Published online Oct 21, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i39.4998

Revised: April 15, 2010

Accepted: April 22, 2010

Published online: October 21, 2010

AIM: To study the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) presenting as bile duct tumor thrombus with no detectable intrahepatic mass.

METHODS: Six patients with pathologically proven bile duct HCC thrombi but no intrahepatic mass demonstrated on the preoperative imaging or palpated intrahepatic mass during operative exploration, were collected. Their clinical and imaging data were retrospectively analyzed. The major findings or signs on comprehensive imaging were correlated with the surgical and pathologic findings.

RESULTS: Jaundice was the major clinical symptom of the patients. The elevated serum total bilirubin, direct bilirubin and alanine aminotransferase levels were in concordance with obstructive jaundice and the underlying liver disease. Of the 6 patients showing evidence of viral hepatitis, 5 were positive for serum alpha fetoprotein and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and 1 was positive for serum carcinoembryonic antigen. No patient was correctly diagnosed by ultrasound. The main features of patients on comprehensive imaging were filling defects with cup-shaped ends of the bile duct, with large filling defects presenting as casting moulds in the expanded bile duct, hypervascular intraluminal nodules, debris or blood clots in the bile duct. No obvious circular thickening of the bile duct walls was observed.

CONCLUSION: Even with no detectable intrahepatic tumor, bile duct HCC thrombus should be considered in patients predisposed to HCC, and some imaging signs are indicative of its diagnosis.

- Citation: Long XY, Li YX, Wu W, Li L, Cao J. Diagnosis of bile duct hepatocellular carcinoma thrombus without obvious intrahepatic mass. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(39): 4998-5004

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i39/4998.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i39.4998

Obstructive jaundice associated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is not common, with an incidence of 0.5%-13% in patients with HCC[1-11]. This type of HCC is also known as icteric type of HCC (IHCC)[5-7]. Bile duct tumor thrombus (BDTT) is the leading cause of obstruction in IHCC. It has been shown that HCC is smaller in patients with biliary tumor thrombi than in those without biliary tumor thrombi, with a mean tumor size of 3.8 ± 2.1 cm vs 6.7 ± 4.6 cm[8]. Several studies[9-11] concerning IHCC reported that primary hepatic parenchymal tumor is detectable in most patients with IHCC while no obvious intrahepatic tumor is detectable in only 2.9%-25.0% of patients with biliary HCC thrombi. We encountered 6 patients with this special type of IHCC. Postoperative pathologic examinations “surprisingly” proved that the bile duct nodules leading to obstructive jaundice were HCCs. However, neither intrahepatic mass nor portal vein thrombus was identified on the preoperative imaging or even during explorative surgery. This type of IHCC is very rare and difficult to diagnose, and only few cases have been occasionally reported[12-17], without their features summarized. We retrospectively analyzed the clinical and imaging data about 6 patients with emphasis laid on the diagnostic imaging correlated with pathologic and surgical data, and clinical features and imaging signs that might lead to the diagnosis.

This study was approved by our institutional review board. Informed consent was not obtained from the patients as this was a limited, anonymous retrospective review of patient data.

Six patients including 5 men and 1 woman at the age of 47-64 years were confirmed with bile duct HCC by surgery and histology between January 2000 and November 2008 at our hospital. Their medical records were thoroughly reviewed and cross-checked.

Jaundice was the predominant symptom of the patients, and presented as an initial symptom of 4 patients. The time from the onset of jaundice to admission was 7 d-3 mo (median 1 mo). The other main clinical symptoms were fatigue, right upper quadrant abdominal pain or upper abdominal pain, abdominal distension, loss of appetite and loss of weight. Liver function reserve was Child grade A and B in 4 and 2 patients, respectively.

Laboratory data about the patients before surgery were recorded and analyzed.

Each patient underwent two or more preoperative diagnostic imaging procedures, including transabdominal ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT) with plain scan and arterial and portal phase contrast enhanced scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC). All available imaging data including diagnosis reports and images were retrospectively reviewed by two radiologists with more than 5 years of experience in abdominal imaging. A consensus was reached with the main findings or signs recorded.

Surgical records and pathologic reports were also reviewed and correlated with the major findings or signs on comprehensive imaging.

The levels of total serum bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), α-fetoprotein (AFP), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) of each patient are listed in Table 1.

| Patient No./sex/age (yr) | TBIL (μmol/L) | DBIL (μmol/L) | ALT (U/L) | HBsAg | AFP (ng/mL) | CA19-9 (U/mL) | CEA (μg/L) |

| 1/M/48 | 364.4 | 145.7 | 99.4 | Positive | 159 | 123.1 | 2.82 |

| 2/F/64 | 265.1 | 110.2 | 190.9 | Positive | 12.4 | > 575 | 3.24 |

| 3/M/47 | 268.6 | 146.4 | 127.4 | Positive | 263 | 465.7 | 7.10 |

| 4/M/51 | 277.3 | 156.1 | 137.2 | Positive1 | > 1210 | Unknown | Unknown |

| 5/M/53 | 373.9 | 153.6 | 133.8 | Positive | Negative | 183.1 | 1.52 |

| 6/M/55 | 344.2 | 199.3 | 204.0 | Positive | 10.7 | 164.9 | 3.90 |

Transabdominal US was performed, showing dilatated intrahepatic ducts with nodules in hilar bile ducts but no intrahepatic mass. The intraluminal nodules were hypoechoic, slightly hyperechoic, and mixed echoic in 4, 1, and 1 patients, respectively. Three and 1 patients were diagnosed as hilar cholangiocarcinoma and choledocholithiasis, respectively. Further evaluation was needed in 2 patients.

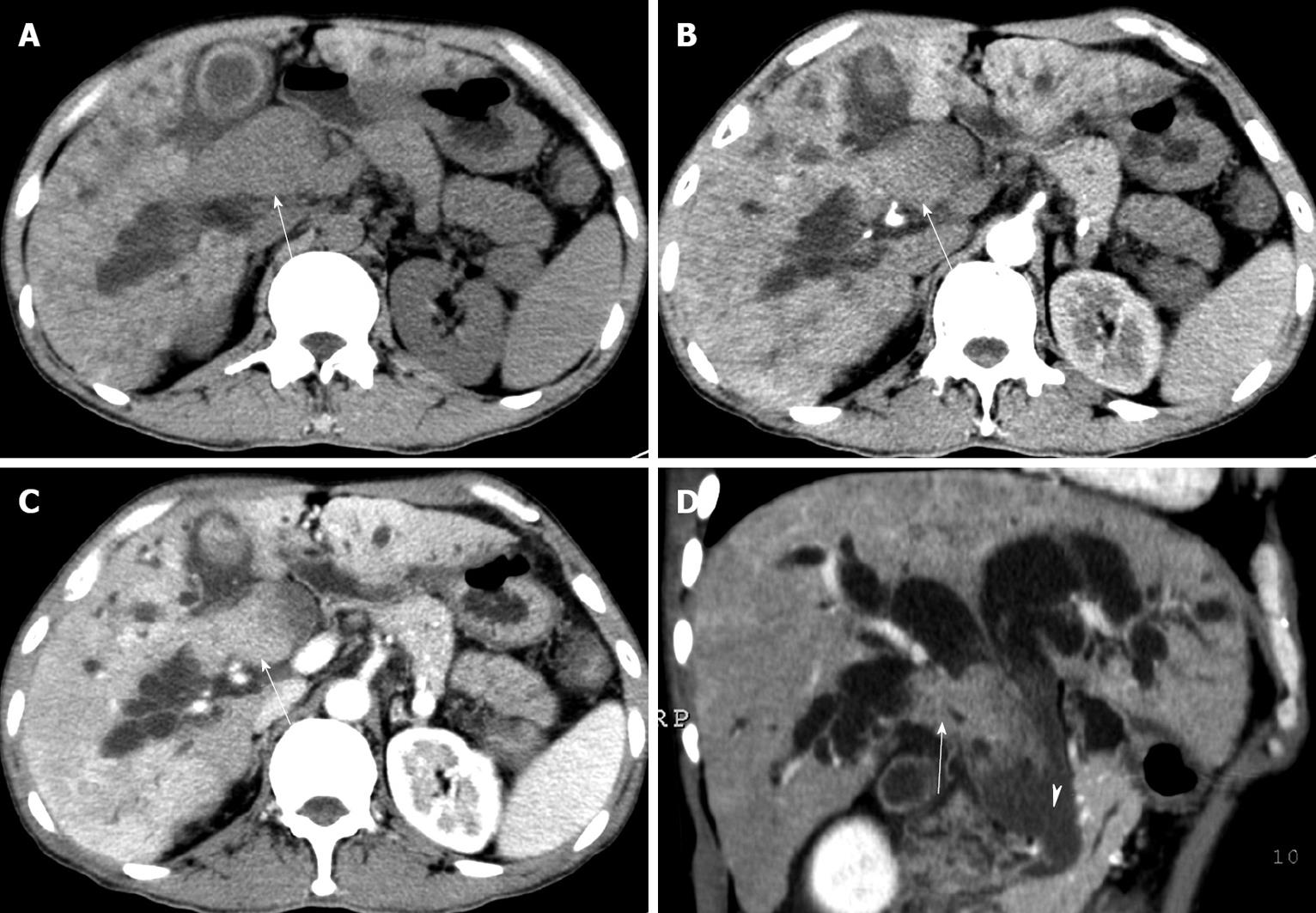

CT with pre-contrast scan and dual-phase contrast-enhanced scan was performed for 5 patients, showing dilated bilateral intrahepatic ducts with an intraductal nodule obstructing the hilar bile duct and/or common bile duct, but no tumor thrombus in the portal vein or systemic vein and no obvious mass in the hepatic parenchyma. These intraductal nodules were relatively mild hypodense to the hepatic parenchyma on pre-contrast images. During the arterial phase, they showed different degrees of enhancement and were relatively isodense or mildly hyperdense to the hepatic parenchyma. The enhancement of intraductal nodules was relatively lower in portal phase than that of hepatic parenchyma. In three lesions with the longest diameter greater than 3.0 cm, the intraluminal nodules appeared as cast moulds in the dilated ducts without obvious thickening of the walls. Non-enhanced sludge, which was mildly hyperdense in the bile, was observed in the common bile duct of 2 patients (Figure 1). The sludge was found to be tumor debris or hemorrhage of tumor at surgery. CT showed signs of liver cirrhosis in 4 patients, such as splenomegaly, varices, heterogeneously attenuated liver with lacelike fibrosis and regenerative nodules, and irregular or nodular liver surface. A small amount of ascites was present in 1 patient.

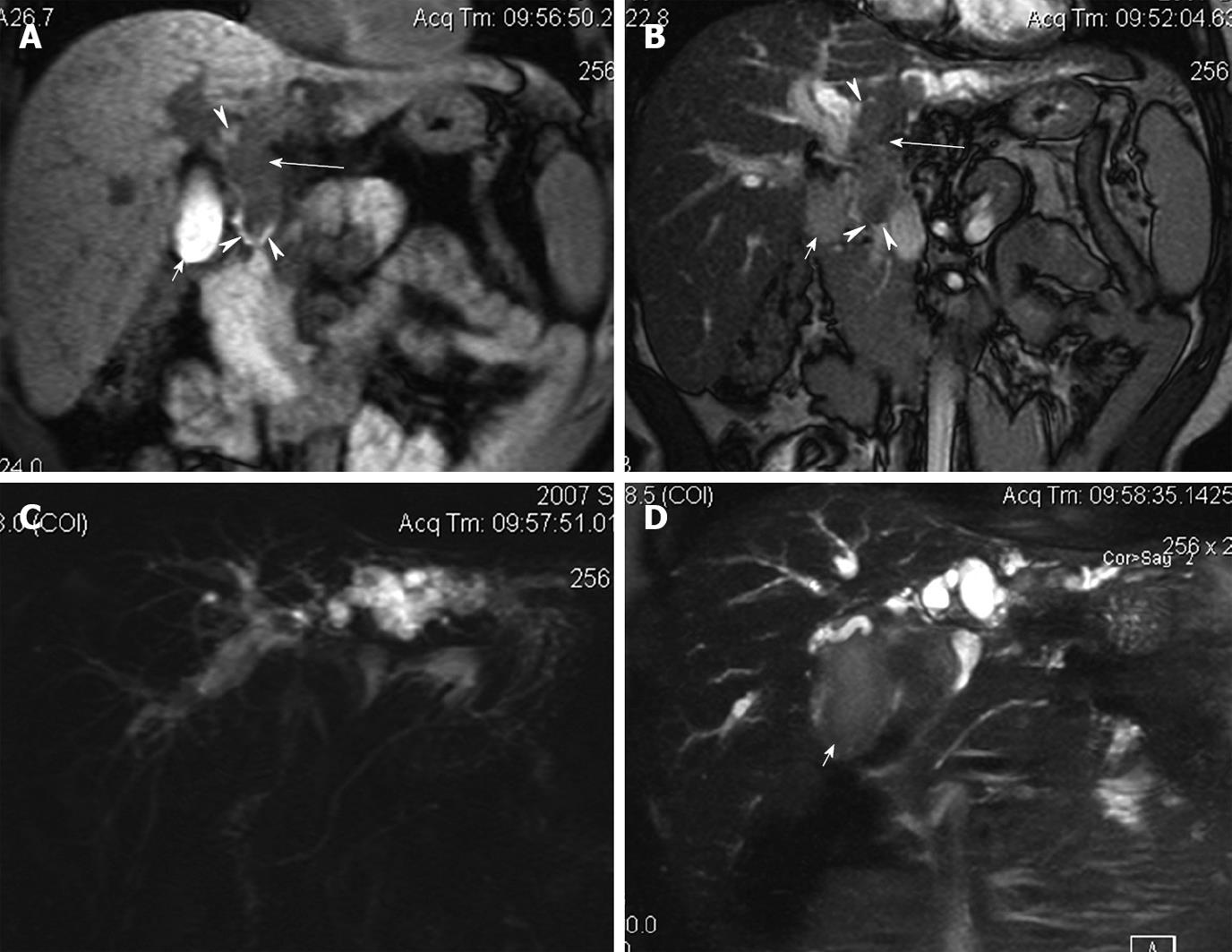

Conventional non-enhanced MRI combined with MRCP was performed for 3 patients, showing no mass in the hepatic parenchyma or portal vein. MRCP images showed moderate-severe dilatation of bilateral hepatic ducts with columnar or plugged filling defect of bile ducts in the hilar area. The filling defects were hypointense on T1-weighted images and iso or mild hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The intraluminal nodule was originated from the left hepatic duct and extended downward into the common bile duct of 1 patient accompanying a short T1 signal in surrounding bile duct and gallbladder due to intraluminal hemorrhage of tumor confirmed at surgery (Figure 2). Debris as a sludge-like filling defect was observed in the common bile duct of another patient.

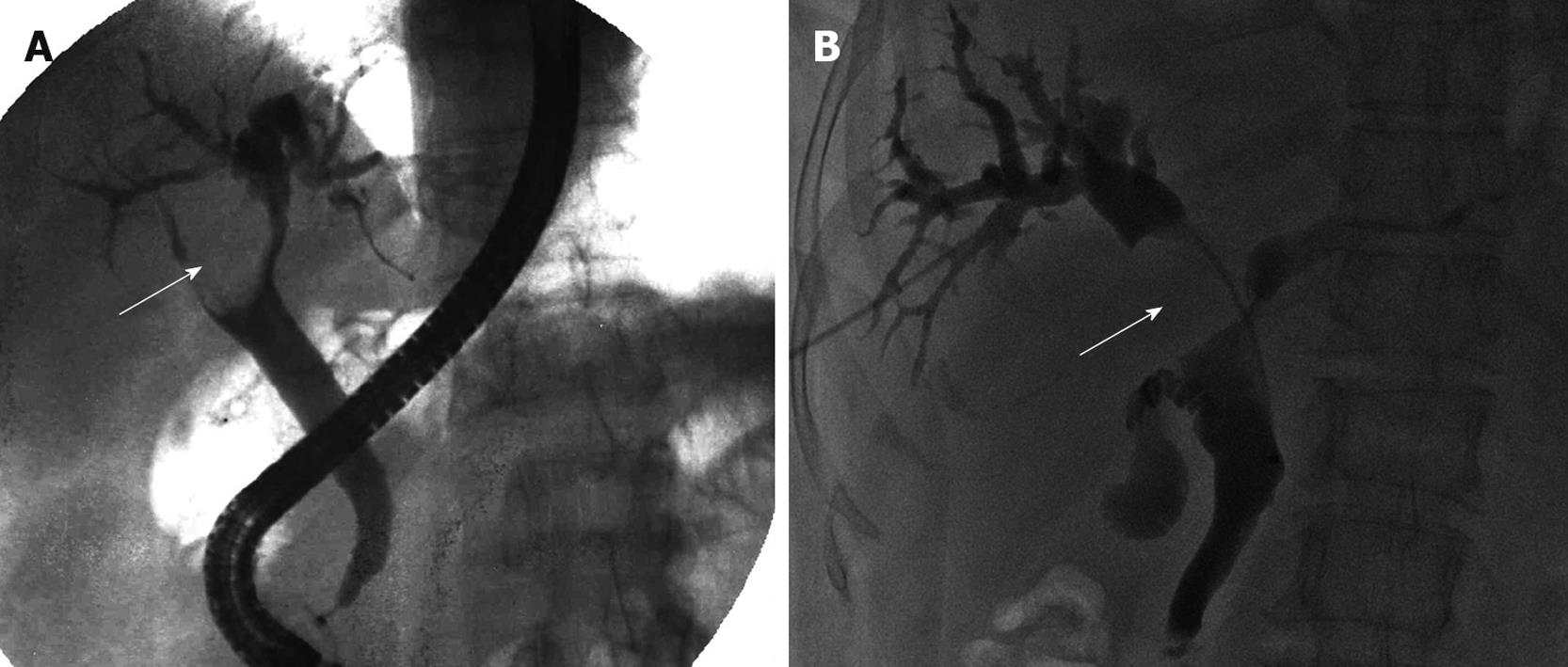

ERCP was performed for 1 patient, showing a smooth oval filling defect in the upper common bile, common and right hepatic ducts with dilated intrahepatic ducts (Figure 3A). The cup-shaped filling defect caused dilatation of the bile duct. Gallbladder was not visualized because of obstruction by the tumor.

PTC was performed for 1 patient, showing an oval smooth intraluminal filling defect in common and right hepatic ducts with dilated intrahepatic ducts (Figure 3B). Both ends of the filling defect were cup-shaped.

Tumor thrombi in bile ducts and evident hepatic cholestasis were found in 6 patients during surgery. Typical liver cirrhosis was found in 4 patients. Diffuse HCC was not considered because none of them had evidence of tumor invasion of the portal vein or system vein. No obvious intrahepatic mass was palpated in all patients. Diffuse miliary peritoneum metastasis was observed in 1 patient and thought to be infiltration of the tumor in hilar duct. The tumor thrombi were dark brown, dark red or yellowish brown in color, and soft or slightly elastic, relatively friable, and extremely vascular tending to bleed even on light touch. Most of them were easily separated from the bile duct walls. Sludge-like debris or small blood clots were found in the common bile ducts of 4 patients and blood-stained bile was found in the intrahepatic ducts of 2 patients. Removal of tumor thrombi was attempted in 6 patients and was successful without active hemorrhage in 4 patients. Partial hepatectomy was performed for 2 patients, and aborted in 4 patients due to the poor liver function reserve or peritoneal metastasis. Further exploration after clearance of thrombi revealed relatively smooth internal walls of common bile duct (CBD) and common hepatic duct (CHD). The resected liver tissue revealed a small hepatic parenchymal tumor in each, 0.5 cm × 1.0 cm and 0.8 cm × 1.5 cm in size.

The pathologic reports of intrabiliary thrombi revealed HCC but no variants of cholangiocarcinoma, mixed type of HCC or cholangiocarcinoma in 6 patients. Of the 6 patients, 2 had poorly-differentiated HCC, 3 had poorly-moderately differentiated HCC, and 1 had moderately-differentiated HCC, which accompanied hemorrhage or necrotic tissue in most of the 6 patients.

Portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT) is frequently seen in HCC patients. However, HCC presented as biliary duct tumor thrombus (BDTT) is a relatively rare entity. Intrahepatic tumor or PVTT is evident in most of patients with HCC presented as BDTT, yet few patients with HCC thrombi in the bile duct but without any detectable intrahepatic mass or PVTT have been reported[9-17]. In this circumstance, it is difficult but still important to establish the correct diagnosis, especially to differentiate it from cholangiocarcinoma or diffuse-type HCC. Because the therapeutic plan for HCC presented as BDTT may be substantially different from that for cholangiocarcinoma and diffuse-type HCC, surgery can often be offered when the disease is still localized[1,2,10-20], while percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage (PTCD) combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) serves as an effective alternative therapy especially when the tumor is unresectable[1,6,7]. We retrospectively analyzed the clinical and imaging data about these patients, and found that some features might be helpful for the diagnosis.

Jaundice is the predominant clinical presentation of this disease[1-21]. Causes of obstructive jaundice in this type of HCC include intraluminal growth of tumor leading to obstruction of intra or extrahepatic ducts, tumor tissue fragments and/or hemorrhages or blood clots due to necrosis, bleeding, and detachment of intraductal tumors, giving rise to the obstruction, which are similar to the reported findings in IHCC[3].

Apart from jaundice, there are also other non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, abdominal pain, abdominal distension and loss of appetite. A differential diagnosis between this and other common diseases causing obstructive jaundice such as cholangiocarcinoma and choledocholithiasis is essential.

In this study, all the 6 patients were positive for the markers of chronic viral hepatitis. The proportion of liver cirrhosis was relatively high with typical liver cirrhosis found in 4 patients. The elevated serum ALT level in our patients might be associated with the underlying disease. The majority of patients were middle-aged or old males. These features were also found in common types of HCC.

Serum tumor markers may be helpful in the diagnosis of this disease[22]. Positive serum AFP supports the diagnosis of HCC, while CEA level is frequently elevated in patients with cholangiocarcinoma. In this study, the positive ratios for AFP and CA19-9 were high, suggesting that positive AFP and CA19-9 support the diagnosis. However, positive CA19-9 may also frequently be seen in cholangitis, bile duct stones and biliary or pancreatic tumors leading to obstructive jaundice[23]. Thus, its value for differential diagnosis has to be further evaluated in studies with more cases.

Several diagnostic imaging methods play an important role in the diagnosis of obstructive jaundice[24-31]. The location and extent of obstruction can be reliably demonstrated using proper techniques, and the cause of obstruction can often be inferred by analyzing the morphology of obstruction site and other relevant signs. Transabdominal US is the most widely used and usually the initial tool to evaluate obstructive jaundice. However, none of our patients was correctly diagnosed by transabdominal US, and most of them were misdiagnosed as cholangiocarcinoma. Tamada et al[29] reported that intraductal US (IDUS) can distinguish between tumor thrombi caused by HCC and polypoid type cholangiocarcinoma. However, IDUS has not been widely accepted because it is invasive and requires special equipments and specific expertise. CT, MRI combined with MRCP, ERCP and PTC are also widely used to evaluate obstructive jaundice. Jung et al[30] compared the CT features of HCC invading bile ducts with those of intraductal papillary cholangiocarcinoma, and found that the presence of parenchymal mass is the distinct difference between them. Since no parenchymal mass was detectable on cross-sectional images in our patients, we searched for other signs leading to the diagnosis. After analyzing the intrabiliary lesions on comprehensive images with surgical correlation, we found that the following features may be helpful in the diagnosis of this special type of IHCC.

First, the tumor thrombi are typically intraluminal polypoid lesions with irregular or smooth surface depending on the presence of necrosis. Lesions can be either small or larger. Small lesions are localized in 1 or 2 ducts while large lesions can form “biliary duct casts” and extend inferiorly. Because of rapid growth of the tumor with no apparent fibrosis of the duct wall, the ducts can often be expanded into a fusiform shape at the site of lesion. Cup-shaped filling defects can also be observed in dilated ducts around the lesion on cholangiographic images due to the expanded growth pattern of the lesion.

Second, the tumor thrombi are hypervascular. It is well known that HCC is a hypervascular tumor. Detection of vascularity in bile duct thrombi can reliably rule out the diagnosis of bile duct stones, and differentially diagnose between HCC and cholangiocarcinoma. The bile duct thrombi with the characteristic early enhancement pattern on dual-phase contrast-enhanced CT[30] or dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI[28] are important to differentiate HCC from cholangiocarcinoma. The results of this study support this finding. The hypervascularity of bile duct tumor thrombi was confirmed during surgery in this study. It was reported that color Doppler sonography can also effectively detect tumor vascularity of bile duct HCC thrombi[31].

Third, intraluminal fragments or blood clots may present. Because the tumor thrombi are loose, fragile and prone to necrosis, detachment of parts of the lesions and hemorrhage may frequently occur, and those that are relatively large can lead to free thrombi in the ducts. CT can demonstrate irregular or sludge-like lesions in the ducts with no enhancement. MRI and MRCP may be even superior over CT in demonstrating such lesions[28]. Hemorrhagic lesions or blood clots have a high signal on T1WI, and a low signal on T2WI. Debris in bile appears as sludge in bile ducts and gallbladder.

Fourth, no apparent circular thickening of the duct walls or constriction of the ducts is present. Cholangiocarcinoma is often associated with the thickening of bile duct walls, often leading to constriction of nearby ducts. No apparent thickening of the duct walls, especially no circular thickening of the walls, was observed in our patients, and ducts were compacted rather than constricted or narrowed due to the tumor.

Fifth, no portal vein thrombus is present. It might be due to the relatively early stage of the disease in our patients, and it is critical for differentiating it from diffuse-type HCC.

Sixth, cirrhosis of the background liver may support the diagnosis. A relatively high percentage of cirrhosis was observed on preoperative images and during surgery in our patients. “Downstream duct dilatation”, a sign standing for the dilatated bile duct below the level of intraluminal nodule, has been described by Jung et al[30] in patients with intraductal cholangiocarcinoma, which is thought to be related to mucin produced by the tumor. However, “downstream duct dilatation” was also present in 2 out of 6 patients in our case study, which was contributed to the obstruction by blood clots or fragments in the common bile ducts.

The reasons why HCC is present as intrabile duct tumor thrombi without detectable primary hepatic tumor are as follows. The tumor may originate from cancerization of ectopic hepatocytes in the bile duct wall[17], or the primary tumor is just too small to be identified, or the tumor located at the origin of or close to the intrahepatic duct grows intraluminally and stretchs inferiorly. Although no primary hepatic tumor was demonstrated on preoperative imaging or palpated during operation in our patients, the resected tissues revealed small hepatic tumors in 2 patients. Moreover, since deeply seated small hepatic tumor is hard to palpate during intraoperative exploration, especially in patients with marked cirrhosis, it is hard to rule out the potentiality of small primary intrahepatic HCC in the other 4 patients who did not undergo partial hepatic resection. So, it is recommended that intraoperative ultrasonography (IOUS) should be performed to find the potential intrahepatic tumor or to determine the resection level before the operator decides to perform the resection.

If this disease is suspected, it is still important to look for more sensitive techniques such as CT during arterial portography (CTAP) and superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO)-enhanced MRI to find possible primary tumors. CTAP is generally accepted as the most sensitive technique to detect small HCC, but it is only performed for selected patients due to its invasiveness. SPIO-enhanced MRI has emerged as another effective technique to detect small HCC, but its value in evaluating bile duct tumor has not yet fully investigated. Unless the clinicians or the radiologists take HCC into consideration, these techniques can be first adopted in the diagnosis of obstructive jaundice. Thus, our study may help the clinicians and radiologists to consider this disease before such techniques are applied.

There are some limitations in our study. First, it is a retrospective analysis of a limited number of cases. Second, although dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI is used as a conventional technique for the diagnosis of HCC in our hospital, it has not been routinely performed for the evaluation of obstructive jaundice. Third, contrast studies with other types of HCC or other tumors with intraluminal growth are not available due to the limited number of cases. Further study is needed to verify the diagnostic value of the features listed.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) thrombus in the bile duct is a rare cause of obstructive jaundice. Although it is rarely encountered, its correct diagnosis, especially differentiating it from other causes of biliary obstruction such as cholangiocarcinoma, is very important. Usually, the presence of primary intrahepatic tumors is the key to its diagnosis. However, since few cases of HCC thrombi in the bile duct with no detectable intrahepatic mass have been reported, its diagnosis is even difficult.

Six patients with this rare disease were reported. Their clinical and imaging data were retrospectively analyzed with a review of the literature. Some clinical features and imaging signs that may favor the diagnosis were summarized. The study may be helpful for a better understanding of the disease, especially for its diagnosis.

Little is known about the diagnosis of this rare disease. More accurate diagnosis were introduced in this study by describing their clinical features and imaging signs.

This research may evoke the attention of clinicians to the diagnosis of bile duct hepatocellular carcinoma thrombi without an intrahepatic tumor demonstrated on the diagnostic imaging. If certain clinical features and imaging signs are presented, the diagnosis of the disease can be considered.

The manuscript presents an interesting series of patients with HCC presented as biliary tract obstruction leading to jaundice. The clinical and imaging data help find the features that differentiate this tumor from cholangiocarcinoma.

Peer reviewers: Takashi Kobayashi, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Showa General Hospital, 2-450 Tenjincho, Kodaira, Tokyo 187-8510, Japan; Michael L Schilsky, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine and Surgery, Yale University School of Medicine, 333 Cedar Street, LMP 1080, New Haven, CT 06520, United States

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Lau W, Leung K, Leung TW, Liew CT, Chan MS, Yu SC, Li AK. A logical approach to hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with jaundice. Ann Surg. 1997;225:281-285. |

| 2. | Qin LX, Tang ZY. Hepatocellular carcinoma with obstructive jaundice: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:385-391. |

| 3. | Lai EC, Lau WY. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with obstructive jaundice. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:631-636. |

| 4. | Wang HJ, Kim JH, Kim JH, Kim WH, Kim MW. Hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombi in the bile duct. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2495-2499. |

| 5. | Lin TY, Chen KM, Chen YR, Lin WS, Wang TH, Sung JL. Icteric type hepatoma. Med Chir Dig. 1975;4:267-270. |

| 6. | Huang JF, Wang LY, Lin ZY, Chen SC, Hsieh MY, Chuang WL, Yu MY, Lu SN, Wang JH, Yeung KW. Incidence and clinical outcome of icteric type hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:190-195. |

| 7. | Huang GT, Sheu JC, Lee HS, Lai MY, Wang TH, Chen DS. Icteric type hepatocellular carcinoma: revisited 20 years later. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:53-56. |

| 8. | Yeh CN, Jan YY, Lee WC, Chen MF. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with obstructive jaundice due to biliary tumor thrombi. World J Surg. 2004;28:471-475. |

| 9. | Peng BG, Liang LJ, Li SQ, Zhou F, Hua YP, Luo SM. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor thrombi. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3966-3969. |

| 10. | Peng SY, Wang JW, Liu YB, Cai XJ, Xu B, Deng GL, Li HJ. Hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct thrombi: analysis of surgical treatment. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:801-804. |

| 11. | Qin LX, Ma ZC, Wu ZQ, Fan J, Zhou XD, Sun HC, Ye QH, Wang L, Tang ZY. Diagnosis and surgical treatments of hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombosis in bile duct: experience of 34 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1397-1401. |

| 12. | Badve SS, Saxena R, Wagholikar UL. Intraductal hepatocellular carcinoma with normal liver--case report. Indian J Cancer. 1991;28:165-167. |

| 13. | Buckmaster MJ, Schwartz RW, Carnahan GE, Strodel WE. Hepatocellular carcinoma embolus to the common hepatic duct with no detectable primary hepatic tumor. Am Surg. 1994;60:699-702. |

| 14. | Cho HG, Chung JP, Lee KS, Chon CY, Kang JK, Park IS, Kim KW, Chi HS, Kim H. Extrahepatic bile duct hepatocellular carcinoma without primary hepatic parenchymal lesions--a case report. Korean J Intern Med. 1996;11:169-174. |

| 15. | Kashiwazaki M, Nakamori S, Makino T, Omura Y, Yasui M, Ikenaga M, Miyazaki M, Hirao M, Takami K, Fujitani K. [An icteric type hepatocellular carcinoma with no detectable tumor in the liver but with an intrabile duct recurrent tumor]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2007;34:2099-2101. |

| 16. | Makino T, Nakamori S, Kashiwazaki M, Masuda N, Ikenaga M, Hirao M, Fujitani K, Mishima H, Sawamura T, Takeda M. An icteric type hepatocellular carcinoma with no detectable tumor in the liver: report of a case. Surg Today. 2006;36:633-637. |

| 17. | Tsushimi T, Enoki T, Harada E, Orita M, Noshima S, Masuda M, Hamano K. Ectopic hepatocellular carcinoma arising in the bile duct. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:266-268. |

| 18. | Jan YY, Chen MF, Chen TJ. Long term survival after obstruction of the common bile duct by ductal hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:771-774. |

| 19. | Peng SY, Wang JW, Liu YB, Cai XJ, Deng GL, Xu B, Li HJ. Surgical intervention for obstructive jaundice due to biliary tumor thrombus in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2004;28:43-46. |

| 20. | Shiomi M, Kamiya J, Nagino M, Uesaka K, Sano T, Hayakawa N, Kanai M, Yamamoto H, Nimura Y. Hepatocellular carcinoma with biliary tumor thrombi: aggressive operative approach after appropriate preoperative management. Surgery. 2001;129:692-698. |

| 21. | Kojiro M, Kawabata K, Kawano Y, Shirai F, Takemoto N, Nakashima T. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as intrabile duct tumor growth: a clinicopathologic study of 24 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:2144-2147. |

| 22. | Snarska J, Szajda SD, Puchalski Z, Szmitkowski M, Chabielska E, Kaminski F, Zwierz P, Zwierz K. Usefulness of examination of some tumor markers in diagnostics of liver cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:271-274. |

| 23. | Mann DV, Edwards R, Ho S, Lau WY, Glazer G. Elevated tumour marker CA19-9: clinical interpretation and influence of obstructive jaundice. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:474-479. |

| 24. | Park SJ, Han JK, Kim TK, Choi BI. Three-dimensional spiral CT cholangiography with minimum intensity projection in patients with suspected obstructive biliary disease: comparison with percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:281-286. |

| 25. | Yeh TS, Jan YY, Tseng JH, Chiu CT, Chen TC, Hwang TL, Chen MF. Malignant perihilar biliary obstruction: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographic findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:432-440. |

| 26. | Lau WY, Leow CK, Leung KL, Leung TW, Chan M, Yu SC. Cholangiographic features in the diagnosis and management of obstructive icteric type hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB Surg. 2000;11:299-306. |

| 27. | Kirk JM, Skipper D, Joseph AE, Knee G, Grundy A. Intraluminal bile duct hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Radiol. 1994;49:886-888. |

| 28. | Tseng JH, Hung CF, Ng KK, Wan YL, Yeh TS, Chiu CT. Icteric-type hepatoma: magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance cholangiographic features. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:171-177. |

| 29. | Tamada K, Isoda N, Wada S, Tomiyama T, Ohashi A, Satoh Y, Ido K, Sugano K. Intraductal ultrasonography for hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombi in the bile duct: comparison with polypoid cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:801-805. |

| 30. | Jung AY, Lee JM, Choi SH, Kim SH, Lee JY, Kim SW, Han JK, Choi BI. CT features of an intraductal polypoid mass: Differentiation between hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor invasion and intraductal papillary cholangiocarcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:173-181. |

| 31. | Wang JH, Chen TM, Tung HD, Lee CM, Changchien CS, Lu SN. Color Doppler sonography of bile duct tumor thrombi in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:767-772; quiz 773-774. |