outcomes in esophageal cancer patients with tumor recurrence after curative esophagectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:802-810. |

| 9. | Dimick JB, Goodney PP, Orringer MB, Birkmeyer JD. Specialty training and mortality after esophageal cancer resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:282-286. |

| 10. | Cassivi SD. Leaks, strictures, and necrosis: a review of anastomotic complications following esophagectomy. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;16:124-132. |

| 11. | Goan YG, Chang HC, Hsu HK, Chou YP. An audit of surgical outcomes of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:536-544. |

| 12. | Dowson HM, Strauss D, Ng R, Mason R. The acute management and surgical reconstruction following failed esophagectomy in malignant disease of the esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:135-140. |

| 13. | Horstmann O, Verreet PR, Becker H, Ohmann C, Röher HD. Transhiatal oesophagectomy compared with transthoracic resection and systematic lymphadenectomy for the treatment of oesophageal cancer. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:557-567. |

| 14. | Chu KM, Law SY, Fok M, Wong J. A prospective randomized comparison of transhiatal and transthoracic resection for lower-third esophageal carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1997;174:320-324. |

| 15. | Orringer MB, Marshall B, Iannettoni MD. Eliminating the cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leak with a side-to-side stapled anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:277-288. |

| 16. | Korst RJ, Port JL, Lee PC, Altorki NK. Intrathoracic manifestations of cervical anastomotic leaks after transthoracic esophagectomy for carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:1185-1190. |

| 17. | Tinoco RC, Tinoco AC, El-Kadre LJ, Rios RA, Sueth DM, Pena FM. [Laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy: outcomes]. Arq Gastroenterol. 2007;44:141-144. |

| 18. | Hölscher AH, Schneider PM, Gutschow C, Schröder W. Laparoscopic ischemic conditioning of the stomach for esophageal replacement. Ann Surg. 2007;245:241-246. |

| 19. | Honkoop P, Siersema PD, Tilanus HW, Stassen LP, Hop WC, van Blankenstein M. Benign anastomotic strictures after transhiatal esophagectomy and cervical esophagogastrostomy: risk factors and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:1141-1146; discussion 1147-1148. |

| 20. | Dewar L, Gelfand G, Finley RJ, Evans K, Inculet R, Nelems B. Factors affecting cervical anastomotic leak and stricture formation following esophagogastrectomy and gastric tube interposition. Am J Surg. 1992;163:484-489. |

| 21. | Haight C. Congenital atresia of the esophagus with tracheoesophageal fistula: Reconstruction of esophageal continuity by primary anastomosis. Ann Surg. 1944;120:623-652. |

| 22. | Szücs G, Tóth I, Gyáni K, Kiss JI. Telescopic esophageal anastomosis: operative technique, clinical experiences. Dis Esophagus. 2003;16:315-322. |

| 23. | Henriques AC, Pezzolo S, Faure MG, da Luz LT, Godinho CA, Speranzini MB. Gastro-esophageal isoperistaltic bypass as palliative treatment of the irresectable esophageal cancer. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2001;28:408-413. |

| 24. | Thompson SK, Ruszkiewicz AR, Jamieson GG, Esterman A, Watson DI, Wijnhoven BP, Lamb PJ, Devitt PG. Improving the accuracy of TNM staging in esophageal cancer: a pathological review of resected specimens. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3447-3458. |

| 25. | Roth JA, Putnam JB Jr. Surgery for cancer of the esophagus. Semin Oncol. 1994;21:453-461. |

| 26. | Griffin SM, Shaw IH, Dresner SM. Early complications after Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy: risk factors and management. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:285-297. |

| 27. | Stilidi I, Davydov M, Bokhyan V, Suleymanov E. Subtotal esophagectomy with extended 2-field lymph node dissection for thoracic esophageal cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:415-420. |

| 28. | Chung SC, Stuart RC, Li AK. Surgical therapy for squamous-cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. Lancet. 1994;343:521-524. |

| 29. | Tirnaksiz MB, Deschamps C, Allen MS, Johnson DC, Pairolero PC. Effectiveness of screening aqueous contrast swallow in detecting clinically significant anastomotic leaks after esophagectomy. Eur Surg Res. 2005;37:123-128. |