CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old male presented to the outpatient surgery clinic complaining of an enlarging mass on his left posterior shoulder, accompanied by increasing pain and decreased range of motion. He stated that the mass had grown from a small “pea sized” nodule to its current size within the last 6 mo. He denied any weight loss. His past medical and surgical histories were noncontributory. He reported a 40 pack-year history of tobacco use, but denied alcohol use or occupational chemical exposure. He denied any family history of malignancy.

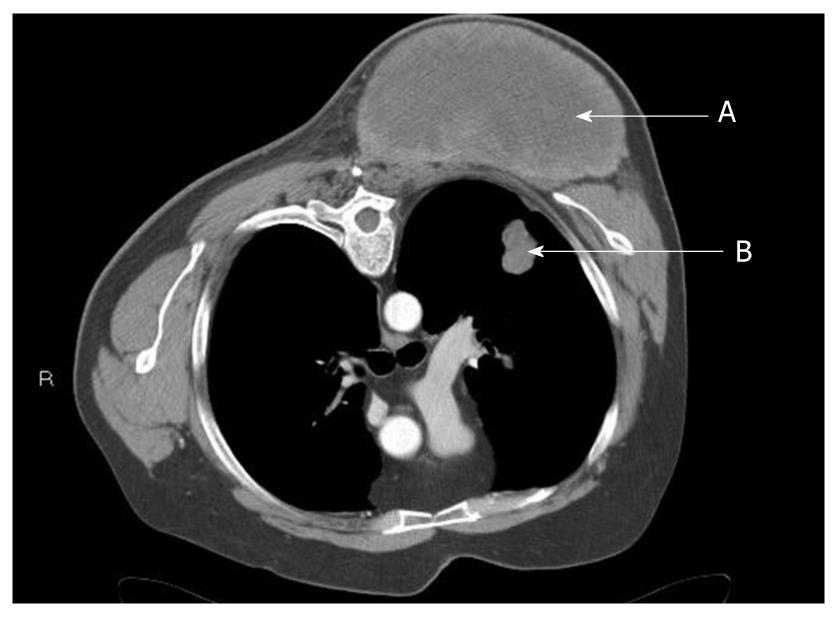

The physical examination was significant only for a firm, 10 cm × 20 cm mass on the left posterior shoulder, extending from the upper scapular border to the inferior tip, and from the left paraspinal muscles to the posterior axillary line (Figure 1). His range of motion was limited due to severe pain. Computed tomography (CT) performed several weeks prior to his surgical clinic evaluation demonstrated a 13.6 cm × 7.7 cm × 10 cm heterogeneous soft tissue mass located posterior to the left scapula, extending from the upper to the lower scapular borders, adjacent to or arising from the left paraspinous muscles (Figure 2). Rapid growth of the mass was apparent, but there was no evidence of bony involvement. Also noted was a 2.5 cm × 1.8 cm ill-defined nodule in the posterior left upper lobe of the lung (Figure 2), a 0.83 cm left perihilar nodule, and a sub centimeter peripheral density of the right posterior mid lung close to the pleura. Emphysematous changes and blebs were seen in the apices of the lungs bilaterally.

Figure 1 Large left shoulder mass.

Figure 2 Chest computed tomography scan showing mass of left posterior chest (A) and suspected left pulmonary metastasis (B).

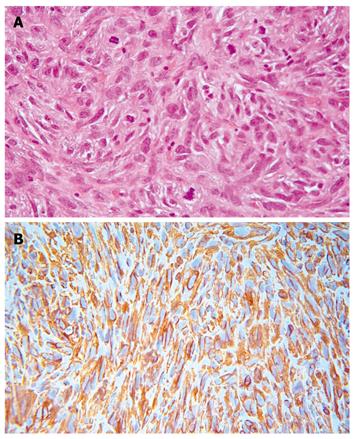

A diagnosis of sarcoma was suspected and subsequently confirmed by incisional biopsy, which revealed a grade 3 undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Microscopically the lesion was a highly cellular malignant mesenchymal neoplasm composed of large irregular, plump elongated to spindle shaped cells arranged in short fascicles with focal vague cartwheel and storiform patterns. The lesion was predominately diffuse and pleomorphic with no morphologic pattern or cytologic line of differentiation. The nuclei were large, crowded, and pleomorphic with shapes including vesicular, elongated, spindled and occasionally bizarre and multinucleate giant cells. More than 20 mitoses per 10 high power field were present (Figure 3A). The immunohistochemical reactivity showed 100% vimentin cytoplasmic reactivity (Figure 3B), 30% CD68 reactivity, 80% of nuclei showed MIB-1 reactivity and 50% of the sample exhibited necrosis. Immunohistochemical stains were nonreactive for epithelial, smooth muscle, striated muscle, neural, or lipoblast differentiation. The morphologic and immunohistochemical reactivity supported a diagnosis of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma grade 3.

Figure 3 High-grade pleomorphic sarcoma show large pleomorphic tumor cells in a fibrous stroma with numerous mitotic figures (A), tumor cells show a strong diffuse cytoplasmic immunoreactivity to vimentin (B).

Other immunoreactions failed to discern any line of differentiation. The “vimentin only” immunophenotype leads to a diagnosis of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.

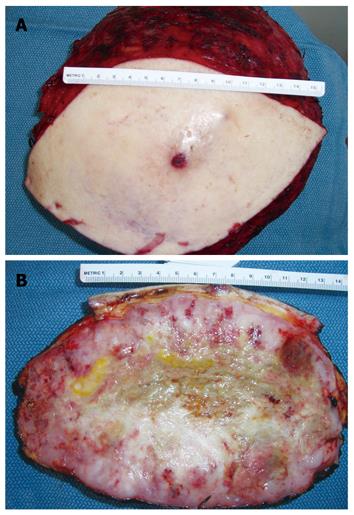

As metastasis to the lung was suspected, the patient was referred for cardiac and pulmonary evaluation in anticipation of a palliative resection with potential chest wall involvement. As part of the preoperative evaluation, the chest CT was repeated, revealing an increase in the primary tumor size compared to the prior CT, as well as multiple new lung nodules consistent with metastatic disease. After consulting with medical oncology, thoracic surgery and plastic surgery, the patient was offered a palliative resection of the mass due to severe pain and disability of his left shoulder. The resection involved removal of parts of the trapezius, latissimus dorsi, rhomboid, serratus posterior, paraspinal, and superficial scapular muscles. Using extensive undermining and creation of skin flaps, the wound was closed primarily over drains. The resected mass measured 23.0 cm × 24.0 cm × 12.0 cm and weighed 2730 g (Figure 4A and B) and the tumor involved the deep resection margin. Brachytherapy catheters were inserted in the wound adjacent to the chest wall. His immediate postoperative course was uncomplicated and he was discharged home on postoperative day seven.

Figure 4 Resected left shoulder mass (A), cross section of resected shoulder mass showing central necrosis and smooth glistening dense fish flesh like tumor at the periphery (B).

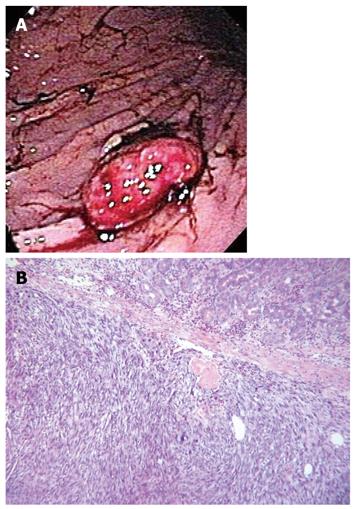

Two weeks after discharge, the patient presented for follow up complaining of burning upper abdominal pain and melanotic stools. Upper endoscopy was notable for mild diffuse gastritis and a 5 cm × 2 cm greater curvature mass (Figure 5A). The surface of the mass was ulcerated, hemorrhagic, with focal blood clots. The lesion was removed with snare and cautery with resolution of the bleeding. Biopsy revealed a grade 3 pleomorphic sarcoma consistent with metastatic disease (Figure 5B), as well as Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. He received blood transfusion due to severe anemia and treatment for the H. pylori infection. A few weeks later, while awaiting the initiation of chemotherapy the patient suffered a cerebrovascular accident and his condition deteriorated rapidly. He received only comfort care and was discharged to hospice.

Figure 5 Endoscopic view of the stomach shows a mass with surface ulceration and blood clots (A), the photomicrograph (B) reveals a malignant neoplasm, composed of densely cellular stroma with spindle cells containing pleomorphic nuclei.

DISCUSSION

Soft tissue sarcomas are unusual malignancies comprising 1% of cancers diagnosed in the United States[1]. Most primary sarcomas involve an extremity (59%); the next most common sites are trunk (19%), retroperitoneum (13%), and head and neck (9%)[2]. In a study of 1240 patients from the French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group, a multivariate analysis showed in the order of importance the following independent predictors for metastasis and survival: histologic grade, tumor size, bone or neurovascular involvement, and tumor depth for the overall group. The predictors for metastasis and survival for malignant fibrous histiocytoma were histologic grade and neurovascular or bone invasion[3]. In this study, the metastasis-free 5-year survival rate was 91% for grade 1, 71% for grade 2, and 44% for grade 3; this study along with others show that histologic grade is the most reliable predictor of metastatic risk and overall tumor-free survival in adult soft tissue sarcomas[3-5]. Several reported studies show that the quality of surgical margins is the most important factor for predicting local recurrence[3-7].

The most commonly used and critically analyzed histologic grading systems are the French grading[8,9] and the National Cancer Institute grading[10]. Both are 3-grade systems and are quoted in the latest edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of STS[11]. The National Cancer Institute system is based on tumor histologic type and subtype, location, and the amount of tumor necrosis. Cellularity, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic index are considered for some tumor types. The French grading system[8,9] is based on 3 components: tumor differentiation, mitotic index, and tumor necrosis. Tumor differentiation and mitotic index are scored 1 to 3 and necrosis 0 to 2. The 3-grade system is obtained by summing the scores for each of the components. Grade 1 is defined as a score of 3 or less; grade 2 has a score of 4 or 5; and grade 3 has a score of 6 to 8. A MIB-1 score, as recently used by Hasegawa et al[12] using the French grading system, could replace the mitotic index, which may be difficult to evaluate in small biopsies. These authors found that grading using the MIB-1 score was more reproducible, and it had a better predictive value than the classical grading using mitotic index[13].

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) accounts for approximately 20% of all adult soft tissue sarcomas[5], and occurs most commonly in the extremities, trunk or retroperitoneum[2]. The term MFH was introduced by Ozzello et al[14] and described by O’Brien et al[15], to describe a group of malignant mesenchymal lesions (sarcomas) which manifested features of both fibroblastic and histocytic differentiation. Kempson et al[16] further characterized the lesion as having a storiform growth pattern with varying proportions of histiocytes and giant cells. The origin and existence of the MFH as a distinct pathological entity is controversial. The current consensus is that the MFH, especially the pleomorphic storiform subtype, is a common “morphologic pattern” shared by a number of pleomorphic neoplasms, irrespective of their histologic origin and represents a “final common pathway” for tumor growth. Every effort must be employed to identify a line of differentiation in this group of lesions, and those neoplasms in which no line of differentiation can be identified are designated storiform-pleomorphic MFH. Therefore, storiform-pleomorphic MFH is a diagnosis of exclusion[17]. In such cases, the WHO classification of soft tissue tumors[11] advocates an alternate name undifferentiated high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma. After this conceptual shift, this subtype, which was considered to be the most common soft tissue tumor in adults now accounts for no more than 5% of adult soft tissue sarcomas[18].

The use of immunohistochemistry is essential in the diagnostic workup of any MFH-like tumor because a diagnosis based on morphology alone is unacceptable. Since the diagnosis of MFH is one of exclusion, an extensive immunohistochemistry panel is required to identify a definitive line of differentiation. The immunohistochemical marker panel must include broad markers such as vimentin and cytokeratins for mesenchymal and epithelial differentiation, respectively. The panel may then be narrowed to add specific markers related to the clinical setting and the histologic suspicion. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma typically demonstrates immunoreactivity to vimentin but fails to show immunoreactivity of other lines of differentiation. Traditional histocytic markers such as CD68, α1-antitrypsin, α1-antichymotrypsin, and factor XIII no longer play a useful role in the diagnosis of MFH. Immunoreactivity of these markers is found to be nonspecific and therefore, will not support a definitive diagnosis of MFH[19,20]. This lesion showed 100% cytoplasmic vimentin reactivity and the other markers were nonreactive or displayed insignificant reactivity.

There have been occasional reports of MFH occurring as primary malignancies in the stomach[4], however, metastatic MFH to the stomach is rare. The case presented here is the third case of a metastatic gastric MFH that presented with gastroduodenal bleeding. The other two cases were published in 1983 by Adams et al[21] and in 2009 by Karanlik et al[22]. A review of the literature yielded 10 cases of MFH with metastasis to the stomach[23]. Of the 10 reported cases of gastric metastasis, six were classified as storiform-pleomorphic. The case reported here is likewise of the storiform-pleomorphic subtype. Undifferentiated storiform-pleomorphic sarcoma as seen in our case presentation, accounts for approximately 5% of sarcomas occurring in adults. The most common sites of metastasis of pleomorphic sarcoma are the lung (80%) and lymph nodes (32%).

The pathologic characteristic of MFH is that of a spindle-cell sarcoma with no distinct line of differentiation and typically presents in adults over 40 years old. The proliferative activity in soft tissue sarcoma has been assessed with the monoclonal antibody MIB-1[10]. The MIB-1 index ranges from 1% to 85% and correlates with mitotic score and tumor grade. The MIB-1 index of this patient’s tumor was > 80%, which explains its rapid growth, large size, and widespread metastasis. Like most patients with large (> 5 cm), high-grade sarcomas, our patient had metastatic disease on presentation.

Soft tissue sarcomas metastasize via hematogenous spread. Of the 10 previously reported cases of gastric metastasis, eight were found to be metastatic to the antrum and greater curvature suggesting a hematogenous pathway through the gastroduodenal or gastroepiploic vessels[23]. Likewise, the patient reported here had metastasis to the greater curvature. Sixty percent (6/10) of the reported cases of gastric metastasis were treated with distal gastrectomy and only two of these patients survived more than two years. The average length of survival for the other 4 patients who underwent resection was 7 mo[23]. Gastric metastasis portends a grave prognosis with only 20% (2/10) of patients surviving more than 16 mo. Our patient was too debilitated to undergo gastric resection; however, it is unlikely that resection would have resulted in any clinical benefit. This patient was 60 years old and male, which is consistent with other cases of gastric metastasis for MFH in which the average age was 66 and 8/10 cases were men.

The management of high-grade sarcoma usually involves a multidisciplinary approach, including surgical resection, radiation therapy, and adjuvant chemotherapy. Therapy is hampered by the fact that 20% of patients with high-grade soft tissue sarcoma have pulmonary metastatic disease at the time of initial diagnosis[24]. The endoscopist should consider the possibility of gastric metastasis in patients with a history of sarcoma who present with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Nearly all patients who present with bleeding from gastric metastasis due to high-grade sarcomas have widespread disease at presentation, thus the role of surgery is limited. Surgical resection of gastric metastasis may be performed to control life-threatening bleeding, but most patients do not receive long-term benefit.