Published online Nov 14, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i42.5391

Revised: July 28, 2010

Accepted: August 4, 2010

Published online: November 14, 2010

A 62-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital due to severe chest pain, odynophagia, and hematemesis. Chest computed tomography showed an esophageal submucosal tumor. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a longitudinal purplish bulging tumor of the esophagus. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) showed a mixed echoic tumor with partial liquefaction from the submucosal layer. The patient was diagnosed with esophageal intramural hematoma as well as achalasia by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, esophagography and esophageal manometry. The patient was managed conservatively with intravenous nutrition, and oral feeding was discontinued. Follow-up EGD and EUS showed complete recovery of the esophageal wall, and finally, the patient underwent endoscopic dilatation for achalasia. The patient was symptom free at the time when we wrote this manuscript.

- Citation: Chu YY, Sung KF, Ng SC, Cheng HT, Chiu CT. Achalasia combined with esophageal intramural hematoma: Case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(42): 5391-5394

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i42/5391.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i42.5391

Esophageal intramural hematoma (EIH) is an uncommon cause of severe chest pain. More than 63% of patients with EIH have an underlying etiology or predisposing factors such as esophageal instrumentation, vomiting, trauma, pill-induced injury, food impaction-related issue, or coagulation defects[1]. We report a patient with severe chest pain, dysphagia, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding who was subsequently diagnosed with EIH and achalasia. The patient was initially diagnosed by esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and underwent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for further confirmation. After conservative treatment, the patient recovered well and then underwent esophageal manometric examination and a series of EGD and EUS follow-up.

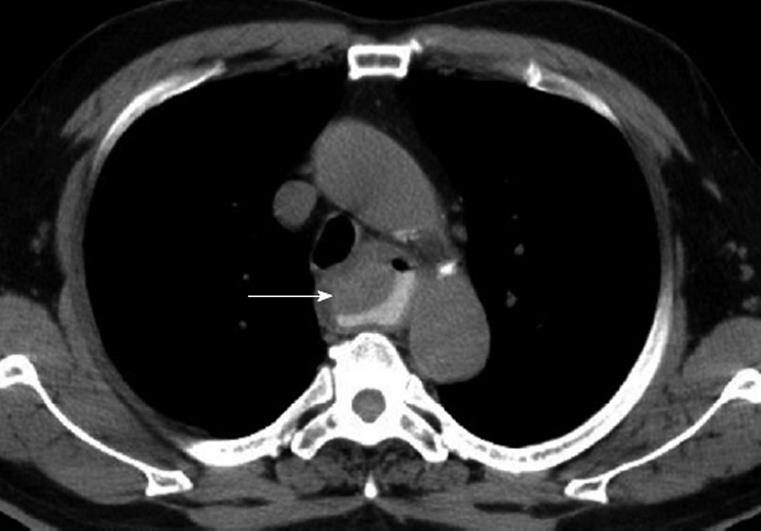

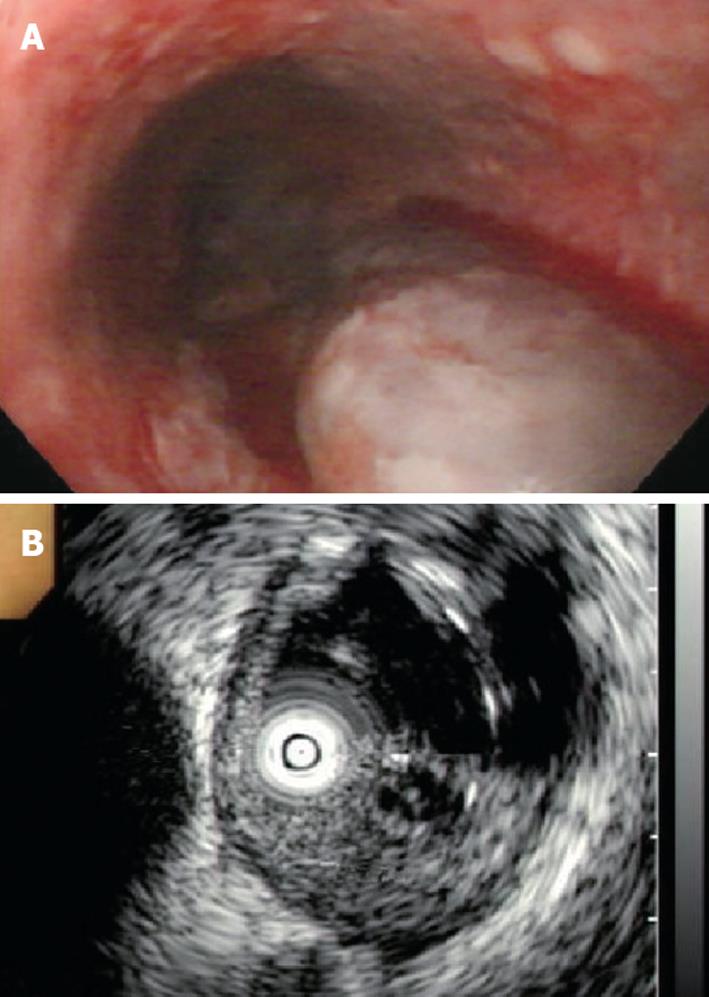

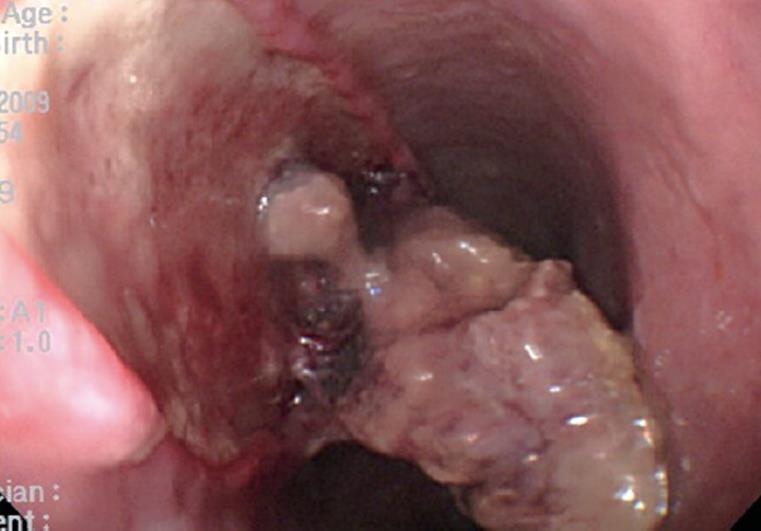

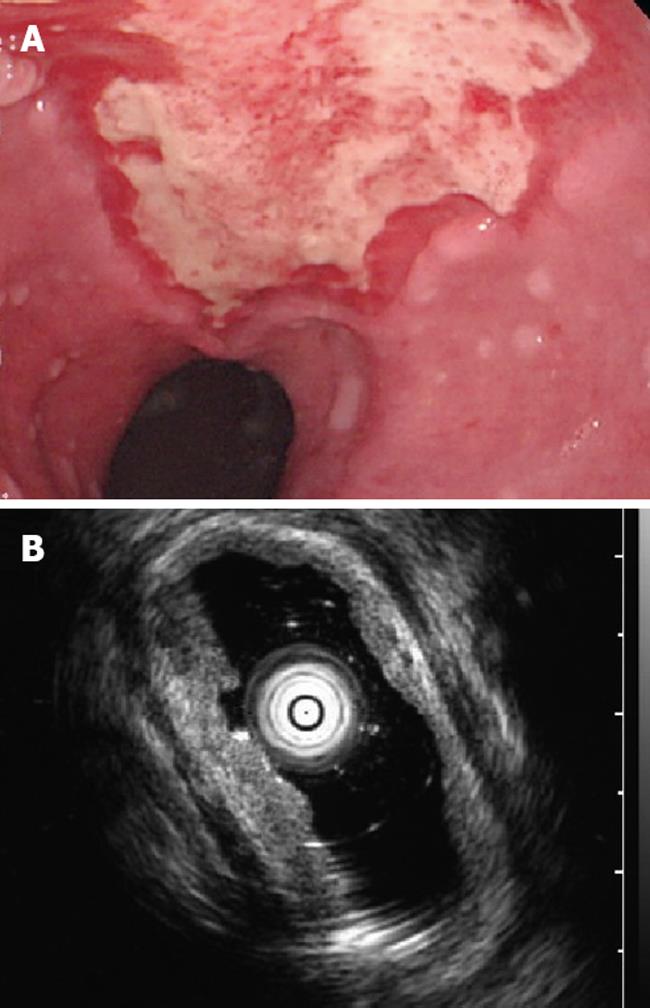

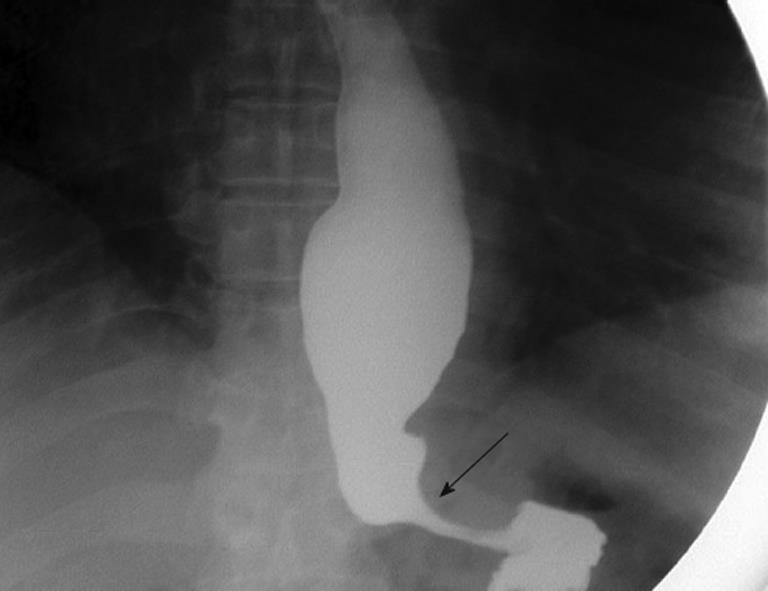

A 62-year-old male patient had a history of hypertension which was treated with regular calcium channel antagonists. He suffered from dysphagia, intermittent anterior chest pain, and poor oral intake for 1 mo but no nausea or vomiting, no acid or food regurgitation, and no significant body weight loss. He did not seek medical aid until he experienced an episode of severe anterior chest pain, odynophagia, and hematemesis. He was sent to the emergency room. Laboratory results revealed a hemoglobin level of 13.5 g/dL and a platelet count of 205 000/mL. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia, and chest X-ray was normal. Chest computed tomography revealed a slight hyperdense tumor with a smooth surface over the upper thoracic esophagus anterior wall extending to the subcarina area with no evidence of aortic dissection (Figure 1). He then received EGD which revealed a longitudinal oozing purplish, bulging tumor from the upper to mid-esophagus. Differential diagnosis included metastatic malignancy, submucosal tumor, and hematoma. EUS showed a mixed echoic and partially liquefied mass lesion with irregular margins over the submucosal layer (Figure 2). Intramural hematoma of the esophagus was diagnosed based on these examinations. Two days after the patient was managed as nil by mouth, through use of intravenous nutrition and analgesics, he received a follow-up EGD, which revealed a dissected necrotic mass lesion with submucosal ulceration (Figure 3). Endoscopic biopsy was performed to exclude malignancy, and pathology showed necrosis and acute inflammation but no malignant cells. Follow-up EGD performed 1 wk later revealed complete resolution of the submucosal hematoma with longitudinal superficial ulcer, and EUS showed no mass lesions and only mild thickening of the mucosal and submucosal layer (Figure 4). The patient began to try liquid diet intake and was discharged on the 10th day after admission. One month later, during an outpatient visit, the patient still had dysphagia symptoms. EGD showed an intact esophageal mucosa with a tight esophagocardiac junction (ECJ) and residual food accumulation in the esophagus. Barium esophagography showed a normal esophageal wall contour but a dilated lumen with narrowing of the ECJ (Figure 5), and achalasia was suspected. The patient also received an esophageal manometric examination, which revealed 90% simultaneous contraction of the esophageal body, impaired relaxation of the low esophageal sphincter (LES) and LES pressure of 58 mm Hg. These findings were compatible with achalasia, so he received endoscopic dilatation twice for achalasia. After treatment, the patient returned to normal oral intake and symptom free during the 18-mo follow up.

EIH is a rare disease that was first described by Williams in 1957[2]. Most reported cases of EIH occurred in women. The age range of patients with EIH is 20-89 years, and most of the patients are in the seventh or eighth decade of life. It has been reported that EIH is associated with coagulopathy[3], variceal injection sclerotherapy[4], and endoscopic instrumentation or foreign body ingestion[5]. It has also been known to occur spontaneously in healthy people[6]. EIH usually presents as a sudden onset of chest pain followed by odynophagia, dysphagia, and mild hematemesis.

EUS examination of EIH is limited. In our case, initial EUS showed a mixed echoic tumor lesion with an anechoic component and a mild irregular surface involving the mucosal and submucosal layers, but the muscularis propria was preserved and partial organization of hematoma was preferred rather than solid tumor. This patient also underwent follow-up EUS 1 wk later, which showed thickening of the mucosal and submucosal layers with a mucosal defect compatible with ulcer and complete resolution of hematoma.

EIH occurs as a result of 2 types of trauma to the esophageal wall: barotrauma and direct trauma[7]. Esophageal barotrauma occurs due to a sudden increased transmural pressure associated with coughing, or retching. Direct trauma results from endoscopic injection sclerotherapy, or swallowing of pills or a large food bolus. Our patient was not known to have achalasia prior to this admission, possibly because he was symptom free due to long-term intake of calcium channel antagonists for controlling hypertension. He had intermittent chest pain and dysphagia for 1 mo. These symptoms may have been related to the underlying achalasia, but he denied having nausea, vomiting, or food regurgitation. However, he did experience a feeling of something being stuck in his esophagus. Furthermore, his platelet count and prothrombin time were normal, which prompted us to consider food bolus-related direct trauma to esophageal wall. To our knowledge, achalasia has been reported only in 4 female patients with EIH since 1957s[8-11] and three of them were already diagnosed with achalasia before the attack of EIH. Recurrent EIH has only been reported in 2 patients, with underlying achalasia[10,11] (Table 1). Fortunately, our patient fully recovered from EIH and underwent successful endoscopic dilatation for achalasia. He was in good condition, able to feed orally, and had no more chest pain or dysphagia at the time when we wrote this paper. However, long-term follow-up is needed.

| Authors | Age (yr) | Sex | Interval between the diagnosis of achalasia and EIH | Treatment of achalasia | EIH recurrence (Interval between recurrence) |

| Freeman et al[8] | 69 | F | 3 mo1 | Surgery | No |

| Herbetko et al[9] | 43 | F | 15 yr | Heller’s myotomy | No |

| McIntyre et al[10] | 48 | F | 8 yr | Medication | Yes (7 yr) |

| Hooper et al[11] | 45 | F | 19 yr | Heller’s myotomy | Yes (15 mo) |

The prognosis of patients with EIH is good, death has only been reported following thoracotomy for this condition[12]. Management should be conservative. Most patients can be treated using intravenous nutrition, analgesics with oral feeding discontinued. Bleeding from EIH is usually mild and spontaneously subsided, but sometimes if bleeding is severe, endoscopic hemostasis or angiography with embolization even surgical intervention is necessary.

In conclusion, EIH is a rare disease that has different predisposing factors. EGD is a safe procedure for initial diagnosis. EUS findings help differentiate intramural hematoma from a solid tumor, cyst, or vessel. A series of follow-up endoscopies can help understand the natural course of EIH. Management is conservative, and the outcome is excellent with almost full recovery. However, it should be kept in mind that recurrence has been reported especially in patients with underlying achalasia.

Peer reviewer: Shan Rajendra, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Launceston General Hospital, Launceston, Tasmania 7250, Australia

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Criblez D, Filippini L, Schoch O, Meier UR, Koelz HR. [Intramural rupture and intramural hematoma of the esophagus: 3 case reports and literature review]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1992;122:416-423. |

| 2. | Williams B. Case report; oesophageal laceration following remote trauma. Br J Radiol. 1957;30:666-668. |

| 3. | Kamphuis AG, Baur CH, Freling NJ. Intramural hematoma of the esophagus: appearance on magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;13:1037-1042. |

| 5. | Salomez D, Ponette E, Van Steenbergen W. Intramural hematoma of the esophagus after variceal sclerotherapy. Endoscopy. 1991;23:299-301. |

| 6. | Shay SS, Berendson RA, Johnson LF. Esophageal hematoma. Four new cases, a review, and proposed etiology. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:1019-1024. |

| 7. | Lauzon SC, Heitmiller RF. Transient esophageal obstruction in a young man: an intramural esophageal hematoma? Dis Esophagus. 2005;18:127-129. |

| 8. | Freeman AH, Dickinson RJ. Spontaneous intramural oesophageal haematoma. Clin Radiol. 1988;39:628-634. |

| 9. | Herbetko J, Brunton FJ. Oesophageal haematoma: report of three cases. Clin Radiol. 1988;39:462-463. |

| 10. | McIntyre AS, Ayres R, Atherton J, Spiller RC, Cockel R. Dissecting intramural haematoma of the oesophagus. QJM. 1998;91:701-705. |

| 11. | Hooper TL, Gholkar J, Smith SR, Manns JJ, Moussalli H. Recurrent sub-mucosal dissection of the oesophagus in association with achalasia. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:955-956. |