INTRODUCTION

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a disease in which excessive fat accumulates in the liver of a patient without a history of alcohol abuse. There are two types of NAFLD: simple steatosis, demonstrating only fat deposition in hepatocytes, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), demonstrating not only steatosis but also a necro-inflammatory reaction. NASH can progress to liver cirrhosis and result in complications that include hepatocellular carcinoma[1]. NAFLD/NASH is recognized as a hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome[2], and elements of metabolic syndrome, such as central obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hypertriglyceridemia, are well-known risk factors for NAFLD[3-5].

In recent years, pediatric NAFLD has increased in line with the increased prevalence of pediatric obesity and has become an important worldwide health problem. Pediatric NAFLD has different histological characteristics from those of adult NAFLD[6]. In this article, we outline the epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, histological features, and treatment of pediatric NAFLD.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Approximately 20% of adults are estimated to have NAFLD, and 2%-3% of adults have NASH[7]. On the other hand, in children and adolescents, researchers from America[8] and Asia[9,10] estimate that the prevalence of NAFLD is 2.6%-9.6%. These data, however, must be interpreted carefully because the diagnostic criteria of NAFLD adopted in these studies are diverse and the accurate diagnosis of NAFLD and NASH requires histological evaluation, which is impossible to obtain for all subjects in population-based studies. Studies from Europe[11-13], Asia[14-16], and America[8] estimate that the prevalence of NAFLD among overweight or obese children and adolescents is 24%-77%. Despite the diversity of diagnostic criteria used in these studies, obesity is thought to be an important risk factor for pediatric NAFLD.

NAFLD is consistently more prevalent in boys than in girls[17] suggesting that sex hormones are associated with the occurrence of pediatric NAFLD. NAFLD is more prevalent in adolescents than in younger children[8] and sex hormones and insulin resistance in puberty may be the cause of this. The rate of NAFLD in African American children is lower than in Hispanic and Caucasian children, despite African American children being prone to having risk factors for NAFLD, such as obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes[17].

PATHOGENESIS

The “two-hit” hypothesis proposed by Day et al[18] is widely accepted as the pathogenesis of NAFLD/NASH; the first hit causes fat accumulation in hepatocytes, and the second hit causes inflammation and fibrosis. Fat accumulation in the liver is closely associated with metabolic derangements that are related to central obesity and insulin resistance. Fat accumulation can be caused by the increased delivery of free fatty acids to the liver, disordered metabolism of fatty acids by hepatocytes, or increased de novo synthesis of fatty acids and triglycerides[19-21].

Oxidative stress is thought to play an important role in the second hit by causing peroxidation of lipids that accumulate in hepatocytes. The cause of oxidative stress is the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by induction of CYP 2E1 in the liver, mitochondrial dysfunction, and so on[22,23]. Peroxidation of lipids causes mitochondrial dysfunction and results in the overproduction of ROS, thus forming a vicious cycle[24-27]. The immune response toward lipid peroxidation products has been associated with the progression of NAFLD[28]. Other changes that can mediate liver inflammation include an increase in inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α and a decrease in anti-inflammatory cytokines such as adiponectin[2,29].

DIAGNOSIS

To diagnose NAFLD, the exclusion of other liver diseases such as hepatitis B and C, autoimmune hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury, Wilson’s disease, and α1-antitrypsin deficiency is necessary. Pediatric NAFLD is often asymptomatic; however, patients may occasionally complain of abdominal pain, fatigue, or malaise[30-32]. Hepatomegaly is often observed on physical examination, although this finding may be missed in clinical practice[33]. Acanthosis nigricans (black pigmentation at skin folds or axillae that is associated with hyperinsulinemia) has been reported in up to 50% of pediatric NASH cases[30,34]. A family history of NAFLD should be referred to because familial clustering is often detected[35]. Increased serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) are predictors of the existence of NAFLD/NASH; however, normal serum levels of these aminotransferases do not exclude the existence of NAFLD/NASH. Although an elevated ALT and/or an enlarged echogenic liver, as revealed by ultrasonography, in the setting of overweight or obesity and/or evidence of insulin resistance are highly suggestive of NAFLD, histological evaluation remains the only means of accurately assessing the degree of steatosis, necro-inflammatory change, and fibrosis found in NASH and in distinguishing NASH from simple steatosis[36]. In addition, liver biopsy is useful in differentiating NAFLD from other liver diseases. Because pediatric NAFLD has different histological characteristics compared to adult NAFLD, careful histological evaluation is necessary.

Liver biopsy is regarded as the gold standard for the diagnosis of NAFLD/NASH; however, this procedure has some problems, such as high risk, high cost, and sampling error. Therefore, it is necessary to develop improved noninvasive methods for accurate screening and diagnosis. Currently, ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the imaging modalities generally used for the evaluation of hepatic steatosis. Although ultrasonography has some merits such as widespread availability, lack of radiation, and relatively low cost, it also has some demerits such as operator dependence, subjectivity in interpretation, unclear images in severely obese patients, and inability to detect mild hepatic steatosis. CT is not favored for use in children because it uses ionizing radiation. MRI appears to be a more accurate and reproducible method[37]. In addition, because MRI is not subject to interpretation or interobserver variation, it may be better than ultrasound for quantifying hepatic fat in children[38-40]. However, neither CT nor MRI can judge low-grade fibrosis. Ultrasound elastography and magnetic resonance elastography have been developed as modalities to measure liver stiffness which is a surrogate marker of liver fibrosis. Investigations are needed to determine the usefulness of these modalities in diagnosing pediatric NAFLD.

HISTOLOGY

The histological characteristics of pediatric NAFLD/NASH differ from those of adult NAFLD/NASH. Schwimmer et al[6] examined the histological appearance of 100 pediatric NAFLD cases and identified two different types of steatohepatitis. Type 1 NASH was consistent with NASH as described in adults and was characterized by steatosis, ballooning degeneration, and/or perisinusoidal fibrosis in the absence of portal changes. Type 2 NASH was a peculiar histological pattern in children and was characterized by steatosis, portal inflammation, and/or portal fibrosis in the absence of ballooning degeneration and perisinusoidal fibrosis. Type 1 NASH was reported to be present in only 17% of pediatric NAFLD, whereas type 2 NASH was present in 51%. Simple steatosis was present in 16% of subjects. Advanced fibrosis was present in 8% and liver cirrhosis was present in 3%. In cases of advanced fibrosis, the pattern was generally that of type 2 NASH. Children with type 2 NASH were significantly younger and had a greater severity of obesity than children with type 1 NASH. Boys were significantly more likely to have type 2 NASH and less likely to have type 1 NASH than girls. Type 2 NASH was more common in children of Asian, Native American, and Hispanic ethnicity. Type 1 and type 2 NASH may have a different pathogenesis, natural history, and response to treatment. It is currently unclear whether type 2 NASH changes to type 1 NASH as the patient ages.

Subsequently, Nobili et al[41] reported that type 1 NASH was present in only 2% of their 84 pediatric NAFLD subjects and type 2 NASH was present in 29%. The combination of both types was present in 52% of their pediatric NAFLD subjects, and simple steatosis was present in 17%. Accordingly, the overlap of type 1 and 2 was the most common pattern in their study. The discrepancy between the results of these studies may reflect the different ethnicity of subjects, which were mainly Hispanics and Asians in the study by Schwimmer et al[6] and were all Caucasians in the study by Nobili et al[41].

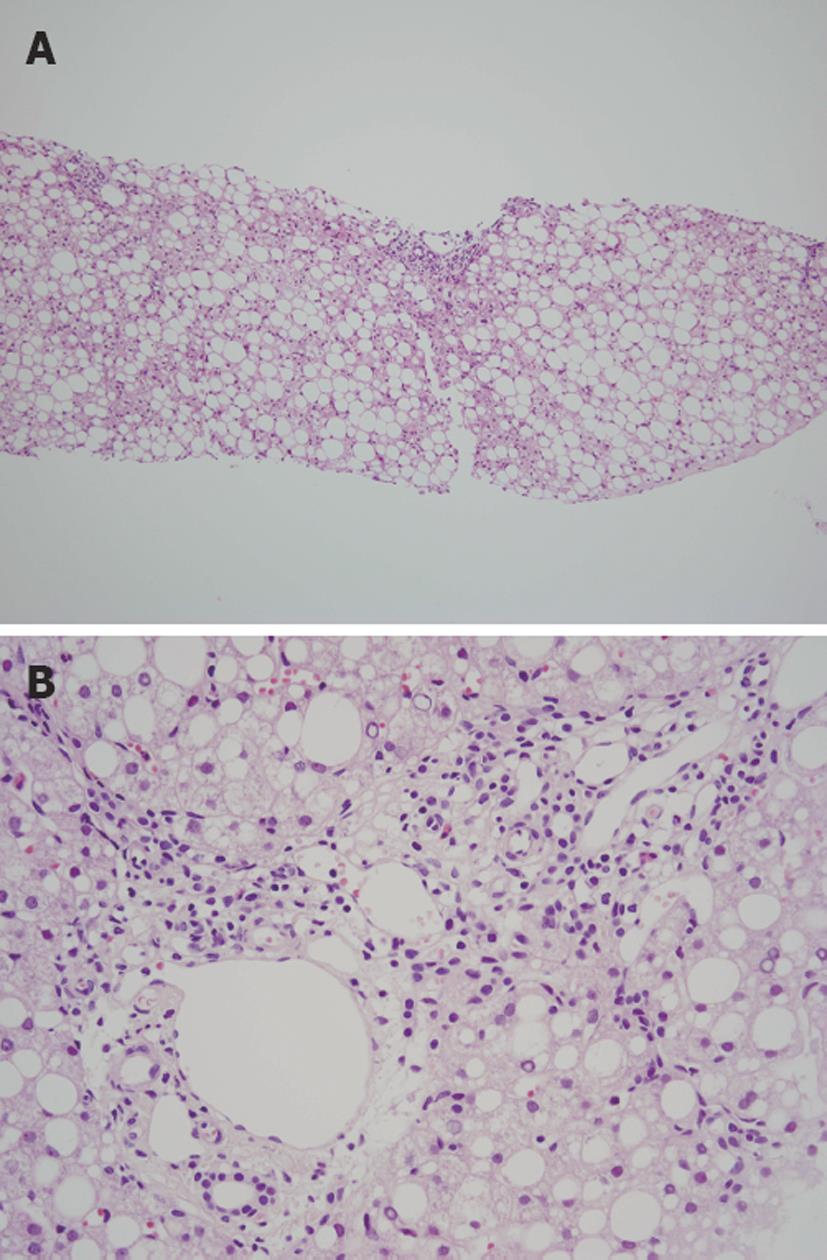

We compared the histological appearance of needle biopsy specimens from 34 pediatric and 23 adult NAFLD cases in Japan (unpublished data) and found that steatosis tended to be more severe in children as compared to adults (Figure 1A). Perisinusoidal fibrosis was significantly less frequent in children than in adults and intralobular inflammation and ballooning degeneration tended to be milder in children as compared to adults. Although portal inflammation tended to be more severe in children than in adults (Figure 1B), there was no obvious difference in the degree of portal fibrosis between the two groups. Type 2 NASH was present in 21% of pediatric subjects and in 9% of adult subjects. Accordingly, we confirmed that pediatric NAFLD had different histological characteristics from those of adult NAFLD in Japanese patients also. However, we found that the prevalence of type 2 NASH in pediatric subjects was less than that in the study by Schwimmer et al[6] and that the overlap of type 1 and 2 patterns was common as noted by Nobili et al[41].

Figure 1 Histological appearance of a case of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

A: Marked steatosis with panlobular distribution is observed (HE stain, × 40); B: Moderate inflammation is observed in the portal area (HE stain, × 200).

SPECULATED FACTORS THAT SEPARATE PEDIATRIC NAFLD AND ADULT NAFLD

The abovementioned histological differences between pediatric and adult NAFLD might reflect different etiological factors between them. In a study of morbidly obese adults undergoing bariatric surgery, portal inflammation was reported in 24%[42]. In a study of adult NAFLD subjects, which was composed of mainly male patients, portal inflammation and portal fibrosis were observed in 63% and 6% of patients, respectively[43]. Thus, it is conceivable that adult NAFLD patients, especially severely obese patients and male patients, may also show a pediatric-type histological pattern. As mentioned above, NAFLD is consistently more prevalent in boys than in girls[17], and type 2 NASH was more common in severely obese children and boys in the study by Schwimmer et al[6]. Accordingly, obesity and sex hormones might be critical etiological factors in pediatric NAFLD. In our histological investigation, steatosis tended to be more severe in pediatric NAFLD than in adult NAFLD, and its distribution was not restricted to zone 3 in many pediatric cases (unpublished data). Recently, we found that administration of fructose- or sucrose-enriched diet to Wistar rats induces hepatic steatosis that is mainly distributed in zone 1 (unpublished data). It is conceivable that inappropriate food consumption, especially excessive drinking of sweet beverages, might be an important cause of pediatric NAFLD; thus, the rat model might be a good model of pediatric NAFLD.

TREATMENT

Obesity, hyperlipemia, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia are well-known risk factors for NAFLD and oxidative stress is thought to be important in the progression from simple steatosis to NASH. Reducing the risk from these factors is considered to be an effective treatment for NAFLD. The main targets of therapy are normalization of the serum ALT level and improvement in histopathology as shown by biopsy. Lifestyle change (diet and exercise) and pharmacotherapy have been studied.

Diet and exercise

Most children with NAFLD are overweight or obese, and weight loss is thought to be an effective preventative measure and/or treatment for pediatric NAFLD. In fact, lifestyle modification remains the mainstay of treatment for NAFLD of obese children. Gradual weight loss by diet and proper exercise has been shown to improve serum aminotransferase levels and liver histology of adult patients with NAFLD[44-46]. In a study of pediatric NAFLD subjects, moderate weight loss by lifestyle intervention lowered serum aminotransferase levels and improved hepatic steatosis, lobular inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning; however, the degree of fibrosis did not change[47]. Based on the pathogenesis of NAFLD, an appropriate diet for NAFLD treatment is thought to be a low-glycemic index diet. Very rapid weight loss by excessive caloric restriction is not recommended because it may increase dysmetabolism and liver inflammation and fibrosis[48].

Vitamin E

Because oxidative stress plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of NASH, administration of antioxidants, such as vitamin E, is expected to be an effective therapy for NASH. In an open-label study, a 2-4 mo treatment with vitamin E (400-1200 IU/d orally) normalized serum aminotransferase levels in obese children with NASH but did not improve steatosis on ultrasonography, and serum aminotransferase returned to abnormal levels when the treatment was stopped[49].

Insulin sensitizers

Most children with NAFLD have insulin resistance, and therefore, insulin sensitizers may be an effective treatment for this disease. Metformin has been used successfully for improving insulin resistance and possibly liver histology in adults[50,51]. In addition, the efficacy and safety of metformin in the treatment of pediatric type 2 diabetes has been confirmed[52,53]. Open-label treatment with metformin for 24 wk showed notable improvement in liver chemistry, liver fat, insulin sensitivity, and quality of life in pediatric NASH patients[54]. Pioglitazone has been reported to improve biochemical and histological features of adult NASH[55,56]; however, data on the safety of pioglitazone in children are currently insufficient, and future investigations are needed in order to use this drug in pediatric NAFLD.

Ursodeoxycholic acid

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is a hydrophilic bile acid that operates as an antioxidative and cytoprotective agent. A randomized control trial (RCT) involving 31 obese children with abnormal serum aminotransferase levels, found that UDCA (10 mg/kg per day) was ineffective, both alone and when combined with diet, in reducing serum aminotransferases or the appearance of steatosis on ultrasonography[57]. Similarly, in two RCTs involving adult NAFLD/NASH, UDCA did not exert effects on liver chemistry or histology[58,59]. However, in one RCT, UDCA in combination with vitamin E improved serum aminotransferases and hepatic steatosis in NASH patients[60].

Bariatric surgery

In 2007, Furuya et al[61] examined the histological changes in the liver after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery performed in 18 severely obese NAFLD patients. As a result, steatosis disappeared in 84%, fibrosis disappeared in 75%, and hepatocellular ballooning disappeared in 50% of patients after 2 years. These improvements were likely a function of the substantial weight loss. Although the role of bariatric surgery for NAFLD in severely obese adolescents has not been studied, this treatment may be promising.

CONCLUSION

Pediatric NAFLD has been increasing worldwide and this tendency will continue as long as pediatric obesity increases. Liver biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of NAFLD; however, advances in noninvasive tests are expected. Pediatric NAFLD has different histological characteristics compared to adult NAFLD. Diet and exercise are the mainstays of treatment in NAFLD; however, advances in pharmacotherapy are expected.

Peer reviewer: Michel M Murr, MD, Professor of Surgery, USF Health, Director of Bariatric Surgery, Tampa General Hospital, 1 Tampa General Circle, Tampa, FL 33647, United States

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Lin YP