Published online Nov 14, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i42.5342

Revised: June 9, 2010

Accepted: June 16, 2010

Published online: November 14, 2010

AIM: To compare the therapeutic effects of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RA) on gastroduodenal ulcers under continuous use of low-dose aspirin.

METHODS: Sixty patients who had a gastroduodenal ulcer on screening endoscopy but required continuous use of low-dose aspirin were randomly assigned to receive PPI (lansoprazole 30 mg, n = 30) or H2RA (famotidine 40 mg or if famotidine had been administered before assignment, ranitidine 300 mg, n = 30). The therapeutic effects were evaluated by endoscopy after 8-wk treatment. The presence or absence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) was determined by urea breath test before treatment. Abdominal symptoms were compared with the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS) questionnaire before and after treatment.

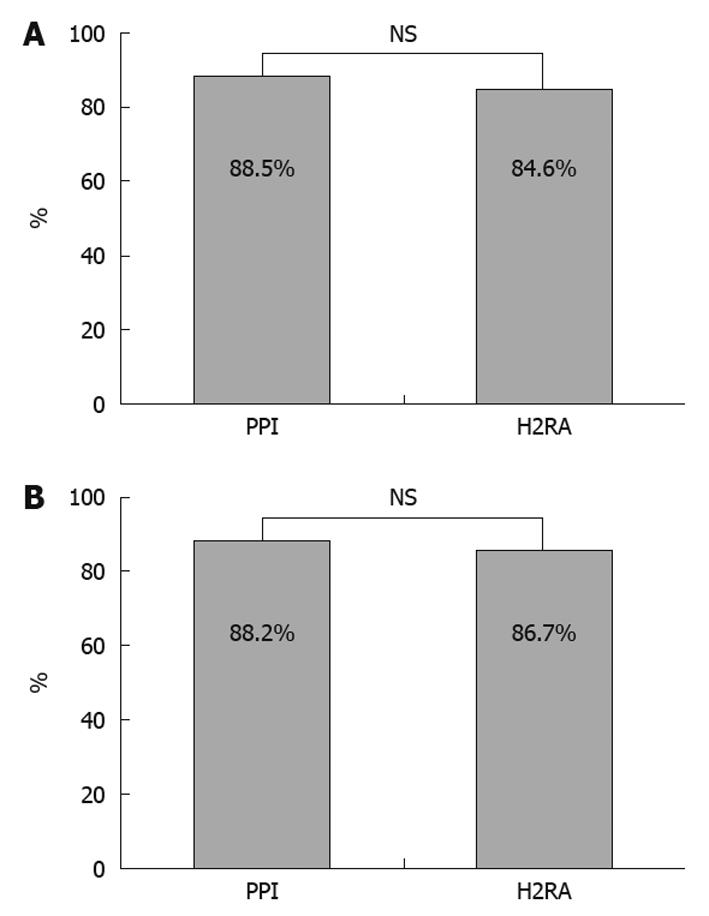

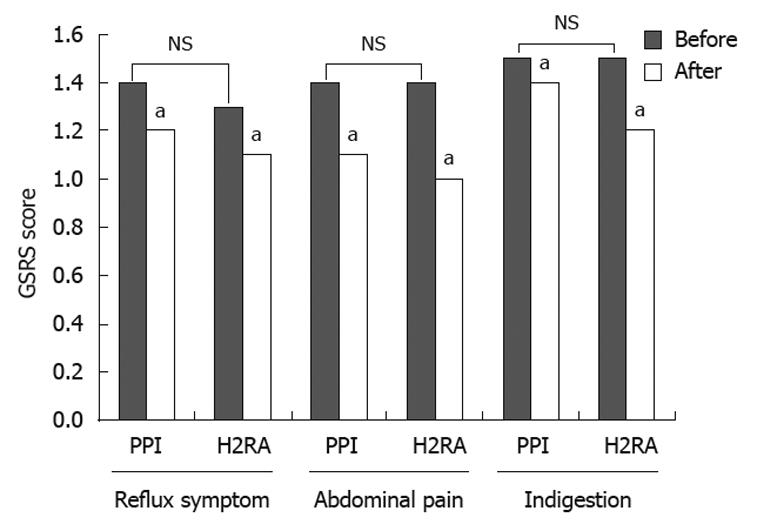

RESULTS: Twenty-six patients in the PPI group and 26 patients in the H2RA group, excluding dropouts, were analyzed. There were no significant differences in median age, sex, underlying disease, smoking status, H. pylori infection, prevalence of ulcers before treatment, and lesion site between the two groups. The therapeutic effects were endoscopically evaluated as healed in 23 patients (88.5%) and not healed in 3 patients in the PPI group and as healed in 22 patients (84.6%) and not healed in 4 patients in the H2RA group. Abdominal symptoms before treatment were uncommon in both groups; the GSRS scores were not significantly reduced after treatment as compared with before treatment.

CONCLUSION: The healing rate of gastroduodenal ulcers during continuous use of low-dose aspirin was greater than 80% in both the PPI group and the H2RA group, with no significant difference between the two groups.

- Citation: Nema H, Kato M. Comparative study of therapeutic effects of PPI and H2RA on ulcers during continuous aspirin therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(42): 5342-5346

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i42/5342.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i42.5342

As the population of Japan ages, the use of low-dose aspirin has increased to prevent cerebral and myocardial infarction. Many reports from Japan and overseas showing evidence that low-dose aspirin is useful for preventing thrombosis have been published. However, low-dose aspirin use raises concern about its adverse effects such as gastrointestinal mucosal injury[1,2]. Low-dose oral aspirin (300 mg or less) is reportedly associated with a 2.6- to 3.0-fold increased risk of ulcers[3] and a 1.59-fold increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding[4]. The prevalence of low-dose (200 mg or less) aspirin-associated gastroduodenal ulcers was 11.9% to 15.7% in Japanese patients treated for ischemic heart disease[5], and another case-control study has shown that low-dose aspirin is associated with a 5.5-fold increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding[6]. However, low-dose aspirin is administered for the purpose of secondary prevention of cardiovascular events, and because drug suspension due to gastrointestinal injury would increase the risk of thrombosis, it is frequently difficult to discontinue the use of low-dose aspirin. In fact, when long-term users of low-dose aspirin suspended the use of the drug, the risk of thrombosis increased[7,8]. Therefore, gastrointestinal injury should be treated under continuous use of low-dose aspirin. Previous studies from Western countries have shown that proton pump inhibitors (PPI) are first-line drugs for the treatment of gastrointestinal injury associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) including aspirin[9-11]. However, there are no prospective studies focusing on low-dose aspirin, nor are there studies from Japan where Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection rate is high.

We conducted a prospective, multicenter controlled study to compare the therapeutic effects of ordinary dose of PPI and histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RA) on gastroduodenal ulcers during continuous use of low-dose aspirin.

Two hundred twenty-nine low-dose aspirin users developed an endoscopy-proven gastrointestinal ulcer between May 2006 and November 2009 at the Hokkaido University Hospital and associated facilities. Out of these patients, 78 patients who did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded. Patients were excluded from the study if they had gastrointestinal bleeding as a complication, underwent gastrectomy, had a serious complication, had been taking non-aspirin NSAIDs regularly, or were under 20 years or over 80 years old. Patients who administered non-aspirin NSAIDs on an as-needed basis were included.

One hundred fifty-one patients were recruited to this study. All of them wished to continue taking low-dose aspirin and gastric acid secretion inhibitors, because they had no vascular events after aspirin therapy. However, the majority of patients rejected a second endoscopy after 8 wk. Finally, 60 patients who provided written informed consent and required continuous use of low-dose aspirin were entered into the study.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of each facility. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant in this study.

Enrolled patients were randomly assigned to the PPI group (lansoprazole 30 mg, n = 30) or the H2RA group (famotidine 40 mg, n = 30) by Central Registry via the Internet. If patients who had been treated with famotidine before randomization were assigned to the H2RA group, they were treated with ranitidine 300 mg instead.

The presence of H. pylori was determined by urea breath test before treatment. An exhaled-breath sample was collected 20 min after patients took 13C-urea 100 mg orally, and the cut-off value was set at Δ13C 2.5‰[12].

Therapeutic effects were based on endoscopic findings obtained at the end of 8 wk treatment. Endoscopy was performed before and after treatment by a single endoscopist at each facility using GIF-XQ 240 (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Mucosal defects were measured with biopsy forceps and an ulcer was defined as a mucosal defect when it was 3 mm or more in diameter. Photographs of lesions were taken before and after treatment and therapeutic effects were evaluated by a single physician. Complete disappearance of a mucosal defect was defined as healed, reduction of mucosal defect as reduced, no change in mucosal defect as unchanged, enlargement of mucosal defect as aggravated.

Patients were instructed to record abdominal symptoms using gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS) just before the first and the second endoscopic examinations. The GSRS scores were compared before and after treatment to evaluate the improvement of abdominal symptoms.

Endoscopic healing rate and self-improvement rate using GSRS were statistically determined by Wilcoxon test. The statistical software used was the SPPS 15.0. A level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Four patients in the PPI group and 4 patients in the H2RA group dropped out of the study because they refused to undergo endoscopy when their symptoms disappeared or they were moved to another hospital. Medication compliance rate was as high as 80% or more among patients excluding dropouts. Twenty-six patients in the PPI group and 26 in the H2RA group qualified for analysis.

Buffered aspirin tablets (Bufferin 81) and enteric coated tablets (Bayaspirin 100) were continuously used by 11 and 15 patients, respectively, in the PPI group and by 10 and 16 patients, respectively, in the H2RA group. Two patients in each group had used NSAIDs as needed for headache (diclofenac sodium in 3 patients and zaltoprofen in 1 patient). H2RA had been used before enrollment in 3 patients in the PPI group (usual dose of ranitidine, usual dose of nizatidine, and half dose of famotidine respectively) and in 4 patients in the H2RA group (usual dose of famotidine, usual dose of ranitidine, usual dose of nizatidine, and half dose of nizatidine respectively). No patients had used PPI before enrollment. If patients assigned to the H2RA group had a history of famotidine use, they were administered ranitidine 300 mg.

There were no significant differences in median age, sex, underlying disease, smoking status, H. pylori infection, prevalence of ulcers before treatment, or lesion site between the PPI group and the H2RA group (Table 1).

| PPI group (n = 26) | H2RA group (n = 26) | P value | |

| Median age (yr) | 67.2 ± 8.7 | 71.1 ± 6.9 | NS |

| Male | 19 (73.1) | 19 (73.1) | NS |

| Ischemic heart disease | 15 (57.7) | 13 (50.0) | NS |

| Smoking | 11 (42.3) | 8 (30.8) | NS |

| Helicobacter pylori (+) | 13 (50.0) | 12 (46.2) | NS |

| Ulcer size > 5 mm | 13 (50.0) | 12 (46.2) | NS |

| Location of mucosal defect | |||

| Stomach | 24 | 23 | NS |

| Duodenal | 2 | 3 | |

| Aspirin | |||

| Buffered | 10 | 10 | NS |

| Enteric-coated | 16 | 16 | |

The therapeutic effects were endoscopically evaluated as healed in 23 of 26 patients in the PPI group and in 22 of 26 patients in the H2RA group, with no significant difference between the groups (Figure 1A).

Three patients in the PPI group were evaluated as not healed, including 2 evaluated as reduced and 1 evaluated as unchanged. In the 2 patients evaluated as reduced, multiple ulcers were observed at the antrum of the stomach and ulcers 10 and 5 mm in maximum diameter were reduced to 3 and 2 mm, respectively, after treatment. In the patient evaluated as unchanged, the use of 100 mg aspirin enteric coated tablets was continued for the treatment of angina pectoris, endoscopy revealed a solitary ulcer 5 mm in diameter at the body of the stomach, and there was no evidence of H. pylori infection.

Four patients in the H2RA group were evaluated as not healed, including 3 evaluated as reduced and 1 evaluated as unchanged. In the 3 patients evaluated as reduced, solitary ulcers 15 mm at the antrum of the stomach, 15 mm at the body of the stomach, and 3 mm at the antrum of the stomach were all reduced to 2 mm after treatment. In the patient evaluated as unchanged, the use of 162 mg buffered aspirin tablets was continued for the treatment of old myocardial infarction, multiple ulcers were observed at the antrum of the stomach 3 mm in maximum diameter on endoscopy, there was no evidence of H. pylori infection, diclofenac sodium was prescribed as needed, and usual dose of ranitidine had been administered before assignment to treatment group.

Improvement of abdominal symptoms was evaluated after treatment by comparing the GSRS scores before and after treatment. Pretreatment scores indicated that abdominal symptoms were uncommon in both the PPI group and the H2RA group. The scores were not significantly reduced after treatment as compared with before treatment in either group (Figure 2). No side events were observed in either group.

For research about influence of acid secretion, both groups were subdivided into 2 groups based on whether the patient had pangastritis or not. There were 17 patients in the PPI group with pangastritis and 15 in the H2RA group. The therapeutic effects were not significantly different between the non-pangastritis groups (Figure 1B).

One of the major adverse events associated with low-dose aspirin is gastrointestinal bleeding. However, screening endoscopy is widely used in Japan and peptic lesions are frequently pointed out on screening endoscopy before the development of overt gastrointestinal bleeding. Therefore, the subjects of this study were those found to have gastroduodenal lesions on endoscopy without gastrointestinal bleeding as a complication.

Low-dose aspirin-induced mucosal defect is commonly 5 mm or less[3]. Considering that lesions 5 mm or less in size can cause bleeding, and if left untreated, may be enlarged, we believe that small ulcers should be treated. Thus, patients with ulcers 3 mm or more were included in this study.

Controlled studies of the therapeutic effects of PPI vs H2RA for NSAIDs-associated gastric ulcers have shown that the healing rate after 8 wk treatment was significantly higher in the PPI group than in the H2RA group[9-11].

A recent controlled study investigated the preventative effects of PPI vs H2RA on the occurrence of bleeding ulcers associated with low-dose aspirin in patients not infected with H. pylori and concluded that PPI are significantly more effective than H2RA in preventing the occurrence of bleeding ulcers and abdominal symptoms[13]. However, the results of their preventative effects against ulcers cannot be extrapolated to the healing of ulcers. On the other hand, it was reported that patients who take H2RA with low-dose aspirin had fewer peptic ulcers than patients who take placebo[14].

In the present study, the healing rate of gastroduodenal ulcers associated with low-dose aspirin was similar in the PPI group and the H2RA group. This may be explained by the facts that half of the subjects included in this study were infected with H. pylori, the subjects were limited to the Japanese, and they had a lower ability to secrete gastric acid. Previous studies involving patients with duodenal ulcers have shown that average maximum gastric acid secretion was 21.9 mEq/h for Japanese men and 43.2 mEq/mL for American men[15,16]. However, a retrospective study from Western countries investigated the effects of H2RA (famotidine 20-40 mg or ranitidine 150-300 mg) and PPI (omeprazole 20 mg) on lowering the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in low-dose aspirin users and concluded that both drug classes have similar effects on preventing bleeding[17]. Further studies are needed to evaluate the therapeutic effects of both PPI and H2RA on low-dose aspirin-induced ulcers.

One patient evaluated as unchanged in the H2RA group developed an ulcer 3 mm in diameter, was not infected with H. pylori, and had a history of diclofenac sodium on an as-needed basis. One other patient in the PPI group had used diclofenac sodium as needed before assignment, but the ulcer was healed after 8 wk treatment. PPI are also reported to be effective when combined with low-dose aspirin and NSAIDs[18]. The combined use of low-dose aspirin and NSAIDs is known to be associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding[3]. When low-dose aspirin is used alone, H2RA is expected to heal ulcers, but it may be better to choose PPI in high risk cases in which low-dose aspirin and NSAIDs are combined. Even in these cases, PPI are considered to be more effective than H2RA for 4 wk treatment[11,18].

The patient evaluated as unchanged in the PPI group had an ulcer 5 mm in size and was not infected with H. pylori. This case indicated that some ulcers are not healed even when treated with PPI. Such cases require further investigation for their appropriate treatment.

In this study, none of the patients were treated with combined aspirin and other antiplatelet drugs. However, recently use of combinations of low-dose aspirin and other antiplatelet drugs (e.g. clopidogrel and ticlopidine) have been increased, especially after coronary bypass graft surgery. PPI decrease clopidogrel’s inhibitory effect on platelets[19]. It may be better to choose H2RA when low-dose aspirin and clopidogrel are combined. On the other hand, clopidogrel is not associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when used alone, but is associated with a 7.7-fold increased risk when used in combination with low-dose aspirin[20]. Further studies are required to investigate the preventive and therapeutic effects of PPI and H2RA on gastrointestinal events in the presence of combined aspirin and other antiplatelet drugs.

In conclusion, the healing rate of gastroduodenal ulcers was greater than 80% after 8-wk treatment with PPI or H2RA during continuous use of low-dose aspirin, with no significant difference between the two groups.

The use of aspirin has increased in the aging population. Aspirin increases the risk of gastrointestinal injury. The strategy to treat ulcers during low-dose aspirin treatment is not clear.

It was reported that proton pump inhibitors (PPI) are more effective than histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RA) in prevention of aspirin-induced ulcers.

In this study, the healing rate of aspirin-induced ulcers was greater than 80% in both the PPI and the H2RA groups, with no significant difference between groups.

This study may be useful for considering changes in treatment of aspirin-induced ulcer.

This article demonstrates some interesting points that compare the effects of PPI and H2-blocker in patients taking continuous low dose aspirin. The paper is well written, design is appropriate for end-points stated and patient number is nearly enough to draw conclusions.

Peer reviewers: Hoon Jai Chun, MD, PhD, AGAF, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Institute of Digestive Disease and Nutrition, Korea University College of Medicine, 126-1, Anam-dong 5-ga, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 136-705, South Korea; Dr. Mihaela Petrova, MD, PhD, Clinic of Gastroenterology, Medical Institute, Ministry of Interior, Sofia 1606, Bulgaria

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor O'Neill M E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | The Dutch TIA Trial Study Group. A comparison of two doses of aspirin (30 mg vs. 283 mg a day) in patients after a transient ischemic attack or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1261-1266. |

| 2. | Cryer B, Feldman M. Effects of very low dose daily, long-term aspirin therapy on gastric, duodenal, and rectal prostaglandin levels and on mucosal injury in healthy humans. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:17-25. |

| 3. | García Rodríguez LA, Hernández-Díaz S. Risk of uncomplicated peptic ulcer among users of aspirin and nonaspirin nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:23-31. |

| 4. | Derry S, Loke YK. Risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage with long term use of aspirin: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2000;321:1183-1187. |

| 5. | Nema H, Kato M, Katsurada T, Nozaki Y, Yotsukura A, Yoshida I, Sato K, Kawai Y, Takagi Y, Okusa T. Investigation of gastric and duodenal mucosal defects caused by low-dose aspirin in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:130-132. |

| 6. | Sakamoto C, Sugano K, Ota S, Sakaki N, Takahashi S, Yoshida Y, Tsukui T, Osawa H, Sakurai Y, Yoshino J. Case-control study on the association of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Japan. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:765-772. |

| 7. | Maulaz AB, Bezerra DC, Michel P, Bogousslavsky J. Effect of discontinuing aspirin therapy on the risk of brain ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1217-1220. |

| 8. | Ferrari E, Benhamou M, Cerboni P, Marcel B. Coronary syndromes following aspirin withdrawal: a special risk for late stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:456-459. |

| 9. | Yeomans ND, Tulassay Z, Juhász L, Rácz I, Howard JM, van Rensburg CJ, Swannell AJ, Hawkey CJ. A comparison of omeprazole with ranitidine for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Acid Suppression Trial: Ranitidine versus Omeprazole for NSAID-associated Ulcer Treatment (ASTRONAUT) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:719-726. |

| 10. | Agrawal NM, Campbell DR, Safdi MA, Lukasik NL, Huang B, Haber MM. Superiority of lansoprazole vs ranitidine in healing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastric ulcers: results of a double-blind, randomized, multicenter study. NSAID-Associated Gastric Ulcer Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1455-1461. |

| 11. | Campbell DR, Haber MM, Sheldon E, Collis C, Lukasik N, Huang B, Goldstein JL. Effect of H. pylori status on gastric ulcer healing in patients continuing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory therapy and receiving treatment with lansoprazole or ranitidine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2208-2214. |

| 12. | Ohara S, Kato M, Asaka M, Toyota T. Studies of 13C-urea breath test for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:6-13. |

| 13. | Ng FH, Wong SY, Lam KF, Chu WM, Chan P, Ling YH, Kng C, Yuen WC, Lau YK, Kwan A. Famotidine is inferior to pantoprazole in preventing recurrence of aspirin-related peptic ulcers or erosions. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:82-88. |

| 14. | Taha AS, McCloskey C, Prasad R, Bezlyak V. Famotidine for the prevention of peptic ulcers and oesophagitis in patients taking low-dose aspirin (FAMOUS): a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:119-125. |

| 15. | Tahir H, Sumii K, Haruma K, Tari A, Uemura N, Shimizu H, Sumioka M, Inaba Y, Kumamoto T, Matsumoto Y. A statistical evaluation on the age and sex distribution of basal serum gastrin and gastric acid secretion in subjects with or without peptic ulcer disease. Hiroshima J Med Sci. 1984;33:125-130. |

| 16. | Feldman M, Richardson CT, Lam SK, Samloff IM. Comparison of gastric acid secretion rates and serum pepsinogen I and II concentrations in Occidental and Oriental duodenal ulcer patients. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:630-635. |

| 17. | Lanas A, Bajador E, Serrano P, Fuentes J, Carreño S, Guardia J, Sanz M, Montoro M, Sáinz R. Nitrovasodilators, low-dose aspirin, other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:834-839. |

| 18. | Goldstein JL, Johanson JF, Hawkey CJ, Suchower LJ, Brown KA. Clinical trial: healing of NSAID-associated gastric ulcers in patients continuing NSAID therapy - a randomized study comparing ranitidine with esomeprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1101-1111. |

| 19. | Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, Le Gal G, Lacut K, Le Calvez G, Mansourati J, Mottier D, Abgrall JF, Boschat J. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole CLopidogrel Aspirin) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:256-260. |