Published online Oct 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i40.5084

Revised: June 10, 2010

Accepted: June 17, 2010

Published online: October 28, 2010

AIM: To examine the long term survival of geriatric patients treated with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in Japan.

METHODS: We retrospectively included 46 Japanese community and tertiary hospitals to investigate 931 consecutive geriatric patients (≥ 65 years old) with swallowing difficulty and newly performed PEG between Jan 1st 2005 and Dec 31st 2008. We set death as an outcome and explored the associations among patient’s characteristics at PEG using log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazard models.

RESULTS: Nine hundred and thirty one patients were followed up for a median of 468 d. A total of 502 deaths were observed (mortality 53%). However, 99%, 95%, 88%, 75% and 66% of 931 patients survived more than 7, 30, 60 d, a half year and one year, respectively. In addition, 50% and 25% of the patients survived 753 and 1647 d, respectively. Eight deaths were considered as PEG-related, and were associated with lower serum albumin levels (P = 0.002). On the other hand, among 28 surviving patients (6.5%), PEG was removed. In a multivariate hazard model, older age [hazard ratio (HR), 1.02; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.00-1.03; P = 0.009], higher C-reactive protein (HR, 1.04; 95% CI: 1.01-1.07; P = 0.005), and higher blood urea nitrogen (HR, 1.01; 95% CI: 1.00-1.02; P = 0.003) were significant poor prognostic factors, whereas higher albumin (HR, 0.67; 95% CI: 0.52-0.85; P = 0.001), female gender (HR, 0.60; 95% CI: 0.48-0.75; P < 0.001) and no previous history of ischemic heart disease (HR, 0.69; 95% CI: 0.54-0.88, P = 0.003) were markedly better prognostic factors.

CONCLUSION: These results suggest that more than half of geriatric patients with PEG may survive longer than 2 years. The analysis elucidated prognostic factors.

- Citation: Suzuki Y, Tamez S, Murakami A, Taira A, Mizuhara A, Horiuchi A, Mihara C, Ako E, Muramatsu H, Okano H, Suenaga H, Jomoto K, Kobayashi J, Takifuji K, Akiyama K, Tahara K, Onishi K, Shimazaki M, Matsumoto M, Ijima M, Murakami M, Nakahori M, Kudo M, Maruyama M, Takahashi M, Washizawa N, Onozawa S, Goshi S, Yamashita S, Ono S, Imazato S, Nishiwaki S, Kitahara S, Endo T, Iiri T, Nagahama T, Hikichi T, Mikami T, Yamamoto T, Ogawa T, Ogawa T, Ohta T, Matsumoto T, Kura T, Kikuchi T, Iwase T, Tsuji T, Nishiguchi Y, Urashima M. Survival of geriatric patients after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in Japan. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(40): 5084-5091

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i40/5084.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i40.5084

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) was initially developed as an enteral nutrition technique by Gaudere et al[1] and Ponsky et al[2] in 1980. Since then, PEG has been widely used for patients with swallowing difficulty, because of reduced laryngopharyngeal discomfort and a lower risk of aspiration pneumonia compared with a nasogastric tube[3,4]. However, PEG feeding was found to be associated with an absolute increase in risk of death compared with nasogastric feeding[5]. In spite of the evidence, PEG has been widely used especially for geriatric patients with the increasingly aging society. Despite the very large number of patients receiving this intervention, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that PEG is beneficial for patients with swallowing difficulty arising from dementia or other chronic diseases[6,7]. Therefore, we conducted retrospective studies in multiple community hospitals in Japan to examine the long-term survival of geriatric patients treated with PEG and to delineate the factors associated with their mortality.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients who underwent PEG between 2005 Jan 1st and 2008 Dec 31st at 46 community hospitals all over Japan, selected by the panel of 103 doctor-experts in PEG and the trustees of the PEG Doctors’ Network as a non-profit organization. The study was approved by the institutional review board of each hospital. Doctors in charge of PEG in the selected hospitals were asked to examine 20 consecutive patients on whom a new PEG was performed, after excluding patients (1) whose age was ≤ 64 years old; (2) who had previously had a gastrectomy; (3) who had cancer considered to affect the patient’s prognosis; and (4) who had gastrostomy performed for reasons other than nutritional support. The doctors were further asked to report the number of excluded cases as well as the number of patients who were considered as lost to follow-up.

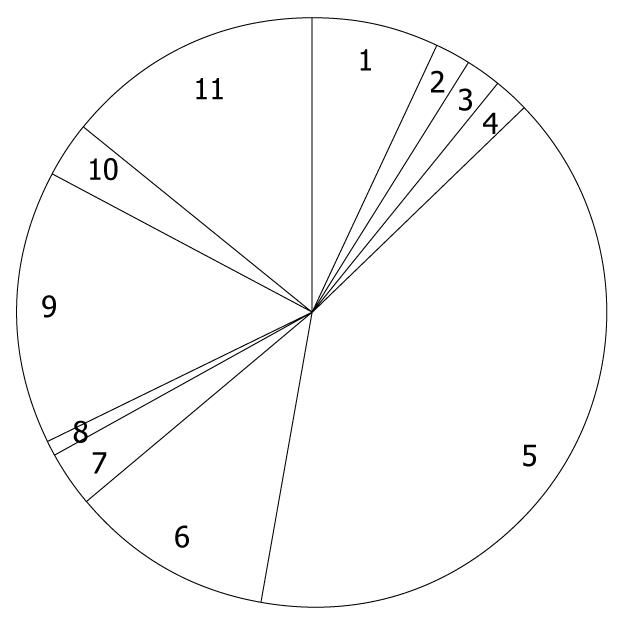

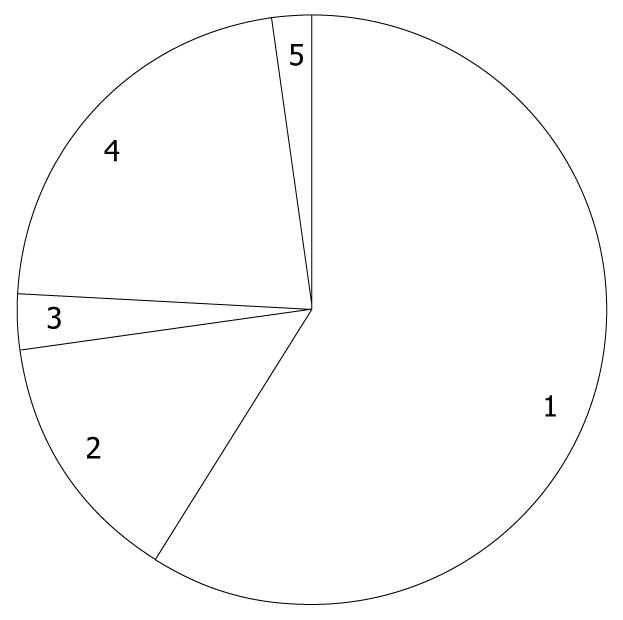

The primary outcome was set as death and the cut-off date was set at October 2009. In the case where the patient was alive, the doctor was further asked the status of the patient according to the following: (1) admission to this hospital, (2) admission in other hospital, (3) stay at nursing home, (4) stay at home, or (5) other. In case of loss to follow-up, the final date the patient was confirmed as alive was censured. Causes of death were selected from one from following: (1) primary diagnosis warranting PEG; (2) pneumonia; (3) cardiac failure; (4) cancer; (5) the PEG procedure; (6) other; and (7) unknown. The secondary endpoint was the removal of PEG because of improvement in the patient’s condition.

The following data were collected: (1) age; (2) gender; (3) height; (4) weight; (5) body temperature; (6) white blood cell (WBC)/μL; (7) hematocrit (Ht): %; (8) hemoglobin (Hb): g/dL; (9) aspartate aminotransferase (AST): IU/L; (10) alanine aminotransferase (ALT): IU/L; (11) blood urea nitrogen (BUN): mg/dL; (12) serum creatinine (Cr): mg/dL; (13) serum albumin: g/dL; (14) C-reactive protein (CRP): mg/dL; (15) previous history of pneumonia or ischemic heart disease; (16) comorbidity of dementia, diabetes, serious malnutrition judged by the doctor in charge; (17) starvation period before having PEG: none, within 1 wk, within 1 mo, more than 1 mo; and (18) primary diagnosis or underlying disease warranting PEG, selected from one of the following: (I) Neurological disease: (a) Parkinson’s disease; (b) amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; (c) multiple system atrophy; or (d) other neurological disease; (II) Cerebrovascular disease: (a) cerebral infarction; (b) cerebral hemorrhage; (c) subarachnoid hemorrhage; or (d) other cerebrovascular disease; (III) Dementia: (a) severe; (b) mild; or (c) other type of dementia; and (IV) Other disease, at the time of the PEG procedure, obtained from medical charts.

The Student t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were performed for continuous variables with normal and not normal distribution, respectively. Overall survival curves were drawn using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared for each variable using log-rank tests. The Cox proportional hazard models were fitted for multivariate analysis using variables significant in the log-rank tests and other tests. Adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were determined. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 11.0 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Of the 1168 patients who underwent PEG at the 46 selected hospitals, 237 were excluded from further analyses, having met at least one of the exclusion criteria, and thus 931 patients were followed and the median duration was 468 d, ranging from 1 to 1668 d. Among 931 patients, 122 patients were censored due to loss to follow-up at a median of 71 d, ranging from 6 to 1582 d. Mean age was 81.4 years old, ranging from 65 to 99 years. Females were predominant (54%). The distribution of primary diagnosis warranting PEG is shown in Figure 1, where cerebrovascular diseases accounted for more than half of the study population. In the previous history, pneumonia and ischemic heart disease were reported in 63% and 19% of patients, respectively. In addition, diabetes comorbidity was 18%. In total, 502 deaths were observed (mortality 53%), of which 10 deaths (2.0%) occurred within 7 d, 49 (9.8%) within 30 d, 105 (21%) within 60 d, 216 (43%) within 6 mo, and 287 (57%) within 1 year. Causes of death classified by the doctors are shown in Figure 2, and pneumonia was the major cause of death. Eight deaths were considered as PEG-related deaths, according to the reports of the doctors. On the other hand, among 28 surviving patients (6.5%), PEG was removed.

Continuous variables of demographic and laboratory data at PEG installation were first compared between alive and dead patients (Table 1). Age, CRP, AST, BUN and Cr were significantly higher in patients who died than in those who survived. In contrast, Ht, Hb and albumin were significantly higher in patients who survived than in patients who died. Regarding PEG-related death, albumin levels were significantly lower (Mann-Whitney U test: P = 0.002).

| Variable | Total (n = 931) | Alive (n = 429) | Dead (n = 502) | P-value |

| Age (yr) | 81.4 ± 7.8 | 80.0 ± 7.9 | 82.6 ± 7.6 | < 0.00011 |

| Height (cm) | 153.0 ± 10.4 | 152.4 ± 10.5 | 153.5 ± 10.2 | 0.201 |

| Weight (kg) | 44.7 ± 10.7 | 44.9 ± 10.8 | 44.6 ± 10.6 | 0.791 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 19.3 ± 3.7 | 19.5 ± 4.0 | 19.1 ± 3.6 | 0.221 |

| Body temperature (°C) | 36.7 ± 0.5 | 36.7 ± 0.5 | 36.7 ± 0.5 | 0.821 |

| White blood cell (/μL) 25/50/75 percentile | 5470/6770/8700 | 5500/6640/8570 | 5420/6800/8800 | 0.332 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) 25/50/75 percentile | 0.4/1.2/2.8 | 0.4/1.0/2.4 | 0.4/1.2/3.2 | 0.0162 |

| Hematocrit (%) 25/50/75 percentile | 29.8/33.5/37.1 | 30.9/34.2/37.7 | 29.2/32.8/36.6 | 0.00012 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) 25/50/75 percentile | 9.8/11.0/12.3 | 10.1/11.3/12.6 | 9.5/10.8/12.1 | 0.00012 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) 25/50/75 percentile | 18/24/35 | 18/23/31 | 18/24/39 | 0.0192 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) 25/50/75 percentile | 12/19/33 | 12/19/29 | 11/20/40 | 0.222 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) 25/50/75 percentile | 12.8/17.7/24.8 | 12.4/17.0/23.1 | 13.0/18.6/26.1 | 0.0182 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) 25/50/75 percentile | 0.42/0.59/0.80 | 0.40/0.56/0.76 | 0.44/0.60/0.81 | 0.00962 |

| Albumin (g/dL) 25/50/75 percentile | 2.6/3.0/3.3 | 2.7/3.0/3.4 | 2.6/2.9/3.2 | 0.00132 |

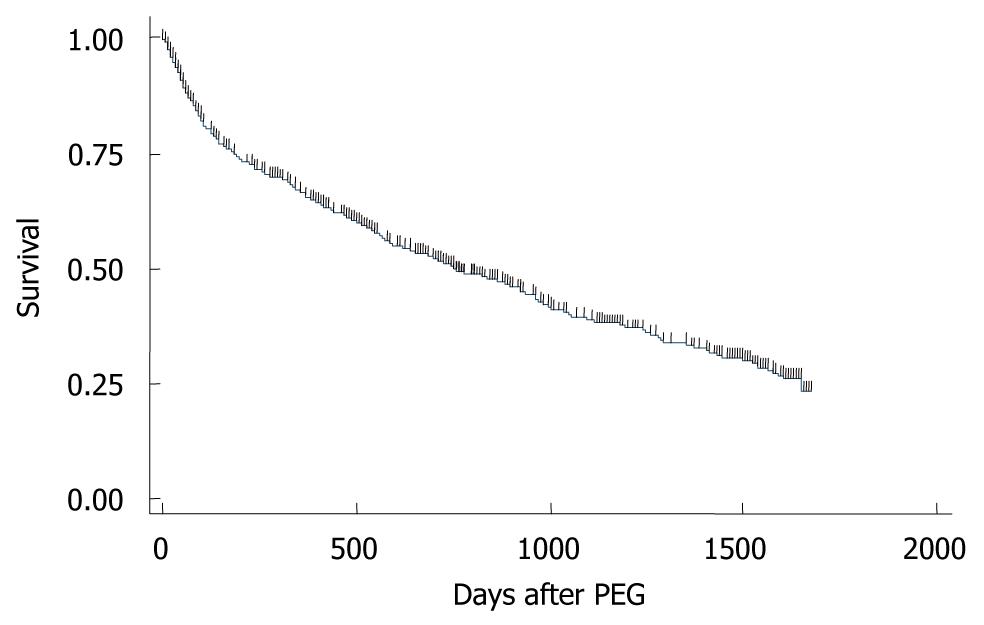

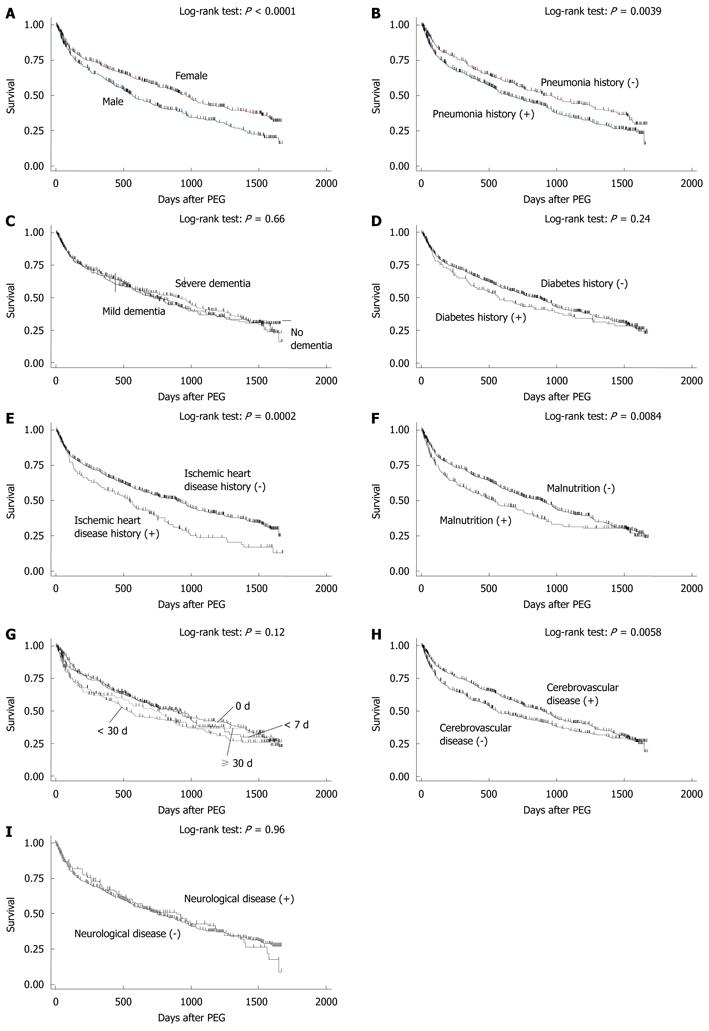

A Kaplan-Meier survival curve of the 931 patients was drawn (Figure 3): 99% survived more than 7 d; 95% survived more than 30 d; 88% survived more than 60 d; 75% survived more than 6 mo; 66% survived more than 1 year. Of the 931 patients, 50% and 25% survived 753 and 1647 d, respectively. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were then drawn for nominal or ordinal data (Figure 4). The prognosis of female patients was better than that of males (Figure 4A). Patients who had no history of pneumonia (Figure 4B) or ischemic heart disease (Figure 4E) survived longer than those with a history of the diseases. Patients who were considered as having malnutrition at the time of operation showed poorer survivals than those without malnutrition (Figure 4F). Patients whose comorbidity was cerebrovascular disease had a better outcome than patients with other comorbidities (Figure 4E). In contrast, the prognosis of patients with dementia (Figure 4C), diabetes (Figure 4D), or neurological disease (Figure 4I) were not different from those without the conditions. Duration of starvation before the PEG procedure had no significant impact on patient survival (Figure 4G).

Finally, using variables significant in the above analyses, Cox proportional hazard models were computed in single variable and multivariate analyses (Table 2). In single variable hazard models, patients with older age, and higher CRP, AST and BUN did show a significantly enhanced crude HR whereas higher Hb and albumin reduced the crude HR. In addition, no history of pneumonia or ischemic heart disease, no malnutrition, but a history of cerebrovascular disease significantly decreased crude HRs. However, in the multivariate hazard model, older age, higher CRP, higher BUN, lower albumin, male gender and a previous history of ischemic heart disease were significant risk factors of death after PEG insertion.

| Variable | Single variable analyses | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| Crude HR | 95% CI | P-value | AHR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age (yr) | 1.03 | 1.01-1.04 | < 0.001 | 1.02 | 1.00-1.03 | 0.009 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 1.07 | 1.05-1.10 | < 0.001 | 1.04 | 1.01-1.07 | 0.005 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.91 | 0.87-0.95 | < 0.001 | 0.98 | 0.92-1.05 | 0.530 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 1.01 | 1.00-1.01 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.10-1.00 | 0.170 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 1.01 | 1.01-1.02 | < 0.001 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.003 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.99 | 0.95-1.03 | 0.640 | 0.94 | 0.83-1.05 | 0.280 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.52 | 0.43-0.63 | < 0.001 | 0.67 | 0.52-0.85 | 0.001 |

| Female | 0.70 | 0.58-0.83 | < 0.001 | 0.60 | 0.48-0.75 | < 0.001 |

| No history of pneumonia | 0.76 | 0.63-0.92 | 0.004 | 0.99 | 0.79-1.24 | 0.950 |

| No history of ischemic heart disease | 0.66 | 0.53-0.82 | < 0.001 | 0.69 | 0.54-0.88 | 0.003 |

| No malnutrition | 0.76 | 0.63-0.93 | 0.009 | 1.09 | 0.85-1.39 | 0.490 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.78 | 0.66-0.93 | 0.006 | 0.83 | 0.67-1.02 | 0.080 |

In this study, 502 deaths were observed (mortality 53%). However, 99%, 95%, 88%, 75% and 66% of 931 patients survived more than 7, 30, 60 d, 6 mo and 1 year, respectively. In addition, 50% and 25% of the patients survived 753 and 1647 d, respectively, suggesting that more than half of geriatric patients treated with PEG may survive more than 2 years. Although the situations of each study may not be the same, the overall survival rate of this study is superior[8-10] or equivalent to previous reports[11-13]. Eight deaths out of 931 in the study population were reported as PEG-related, a rate almost equal to that in previous studies[14,15]. Although urinary tract infection and previous aspiration were predictive factors for death at 1 wk after PEG[16] and CRP was found to be predictive of early mortality[17], we also found that a lower albumin level was a significant risk factor for PEG-related death, which was a novel finding.

We also attempted to delineate prognostic factors for geriatric patients treated with PEG. In single variable analyses, older age, higher CRP, lower Ht/Hb, higher AST, higher BUN, lower albumin as well as male gender, previous history of pneumonia or ischemic heart disease, malnutrition, and non-cerebrovascular disease as an underlying disease at the PEG procedure, were significantly associated with death. In a multivariate hazard model, older age, higher CRP and higher BUN were significant poor prognostic factors of death after PEG formation, whereas higher albumin, female gender and no previous history of ischemic heart disease were markedly better prognostic factors. Thus, Hb, AST, previous history of pneumonia, malnutrition and cerebrovascular disease as an underlying disease were considered as confounders. Among prognostic factors significant in our study, older age, male sex, lower albumin levels and a previous history of pneumonia or aspiration were already recognized as poor prognostic factors[18-24]. In our single variable Cox hazard model, cerebrovascular disease as an underlying disease was a good prognostic factor, which was consistent with the previous evidence that patients with a previous diagnosis of stroke were more likely to be discharged home than others[25]. Thus, CRP, BUN and a previous history of ischemic heart disease were found as novel prognostic factors in our study.

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of the study strengths and limitations. The study was performed in multiple community and tertiary hospitals spread over Japan, which enhanced its generalizability. To minimize selection bias, collaborating doctors were asked to choose 20 consecutive patients. The sample size was close to 1000 and the results of the Cox hazard models were considered relatively robust. On the other hand, because of the retrospective nature of the study, we could collect only basic clinical information that might result in recall bias in areas such as previous histories and diagnosis of underlying diseases.

In conclusion, these results suggest that more than half of geriatric patients treated with PEG may survive longer than 2 years in Japan. In the Cox proportional multivariate analysis, older age, higher CRP and higher BUN were significant poor prognostic factors of death after PEG, whereas higher albumin, female gender and no previous history of ischemic heart disease were markedly better prognostic factors.

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) has been widely used for patients with swallowing difficulty, because of reduced laryngopharyngeal discomfort and a lower risk of aspiration pneumonia compared with the nasogastric tube. However, PEG feeding was found to be associated with an absolute increase in risk of death compared with nasogastric feeding. In spite of the evidence, PEG has been widely used especially for geriatric patients with the increasingly aging society.

Despite the very large number of patients receiving this intervention, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that PEG is beneficial for patients with swallowing difficulty due to dementia or other chronic diseases.

The patients were selected in a consecutive manner and followed up over a long time period.

In a Cox proportional multivariate analysis, older age, higher CRP and higher BUN were significant poor prognostic factors of death after PEG, whereas higher albumin, female gender and no previous history of ischemic heart disease were markedly better prognostic factors. The authors especially determined that a lower albumin level was a significant risk factor for PEG-related death, which was a novel finding.

Good comprehensive effort, gives nice insight into PEG in elderly.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Pankaj Garg, Consultant, Department of General Surgery, Fortis Super Speciality Hospital, Mohali, Punjab, Panchkula, 134112, India

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ Jr. Gastrostomy without laparotomy: a percutaneous endoscopic technique. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15:872-875. |

| 2. | Ponsky JL, Gauderer MW. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a nonoperative technique for feeding gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:9-11. |

| 3. | Ponsky JL, Gauderer MW, Stellato TA. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Review of 150 cases. Arch Surg. 1983;118:913-914. |

| 4. | Russell TR, Brotman M, Norris F. Percutaneous gastrostomy. A new simplified and cost-effective technique. Am J Surg. 1984;148:132-137. |

| 5. | Dennis MS, Lewis SC, Warlow C. Effect of timing and method of enteral tube feeding for dysphagic stroke patients (FOOD): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:764-772. |

| 6. | Sampson EL, Candy B, Jones L. Enteral tube feeding for older people with advanced dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD007209. |

| 7. | Langmore SE, Kasarskis EJ, Manca ML, Olney RK. Enteral tube feeding for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD004030. |

| 8. | Möller P, Lindberg CG, Zilling T. Gastrostomy by various techniques: evaluation of indications, outcome, and complications. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:1050-1054. |

| 9. | Leeds JS, McAlindon ME, Grant J, Robson HE, Lee FK, Sanders DS. Survival analysis after gastrostomy: a single-centre, observational study comparing radiological and endoscopic insertion. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:591-596. |

| 10. | Cowen ME, Simpson SL, Vettese TE. Survival estimates for patients with abnormal swallowing studies. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:88-94. |

| 11. | Nicholson FB, Korman MG, Richardson MA. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a review of indications, complications and outcome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:21-25. |

| 12. | Paramsothy S, Papadopoulos G, Mollison LC, Leong RW. Resumption of oral intake following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1098-1101. |

| 13. | Longcroft-Wheaton G, Marden P, Colleypriest B, Gavin D, Taylor G, Farrant M. Understanding why patients die after gastrostomy tube insertion: a retrospective analysis of mortality. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33:375-379. |

| 14. | Kohli H, Bloch R. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a community hospital experience. Am Surg. 1995;61:191-194. |

| 15. | Lockett MA, Templeton ML, Byrne TK, Norcross ED. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy complications in a tertiary-care center. Am Surg. 2002;68:117-120. |

| 16. | Light VL, Slezak FA, Porter JA, Gerson LW, McCord G. Predictive factors for early mortality after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:330-335. |

| 17. | Figueiredo FA, da Costa MC, Pelosi AD, Martins RN, Machado L, Francioni E. Predicting outcomes and complications of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2007;39:333-338. |

| 18. | Taylor CA, Larson DE, Ballard DJ, Bergstrom LR, Silverstein MD, Zinsmeister AR, DiMagno EP. Predictors of outcome after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a community-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67:1042-1049. |

| 19. | Jarnagin WR, Duh QY, Mulvihill SJ, Ridge JA, Schrock TR, Way LW. The efficacy and limitations of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Arch Surg. 1992;127:261-264. |

| 20. | Kirchgatterer A, Bunte C, Aschl G, Fritz E, Hubner D, Kranewitter W, Fleischer M, Hinterreiter M, Stadler B, Knoflach P. Long-term outcome following placement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in younger and older patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:271-276. |

| 21. | Tokunaga T, Kubo T, Ryan S, Tomizawa M, Yoshida S, Takagi K, Furui K, Gotoh T. Long-term outcome after placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2008;8:19-23. |

| 22. | Smith BM, Perring P, Engoren M, Sferra JJ. Hospital and long-term outcome after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:74-80. |

| 23. | Lang A, Bardan E, Chowers Y, Sakhnini E, Fidder HH, Bar-Meir S, Avidan B. Risk factors for mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2004;36:522-526. |

| 24. | Gaines DI, Durkalski V, Patel A, DeLegge MH. Dementia and cognitive impairment are not associated with earlier mortality after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33:62-66. |

| 25. | Fisman DN, Levy AR, Gifford DR, Tamblyn R. Survival after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy among older residents of Quebec. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:349-353. |