Published online Oct 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i40.5065

Revised: April 19, 2010

Accepted: April 26, 2010

Published online: October 28, 2010

AIM: To study the significance and clinical implication of hepatic lipogranuloma in chronic liver diseases, including fatty liver disease and hepatitis C.

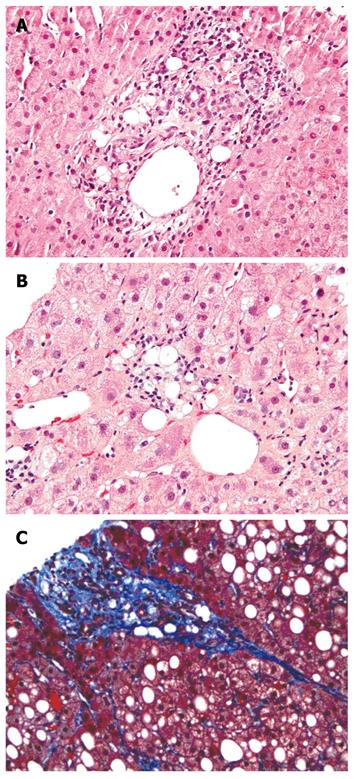

METHODS: A total of 376 sequential, archival liver biopsy specimens were reviewed. Lipogranuloma, steatosis and steato-fibrosis were evaluated with combined hematoxylin and eosin and Masson’s trichrome staining.

RESULTS: Fifty-eight (15.4%) patients had lipogranuloma, including 46 patients with hepatitis C, 14 patients with fatty liver disease, and 5 patients with other diseases. Hepatic lipogranuloma was more frequently seen in patients with hepatitis C (21%) and fatty liver disease (18%), and its incidence was significantly higher than that in control group (P < 0.0002 and P < 0.007, respectively). In addition, 39 out of the 58 patients with lipogranuloma were associated with steatosis and/or steato-fibrosis. Of the 18 lipogranuloma patients with clinical information available for review, 15 (83%) had risk factors associated with fatty liver disease, such as alcohol use, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. Although the incidence of these risk factors was greater in patients with lipogranuloma than in control group (60%), it did not reach statistical significance.

CONCLUSION: Hepatic lipogranuloma is not limited to mineral oil use and commonly associated with hepatic steatosis, hepatitis C and fatty liver disease. With additional histological features of steato-fibrosis, lipogranuloma can also be used as a marker of prior hepatic steatosis.

- Citation: Zhu H, Jr HCB, Clain DJ, Min AD, Theise ND. Hepatic lipogranulomas in patients with chronic liver disease: Association with hepatitis C and fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(40): 5065-5069

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i40/5065.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i40.5065

Chronic hepatitis C and fatty liver disease are the most common chronic liver diseases in the Western world[1-4]. Hepatitis C affects approximately 2.7 million individuals in the United States and up to 20% of them will eventually progress to cirrhosis[1,2]. It is well known that hepatitis C, particularly genotype 3, is associated with hepatic steatosis. On the other hand, it is estimated that up to two thirds of obese adults and nearly 50% of obese children can develop fatty liver disease[2]. A significant proportion of those patients can have concurrent hepatitis C and fatty liver disease. Hepatic steatosis can cause insulin resistance, decreased response to antiviral therapy, accelerated fibrosis, and cirrhosis[2,5].

Clinically, no effective laboratory test can evaluate hepatic steatosis, and liver biopsy remains the gold standard. However, one of the dilemmas in patients with suspected fatty liver disease is the occasional appearance of “non-fatty” liver biopsy specimens, particularly when cirrhosis is well established[6]. This deceptive histology can lead to erroneous diagnosis of so-called cryptogenic cirrhosis, most of which are now recognized as a “burnt-out” fatty liver disease[6,7]. Therefore, recognition of fatty liver disease, particularly in the absence of steatosis, is important for correct interpretation and management of patients with chronic liver disease.

Lipogranuloma, comprised of aggregates of lipid-containing histiocytes, is observed in liver biopsy specimens at an estimated frequency of 2.4%-5%[8,9]. Early investigations including lipid histochemistry analysis suggested that lipogranuloma is due to a reaction to absorbed saturated hydrocarbons, like mineral oil used widely in food, laxatives or oily vehicle for medication[10-13]. However, it has been shown that lipogranuloma is associated with hepatic steatosis[6,9,14,15]. The ruptured fat from lipid-containing hepatocytes can be taken up by macrophages and form lipogranuloma[9]. Lipid and its oxidative products can also stimulate inflammatory response, release cytokines, activate stellate cells and cause fibrosis[16-18].

Here, we reviewed 376 sequential liver biopsy patients to investigate the potential association of lipogranuloma with fatty liver disease and chronic hepatitis C.

All liver biopsy patients were retrieved from the archives in Department of Pathology, Beth Israel Medical Center of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Both routine hematoxylin and eosin (H/E) and Masson’s trichrome stained slides were reviewed. All hepatitis B and C patients were confirmed clinically by serology or molecular/PCR tests for viral genome. Viral hepatic necro-inflammation (activity) and fibrous scarring (stage) were evaluated according to the modified Ishak system[19].

Hepatic steatosis was evaluated based on the HE-stained slides, semi-quantitated as mild (< 1/3), moderate (1/3 to 2/3) and severe (> 2/3)[20], and further evaluated for the presence of steatohepatitis (hepatocyte ballooning, inflammatory cells, and Mallory’s hyaline) and steato-fibrosis (pericellular, perivenular, and/or portal fibrosis).

Hepatitis C-associated steatosis is most often mild and presents in a non-zonal distribution. When steatosis is more than that seen in patients with no complication of hepatitis C, and/or primary distribution in zone 3 with some features of pericellular and/or perivenular fibrosis, then a separate diagnosis of concurrent fatty liver disease is rendered, recognizing that hepatitis C itself may be a potential cause of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome[21-23].

In the absence of significant steatosis (> 5%), identification of pericellular or perivenular fibrosis on the trichrome-stained slides suggests a tentative diagnosis of resolving fatty liver disease.

Lipogranuloma, comprised of loose aggregates of lipid-containing macrophages, lymphocytes, and a few poorly developed epithelioid cells, was evaluated on both H&E and trichrome-stained slides. Morphologically, lipogranuloma is different from the foam cell aggregates resulting from scavenge of dying hepatocytes. The later usually contains PASD-positive foamy cytoplasm without lipid vacuoles. They were also further classified according to their location: portal/periportal, perivenular, parenchymal, or their combination. Of the 58 patients with lipogranuloma, 18 had clinical chart information available for review for the presence of known risk factors associated with fatty liver disease such as history of alcohol use, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and obesity. The control group was consisted of forty sequentially retrieved cases out of the total 376 patients that were absent of lipogranuloma on liver biopsy, but had clinical chart information available for review of risk factors for fatty liver disease.

Fisher exact test was used for statistical analyses. A two-tailed P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Liver biopsy specimens from 376 patients were studied. The average age of patients was 48.8 years (range 19-85 years) and the male to female ratio was 1.5:1. Diagnosis was established as chronic hepatitis C in 217 (58%) patients, fatty liver disease in 80 (21%) patients, chronic hepatitis B in 56 (15%) patients, autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) in 13 (3.5%) patients, primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) in 11 (3%) patients, and other diseases in 47 (13%) patients including nonspecific changes in 14, malignancy in 10, no pathological alteration in 6, resolving hepatitis in 5, methotrexate-related changes in 3, hemosiderosis in 3, cholestasis in 2, necrotizing granuloma in 1, sarcoid granuloma in 1, hepatic adenoma in 1, and bile duct paucity with unknown cause in 1 (Table 1). Of the 217 patients with chronic hepatitis C, 38 (17.5%) had histologically and clinically concurrent fatty liver disease. Of the 40 patients in control group, 60%, 12.5%, 12.5%, and 10% were diagnosed as hepatitis C, FLD, hepatitis B, and other diseases, respectively.

| Disease | Patients1 | Lipogranuloma patients | P |

| HCV (all) | 217 (58) | 46 (21) | 0.0002 |

| HCV alone | 160 (43) | 36 (22.5) | 0.0001 |

| HCV + FLD | 38 (10) | 7 (18) | 0.0200 |

| HCV + other | 19 (5) | 3 (16) | 0.1000 |

| FLD (all) | 80 (21) | 14 (18) | 0.0070 |

| FLD alone | 24 (6.4) | 5 (21) | 0.0240 |

| FLD + HCV | 38 (10) | 7 (18) | 0.0200 |

| FLD + other | 18 (5) | 2 (11) | 0.2600 |

| Non-HCV/FLD | 116 (31) | 5 (4) | |

| HBV | 56 (15) | 2 (3.6) | |

| PBC | 11 (3) | 1 (9) | |

| AIH | 13 (3.5) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Other | 47 (13) | 3 (6) |

Lipogranuloma was identified in 58(15.4%) out of the 376 liver biopsy specimens with HE and Masson’s trichrome staining. The average age of these patients was 52.6 years (range 22-70 years) and the male to female ratio was 2.6:1. Of the 58 patients with lipogranuloma, 46 were diagnosed as chronic hepatitis C (21% of total hepatitis C patients), 14 as fatty liver disease (18% of total fatty liver disease patients, including 7 with concurrent hepatitis C), 2 as hepatitis B (1 with concurrent fatty liver disease), 1 as PBC, 1 as AIH with concurrent fatty liver disease, and 3 as other diseases (1 with lipofuscinosis, 1 with non-specific change, and 1 with no pathological alteration). The incidence of lipogranuloma was significantly higher in patients with hepatitis C and fatty liver disease than in controls (P < 0.0002 and P < 0.007, respectively). However, the difference was statistically less significant in patients with fatty liver disease when those with concurrent hepatitis C were excluded (P = 0.024) (Table 1).

Approximate one third of the patients had only single lipogranuloma, while the remaining patients had multiple lesions. The distribution of lipogranulomas varied from portal (zone 1) to central area (zone 3), including portal/periportal in 24 patients, perivenular in 16 patients, both portal and perivenular in 16 patients, and both portal and parenchymal distribution in 2 patients. In the 14 lipogranuloma patients with the diagnosis of fatty liver disease, the distribution of lipogranuloma was similar (portal in 5, perivenular in 3, and combination in 6) (Figure 1), indicating that lipogranuloma distribution does not correlate with any disease category.

The typical patterns of mild to moderate fibrosis associated with fatty liver disease were sclerosis of central veins and/or delicate thin fibrous bands distributed in perivenular and acinus zone 3. Of the 58 lipogranuloma patients, 12 had perivenular/pericellular fibrosis only, 14 had steatosis only, 14 had both steatosis and fibrosis, and 18 had neither steatosis nor fibrosis. Overall, 39 (67%) out of the 58 lipogranuloma patients were associated with either steatosis or steato-fibrosis. However, most lipogranuloma-containing biopsy specimens showed either steatosis (13%, 32 out of 237 patients) or mild steatosis (26%, 19 out of the 73 patients) and moderate to severe steatosis (12%, 8 out of the 66 patients).

In order to further investigate the relationship between lipogranuloma and fatty liver disease, we reviewed the patients’ clinical information for history of risk factors for fatty liver disease, including alcohol drinking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, or hyperlipidemia. Of the 18 patients with chart information available for review, 15 (83%) had at least one of the risk factors associated with fatty liver disease (Table 2). However, 24 (60%) of the 40 patients in control group also had clinical risk factors for fatty liver disease, which did not reach the statistical significance.

| Patient | Diagnosis | Alcohol hx | Diabetesmellitus | Hyper-lipidemia | Obesity |

| 1 | Cirrhosis, 4/4 | Y | N | N | N |

| 2 | HCV, 3/4 | N | N | Y | N |

| 3 | HBV, 1/4 | N | N | Y | N |

| 4 | HCV, 2/4 | Y | N | N | N |

| 5 | HCV, 2/4 | Y | N | Y | Y |

| 6 | HCV, 1/4 | ? | N | ? | Y |

| 7 | HCV, 2/4 | Y | N | N | N |

| 8 | HCV, 2/4 | Y | N | N | N |

| 9 | HCV, 1/4, iron 2/4 | Y | ? | ? | N |

| 10 | HCV, FLD, 1/4 | Y | N | N | N |

| 11 | HCV, 1/4 | Y | N | N | Y |

| 12 | Resolving FLD | N | N | N | Y |

| 13 | AIH | N | N | N | Y |

| 14 | FLD | N | N | Y | Y |

| 15 | HCV, 1/4 | N | N | Y | Y |

| Total | 15 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 7 |

Earlier studies suggested that lipogranuloma is an incidental finding with no particular clinical significance[10,13]. Histochemical analysis of lipid extracts from non-fatty liver and food showed that lipogranuloma in non-fatty liver is likely caused by a reaction to the ingested, absorbed, and saturated hydrocarbons similar to mineral oil[10]. It has been reported that lipogranuloma can be found in 48% of livers without obvious association with steatosis, suggesting that lipogranuloma is probably related to mineral oil with no clinical significance[10,13].

However, ultrastructural examination of severe fatty liver biopsy specimens suggested that lipogranuloma is also probably formed from fat droplets[12]. A more recent study also indicated that lipogranuloma may be associated with fatty liver disease, particularly in alcoholic patients[15]. When lipid release overwhelms the ability of lipid absorption, the excess fat can be taken up by macrophages and form lipogranuloma[9]. Recent studies suggested that lipid release from ruptured hepatocytes can cause lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammatory injury to hepatocytes and venules, releasing inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor, thus further activating stellate cells and ultimately causing fibrosis[16-18].

Over the last two decades, hepatitis C and fatty liver disease have become the most common chronic liver diseases in the United States and our sample shows a similar demographic profile which consists of 58% of hepatitis C patients and 21% of fatty liver disease patients. The frequency of lipogranuloma (15.4%) in our study was significantly higher than that of previously reported (2.4%-5%). In our study, lipogranuloma was most often identified in biopsy specimens from patients with hepatitis C (21%) and/or fatty liver disease (18%), while the prevalence remained similar to historical levels in hepatitis B and other diseases, suggesting that an increased incidence of lipogranulomas is related to fat accumulation seen in patients with hepatitis C and fatty liver disease. Lipogranuloma in patients with pure fatty liver disease, exclusive of concurrent hepatitis C, was statistically less significant (P = 0.024), suggesting that lipogranuloma is more closely related to chronic hepatitis C than to fatty liver disease.

It is well known that hepatitis C, particularly genotype 3, is associated with steatosis. Hepatic steatosis is found in 50%-80% of individuals with hepatitis C[2,5]. Meanwhile, 5%-18% of hepatitis C patients have concurrent fatty liver disease on biopsy[5]. Hepatitis C-associated steatosis, usually mild and located in a random distribution, is also recognized. However, hepatitis C-associated steatosis may directly cause insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome with patterns of steatosis typical for overt fatty liver disease[19,21,23]. The fact that there are more lipogranulomas seen in patients with hepatitis C than in those with fatty liver disease suggests that there may be factors other than steatosis that are associated with lipogranuloma formation. One may consider that the unique combination in hepatitis C with increased hepatocyte turnover from chronic viral infection and concomitant hepatocyte steatosis, may lead to increased lipid release from injured or dead steatotic hepatocytes, thus promoting lipogranuloma formation. Other unknown factors that may also play a significant role in lipogranuloma formation remain to be elucidated.

The previously reported mineral oil-related lipogranuloma is mainly formed around the portal tract, presumably due to lipid taken up by macrophages immediately upon entry into the liver via the portal vein after absorption from the gastrointestinal tract[10,13]. In our study, lipogranuloma was more evenly distributed from portal to central area, and 40 out of the 58 lipogranuloma patients were accompanied with steatosis, steato-fibrosis, or both, suggesting that lipogranuloma seen in the current study is more likely associated with steatosis from hepatitis C or fatty liver disease rather than with mineral oil ingestion or laxative use. More importantly, most of these lipogranulomas are also associated with other histological features of fatty liver disease. Review of the patients’ chart information, when possible, also indicated that 15 (83%) of the 18 patients with lipogranuloma had at least one of the risk factors for fatty liver disease, including alcohol drinking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, or hyperlipidemia, which was higher than that in controls (60%), although no statistical insignificance was reached.

Our data, therefore, suggest that lipogranuloma is potentially associated with hepatic steatosis. We hypothesize that lipogranuloma is resulted from hepatocellular lipid accumulation (either from direct hepatitis C viral infection or through insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome arising from that virus, or from alcohol use, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and/or dyslipidemia syndrome), necroinflammatory activity due to virus or steatohepatitis, release of lipid from injured hepatocytes, uptake of released lipid by macrophages, and finally formation of lipogranulomas. The presence of such lesions in the absence of current steatosis (some of which also show persistent steato-fibrosis) suggests that lipogranulomas, particularly those away from the portal tract, may be indicative of prior hepatic steatosis and most probably of resolved or resolving fatty liver disease (in the absence of hepatitis C).

It is well recognized that many of those liver diseases previously labeled as cryptogenic cirrhosis are actually a burnt-out fatty liver disease[1]. Therefore, persistence of lipogranuloma in otherwise non-fatty liver disease, particularly in the absence of steatosis, is important for unmasking the nature of past, more active liver disease and facilitating correct interpretation and management of patients.

In conclusion, while mineral oil may play a role in some lipogranulomas as reported, most of the lipogranulomas in current liver disease patients are related to hepatic steatosis. Lipogranuloma can be used as a surrogate for prior, more active hepatic steatosis possibly related to hepatitis C. The otherwise normal liver biopsy specimen containing lipogranuloma (with or without mild, subtle steato-fibrosis) perhaps should not be considered “normal”, but rather as an indicator of past, now resolving fatty liver disease, a diagnostic finding that is not without possible clinical relevance. Whether the presence of lipogranuloma also has prognostic importance in patients with chronic hepatitis C remains to be explored in follow-up analysis.

Fatty liver disease and hepatitis C have been the most common chronic liver diseases in the United States and both are associated with steatosis in the liver. Hepatic lipogranuloma has been previously regarded as mineral oil-related, incidental findings and its role in hepatic steatosis is rarely discussed. It will be interesting and potentially clinically significant to elucidate lipogranuloma, which may also be more significantly related to hepatic steatosis rather than to mineral oil laxative use.

Fatty liver disease has become endemic in the United States. Clinically, patients with suspend fatty liver disease may have "non-fatty" appearance on liver biopsy and the disease of these patients may progress without proper treatment. Some of these patients may eventually develop so called "cryptogenic cirrhosis". Therefore, it will be very interesting and clinically important to study the relationship between hepatic lipogranuloma, fatty liver disease and hepatitis C.

This study reviewed the sequential liver biopsies and the association of lipogranuloma with chronic liver diseases, demonstrating that lipogranuloma is more commonly seen in patients with hepatitis C and fatty liver disease. Lipogranuloma associated with other features, such as steato-fibrosis, can be used as a potential marker of prior fatty liver disease.

By showing the potential association of lipogranulomas with hepatitis C and fatty liver disease, the authors can identify under recognized fatty liver disease.

Lipogranuloma is due to histiocytic reaction to lipid aggregate. Steato-fibrosis is typically seen in around the hepatocytes and central venules more commonly seen in fatty liver disease.

This manuscript presents some interesting data based on an observation in a large series of liver biopsies. The authors tried to link the morphologic phenotype to hepatic steatosis and hepatitis C, which may contribute to a better understanding of lipogranuloma formation.

Peer reviewers: Takashi Kojima, DVM, PhD, Department of Pathology, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, S.1, W.17, Chuo-ku, Sapporo 060-8556, Japan; María IT López, Professor, Experimental Biology, University of Jaen, araje de las Lagunillas s/n, Jaén 23071, Spain; Qin Su, Professor, Department of Pathology, Cancer Hospital and Cancer Institute, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Medical College, PO Box 2258, Beijing 100021, China

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Bell BP, Manos MM, Zaman A, Terrault N, Thomas A, Navarro VJ, Dhotre KB, Murphy RC, Van Ness GR, Stabach N. The epidemiology of newly diagnosed chronic liver disease in gastroenterology practices in the United States: results from population-based surveillance. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2727-2736; quiz 2737. |

| 2. | Cheung O, Sanyal AJ. Hepatitis C infection and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2008;12:573-585, viii-ix. |

| 3. | Ong JP, Younossi ZM. Epidemiology and natural history of NAFLD and NASH. Clin Liver Dis. 2007;11:1-16, vii. |

| 4. | Stamatakis E, Primatesta P, Chinn S, Rona R, Falascheti E. Overweight and obesity trends from 1974 to 2003 in English children: what is the role of socioeconomic factors? Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:999-1004. |

| 5. | Blonsky JJ, Harrison SA. Review article: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C virus--partners in crime. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:855-865. |

| 6. | Hübscher SG. Histological assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Histopathology. 2006;49:450-465. |

| 7. | Ayata G, Gordon FD, Lewis WD, Pomfret E, Pomposelli JJ, Jenkins RL, Khettry U. Cryptogenic cirrhosis: clinicopathologic findings at and after liver transplantation. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:1098-1104. |

| 8. | Delladetsima JK, Horn T, Poulsen H. Portal tract lipogranulomas in liver biopsies. Liver. 1987;7:9-17. |

| 9. | Scheuer PJ, Lefkowitch JH. Liver biopsy interpretation. 7th ed. Elsevier Sanders, 2006. . |

| 10. | Dincsoy HP, Weesner RE, MacGee J. Lipogranulomas in non-fatty human livers. A mineral oil induced environmental disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1982;78:35-41. |

| 11. | Landas SK, Mitros FA, Furst DE, LaBrecque DR. Lipogranulomas and gold in the liver in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:171-174. |

| 12. | Petersen P, Christoffersen P. Ultrastructure of lipogranulomas in human fatty liver. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1979;87:45-49. |

| 13. | Wanless IR, Geddie WR. Mineral oil lipogranulomata in liver and spleen. A study of 465 autopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1985;109:283-286. |

| 14. | Christoffersen P, Braendstrup O, Juhl E, Poulsen H. Lipogranulomas in human liver biopsies with fatty change. A morphological, biochemical and clinical investigation. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1971;79:150-158. |

| 15. | Morita Y, Ueno T, Sasaki N, Kuhara K, Yoshioka S, Tateishi Y, Nagata E, Kage M, Sata M. Comparison of liver histology between patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and patients with alcoholic steatohepatitis in Japan. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:277S-281S. |

| 16. | Day CP, James OF. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842-845. |

| 17. | Lieber CS. Alcoholic fatty liver: its pathogenesis and mechanism of progression to inflammation and fibrosis. Alcohol. 2004;34:9-19. |

| 18. | Wanless IR, Shiota K. The pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and other fatty liver diseases: a four-step model including the role of lipid release and hepatic venular obstruction in the progression to cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:99-106. |

| 19. | Theise ND. Liver biopsy assessment in chronic viral hepatitis: a personal, practical approach. Mod Pathol. 2007;20 Suppl 1:S3-S14. |

| 20. | Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2467-2474. |

| 21. | Fartoux L, Poujol-Robert A, Guéchot J, Wendum D, Poupon R, Serfaty L. Insulin resistance is a cause of steatosis and fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2005;54:1003-1008. |

| 22. | Goodman ZD, Ishak KG. Histopathology of hepatitis C virus infection. Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15:70-81. |

| 23. | Tsochatzis EA, Manolakopoulos S, Papatheodoridis GV, Archimandritis AJ. Insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in chronic liver diseases: old entities with new implications. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:6-14. |